1 Development of African American Studies at the University of Florida (1969-2020) by Patricia Hilliard-Nunn

This chapter was completed posthumously as a tribute to Dr. Patricia Hilliard-Nunn (1963-2020) by Dr. Jacob U. Gordon.

Abstract: The growth of Black Studies, sometimes called Africana Studies and African American Studies, at colleges and universities in the United States was a national movement fueled by the students, faculty, administrators, and citizens in local communities. During the 1960s, the nation was polarized by struggles for voting rights, economic justice, and equality. Citizens protested against police violence, wars, employment discrimination, and other things via sit-ins, strikes, boycotts, marches, and other acts of resistance meant to transform the nation for the better. Desegregation efforts led to an increase in Black students at the University of Florida (UF). This included a nine-year legal battle by Virgil D. Hawkins to enter UF, George Starke being the first black person to enter UF, and W. George Allen, becoming the first black person to graduate from UF. Against the background of local, national, and international activism and struggle, UF’s African America Studies Program was founded in 1969. This chapter critically examines the people, issues and processes that intersected to initiate and run the program. It outlines the trajectory of the challenges and successes that have underpinned the program during 50 years of existence.

The history of Black Studies, often referred to as Afro-American Studies, African American Studies, Africana Studies, African-centered Scholarship, is a product of several historical factors in American Life and Thought. The Black Studies Movement in the 1960s engaged Americans from diverse backgrounds: different age groups, race and color, gender, and educational levels. (Gordon and Rosser, 1974). The movement has been characterized by some scholars as a convergence of two movements: (1) the Anti-Vietnam War Movement and (2) the Black Power Movement (Joseph, 2003); (Small, 2009); and (Early, 2018). Notwithstanding the predictions of the death of Black Studies by some pessimists, Black Studies or African American Studies emerged as a multi-disciplinary academic field, primarily devoted to the study of the history, culture, and politics of peoples of African descent in the Americas. It should be noted here that the field has been defined in different ways, linking the field to the African Diaspora. The field includes scholars of African American, Caribbean Studies; African Studies; Afro-European Literature; history; politics; geography; religion; as well as those from disciplines such as sociology, psychology, anthropology, cultural studies, linguistics, archeology, economics, education, law, race relations, and other disciplines in the humanities and the social sciences (Rojas, 2010); (Rogers, 2012); (Biondi, 2014). And increasingly, the trend in African American Studies is the partnership with academic units in the STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) area (Gordon and Acheampong, 2016).

The birth, growth, and perseverance of African American Studies at the University of Florida (UF) resulted from a collective effort on the part of students, faculty, staff, administrators, and the community at large. For over 50 years, the program has exposed thousands of students to the themes, histories, and theories that encompass the many dynamic aspects of the Black experience. An Afro-American Studies Program, modeled after existing Area Studies Programs, was proposed by a Faculty Committee in the College of Arts and Sciences at UF in 1969 (Hinnant, 1969). It enrolled its first students during the fall of 1970 at the appointment of the first Director of the program, Dr. Ronald C. Foreman. In 1971, the program awarded its first certificate to qualified students. It began offering a minor area of concentration in 2006; a major degree in African American Studies was approved in 2013. The first B.A. degree was awarded in the Spring of 2014.

Founded in the spirit of the struggle that shaped early African American Studies programs and departments across the country, the program is indebted to the men and women who were among the first to enter UF and lay the foundation for those who would follow. The University of Florida opened in Gainesville, Florida in 1906. White women were permitted to enter the University of Florida in 1924. In 1949, Rose Boyd, Virgil D. Hawkins, William T. Lewis, Benjamin F. Finley, and Oliver R. Maxes sought entry to UF Professional and Graduate Schools but were ultimately rejected. From its founding in 1906 until 1958, UF either ignored or denied entry to Black people who applied for admission (McCarthy, 2003).

Although the others dropped out for various reasons, Hawkins waged a legal battle to gain entry to the College of Law. During his battle, the Supreme Court handed down its verdict in Brown v. the Board of Education, which legally ended the segregation of public schools in 1954. This decision ultimately led to the law in 1964 that ended segregation in all public facilities. The Supreme Court of the United States directed Florida courts to allow Hawkins to enter the law school. The Florida Supreme Court, however (including then Justice Stephen C. O’Connell who would later serve as president of UF), resisted the order. Hawkins continued to pursue his efforts to enter UF until 1958, when he agreed to give up his legal battle if UF desegregated its graduate and professional schools. That year, George Starke entered the law school and became the first Black student to enter UF. In 1959, Daphne Duval Williams would become the first Black woman to attend the university. W. George Allen entered the College of Law in 1960 and graduated in 1962; he was the first Black person to graduate. In 1963, seven Black undergraduates, including Stephan P. Mickle, entered UF. Mickle would be the first Black person to earn an undergraduate degree in 1965 and the second Black person to graduate from the law school in 1970.

The desegregation of UF took place during the Civil Rights Movement, a time when greater numbers of Black students were gaining access to predominantly white institutions (PWIs). Once on campus, Black students urged their institutions to infuse the African American experience in the curriculum and to increase the numbers of Black students, staff, and faculty. The April 1968 assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was one of many critical events that increased student activism and intensified their efforts to make the academic mission of their universities more inclusive. They were joined in their efforts by like-minded faculty, staff, and administrators who saw the importance of making the academy more egalitarian and responsive to student concerns. The first Black Studies Department in the nation was founded at San Francisco State University in the Fall of 1968. Working through the Afro American Students’ Association in 1966, it would later be renamed the Black Student Union (BSU). Among other things, the Black students at UF organized to facilitate the establishment of Afro American Studies (later, African American Studies) at UF in 1970 and to make their vision of a well-rounded, quality education a reality.

It should be noted, however, that Afro American Studies, Black Studies, or African-centered Studies has its origin in movements that precede the movements for Black Studies in the 1960s. Popularly regarded as the “Father of Black History,” Dr. Carter G. Woodson (1875-1950) established the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, now the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH), in 1915. ASALH’s official mission was and continues to be “to promote, research, preserve, interpret, and disseminate information about Black Life, History, and Culture to the global community.” In 1926, Dr. Woodson launched the celebration of “Negro History Week,” the precursor of Black History Month (Scott, 2011). The Association published three scholarly journals: The Journal of African American History (formerly The Journal of Negro History) founded in 1916; The Black History Bulletin (formerly The Negro History Bulletin) founded in 1937; and Fire!!!: The Multimedia Journal of Black Studies, launched in February 2011. Dr. Woodson wrote many historical works including his seminal work in 1933, The Miseducation of the Negro. Dr. Woodson was the second African American, after Dr. W.E. B. DuBois, to receive a doctorate (Ph.D.) from Harvard University.

The students who played a role in the development of African American Studies at UF included: Samuel Taylor (the President of the Black Student Union in 1970 who would become the first Black Student Government President in 1972), David E. Horne (a graduate student in African Studies and Instructor at Santa Fe College in African American History), and two other undergraduate students, Emerson Thompson and Larry Jordan.

Some of the UF administrators who were instrumental in establishing the African American Studies Program were: Dr. Manning J. Dauer, Chairman, Social Sciences Division; Dr. Harry H. Sisler, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences; and Dr. Harold Stahmer, Associate Dean, College of Arts and Sciences. The faculty who assisted in the earliest development of the program included: Dr. Hunt Davis, Jr. (History), Dr. Seldon Henry (History), Dr. Steve Conroy (Social Sciences), Dr. James Morrison (Political Science), and Dr. Augustus M. Burns (Social Sciences).

On August 15, 1971, the Black Student Union (BSU) convened and made the following demands (Sachs & McKinnon, 1971):

1. A commitment on the part of the University to recruit and admit 500 Black students out of the quota of 2,800 freshmen and a continuance of the critical year freshman program.

2. Establishment of a department of Minority Affairs under the direction of a full Vice President, and the immediate elevation of Mr. Roy Mitchell to this Vice Presidency.

3. Hire a Black administrator in Academic Affairs with the advice and recommendation of department of Minority Affairs to coordinate the recruitment of Black faculty.

4. The hiring of a Black assistant manager in personnel.

5. Intensification of recruitment and hiring of Black faculty so as to reflect the ratio of Black students admitted under the proposal in number 1.

6. The fair and equal treatments of our Black brothers and sisters, who are employed by the University.

Thus far, even though we have pleaded, begged, and worked diligently with the administration, our cries have been ignored. This University has consistently denied us these basic needs we deem necessary. We are the voice of the Black student, the Black worker, and the entire Black community. And to our full participation as students, employees, and citizens of this state, these needs must be met.

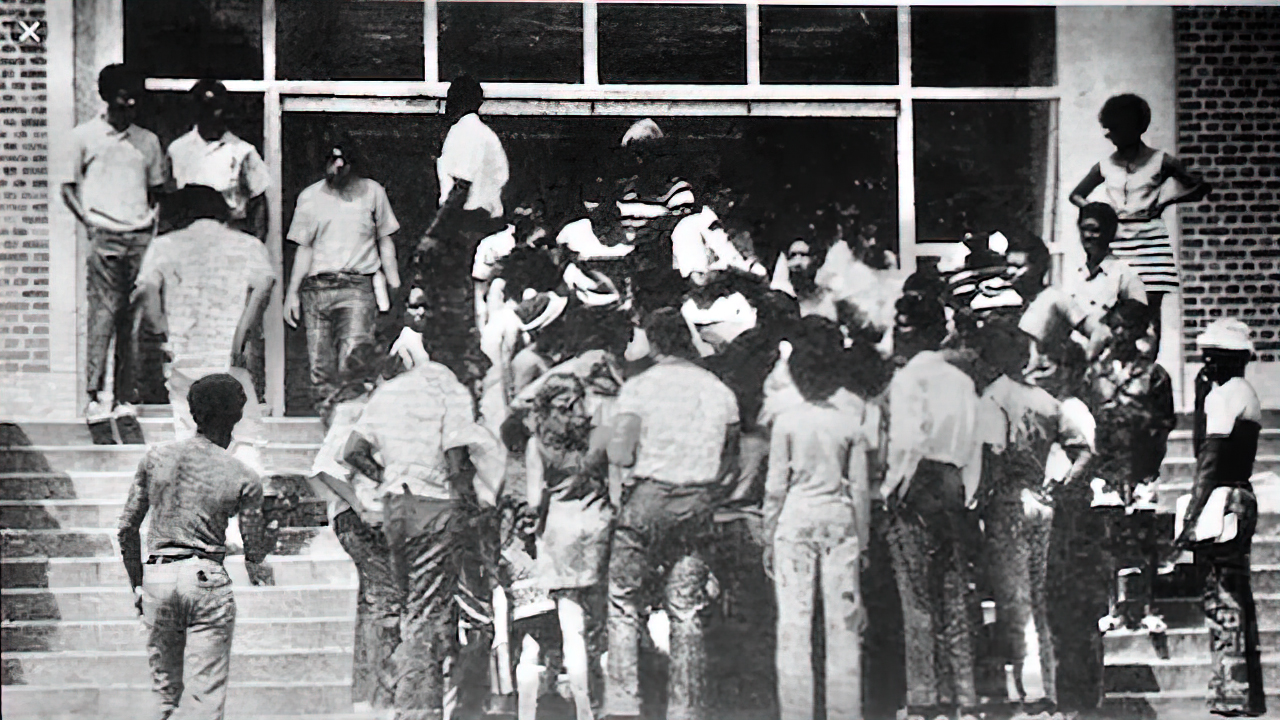

The day-long series of events on April 15, 1971, came to be known as Black Thursday (Figure 1.2); more than 60 Black students were arrested during the demonstrations.

Four important milestones were achieved during the 50th Anniversary of African American Studies at UF celebrations (Figures 1.3 and 1.4): (1) installation and dedication of a historical marker on the campus, acknowledging the significance of African American Studies Program to the mission of the University of Florida; (2) the commitment of the University to transition the program into a Ph.D.-granting academic department in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences; (3) the renovation of new office space in Turlington Hall to accommodate African American Studies faculty and staff; and (4) the national search and appointment of a new Director, Dr. David A. Canton, and the hiring of four new tenure-track faculty members during the following academic year.

African American Studies at UF continues to evolve and grow. The number of students currently working towards earning degrees in AAS is almost one hundred. The program continues its mission of promoting academic excellence and service. Students, faculty, staff, affiliates, and administrators are honored to celebrate 50 years as we look forward to continued growth and development.

Directors of the African American Studies Program, 1970 to the Present

- Ronald C. Foreman, 1970-2000. Ph.D. in Mass Communications, University of Illinois

- Darryl M. Scott, 2000-2003. Ph.D. in History, Stanford University

- Marilyn M. Thomas-Houston, Interim Director 2003-2004. Ph.D. in Cultural Anthropology, New York University

- Terry Mills, 2004-2006. Ph.D. in Sociology, University of Southern California

- Faye V. Harrison, 2006-2010. Ph.D. in Anthropology, Stanford University

- Stephanie Y. Evans, 2010-2011. Ph.D. in African American Studies, University of Massachusetts-Amherst

- Sharon Wright Austin, 2011-2019. Ph.D. in Political Science, The University of Tennessee, Knoxville

- James Essegbey, Interim Director 2019-2020. Ph.D. in Languages and Linguistics, Leiden University

- David A. Canton, 2020-Present. Ph.D. in History, Temple University

Current Core Faculty and Staff

- Vincent Adejumo, Senior Lecturer. Ph.D. in Political Science, University of Florida

- Manoucheka Celeste, Associate Professor. Ph.D. in Communications and Gender Studies, University of Washington

- Ashley Preston, Lecturer. Ph.D. in History, Howard University

- Rik Stevenson, Visiting Assistant Professor. Ph.D. in African American Studies, Michigan State University

- Yesenia Jarrett, Administrative Specialist I

Affiliate Faculty

- Stephanie Birch, Librarian in African American Studies, Smathers Libraries. M.L.S. in Library Science, University of Illinois-Urban Champaign; M.A. in History, University of Illinois-Springfield

- Clarence Gravlee, Associate Professor, Department of Anthropology. Ph.D. in Anthropology, University of Florida

- Paul Ortiz, Professor of History and Director, Samuel Proctor Oral History Program. Ph.D. in History, Duke University

- Leah Rosenberg, Associate Professor, Department of English. Ph.D. in Literature, Cornell University

- Samuel Stafford, Lecturer, Department of Political Science and Adjunct Professor, College of Law. J.D., Duke University

- Delia D. Steverson, Assistant Professor, Department of English. Ph.D. in Literature, University of Alabama

Advisory Committee

- Stephanie Birch, African American Studies Librarian, Smathers Libraries

- Steven Butler, Executive/Artistic Director, Actors Warehouse

- Kandice Simmons, President, Black Graduate Student Organization

- Eric Godet, President/CEO, Greater Gainesville Chamber of Commerce

- Jacob U’Mofe Gordon, Professor Emeritus, University of Kansas; President, Alachua County African and African American Historical Society, Inc.

- Robyn Hankerson, President, Association of Black Alumni

- Agnes Ngoma Leslie, Master Lecturer and Outreach Director, Center for African Studies

- Barbara McDade Gordon, Professor Emerita, Geography and African Studies

- Paul Ortiz, Professor of History and Director, Samuel Proctor Oral History Program

- Diamond Overstreet, Co-Founder, Duo Studios

- Jon Rehm, Curriculum Specialist Social Studies K-12, Alachua County School District

- E. Stanley Richardson, Alachua County Poet Laureate, Founder/Director of Art Speaks

- Eric Segal, Director of Education, The Harn Museum of Art

- Harry B. Shaw, Professor Emeritus, English

- Carl Simeon, Director, Black Affairs/Institute of Black Culture

- Lindsay Symphany, President, Black Student Union

African American Studies – Timeline

1906: UF opens in Gainesville, Florida and admits only while males.

1924: The State of Florida rules that white women can attend UF.

1949: Virgil Hawkins, Rose Boyd, Benjamin Finley, William Lewis, and Oliver Maxey apply to graduate and professional schools at UF. They are all rejected.

1954: Brown vs. Board of Education. U.S. Supreme Court orders public schools desegregated.

1957: The U.S. Supreme Court rules that Virgil Hawkins should be accepted at UF. The Florida Supreme Court, which included future UF president Justice Stephen C. O’Connell, ignored the decision.

1958: Virgil Hawkins agrees to end his legal battle to enter the College of Law after UF agrees to desegregate graduate and professional schools.

1958: George H. Starke is the first Black person to attend UF. He entered the College of Law.

1959: Daphne Duval Williams is the first Black woman to attend UF. She entered the College of Education.

1960: W. George Allen enters the UF College of Law.

1962: W. George Allen is the first Black person to graduate from UF.

1963: Seven Black undergraduate students enter UF.

1965: Stephan Mickle (who becomes Federal Judge Mickle) is the first Black undergraduate to graduate from UF.

1968: Visiting Professor Spencer Boyer is the first Black faculty member at UF Law School, teaching in the College of Law. He and his family are forced to leave Gainesville abruptly after receiving violent threats.

1968: Ron Coleman is the first Black scholarship athlete after earning a track and field scholarship.

1969: Roy Mitchell (now Dr. Roy I. Mitchell) becomes the first Black administrator at UF when he is hired as the Director of Minority Affairs.

1969: Leonard George and Willie B. Jackson are the first two Black football players at UF.

1969: Afro-American Studies Program is established. Dr. Selden Henry is the Advisor/Head.

1970: The Black Student Union (BSU) is formally recognized as a UF student organization.

1970: Dr. Thomas Miller Jenkins II, the former Dean of FAMU’s Law School, is appointed to the UF College of Law faculty.

1970: Dr. Ronald C. Foreman begins as the first director of what was then labeled Afro American Studies. He, Dr. Carleton G. Davis (Food Resource Economics), and Dr. Elwyn Adams (Music) are the first three tenure-track Black faculty members at UF.

1971: After unsuccessful attempts to address concerns about the campus climate at UF, students hold a sit-in at Tigert Hall and present a list of 10 demands to the administration. That day, April 15, is known as “Black Thursday.”

1971: In April, Roy I. Mitchell submits his letter of resignation (effective June 1) as head of Minority Affairs in the aftermath of Black Thursday. The resignation is accepted immediately.

1971: The first certificate in African American Studies is awarded.

1972: The Institute of Black Culture opens.

1972: Samuel Taylor is elected the first Black Student Government President.

1973: Cynthia Mays is elected as the first Black Miss Homecoming.

1974-75: James M. Webster, Jr. becomes the first Black Assistant Football Coach at UF.

1986: Pamela Bingham becomes the first Black woman elected as UF Student Government President.

1991: The Black Awareness Movement. Students take over the Student Government offices because of complaints about how Black History Month was funded.

1994: The first “Umoja Graduation Celebration” for Black Student at UF is held.

2001: Virgil D. Hawkins is awarded a UF law degree posthumously.

2006: The African American Studies Program begins offering a Minor.

2013: The African American Studies Bachelor of Arts degree is approved.

2014: The first three students majoring in African American Studies graduate.

2019: The African American Studies Program turns 50!

2020: Dr. James Essegbey is appointed as Interim AASP Director.

2020: African American Studies moves into new offices in 1012 Turlington Hall.

2020: Dr. David A. Canton is appointed as the Director of AASP.

Chapter 1 Study Questions

- To what extent did the national movements for Black Studies on college/university campuses impact the development of African American Studies at the University of Florida?

- Briefly discuss some of the major African American Studies milestones at the University of Florida.

- What are some of the major contributions of African American Studies in higher education?

References

Asante, M.K. (2005). Encyclopedia of Black Studies. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Bennett, L. Jr. (2005). “Carter G. Woodson, Father of Black History.” United States Department of State archived from the original, retrieved September 10, 2020.

Biondi, M. (2014). The Black Revolution on Campus. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Early, G. (2018). African and African American Studies Frontrunners. Washington Magazine, digital.

Gordon, J.U. & Rosser, J.M. (1974). The Black Studies Debate. Lawrence: The University of Kansas.

Gordon, J.U. and Owoahene-Acheampong, S. (2016). Trends in African Studies. New York: Nova Science Publishers.

Hinnant, L. “Credit coming soon for UF Black Studies” (1969, August 1) The Florida Alligator, 1A.

Joseph, P. E. (2003). “Dashikis and Democracy: Black Studies, Student Activism, and the Black Power Movement.” The Journal of African American History, 88(2), 182-203. https://doi.org/10.2307/3559065

McCarthy, K.M. (2003). African Americans at the University of Florida, UF Sesquicentennial Committee, Naples, FL.

Rogers, I.H. (2012). The Black Campus Movement: Black Students and the Radical Reconstitution of Higher Education, 1965-1972. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Rojas, F. (2010). From Black Power to Black Studies: How a Radical Social Movement Became an Academic Discipline. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

Sachs, R. & McKinnon, K. “67 blacks jailed: Disturbance flares on campus” (1971, April 16) The Florida Alligator, 1A.

Scott, D.M. (2011). The History of Black History Month. Archived July 23, 2011, as the Wayback Machine on ASALH website.

Small, M.L. (2009). [Review of the book From Black Power to Black Studies: How a Radical Social Movement Became an Academic Discipline, by F. Rojas]. Journal of Black Studies, 39(6). 990-992. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021934708321242

White, D.E. (2010). From Desegregation to Integration: Race, Football, and “Dixie” at the University of Florida, Florida Historical Quarterly, 88(4), 469-496. Retrieved March 11, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/29765122

Video Productions

Samuel Proctor Oral History Program (SPOPH) (2018, April 3) A Tale of Two Houses: A Dialogue on Black and Latinx History at UF, Public Program featuring Dr. David L. Horne. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dXnXVgmhaDM&t=1834s

Samuel Proctor Oral History Program (2019) From Segregation to Black Lives Matter: The Opening of the Joel Buchanan Archive of Oral History at the University of Florida, Public Program. http://ufl.to/tu

African American Studies Ronald C. Foreman Symposium at the University of Florida (2020) Looking Back and Moving Forward: African American Studies at the University of Florida Turns 50. Public Program. http://ufl.to/tt