8 Barbara Jordan for Congress

It was fortunate for Barbara that congressional redistricting occurred when it did, enabling her to plan to run for election to the U.S. House of Representatives rather than for re-election to the Texas Senate. Under the redistricting plan, Houston state senate districts had also been altered, and with the way the new district lines were drawn, it would be very difficult for a Black to win in Barbara’s old 11th District. It had been redrawn to include approximately the same percentage of Blacks (38 percent), but the whites it now included were not the blue-collar, working-class whites of the old district; they were middle-class whites, who shared fewer common interests with Blacks. They would be less likely to vote for a Black candidate. Also, it now included areas already represented by incumbent white Senator Chet Brooks, who would be a difficult opponent for a Black Senate hopeful. Testifying before a court hearing on the redistricting in a suit brought by State Representative Curtis Graves, Barbara said even she probably couldn’t win re-election to her old seat. Of course, she wasn’t planning on seeking re-election, a situation that Graves pointed out. “I am fully cognizant of the fact that this district was carved out for Senator Barbara Jordan and that she already has begun a campaign,” Graves had said back in the summer of 1971.

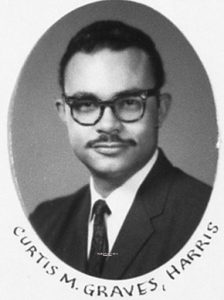

At that time Graves also decided to seek election to the U.S. Congress from the newly created 18th District. Two of the very few Black officeholders in Texas running against each other for the same office was not in the best interest of Black politics in Texas. It might split the Black and liberal vote in the district. But in politics, as in most other areas of life, it’s everyone for him or herself. When the Harris County Democratic Party, a liberal organization, met to make its endorsements in late March 1972, it avoided a split in its ranks by giving Jordan and Graves dual endorsement. Both Jordan and Graves lived in Houston. Both espoused liberal Democratic causes. Both had been elected to the Texas legislature in the same year and shared the distinction of being among the first three Blacks to serve in the legislature since Reconstruction.

Beyond these similarities the two had little in common. Graves was a native of New Orleans and had attended Xavier University there before moving to Houston. He had received a degree in business administration from Texas Southern University and worked as a public relations consultant before being elected to the Texas House in 1966. In 1969, he was an unsuccessful candidate for mayor of Houston. Married and the father of three children, Graves had an outgoing personality. Early in his first session in the Texas House the pageboys had named him representative of the week. His wardrobe included a fire-engine red vest.

Barbara was quieter, more subdued. She commanded respect more than outright friendship; it took time for people to get to know her well. And although she didn’t object to a fire-engine red vest, she herself dressed conservatively.

Graves was emotional and not ashamed of it. “I cried the morning I was sworn in,” he said. “I realized it wasn’t a dream anymore. It was reality. I realized a whole segment of history was over, and a new segment was beginning.”

Barbara kept her emotions under tight rein. Only once, back in 1967 when she’d been named outstanding freshman senator, had she nearly broken down. The quiver in her usually strong voice had occasioned comment in the newspapers, for it was a rare occurrence. Charlotte Phalen, a Houston Post reporter, once related to Molly Ivans, then a Washington Post reporter, an anecdote that revealed the extent of Barbara’s self-control: Phalen had invited Barbara to her home for a game of poker and Barbara had accepted, although because of her strict Baptist upbringing she was hardly accustomed to playing cards. “You know how most people who’ve never handled a deck before will drop the cards all over and fumble around? Not Barbara. She gripped each card firmly and carefully set it down in front of each player. Not one of those slippery little things was going to get out of her control.”

Curtis Graves was highly outspoken. In the spring of 1967, after he had sat in session in the Texas legislature for some two months, Graves was asked what he thought of his fellow Black representative, Joseph Lockridge. “He’s just sprayed Black,” Graves said. “He doesn’t think Black.” By contrast, when asked how he felt about Graves, Lockridge had said simply, “I have made his acquaintance. He is competent.” In August 1971, when he expressed his intention to run for the 18th Congressional District seat, Graves had this to say about Barbara: “Senator Jordan has demonstrated a blind loyalty to the Democratic Party machine…. [She] has seldom involved herself in anything controversial, let alone anything controversial concerning the Black community.”

Barbara Jordan always spoke in measured words, appealing to reason, stating the facts. In response to Graves’s criticism that August she had stated simply: “The representation of Black people does not have as a necessary prerequisite involving oneself in controversial issues. In my judgment Black people want representatives who can get things done for them. I am quite willing to offer myself to the Black community on the basis of my record of performance.”

With two such distinct personalities opposing each other, the race for the Democratic primary election in May promised to be a lively one.

Graves formally announced his candidacy early in February, and in a speech at T.S.U. he made clear that his campaign would be largely based on his contention that Barbara had “sold out” her constituents: “I feel now, more strongly than ever, that the congressman from this new district must be someone who owes his allegiance to the people who live in the district, not to the corrupt politicians who have brought our state into national shame and ridicule,” Graves said.

“If you are looking for someone who goes along to get along, one who plays politics with your lives, one who is long speaking, but short on delivering services, then don’t vote for Curtis Graves.”

Throughout the campaign Graves would stress the “sellout” issue; and the press, always interested in controversy, printed his charges, giving him good publicity. But Barbara got more press coverage. Although some of it was not directly related to the campaign, it was most helpful to her candidacy.

It was customary periodically throughout the year for the Senate to elect a president pro tempore to serve as assistant to the lieutenant governor, the presiding officer of the Senate. Whoever occupied that position automatically became third in line of succession to the governorship; it was the highest office the Senate could give. With the convening of a special session of the Senate in late March, the election of a new president pro tern was one of the first orders of business. The Senate usually rotated the job on a seniority basis, but this time there was not one but eight senators next in line—Barbara and seven others had all come to the Senate in the same year. But it was no contest. Sixteen senators rose to give seconding speeches to her nomination, and she was elected unanimously. Their remarks indicated just how highly her colleagues regarded her.

“It is a high compliment, and I speak for all of us when I say we are proud of you,” said A. M. Aiken, senior senator.

Senator Roy D. Harrington expressed amazement at the amount of work she had been able to accomplish: “She has been able to get more legislation through than most of us.”

Senator Ralph M. Hall, a conservative, and often her enemy on legislative matters, praised her, too: “She must command our respect for her work for those who have no lobby.”

And Chet Brooks called her “one of the finest human beings I have ever known.”

A beaming Barbara Jordan rose to be sworn in and delivered a brief acceptance speech: “When I came here January 10, 1967, we were all strangers. Now, on March 28, 1972, I am enjoying the friendship and fellowship of this body. Nothing can happen in my lifetime that can match the feeling I have for my service in the Texas Senate, and nothing that can happen to me in the future will be greater than receiving this high honor right now.”

By mid-April, the primary candidates were campaigning hard. The streets of the 18th Congressional District were papered with posters—VOTE FOR CURTIS GRAVES—and few automobile bumpers escaped being adorned with campaign stickers. Barbara’s campaign material was of a higher quality than Graves’s. The print on his leaflets faded quickly and wasn’t properly aligned. Being a public relations consultant, he was disturbed by the unprofessional look of his material, but there was nothing he could do about it. He didn’t have the money Barbara had. She was getting $5 in campaign contributions for every $1 he received.

Barbara’s campaign was being financed by whites, Graves charged. Downtown whites were supporting her in “an open attempt to buy the first Black congressman from the South.” According to Graves, the money Barbara was receiving was being contributed in return for Barbara’s having helped redraw the state Senate district lines in a way that would prevent another Black from being elected to the Senate for the next ten years. Barbara replied that when the list of contributors to her campaign was made public, as required by law, “it will clearly show there is no faction or select group financing my bid for election.”

As to Graves’s charges that she had deliberately redrawn the Senate district lines to exclude Black representation in the legislature, Barbara stated, “The drafting of the Senate redistricting bill was done by a legislative redistricting board. I had nothing to do with that board.”

Sometimes it seemed to Barbara that she was spending half her campaign time and money responding to Graves. She had enough to do without constantly restating her answers. Campaigning was exhausting activity, although Barbara never seemed to show her tiredness. On a typical day, for example, she was at her law office at 8 A.M., opening her mail and answering telephone calls. By 9, she was at her first campaign stop, a union headquarters, shaking hands, making a brief speech, answering questions. She concentrated on her record in the Texas Senate—the number of bills she had introduced and the number that had been passed, the ways in which she had helped poor and working people. She contrasted her record in the Senate with that of Graves in the House—only one of the bills he had introduced had been passed. Sometimes she couldn’t resist an obvious pun and would refer to “the Graves we are going to dig on May 6,” but as a general rule, she refrained from making personal remarks about her opponent.

On to her campaign headquarters to see how the supply of leaflets and bumper stickers was holding out, then lunch and another campaign stop, this time at a vocational high school. “The society which scorns plumbing because plumbing is a humble activity and tolerates shoddiness in philosophy because it is an exalted activity will have neither good plumbing nor good philosophy,” she told the students. “Neither its pipes nor its theories will hold water.”

Pleased with her reception at the school and with her speech, she hummed as she drove hack to her headquarters. She enjoys music, and when she isn’t listening to it on the radio, she hums to herself. After an hour or so directing operations at her headquarters, she got back into her car and set off for another appearance, this time at a housing development. Traffic was heavy. She let a Cadillac move in front of her.

“Lady,” she said, “my name is Barbara Jordan and I am running for Congress. Don’t forget that I let you in.”

She visited a supermarket; she spoke to a group of beauticians at a church; she appeared at a meeting of Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers. She shook hands but rarely back-slapped. She smiled at babies but didn’t kiss them.

It was late in the evening when she returned home.

While eating the supper her mother had kept hot in the oven for her, she told her parents briefly what her day had been like. Then, exhausted from the day’s activities, she got a few hours’ sleep. Late in April, a reporter asked her how she managed such a hectic schedule. She smiled. “Some nights you crawl into bed and you think, ‘What is it I’m really doing?'”

On Saturday, May 6, a large number of Democratic voters turned out at the polls, and by mid-afternoon early reports showed Barbara had a commanding lead over Curtis Graves.

“They’re stealing the election from me,” Graves complained, “but I can’t prove it. I can’t get any poll watchers.”

Barbara did not respond to these new charges of Graves’s.

By evening, it was time for Barbara’s victory speech. Final results would show that she had won 80 percent of the vote and had carried Black, Mexican-American, and white sections of the 18th District.

“Back in December when I entered this race, I promised to represent all the people of the 18th District, Black, white, brown, young and old, rich and poor,” she told her cheering supporters. “Nothing has happened in this campaign to change that resolve. Instead, I have received support and votes from all those groups. It is widespread support that has enabled me to win today, and I’m deeply grateful for it.”

She did not say much about Graves except that she considered their contest unfortunate because “Houston’s Black community can’t afford to lose any leaders.” Later, though, both she and Graves would come to feel that perhaps their contest had contributed to the political education of Houston’s Black voters. “It has brought a maturation of the Black voter,” she said. “He has to look at the person and say, ‘What can he or she do for me?’ Whites have been doing it for years, but the Black voter is just now changing his voting pattern from habit to the issues.

“When I first ran for the legislature in 1962, the Black voter didn’t know what the legislature was supposed to do,” she continued. “With my election to the Senate and Curtis’s election to the House came a new awareness. Now you couldn’t find a Black in Houston who doesn’t know something about the legislative process.”

The celebrations at her campaign headquarters lasted far into the night, and by the time she got to bed, it was 5:30 Sunday morning. At 8:30 she was up and slogging through the rain to Good Hope Missionary Baptist Church, where, after services, the church ladies honored her with a tea that lasted four hours.

Back home the phone rang. Barbara sighed and picked up the receiver.

“Hate to be a nuisance, but I—” said the voice on the other end.

Barbara cut the caller short. “Yes,” she said, “I am very tired.”

The worst was over, however. Opposition from her Republican opponent in the November election would be token at best. She was already talking about how she would act in Congress.

“I’ll go there with as much in-depth knowledge as possible of the issues that concern people and move into that body in a way most effective to get things done. I want to get in motion and attend to the concerns of the people of the 18th District.”

It would be nine months before she took her seat in Congress. She still had her Texas Senate term to finish. And before she assumed the job of congresswoman, she had another office to hold—that of “Governor for a Day.”