5 Freshman in the Texas Senate

On Tuesday, January 10, 1967, the capital city of Texas, Austin, found itself inundated with people. Swearing-in day at the state legislature had always brought relatives and well-wishers, but never anything like the crowds that converged on the city on this historic day for Black Texans. For the first time since Reconstruction three Black legislators would sit in the Capitol. They were Representatives Curtis Graves of Houston and Joseph Lockridge of Dallas and Senator Barbara Jordan.

Hundreds of Blacks came to Austin to wish their new representatives well. They arrived in chartered buses and in private cars, some having gotten up at 4 A.M. to make the trip. Some 450 people came from Houston alone. Their two fellow Houstonites were to be sworn in, and one of them would be the first Black in the Texas Senate since 1883.

Student council members from E. O. Smith Junior High School, which Barbara had attended, waited to greet her as she walked into the Capitol. The Metropolitan Senior Citizens Club of Houston sent a delegation. Perhaps these old Black people could appreciate the event the most, because for the greater part of their lives there had been little hope that it could ever happen. “It’s the greatest experience of my life,” said one elderly man. “I stuck my chest out. I’ll never forget this day. You don’t know how hard I’ve worked for this.”

Passing between lines of smiling Black faces, Barbara, wearing a white orchid for the occasion, made her way into the Senate chamber. The gallery was filled with supporters. She looked for and found her mother and father, her sisters, an aunt, an uncle. She recognized other faces, but there were many she did not recognize—ordinary Black people to whom her victory meant practically as much as it did to her. As she entered the chamber, they broke into cheers. “They didn’t know about the rules [against demonstrations],” Barbara later explained. “I looked up at them and covered my lips with my index finger. They became quiet instantly, but continued to communicate their support by simply smiling. Finally I had won the right to represent a portion of the people in Texas.”

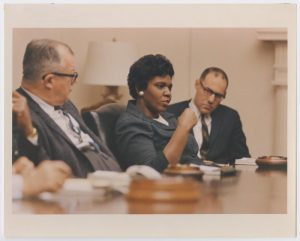

After she had repeated the oath of office in her deep, clear voice, she was welcomed by many colleagues, who hastened over to shake her hand. All white, all male, they provided a starkly contrasting background for the newcomer. “You didn’t have any trouble picking me out down there, did you?” she jokingly asked her uncle later. But as rules and meetings were discussed, she immediately became a part of the assemblage, listening intently to the points raised, although she did not say anything herself.

“I expected the first day to be devoted to routine matters,” she said later. “But apparently we are off to a really fast start. I am pleased we got some issues of substance up for debate the first day.” One important activity that she wished had been saved for another day was the drawing that would determine which senators would serve four-year and which would serve two-year terms. Under the Texas constitution, one half the members were elected every two years. When redistricting occurred as it had in 1965, it was necessary to hold a drawing to determine who would be the unfortunate ones.

Thirty-one numbered slips of paper were placed in a hopper. Some numbers meant four years, others two. During the drawing there was an air of nervous hilarity in the Senate chamber. Cries of “Post time!” and “Hey, what are the odds?” sounded as each senator approached the hopper and drew a slip of paper. As the number on the slip was read, the assemblage would either explode into cheers or murmur expressions of sympathy.

When Barbara’s turn came, the others were quiet. She was not part of the back-slapping, “good ole boy” relationship the others enjoyed. Calmly, aware that all eyes were on her, she reached in and selected her slip. The number represented a two-year term. Her colleagues remained silent, but the sense of irony that the only Black senator was one of the unlucky ones must have been running through all their minds. Barbara showed no reaction. This meant, of course, that she would have to run for office again the next year. It would be costly and time-consuming. But she decided not to worry about it until the time came.

The day’s session over, she was accompanied by her supporters to her fourth-floor office in the Capitol building. Sitting in the chair behind her desk for the first time was the occasion for a ceremony, as was her every act on that very special day. She signed her autograph hundreds of times, posed for countless pictures. She was tired, but she understood how important this day was to her well-wishers, and so she serenely signed her name and endured the popping flashbulbs and smiled at the jubilation around her, and she would be just as patient during the weeks of receptions and parties that would follow. But she looked forward to the time when she would sit in session with the other senators and get down to business, when she could begin working for the changes she intended to bring about, when she could really start being a legislator.

It promised to be an interesting session. By its very smallness, the thirty-one-member Senate concentrated a great deal of power in the hands of a few. A determined group of only eleven could successfully block action on any bill, and as a result of the November election there were twelve senators generally regarded as conservative, twelve generally seen as liberal, and seven that could be described as moderates.

Each state legislature sets its own procedure and rules. In some legislatures such rules and procedures are fairly standard and relatively easy to understand. Not so in Texas. The rules of its legislature are among the most arcane and complicated in the country. They had been established by the Constitution of 1876 and had changed little since then, although twentieth-century politics was far different from that of the nineteenth century. For example, the framers of the Texas Constitution had provided for a semiannual legislature, two sessions being enough for the state lawmakers to complete their business in the 1870s. By the 1960s, however, two sessions per year just did not allow enough time for consideration of all the bills that came before each house. During the last days of each session there was a mad scramble to complete all unfinished business before the closing. Hundreds of bills were still waiting to be considered and voted on, making it necessary for the legislators to sit in session until the early morning hours and to vote on bills without having an adequate opportunity to study them.

The Texas legislature also gives its joint “conference committees” an inordinate amount of power. In most legislatures such conference committees, comprised of members of both houses, meet to work out compromises when both houses have passed very similar bills. The U.S. Congress has them. Unlike those in the U.S. Congress, however, Texas legislative conference committees are not restricted to resolving differences between similar bills. In Texas a conference committee can change every provision of both bills, and if the result is radically different from either of the original bills, it still stands and is not even subject to debate.

Some of the rules are obscure and rarely employed. Yet to the aware legislator they can come in very handy. One of the rules of the Texas House provided that five members could remove any bill from the calendar by presenting to the Speaker a written objection carrying their signatures. According to the rules of the Senate any candidate for an appointive office whose appointment had to be approved by that body could be automatically and unilaterally turned down by the senator from his or her home district.

All the rules and procedures could not be learned in a day, or even a week. One of the first things Barbara did was to study them. Every night she pored over the legislative handbooks governing rules of parliamentary procedure. Every day the legislature was in session she sat in the Senate and observed how the rules were put into practice and, generally, how more seasoned senators operated.

One of the most striking characteristics of the Texas legislature was its commitment to the interests of big business in the state. Political expert Neal Peirce once wrote, “In no other state has the control [of a single moneyed establishment] been so direct, so unambiguous, so commonly accepted.” Pick any bill under consideration in the Texas legislature and chances are it was a bill that would benefit big business, whether oil, or construction, or insurance, or computers. Traditionally the money men were conservative, and they exerted their control through conservative Democrats. Though in the past decade or so, more moderate and liberal Democrats had been elected to the legislature and more progressive legislation had been passed, none of it had really hurt the money establishment. Texas was one of the few states that still had no income tax, a situation that greatly benefited the rich.

Another striking characteristic of the Texas legislature in general was its tradition of political trading off and cooperation. It was an ancient practice of the legislature that one house was obligated to approve the actions of the other unless there was some vital reason to object, and among the members of each house a similar tradition operated. The Texas House of Representatives had what was called a “pledge card system” whereby a candidate for Speaker solicited signed promises of support from his fellow members. In return he gave verbal promises of support to them. If he gained the Speakership, those whose signed promises he held were obligated to support him, sometimes for the duration of his term and sometimes against their own better judgment. Although the Texas Senate had no such formal system, the senators engaged in similar political trading off. They traded support for a fellow senator’s favorite hill in exchange for that senator’s vote on one of their favorite measures. Most politicians engage in this sort of dealing to some degree, hut few do so with such fervor and such regularity as Texas legislators.

All of this dealing was carried on in an atmosphere of energetic, even boisterous camaraderie. There was lots of hugging and kissing and mutual praising, back slapping and joke making. The majority of the members of the Texas Senate were “good ole boys,” outwardly polite, even flattering, but inwardly tough as hardtack, full of speeches about what they wanted to do for their constituencies but firmly believing their ultimate responsibility was to the money interests and to ensuring their own re-election. They were “men’s men,” preferring the company of men, enjoying women but expecting them to remain in their place. They socialized a great deal while the legislature was in session and welcomed the favors of the lobbyists who stalked the Capitol’s halls looking for votes on measures of particular interest to the individuals and companies for whom they worked.

Barbara was certainly no stranger to the Texas “good ole boy” characteristics, and she observed their operation in the Senate. But she did not imitate them. She knew she could not be accepted as “one of the boys,” and she wasn’t even going to try. The only way she was going to be an effective legislator was to be one who had done her homework. Within a month senators were seeking her out to discuss parliamentary points and to get advice.

On March 15, two months after she took her oath of office, Barbara Jordan made her “maiden speech” on the floor of the Senate. Previously, she had sponsored or co-sponsored several bills—she was co-sponsor of a bill that would make it a felony to disturb people who were peacefully and lawfully picketing and sponsor of three bills affecting auto insurance for Texans—but introducing a bill does not require making a speech. The matter of a city sales tax was before the Senate.

It would allow cities to vote on whether or not they wished a one-cent city sales tax levied on their respective cities. A number of city mayors were in favor of the tax, as were a number of senators. But many senators were against the bill. Barbara was one of them. Rumor had it that these senators, all liberal Democrats, intended a filibuster on the bill, which meant that they would speak for days if necessary in order to stall action and hopefully wear down their opposition.

“Senator Jordan told me she wanted to be heard on the bill,” Lieutenant Governor Preston Smith told reporters. “This is her first request to be heard. She indicated she might make some remarks.”

Would she be a part of a filibuster? To the reporters’ questions she answered that she was not planning a filibuster, but, then, there were others who intended to speak against the bill, too. “I have no idea how long these people will take to state their objections,” she said. “I’m not planning to filibuster. I’m just planning to state all of my objections to that bill.”

In her speech she called the bill “the absolute worst form of city sales tax that has been proposed in any state” and stated that it would be too great a burden on underprivileged Blacks and Latin Americans, citing statistics in support of her statement.

“Forty percent of the people of this state make under $3,000 a year, which the federal government has designated as the poverty level. …Where is the equity in a situation where the people who earn the most pay the least tax and those who earn the least pay the most?” It was a good speech, and delivered in Barbara’s weighty, skillful manner, it was even better. Senator Schwartz praised the speech as the finest maiden speech ever made by a Texas senator in his memory. Barbara realized he might be prejudiced—he was the most vocal opponent of the bill. Still, she was pleased about his praise and quite satisfied with her speech herself. The city tax bill was passed, but not without a good fight from, among others, freshman Senator Barbara Jordan.

By now she felt comfortable as a senator. She was earning the respect of her colleagues, and that was what she wanted. She had encountered no discriminatory remarks or situations. When she was not back in Houston, she lived in a four-unit apartment building near the Capitol in which she was the only Black tenant. The fact that she was Black was too evident not to be noticed, but more and more she was seen as a legislator rather than as a Black. She encouraged that view by not seeking out the company of her two fellow Black legislators. She did not deliberately avoid them. They were in the House of Representatives, she was in the Senate. Had she sought them out, she would not have improved her legislative position and she might have opened herself to criticism for either trying to start a Black “bloc,” small as it was, or for being too insecure to go it alone.

Power and influence obviously did not lie in playing “Black politics”—not in the Texas legislature in the late 1960s, and particularly not in the Senate. “The Texas Senate was touted as the state’s most exclusive club,” she recalls. “To be effective, I had to get inside the club, not just inside the chamber. I singled out the most influential and powerful members and was determined to gain their respect.”

One such senator was Dorsey Hardeman of San Angelo, chairman of the Senate State Affairs Council. “Senator Hardeman knew the rules of the Senate better than any other member,” says Barbara. “In order to gain his respect, I too had to know the rules. I learned the rules.”

In late April an air pollution bill was introduced in the Senate by Cris Cole of Harris County. On its face it was a good bill, intended to strengthen state and local control of air pollution. But an amendment to the bill had been introduced that would prevent anyone in Texas who was not an individual citizen or private corporation from suing either to lessen pollution or to recover damages caused by it. Cole was in favor of it. Barbara and some other senators were concerned especially that the right to sue would be denied to cities.

Barbara introduced an amendment specifying that nothing in the bill should prevent cities from having the right to sue. She admits that in seeking passage she tried to get around some of the parliamentary fine points—”a tactic,” she recalls, “for which Hardeman was noted and which he practiced masterfully. I almost succeeded until Senator Hardeman started to listen to what I was saying.”

“What are you trying to do?” Hardeman demanded. Barbara looked over at the senator. “It’s simple,” she said. “I’m using the tricker’s tricks.”

Hardeman was stunned for a moment. Then he chuckled; soon he was laughing out loud. “His respect for me was affirmed at that time,” says Barbara.

Cris Cole wasn’t laughing. He was already angry about the response to the amendment he favored. When he heard the text of Barbara’s amendment, he became furious.

“What have the cities done with their power? Not a thing!” he shouted.

“I have more faith in the government of the city of Houston and the county of Harris than does the senator from—what is your district, Senator?” she asked of her fellow Harris County Democrat.

When used appropriately, sarcasm can be a most effective weapon. Barbara Jordan used it to great effect with Cole, whose shouting quickly subsided. She would become well-known for her ability to shrivel an opponent with a few well-chosen words or phrases. No one, least of all her target, will ever forget what she said to a hapless representative of the National Pollution Control Board. Fixing her laserlike gaze upon him, her voice dripping contempt, she demolished him with one sentence: “I have heard your statement, and it is full of weasel words.”

Barbara Jordan’s amendment was adopted.

The next day she received an official commendation from the Houston City Council because, as Councilman Bill Elliott said, she “demonstrated amazing resistance to pressure and interest in effective pollution control.” Less than a week later Barbara was embroiled in another courageous fight, this time about a new voter registration bill. The bill, sponsored by Senator Tom Creighton of Mineral Wells, would require registration in person rather than by mail and only between October 1 and January 31 and it would require voting applicants to state whether they could write their names and whether they had any physical disability that would prevent them from being able to mark the ballot. In Barbara’s view it was a thinly veiled attempt to hamper voter registration by poor and minority people. “It is alien to the concept that the right to vote ought to be easily accessible and available to all people with minimum details and procedures for registering,” she said.

But merely objecting to a bill was not enough to block its passage. She had to marshal a sufficient number of votes against it. In the Senate sixteen votes were required to pass a bill, but twenty-one were needed to bring it to the floor for consideration. The time to block it was before it ever reached the floor. “I opposed it,” Barbara recalls, “and needed ten other senators to join me. I made a list of ten senators who were in my political debt. I needed their votes in order to keep the Creighton proposal from Senate deliberation. Armed with ten commitments, I went to Senator Creighton and asked when he planned to bring the bill to the floor of the Senate. He smiled, but with resignation, and said, ‘I too can count; the bill is dead, Barbara.'”

Barbara has described what she calls the typical Texas politician as “tough, expansive, and pragmatic.” “Lyndon Johnson was the prototype of the Texas politician,” she says. She got along well with Johnson and was gratified that he had taken a special interest in her. Several times she was invited to functions at the White House, an honor rarely accorded a mere state senator.

Men like Creighton and Hardeman were also, in Barbara’s opinion, typical Texas politicians—”conservative, decent, and practical. I respect them.” During her first term in the Texas Senate, Barbara, in turn, earned their respect.

“Her integrity is without question,” Hardeman once said. “By that I mean she will never tell you one thing and do something else. She has demonstrated great ability, and she is my good friend.”

“She’s one of the most intelligent women I’ve ever met,” has been said by so many senators that it is not worth listing their names. At the end of the legislative session, they themselves listed their names in a unique tribute.

On Saturday, May 27, the Texas Senate granted its first Black female member an unusual honor. The thirty other senators unanimously passed a resolution congratulating her for her service to the state and for the way she had conducted herself as a freshman senator, and expressing its “warmest regard and affection” to her. The resolution read in part: “She has earned the esteem and respect of her fellow senators by the dignified manner in which she has conducted herself while serving in the legislature, and because of her sincerity, her genuine concern for others, and her forceful speaking ability, and she has been a credit to her state as well as to her race.”

Senator Dorsey Hardeman then rose and asked that the names of all senators and the lieutenant governor be added for unquestioned unanimity. Then Barbara was called on to respond.

For the first time in the Senate chamber, and for one of the rare times in her public life, Barbara struggled to fight back tears. She knew how rare was this tribute. She rose to speak, and her voice broke slightly before she regained her famous self-control.

“When I came here on the 10th day of January, you were all strangers. There were perhaps mutual suspicions, tensions, and apprehensions. Now, I believe they have been replaced by mutual respect.

“I am proud to be a part of this body. I consider all of you my friends and I just want to thank you.”

The applause was thunderous and prolonged as she made her way around the Senate floor, shaking the hands of each senator. When at last she returned to her seat, she knew without a doubt that she had been accepted by the Texas Senate.

She thought back on the years of work and hope that had been required even to get to the Senate chamber, the times when she was dispirited and wondered whether she should go someplace where it would be easier for a Black woman with political hopes. Now, more than ever, she knew it had all been worthwhile. She was glad she had stayed in Texas.