1 Early Years

It was hot outside on that late July afternoon in Washington, D.C., and inside the chambers of the House Judiciary Committee the climate was almost subtropical. The television-camera strobe lights were hot, and the myriad video equipment radiated additional heat, as did the bodies of the people who packed the room. Congressional aides and spectators vied for space and view with members of the media—reporters from television, radio, and newspapers; newspaper photographers; television camera and audio men. On a raised, two-tiered platform at the front of the room sat the thirty-eight men and women of the House Judiciary Committee, trying to conduct the business at hand in a solemn, no-nonsense manner. The task was extremely difficult. Despite the intention of most of the members to conduct their historic business as decorously as possible, this was no ordinary committee hearing. The House Judiciary Committee hearings on the impeachment of President Richard M. Nixon were a media event.

As seen through the eyes of the television cameras, each member of the House Judiciary Committee took on a particular personality, like actors in a dramatic series. The American public could understand the party, geographic, racial, and sexual lines that were drawn within the committee. Republicans and southern Democrats seemed to be sympathetic to the president. Northern Democrats, Blacks, and women seemed to be against him. But within these groupings each member was a unique personality, and many seemed “made” for television: William L. Hungate, Democrat of Missouri, with his folksy wisdom and humor; strident Charles Sandman, Republican of New Jersey; earnest Tom Railsback, Republican of Illinois.

Anyone watching the proceedings closely, day in and day out, learned what to expect from most of these people. They would state and restate their opinions, each in his or her own particular way, some quietly, some harshly. Each would invoke the Constitution, for it was a constitutional question they were addressing in deciding whether or not to recommend impeachment, and each would claim that the Constitution supported his or her opinion. After a time the word Constitution became almost meaningless. But on July 25, 1974, when “the gentlelady from Texas,” as Chairman Peter Rodino called Congresswoman Barbara Jordan, faced the television cameras and began to speak, the concepts of the Constitution took on a new meaning, and in this era of media events, she became a media personality.

“‘We, the people,'” she began in her resonant voice, “it is a very eloquent beginning. But when the Constitution of the United States was completed on the 17th of September in 1787, I was not included in that ‘We, the people.’ I felt for many years that somehow George Washington and Alexander Hamilton just left me out by mistake.”

There was no humor in that beginning of her speech. Barbara Jordan is Black. And her statement that for many years she thought she’d been “just left out by mistake” rang true. Most American parents stress to their children the importance of being Americans; but after a time, Black and other minority children learn that while they are American-born, they are not the same sort of American as white children. It’s very hard for children to accept being different through no fault of their own. “Maybe someone just forgot us,” they decide.

Barbara Charline Jordan was born at a time and in a place where only children could entertain such an idea. Black adults in Houston, Texas, in the 1930s understood that they were second-class Americans and had learned to live with that knowledge. They lived and worked knowing that they were limited not only by social customs but by actual laws. They had to use “colored” restrooms and water fountains, which were never as plentiful or accessible as those reserved for whites. When they rode on public buses they had to sit in the back, and if the bus was crowded they were expected to give up their seats to whites. They lived in segregated housing and had to send their children to segregated schools. In theory, they possessed the right to vote to change these conditions. But poll taxes and literacy tests and outright intimidation by whites prevented most of them from going to the polls to change the discriminatory laws. Their influence was so slight that they could not even get decent lighting for their streets. In 1930, Blacks made up 22 percent of the population of Houston, a city that existed as two separate societies connected only by economic necessity. The three main Black areas—San Felipe near downtown, the southeast and the northeast parts of the city—seemed to exist only to serve the white areas, for the majority of the Black people who lived in these areas earned whatever meager incomes they did earn in service to whites—as maids and nannies, as chauffeurs and yardmen and laundry workers. These Blacks had to go to the white areas to work, but otherwise they avoided placing themselves in situations that were degrading to them, and almost every situation in which they found themselves in the white areas was degrading. If they went downtown to shop, they were served in the back of the store; if they were hungry, they had to walk blocks to find a cafeteria or restaurant that would serve them. The white sections were filled with perils for Blacks, who could be stopped on any pretext by a policeman or accused of wrongdoing if they dared look a white person in the eye. So the Blacks stayed out of the white areas as much as possible and kept to themselves in their segregated enclaves. There they might be poor and without legal or political influence, but at least they did not have to worry about walking on the “wrong” side of the street or looking in the “wrong” direction. And they kept their children in these enclaves as long as possible, to shield them from the brutal realities of the world outside. As long as they were so shielded, the Black children of Houston had little idea of the larger world. It was possible to go for days without seeing a single white person other than a policeman. As Barbara Jordan recalls, “We were all Black and we were all poor and we were all right there in one place. For us, the larger community didn’t exist.”

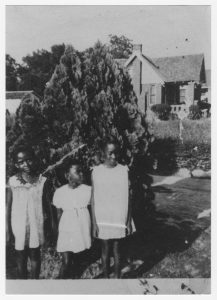

Barbara was born on February 21, 1936, the youngest of Benjamin and Arlyne Jordan’s three children, all of whom were girls. Her father was a Baptist minister, with churches in the rural areas of Thompsons and Kendleton, and thus the Jordan family enjoyed a position of some respect in the Houston Black community. The Black church was one of the few areas where Blacks controlled their own activities relatively free from white supervision; it was the hub of organization, cooperation, management, finance, and self-government in the Black neighborhood. The Black minister, therefore, was a combination social, moral, and political leader, and a major force in the community. Still, Black churchgoers in rural parishes were not financially able to support their minister. To supplement his scanty income, Benjamin Jordan also worked as a warehouse clerk. The family lived in a modest frame house at 4910 Campbell Street surrounded by a small, well-kept green lawn. Inside, the furnishings were simple but adequate, just like those in the other houses on the street. “We were poor,” says Barbara Jordan, “but so was everyone around us, so we didn’t notice it. We were never hungry and we always had a place to stay.”

Family life for the Jordans revolved around two basic areas—religion and music. God was ever-present, and though they did not have much money, they were secure in the belief that they were cared for and loved. Music, too, was ever-present. Both Benjamin and Arlyne Jordan sang and played musical instruments, and they encouraged the musical abilities of their daughters. Barbara’s favorite instrument was the guitar.

Music was the chief source of pleasure in the Jordan family. Card playing, for example, was strictly forbidden, for Mr. Jordan considered it a sinful activity. “We were raised in the strictest Baptist sense,” says Barbara, “no drinking, smoking, or dancing.” The girls were encouraged to read—all were familiar with the Bible at a very young age. Books on history were favored, and no novels or comic books were allowed. Mr. Jordan was a strict disciplinarian, and much of the great self-control that Barbara Jordan exhibits is due to his influence. “I always had to keep the lid on, no matter how angry I got,” she says. “It did not have to do with his being a minister; it was my respect for him as a person. I had great respect. It was unthinkable to have a hot exchange of words with him, for me or my mother or any of us. So one does develop quite a bit of control that way. I suppose the kids now would say that was not good.”

While he was very strict, her father was also very supportive. His great loves, Barbara has said, were his family, his faith, and his language, in that order. As a grown man, Benjamin Jordan was highly aware of the inequities that Black people suffered in a predominantly white, segregated society, but to hear him speak to his young daughters, one would never have known it. They were told early and often that they could be anything they wanted to be as long as they were willing to work for it. And he told them, and showed them by example, that one’s sense of dignity and self-worth is not derived from others but from oneself.

Today, when she speaks to groups of young people, Barbara echoes her father’s sentiments: “There is no obstacle in the path of young people who are poor or members of minority groups that hard work and thorough preparation cannot cure. Do not call for Black power or green power. Call for brain power.”

Benjamin Jordan demanded a considerable amount of brain power from his daughters. Intelligence is not subject to either discrimination or segregation: “No man can take away your brain,” he would tell his children. And Benjamin Jordan expected not only intelligent thinking but also intelligent articulation of those thoughts. He loved the English language—the power of the precise word and its precise pronunciation. It was from her father that Barbara learned the speaking ability that has become her hallmark.

Barbara grew to be very much like her father, and in later years it was hard for the two to recall who was stricter with her—her father or Barbara herself. Barbara recalls, “I would bring home five A’s and one B, and my father would say, ‘Why do you have a B?'” But Benjamin Jordan used to remember report card time differently: “She was unhappy if she made less than a straight A average in school.” Barbara was a competitive youngster, but her concern for grades was not just a matter of outdoing her classmates; it was a matter of living up to her own rigorous standards.

Partially because of her father’s supportiveness, but mostly because of something in herself, Barbara needed little outside reinforcement of her sense of self-worth. Serious, controlled, mature beyond her years, she had a natural dignity. Her father once said, “I realized when she was a little girl that Barbara was one of the rare ones.”

As she grew older, Barbara Jordan began to understand that the world she knew—the Black community, segregated Black schools—was a very small, insular one and that beyond it was a large and not particularly friendly white world. She still did not have to deal with it personally very often, but she began to learn about it from books and from hearing people talk. In school she learned about slavery and studied the history of the United States. In the 1940s and early 1950s, when she was in grade school and high school, Black Americans accommodated themselves to the discrimination and segregation they suffered from the larger white society. Black children heard little militant rhetoric, were not taught to feel bitterness about the hypocrisy of a so-called democracy in which a sizable minority group enjoyed few rights. Yet a bright and perceptive youngster like Barbara Jordan could not help noticing that the United States Constitution had been written and adopted without a single mention of slavery, bondage, or Negro. That fact troubled her. “Maybe,” she sadly concluded, “they just forgot.”

By the time she entered high school, Barbara had acquired a greater understanding of race relations in the United States. She had felt the sting of racist remarks and the sense of how unfair it was to be judged by the color of her skin rather than by her intelligence or her personality or her character. She had listened to her parents and other Black adults talk about the lack of opportunities for Black people and about the long list of civil and legal rights they did not have. She had come to realize that the framers of the Constitution had not forgotten her at all, that they had deliberately avoided mentioning Black people. Why this was she could not be sure, but she suspected that the men who had written the document had recognized the hypocrisy of stating that “all men are created equal” and then including in that document mention of the very people who were not treated as equal. The framers of the laws in the southern United States in the mid-twentieth century were not so sensitive. Their laws clearly indicated their belief that only whites were created equal. Barbara knew that as a Black person the odds were against her. Further, she was a woman and not even possessed of the qualities that women have traditionally used to their advantage. As she told her homeroom teacher in high school, “I am big and Black and fat and ugly, and I will never have a man problem.” She had often heard adults say that a Black person had to be twice as good as a white person in order to succeed. And yet all that daunted her not at all; she intended to succeed, and in a big way. “I always wanted to be something unusual,” she says. “I never wanted to be run-of-the-mill. For a while I thought about being a pharmacist, but then I thought, whoever heard of an outstanding pharmacist?”

Her two older sisters, Bennie and Rose Mary, wanted to be music teachers. That was a realistic goal for young Black women in Texas. But Barbara was more ambitious. She wanted to be something more. She just couldn’t figure out what.

Avidly she read biographies of successful people; she particularly liked reading the life stories of presidents. There were many Black people whose lives could serve as models—Black people who had become famous or successful despite the strictures of white society. There was Frederick Douglass, who had been born in slavery and had escaped to the North to play a major role in the abolition movement. There was Booker T. Washington, who had been the chief spokesman for Black people early in the twentieth century and who had founded Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. W. E. B. DuBois had graduated from Harvard University at a time when only a miniscule proportion of the Black population even went to college, and had gone on to be a major Black writer and intellectual. There were women too. Like Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman had been born in slavery and had escaped to the North. Her part in the fight against slavery had been different from Douglass’s, but no less important. She became one of the most famous “conductors” on the Underground Railroad, risking her own safety over and over to lead hundreds of slaves to the North and freedom. A half century later, Mary McLeod Bethune also served as a role model for young Black girls. As a young woman she had founded a school for Black girls in Florida, which later became Bethune-Cookman College. During the administration of Franklin Delano Roosevelt she had been the president’s trusted friend and adviser, and she had founded the National Council of Negro Women.

The high school Barbara attended was named for another famous Black woman, Phillis Wheatley. Born in Africa, Phillis Wheatley was kidnapped at the age of eight and brought to the United States as a slave. She wrote her first poem when she was fourteen, in perfect English. A few years later she became the first Black, the first slave, and the second woman ever to publish a book of poetry in America.

Reading about these people reinforced in Barbara’s mind what her father had taught her. If she was willing to work hard for it, she could be almost anything, and one day during her sophomore year in high school she decided what she wanted to be.

Each year the school held a Career Day. Blacks from various professions were invited to come and speak to the students. By explaining what their careers were like, what talents or aptitudes were needed, they tried to help the students make their own career decisions. In retrospect, the very idea of a Career Day for Black high school students in Texas in 1950 seems painfully over-hopeful. Although opportunities were gradually beginning to open up in some fields, career choices for Black youth were severely limited. Most would end up as laborers and domestic workers. Teaching was the only truly open profession. Black doctors were needed, for white doctors often refused to treat Black patients. A career in the armed services was possible, but there were no Black officers. More Blacks were entering the legal profession, and there was a small but growing movement toward establishing equal rights for Blacks in the courts. Because of this situation, the administration at Phillis Wheatley High School had invited Edith Sampson, a Black lawyer from Chicago, to speak to the students.

That a busy woman would travel all the way from Chicago to speak to a group of high school students in Texas attests to her great interest in encouraging Black youth, particularly young Black women, to enter law. Edith Spurlock Sampson knew they needed that encouragement, and she hoped to show them that if she could succeed in the legal profession, then so could they. She had been born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and had attended school in New York and Chicago. She received her Master of Law degree from Loyola University in Chicago, the first woman of any race to receive that degree from the institution. She had begun her law practice in Chicago in 1926, specializing in criminal law and domestic relations, and had served as an assistant referee in Cook County Juvenile Court. In 1947, she had been the first Black woman to be appointed an assistant state’s attorney in Cook County. Just prior to speaking to the students at Phillis Wheatley High School, she was appointed by President Truman as an American alternate delegate to the United Nations. Some years later, she would become Judge Edith Sampson.

Barbara listened intently to this Black woman lawyer from Chicago and scrutinized her closely. Edith Sampson was a large woman, with a pleasant face and an impressive bearing. Her voice was as compelling as her argument—if I can do it, so can you. Barbara could identify with this woman. She could imagine her own large frame attired in a neat tailored suit, imagine the sound of her own already judicious voice commanding the attention of a courtroom or auditorium audience. Edith Sampson was something special. Barbara decided she wanted to be a lawyer.

When Barbara confided her ambition to be a lawyer to her parents, she met mixed reactions. Arlyne Jordan was against the idea, for she did not think it was the right thing for a girl to do. Her two other daughters had pursued careers proper for women. They would marry and lead a secure, Black middle-class existence. Law was a profession for men; she was not sure her youngest daughter could make it as a lawyer.

Hearing her mother’s reaction, Barbara sighed. Like her sisters, Bennie and Rose Mary, she had taken music lessons from a private tutor for years. But though she enjoyed music, she knew a career in it just wasn’t for her. She’d told her parents so.

Benjamin Jordan, on the other hand, was pleased. While he shared his wife’s fears that Barbara had chosen a difficult path for herself, he had no thought of trying to keep her from it. Barbara recalls, “My father said I should do whatever I thought I could.”

In June 1952, Barbara Jordan graduated from Phillis Wheatley High School in the top 5 percent of her class. She was determined to be “something outstanding,” and there was no doubt in her mind that she would be.