3 Big Hopes…

The first thing Barbara Jordan did upon returning to Houston was to study for the Texas bar exam. Because Texas had some of the strangest and most complicated laws of any state, passing the exam was not easy. Even those students who studied at Texas law schools, and thus concentrated on Texas law, found the exam hard to pass. It was not uncommon for candidates for the Texas bar to take the exam two or three times before passing it. Barbara passed the exam the first time.

Licensed now to practice law in her home state, Barbara did not have the money to open an office of her own. In fact she barely had enough money to have a stack of business cards printed with ATTORNEY AT LAW. She began her practice on her parents’ dining room table. It was hard to attract clients at first, but gradually friends of the family began to come to her and to recommend her, in turn, to their friends. She handled a variety of problems—real estate sales, business matters, domestic relations. In divorce cases her first interest was to explore the possibilities of reconciliation. Her favorite cases were adoptions. “The happiness that goes with adopting a baby or a child brings joy to everyone who had a part in helping to make it possible,” she said.

At the same time Barbara was taking steps to establish herself within the Houston legal profession. She joined the American Bar Association and the Houston Lawyers Association, and in 1960, she got involved in politics. It was a presidential election year. Former Vice-President Richard M. Nixon was seeking the office vacated by two-term President Dwight D. Eisenhower. His Democratic opponent was John F. Kennedy. Across the country Blacks were restive, aware of the gradual growth of the movement for equal rights. John Kennedy promised to support the fight for those rights. Just at the time when Blacks were feeling the possibility of asserting themselves, a presidential candidate came along who seemed worth asserting themselves for. Black Texans had an additional reason for backing the Democratic slate —John Kennedy’s vice-presidential running mate was Lyndon Baines Johnson, U.S. senator from Texas, a man who, despite his geographical origins, was as firmly committed to the civil rights cause as Kennedy.

Like most women in politics, Barbara Jordan began her political career stuffing envelopes, running mimeograph machines, and doing all the other menial tasks traditionally regarded by male politicians as “women’s work.” She did her work and did not complain, waiting for an opportunity to prove her effectiveness.

That opportunity came soon. Barbara recalls: “One night we went to a church to enlist Negro voters and the woman who was supposed to speak didn’t show up. I volunteered to speak in her place and right after that they took me off the stamp licking and addressing.”

Late in the summer, the word came down from the Democratic organization that the Black vote could carry the election for Kennedy and Johnson, and it was up to Black Democrats to get out that vote. Barbara was given directorship of the “Get Out the Vote” drive in Houston’s Black community. It was the first such drive, and she had little advice to rely on regarding how to go about it. She certainly didn’t have much experience herself. But she’d always had organizational ability, and she put it to work at this time. She launched a one-person-per-block precinct drive, finding Blacks who were willing to drum up votes on their own blocks and getting out lists of eligible voters and leaflets to help them in their campaign. She attacked the problem just as she had attacked her studies at school. She worked until midnight or one or two o’clock in the morning, as long as it took to get the job done. “Whatever people may believe is needed in our country, they should believe strongly enough to work for it,” she says.

Kennedy and Johnson won the election by a slim margin, but they won just the same. Looking at the vote tallies from the precincts in which she had conducted her voting drive, Barbara felt pride that she had been instrumental in the Democratic victory. Just as important, she had proved her abilities to the Harris County Democratic Party organization.

Within the next year and a half, Barbara’s position and influence in Houston grew. By 1962, she had strengthened her law practice and accumulated enough money to open her own office at 4100 Lyons Avenue, not far from her home. A second-floor walk-up above a print shop, whose sign read KNOCK & HOLLER, her office was nevertheless her own. It was shabby at first, but over the years she would install pine paneling, a red carpet, and air conditioning. Among her first additions to the decor were framed color photographs of John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. They would remain on her walls long after both men were no longer in the White House.

By early 1962, Barbara had been elected president of the all-Black Houston Lawyers Association, despite the fact that she was the sole woman member and only twenty-six years old. The reasoning behind her election by her fellow members was simple: “Get Barbara to do it, and you know it’ll be done right,” as one of the association’s leaders said. Similar respect for her abilities led to her appointment as second vice-chairman of the Harris County Democrats and a board member of the Houston Council on Human Relations.

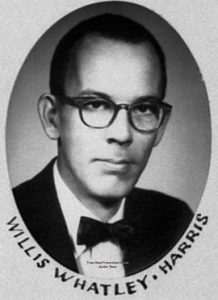

Armed with these credentials and a self-assurance remarkable for the average twenty-six-year-old but expected in Barbara Jordan, she announced her candidacy for the Democratic nomination for state representative, Position 10, on February 3, 1962. That no other Black woman before her had ever campaigned for the nomination did not daunt her. That no other Black had served in the Texas House since Reconstruction concerned her even less. She was bright, she was a hard worker, she had a clear platform, and she felt she would do a better job than those against whom she was running in the May 5th Democratic primary: a former assistant district attorney named Willis Whatley—her major opponent—and a Church of Christ minister, Jim Shock. She was so confident that she even, in a sense, ran against her own party: She announced she was running as an independent Democrat “who feels strong enough to resist pressures which most certainly will be brought to bear on candidates supported by the slate.”

She had almost no money. In fact, she had borrowed the $500 filing fee to become a candidate for the seat. The drawing of the county political lines was also against her. Unlike counties in many other states, counties in Texas were not divided into districts. Even in a populous area like Harris County, which included Houston, representatives were elected county-wide, which meant that all of the over one million eligible voters voted for each representative. Under this system, some parts of the country had no local representatives, while other parts had too many. Political experts gave her no chance of winning, but still Barbara Jordan was confident: “In my political naïveté I believed that I was more articulate than my opponent and sensitive to people’s needs and aspirations. These qualities, I felt, would help me overcome the odds against my election to the Texas House.”

During the next three months, Barbara campaigned for the Democratic nomination, speaking before women’s groups, Y.W.C.A. meetings, United Fund agencies, anywhere that she could be heard; and everywhere she was heard, she moved her audience with her commanding presence and her no-nonsense presentation of the issues.

But she was not really prepared for the personal questions she received. Suddenly her family, her school career, her personal likes and dislikes, were of interest. Barbara did not like such prying. She would give her qualifications readily, but her private life was another matter. She would speak at length only about the books she had read:

“I found that A Shade of Difference by Alan Drury had so much of an aura of reality that it became fascinating reading. Failsafe, another best seller, is similarly an enjoyable, if disturbing, story.

“I’d also like to mention Nobody Knows My Name, the collection of essays by James Baldwin. This expression of raw and naked tenderness by a Negro sort of laid my soul bare. I could see this man struggling with himself, and I could feel with him in what he was trying to do.”

Barbara Jordan based her campaign on issues. The most important one, in her eyes, was that of welfare reform:

“It’s so unfair to see the really handicapped people starving while so many others who are able to make their own way are getting a free ride on the state’s welfare rolls. There are thousands of persons in this state who just can’t feed and clothe themselves because of old age or physical handicap. I’ll do everything I can in the legislature to see that these people are taken care of. At the same time, I’ll see what can be done about striking from our welfare rolls the people who are just trying to get out of work. If this group were stricken from the rolls, the ones who go hungry and hopeless could be taken care of.”

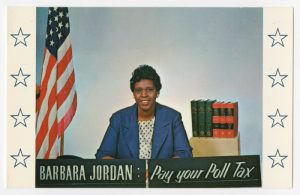

Other aims in her campaign included abolition of the poll tax, which she felt discriminated against eligible but poor voters; an increase in the state’s minimum-wage law; revision of the sales tax law; and equal property rights for women. She addressed herself to no particular group, and indeed, felt no allegiance to any particular group. Her allegiance was to her vision of a better Texas:

“My hope as a member of the legislature is to have a part in making Texas a better state for all of her ten million people. We have the oil, the land, the trees, the manpower, the brains, the good will, to improve the level of living for all. We can make better use of what we have—not by taking anything away from anyone, but by creating more, so that the share of each is greater.”

In her commanding voice she stated these aims over and over, but she never had an opportunity to debate Whatley. “I rarely saw my opponent in person,” she recalls, “but I was confronted by his face on many billboards and on the television screen. He was obviously well financed.”

Considerable money was needed for a county-wide campaign. To reach all the people, a candidate needed billboards and television coverage. Even with a dedicated volunteer organization Barbara could not hope to reach through speeches and leaflets and doorbell ringing as many people as could her opponent. She recalls, with the air of someone who has learned an important political lesson: “I felt that if politicians were believable and pressed the flesh [shook hands] to the maximum extent possible, the people would overlook race, sex, and poverty and elect me. They did not.”

Barbara received 46,000 votes; Willis Whatley got 65,000. She tried to rationalize her defeat: “I figured anybody who could get 46,000 people to vote for them for any office should keep on trying,” she said ten years later. But back in 1962 her rationalizations had a hollow ring, even to her own ears.

There was some consolation. While she was unable to take the active political role she desired, and while she resented the conditions that prevented Blacks in general from participating equally in the political process, she was nevertheless pleased with the national administration. John F. Kennedy had said, in speaking of social and racial conditions in the United States, “We can do more,” and he was providing examples of that belief, encouraging Martin Luther King, Jr., in his fight for equal rights for Blacks, inaugurating programs to help poor people of all races, and introducing into Congress bills to benefit minorities and the poor. One of his most “visible” acts had been to support Black Congressman Adam Clayton Powell, ranking majority member of the House Education and Labor Committee, for the chairmanship of that committee, against considerable opposition even from members of his and Powell’s Democratic Party. During the 1962 campaign Barbara had publicly supported Kennedy-type programs in Texas. In November 1963, the president was scheduled to visit Texas, and she was pleased about the recognition he would bring to the cause of Black and poor people in the state.

On November 22, 1963, John F. Kennedy was killed by an assassin’s bullet as he rode with Texas Governor John Connally in an open car through the streets of Dallas. The tragedy stunned the country. The young president had inspired many people and given them the sort of hope and belief in their country that they had not had before. Especially bitter for Texans, particularly Blacks, was the fact that John Kennedy had been killed in their state.

Vice President Lyndon Johnson took the oath of office as president on Air Force One, en route from Dallas to Washington, while the body of the slain president rested in the rear. Johnson was well-liked among Texas Blacks, and they were disturbed that he would assume the presidency under the shadow of his predecessor’s death. Later, once the initial period of grief was over, there was speculation about what Johnson would do as president. Would he continue the programs and changes begun under Kennedy? All anyone could do was wait and see.

Meanwhile Barbara continued her law practice, maintained her active roles in the Houston Lawyers Association and the Harris County Democratic organization, and increased her schedule of speaking engagements. She intended to run for the Texas House again in 1964, and saw the advantages in starting early, in gaining through time and hard work what well-financed campaigns could attain for their candidates through billboard and television advertising.

On January 25, 1964, she once again announced her candidacy for the Texas legislature, Position 10, the position held by Willis Whatley, who had defeated her two years before.

“It is urgent that the legislature become more responsive to the needs of the people of Texas,” she said in her announcement speech. “Skilled lobbyists speak for every kind of interest except that of the average citizen. The real need is to make it possible for all Texans to become more productive. Education, job training, and the elimination of the burden of discrimination will help.”

The specific issues in her platform were the same as they had been in 1962. Why? Because nothing had been done about them in the two years since she had last run.

This time Barbara was a more experienced candidate. She had built up a large volunteer organization and she held open houses at her campaign headquarters to attract more workers. She realized that as a Black female candidate she was not even taken seriously by many voters, and certainly not by the political “establishment,” but she thought that this time she could persuade some of the purveyors of public opinion to remain neutral.

“I went to the newspaper publishers and acknowledged their probable difficulty in supporting me editorially but urged them not to support my opponent—just to take a chance on the people making the best choice,” Barbara recalls. “One of the major papers in Houston made no endorsement; the other endorsed my opponent.”

In the election Barbara received 66,000 votes, but Willis Whatley still received more. She had lost again. Her supporters reminded her that the decision of one major Houston newspaper to remain neutral was something of a victory. They also pointed out that a respectable percentage of the 20,000 more votes she had received this time had come from traditionally white, conservative areas. But that did not make Barbara feel much better about her two losses in a row.

Up in New York Shirley Chisholm had won election to the State Assembly, the second Black woman to be elected to that body. Elsewhere in the North and the East, Blacks were beginning to win elective offices on local and state levels. The movement would reach the South and West eventually, Barbara’s supporters assured her. That didn’t make her feel any better either. She was, as she remembers, “dispirited.”

“I considered abandoning the dream of a political career in Texas and moving to some section of the country where a Black woman candidate was less likely to be considered a novelty. I didn’t want to do this. I am a Texan; my roots are in Texas. To leave would be a cop-out.”