10 First Year in Congress

Barbara Jordan was not completely immersed in her studies at Harvard between November 1972 and January 1973. She was busy arranging for the furnishing of her office in the Rayburn House Office Building and finding a place to live. (She invited her mother to come to Washington to live with her, but Mrs. Jordan preferred to remain in Houston.) She was also trying to select a Washington staff and a staff to take care of her business in Houston while she was in Washington. In this, as in most other things, she did an excellent job; her staff was among the most efficient of the congressional staffs around and had been instrumental in helping her build her own reputation for efficiency and preparedness. And finally, she was beginning her drive for membership on the House Committee on the Judiciary. Barbara wanted to be on that committee. When asked why, she said it would complement her legal background and deal in legislation important to the problems of her district (it was a major checkpoint for civil rights legislation). Shortly before the 93rd Congress convened, former President Lyndon B. Johnson telephoned Representative Wilbur D. Mills of Arkansas, then chairman of the powerful House Ways and Means Committee, which made committee assignments for all Democrats, and expressed his hope that Barbara would be appointed to the Judiciary Committee.

The 93rd Congress convened on January 3, 1973. Along with other new legislators Barbara took the oath of office from House Speaker Carl Albert. About one hundred supporters from Texas witnessed the ceremony. They had come on a plane specially chartered for the purpose. After the House session, a reception for Barbara was to be held in a committee room in the Longworth House Office Building.

The first session of the 93rd Congress was not long, but there was some business to conduct. A Speaker of the House had to be elected. Representative John Conyers of Michigan, head of the Congressional Black Caucus, made a token bid for the job, but Carl Albert from Oklahoma had seniority and was the favorite. Barbara voted for Albert.

Barbara also received a job, one that usually goes to a freshman member, that of secretary of the Texas delegation. The vote was unanimous with the exception of her own. She voted for herself as chairman!

Barbara was late for her party. After the formal session on the House floor she had sought out New Jersey Democrat Peter Rodino. Rodino was slated to be named chairman of the Judiciary Committee, and of course Barbara wanted to put in her bid to be on it. For his part, Rodino wanted to get Barbara on the committee, because he could use her support in his largely Black district in Newark, New Jersey. Traditionally two representatives from Texas sat on the committee, and since one Texas seat was vacant . . . Arriving late at the party given for her, Barbara was cheered when she explained she had been on the floor of the House “working for them.”

Most of the other representatives from Texas were at the party, as well as some representatives from non-southern states. Barbara took charge of introducing her fellow congressmen to the crowd.

“And there’s Representative Burleson,” she said as she stood on the platform and peered over the heads of the crowd, “a charming man I earnestly want to introduce to you. He’s a member of the House Ways and Means Committee and consequently will have a lot to say about my committee assignment.”

The crowd laughed, and so did Burleson. “And she’ll get whatever she wants,” he said to those around him.

A week later, Barbara had her committee assignment. On January 22, 1973, former President Lyndon B. Johnson suffered a fatal heart attack. Aware of the mutual respect and admiration Johnson and Barbara had for each other, a reporter called Barbara that night. The Barbara Jordan who answered the telephone was not in very good control of herself. In a grief-stricken voice, she said, “I think history will record Lyndon Johnson as one of the greatest presidents this country has had.”

Barbara would never forget Lyndon Johnson or what he did for her and for Black people. “Old men straightened their stooped backs because Lyndon Johnson lived,” she once said. “Little children dared to look forward to intellectual achievements because he lived. Black Americans became excited about a future of opportunity, hope, justice, and dignity because Lyndon Johnson lived.

“He was my political mentor and my friend,” she added. “I loved him. And I shall miss him.”

Over the next few months, Barbara missed Lyndon Johnson more and more. President Richard Nixon seemed to be doing his best to undermine the social programs of which the Johnson administration had been so proud. Proposed cutbacks in the new federal budget included money for health, welfare, housing, urban development, sewage treatment plants, and community projects. With two other representatives from the Houston area, Barbara held hearings in Houston to find out just how the cutbacks would affect the people of Houston. What they learned made the legislator resolve to fight the cutbacks wherever possible.

Meanwhile, Barbara was concerned that the government belt-tightening seemed to be hurting most the people who could afford it least. “Why wasn’t Nixon also talking about reducing subsidies?” she asked. She was equally concerned that the senior Democrats in the House seemed to be unwilling, or unable, to stand up to the president. After all, there was a Democratic majority in the Congress. Quietly, Barbara and the other first-term Democratic representatives came together in an informal caucus to act as a catalyst in convincing Congress to resist the will of the White House. In April, after the House failed to override two Nixon vetoes on spending measures, Barbara and another freshman Democrat, Edward Mezvinsky of Iowa, decided to defy the tradition that freshman members are traditionally seen and not heard. “In the ninety days that I’ve been in Congress,” said Barbara, “I find that Congress is having difficulty finding its back and its voice.” She and Mezvinsky decided to ask for four hours’ time on the House floor in mid-April for the freshmen to make their plea. They went to see Speaker of the House Carl Albert to discuss their desire to prod the House into reasserting its authority. Albert seemed compliant. To each point the freshmen raised, he said, “Fine.” But Barbara sensed that he really wasn’t paying much attention to them. Finally, Barbara exploded and told the Speaker that it wasn’t all “fine.” “The inability of the Democratic majority to decide on a course of action and to move on it…has caused a deep sense of depression, not only among freshmen, but among some of the most senior members of Congress,” she said. More serious in Barbara’s mind than the depression of Congress was the imbalance between executive and legislative branches of the government that threatened the most basic parts of the Constitution.

The freshmen’s opportunity to speak came a week later. In the interim, two of the Texas Democratic freshmen pulled out of the program, complaining that the original idea of discussing the budget control problem had “exploded” and the caucus had become labeled as both anti-administration and anti-House Democratic leadership. Undaunted, Barbara remained in the program, and in her remarks on the House floor on April 18 said that the nation faced “one-man rule” on federal spending and “inaction in the Congress.”

“As freshmen members of Congress, we have a unique perspective on this,” she said in her speech. “We are here because the American people voted against monolithic government in the 1972 elections. They clearly wanted some restraint on executive branch power, and they hoped to get it by electing Democrats to Congress while a Republican president maintained control of the White House.”

As freshmen, she said, she and her colleagues didn’t expect to wield a great amount of power in Congress, but “we do not expect powerlessness of Congress as an institution.”

Powerlessness was a frustrating problem for the freshman congressmen in the 93rd Congress. So were the rules, the bureaucracy, the rigamarole, that attended the legislative branch of the U.S. government. The rules were not as arcane as those of the Texas legislature, but the political interests were more complex and more numerous. The Texas legislature had debated issues that concerned Texas; in the Texas Senate, there were only thirty-one voices to be heard. The U.S. House of Representatives was composed of people who represented a much broader political spectrum and made decisions affecting the whole country. And there were so many representatives, each highly aware that they came up for re-election every two years and thus were impelled to produce, even if his or her production was just words. To many freshman congressmen, the situation was strange, frustrating, and sometimes ludicrous, and they were drawn to each other as a consequence of both their powerlessness and their incredulity.

Barbara Jordan and Charles Wilson formed a close relationship that spring. Both were from Texas, and they had served together in the state Senate. Politically they differed at times, but they both shared the same feeling about the process of government in the nation’s capitol. It was pompous, wasteful, and sometimes funny.

“Charles and I never take ourselves seriously, but we both work very hard,” Barbara said that spring. “We get so tickled at the folks who act as if they were in sole control of the ship of state. We can’t resist sticking a pin in such puffery just between the two of us.”

Wilson said of Barbara, “She’s one of the few real people in a profession that is known for its phonies. I have a high regard for her because she is a no-nonsense person who votes compassionately and tries to do for her people. But she doesn’t wear it on her sleeve. She’s not a grandstander.”

Barbara was equally complimentary of Wilson. In the House, the tall, lanky white man and the tall, heavyset Black woman came to be called “the odd couple,” but not derisively.

“They’ve got the right idea,” said a fellow member of the Texas delegation. “They get as much done as the rest of us and yet they’ll probably escape the ulcers bit. You might as well enjoy public service if you can.”

Wilson was one of the Texas freshmen who had declined to participate in the attempt by Barbara and other first-term congressmen to “wake up” the House of Representatives. Barbara told him it was his first real chance to stand up to the president and he had muffed it. He smiled and told her jokingly that he was a tool of the administration.

It is unlikely that the speeches by Barbara and the other freshman Democratic members of the House made any major impact, although they did establish the fact that the freshmen did not intend to be silent, as they were traditionally expected to be. Richard Nixon continued his one-man rule, and during the months that followed, it seemed that he might soon be the one man in his original administration left in the White House. In January, the five Watergate burglars and the two men accused of directing their operations had been brought to trial, and all had been sentenced to prison terms. All had remained silent and declined to take the witness stand in their own defense, which had further aroused the suspicions of many that people in high places had known about the burglary. Judge Sirica, who presided over the case, said publicly that he was “not satisfied” that all the facts had been brought out and he urged a congressional inquiry. Shortly afterward, on February 7, the Senate created a Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities, headed by Senator Ervin. In addition, many members of the press voiced suspicions. Their reports and articles kept the Watergate affair before the American public and maintained pressure on the Nixon administration. Events began to move swiftly as new facts were brought to light. On April 30, John Dean, counsel to the president, was fired, and John Ehrlichman, assistant to the president for domestic affairs, and H. R. Haldeman, chief of staff at the White House, resigned because of their involvement in the Watergate affair. At the same time, Attorney General Richard Kleindienst resigned because of his closeness to the people now under investigation.

This was Barbara’s reaction: “The question remains: Is this enough? Does this really take care of all the wrongdoers? I will reserve my judgment until we see whether this cleans house or not.”

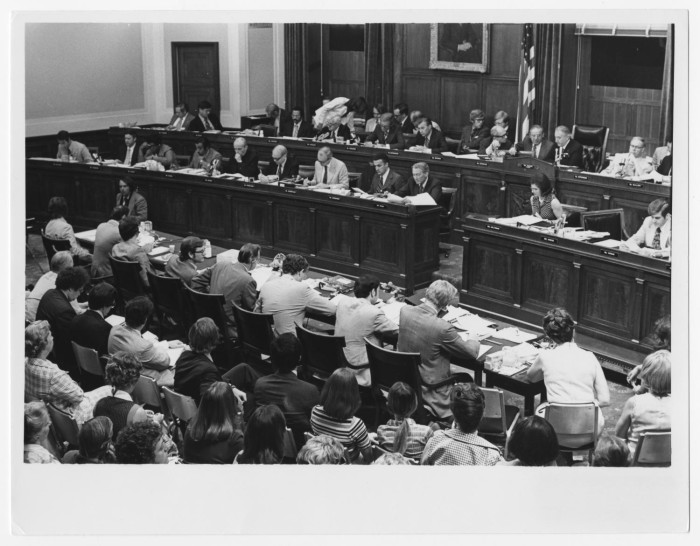

Within a few days it became apparent that the “house” was not “cleaned.” John Dean was busily leaking stories all over Washington about the Watergate scandal and hinting that President Nixon himself had been involved in trying to cover up White House involvement in the burglary. The special Senate committee began its televised hearings on May 17 to investigate the matter, and on May 22, the new attorney general Elliott Richardson appointed Harvard law professor Archibald Cox as special prosecutor to handle an independent investigation.

Much of the credit for uncovering the relationship between the Watergate burglars and the White House belonged to the press, particularly the Washington Post. Barbara Jordan praised the press publicly for doing so. Now, perhaps, Congress would reassert its authority and regain its constitutional powers from the control of the president.

“We have learned that we cannot allow excessive delegation of power to go unchecked,” she said. “Today I am very hopeful that some of the money [frozen by Nixon] for education and health care will be restored by Congress.”

But the Watergate scandal and its repercussions seemed to overshadow all other activity of the legislature. On October 30, 1973, the special prosecutor for Watergate, Archibald Cox, was fired by the president. Cox had been promised complete independence; but after it had become known that Nixon had for years ordered all his office and telephone conversations taped, and Cox had subpoenaed those tapes that he felt were relevant to Watergate, he was fired. As a result, Attorney General Elliot Richardson and his deputy, William Ruckelshaus, resigned.

All of this happened on the same day. The press called the affair “the Saturday Night Massacre.” Barbara told reporters she thought the firing of Cox was “a serious intrusion into the administration of justice.” Of Richardson and his deputy aide she said, “Their resignations remind us that it has become difficult for men of conscience to serve President Nixon. It is a tragedy that we have to constantly remind this president that there are certain principles of justice which are embodied in the traditions and laws of this country.”

In Congress, it was proposed that there should be a special prosecutor truly independent of the president. Nixon had said he would appoint a new special prosecutor, who would have “independence and total cooperation” from the White House, but many members of Congress believed any special prosecutor under direction of the White House could not really be independent. Barbara was one of them. In testimony before the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Criminal Justice she called upon Congress to authorize the U.S. Court of Appeals to appoint a new special prosecutor.

“In a sense we ask too much of this administration,” she said. “When the executive branch is both defendant and prosecutor, we should not expect either dispassionate inquiry or vigorous prosecution.”

She introduced a bill into Congress that would permit federal grand juries to ask district judges to appoint special prosecutors during investigations of officials of the executive branch of government.

Before the bill could be acted upon, Acting Attorney General Bork appointed a new special prosecutor—none other than Leon Jaworski, Houston attorney. Jaworski’s terms for accepting the appointment were stiff. The president could not fire him except for “extraordinary improprieties,” and he must be guaranteed the right to sue in court for presidential tapes and other evidence.

Politics is a small world, thought Barbara upon hearing the news. Now her old friend Leon Jaworski was special prosecutor. She believed he would be a fair and independent one—he would not bow to administration wishes.

Discussion by the House Judiciary Subcommittee about the office of special prosecutor was tabled. There was other serious business to attend to. Early in October, Vice President Spiro Agnew had resigned, pleading nolo contendre (no contest) to charges of Federal income tax evasion. In the House, it was the job of the Judiciary Committee to hold confirmation hearings on the president’s new appointee.

Gerald R. Ford was a Republican from Michigan who was well-liked in Congress. Barbara Jordan agreed that he was a personable man, but that didn’t qualify him for the vice-presidency. In the confirmation hearings she came down hard on his civil rights record. Asked about his stand on civil rights, Ford declared that every American is entitled to equal treatment. “I’ve lived that, I believe that, I insist on that,” he said.

Barbara was not convinced. She recalled that Ford had once said in a speech, “In politics, when the train is moving, you’d better jump on because you don’t get a second chance.”

Would it be fair, she asked, to characterize his voting record on civil rights as “trying to stall the train as long as you can and then jumping on when you know it will keep on going no matter what you do?”

Ford said he disagreed. Barbara fixed one of her famous stares on him. He shifted uncomfortably in his seat.

The questioning of Ford was rugged—so rugged, in fact, that Barbara predicted a Nixon resignation in mid-1974. “It was evident that in the minds of many of the members was the unspoken thought that Mr. Ford would be president and that its job was really confirming the next president of the United States,” she said. Barbara, for one, didn’t believe Ford was qualified.

When the Judiciary Committee voted on his confirmation, hers was one of the eight dissenting votes. Now Ford’s appointment would go to the full House for a vote.

The Judiciary Committee voted on Gerald Ford on December 1, 1973. Three days later Barbara was hospitalized for tests. Lately she had been feeling a numbness in her arms and legs—she obviously had some sort of infection in the nerve endings in her limbs. She had begun feeling the sensation—which was similar to the feeling one gets when one’s foot goes to sleep—on November 29. Doctors at the hospital decided to keep her there for a week.

That meant she would be unable to vote when the full U.S. House of Representatives decided on the confirmation of Gerald Ford as vice president. Her absence bothered her. So far during her first term, she had voted 99 percent of the time, the highest record of voting participation among members of the Texas delegation, and the ninth highest record among members of the entire Congress. Her vote would not have made a difference, however. On Thursday, December 6, Gerald Ford was confirmed by a sizable majority of the House.

On Saturday, December 8, Barbara left the hospital. Doctors there had been unable to discover the cause of the infection. But at least they had ruled out cancer, tumors, and other serious causes. She was back at work on Monday, and her colleagues in Washington seemed pleased that she was. The Senate Ladies (wives of senators), however, were a bit miffed. They had sent her flowers while she was in the hospital, and they had never received a thank you by word or note. Barbara was getting a reputation in Washington for such discourtesies. It wasn’t that she was rude, really —cold was the word most often used.

Late in December, Congress recessed and Barbara had an opportunity to look back on her first months in the U.S. House. She described the experience as not exactly frustrating, but one that had “required tremendous patience on my part at times.” It also required a great deal of work. By the time she reached her southwest Washington apartment at night, she had time only to fix dinner for herself, skim through the legislative business for the next day, and fall into bed. She hadn’t time for the round of cocktail parties for which Washington was famous. Her life was her work.

Yet she was glad she was in Congress and pleased with her performance, although she had necessarily been limited because she was a freshman. She was proud of her 99 percent voting record and of her part in the attempt by freshman Democratic representatives to “wake up” the Congress to President Nixon’s “one-man rule” over federal spending. She was also pleased that the American Conservative Union had rated her voting record on major issues the lowest of the Texas delegation. But she was most pleased with her membership on the House Judiciary Committee, which in the next year seemed certain to consider whether President Nixon would be impeached. Perhaps the most important constitutional question of the century would be decided, and she would be a part of the process.

Hearings on impeachment were sure to be held, and Barbara had become reticent about Nixon since her prediction that he would resign. She was deeply aware of her responsibility under the Constitution that she regarded so highly.

“If I was convinced now that Mr. Nixon is guilty of a crime worthy of impeachment, then I ought to disqualify myself,” she said to anyone who asked. “An impartial investigation demands an open mind and I intend to keep one.”