9 Governor for a Day and Congresswoman-Elect

A traditional custom in Texas was for both the governor and the lieutenant governor to leave the state for a day, allowing the Senate president pro tempore a day as governor. A week after the Democratic primary, it was announced that both Governor Preston Smith and Lieutenant Governor Ben Barnes would be out of the state on June 10. That would be Barbara’s day as governor.

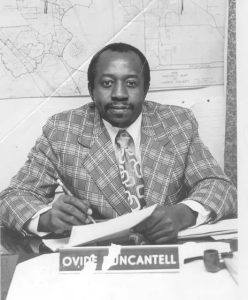

Immediately, Barbara was placed in a difficult role because she was Black and she was placed in this position by another Black. Back in 1968, Lee Otis Johnson, who had gained notoriety during the civil rights disorders at Texas Southern University in 1967-1968, had been sentenced to thirty years in prison for giving a marijuana cigarette to an undercover police officer. Many Black people had felt that that was an unduly harsh sentence and that Johnson had not received a fair trial because of the unfavorable climate of opinion in Houston at the time. When it was announced that Barbara would be governor for a day on June 10, a Black activist named Ovide Duncantell decided to ask her to pardon Johnson. He made his announcement on the lawn in front of her law offices, on a day when she was out of town.

The issue was soon laid to rest. Returning to Houston, Barbara responded to Duncantell’s request by pointing out that only the State Board of Pardons and Paroles could grant Johnson a pardon. “Not even Preston Smith himself could now grant Lee Otis Johnson an executive pardon,” she explained. She handled the matter well with reasonable arguments devoid of emotional content. But it had been an insult just the same. It was hard enough contending with whites without having to be on guard against her own people.

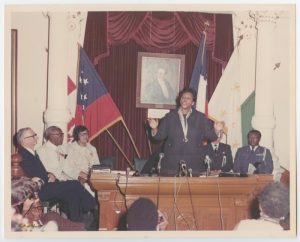

The press called it “History in One Day,” but it had taken Barbara Jordan a lot longer than that to arrive at the position of influence in Texas politics that enabled her to become “governor” and thus the only Black woman in United States history ever to preside over an entire state (if only for one day). But all the work and frustration had been worth it, she decided, as she passed through lines of cheering spectators on her way to the Capitol building at 9:30 on the morning of Saturday, June 10.

Inside the Senate chamber her fellow senators rose to applaud her, and the galleries burst with smiling well-wishers. With her mother and father beside her, she took the oath of office on the platform that held the Senate’s chief executive chair, a platform somewhat altered in appearance for this one day. Only five of the traditional “Six Flags over Texas” were in place. The flag of the Confederacy had been removed. “I didn’t issue any proclamation or edict requiring the flag to be removed,” Barbara said later. “I think those in charge felt it would not be proper for a governor of . . . this race.”

After she took the oath, Leon Jaworski, now president of the American Bar Association, spoke. Some of his remarks would prove to be prophetic:

“We are proud of you on this day, as we have been on other days; and may you, for the benefit of the society that is ours, continue to lead us to achievement of the greatest of all goals of good citizenship—that of forming a more perfect union.”

Barbara had been part of a movement sponsored by the American Bar Association to give students a better understanding of the duties and obligations of citizenship. Said Jaworski, “The greatest compliment we could pay Governor Jordan on this day is to give our unstinting support to this endeavor in the Texas schools…she believes in the processes of a democracy, upholding the standards that made this country great and deploring those that would erode its greatness.”

The speeches over, the spectators gave her another standing ovation. A reception and press conference were scheduled next. As she hugged her parents, Barbara noticed that her father did not look well. His heart condition had forced him to retire even from his activities as a minister in January, at the age of sixty-nine. He was just tired from the morning’s excitement, he assured her. Would she mind if he did not go to the reception? He would just go out to the car and rest awhile.

Barbara and the rest of her family made their way to her office, where she spoke to reporters and greeted the hundreds of people who had come to see her sworn in. A barbecue luncheon was to be held on the Capitol grounds and an afternoon ceremony was to be held on the Capitol steps.

At about 11:30 Barbara’s brother-in-law, John McGowan, took Reverend Jordan to the hospital. He had suffered a stroke. Barbara asked about his condition and was told it was “satisfactory.” So she remained in the Capitol, executing her largely ceremonial duties as “Governor for a Day.”

She signed three proclamations, one of which praised the work of the Sickle Cell Disease Research Foundation. Sickle cell anemia is an inherited blood disease found almost exclusively in Blacks. “Governor” Jordan declared September “Sickle Cell Disease Control Month” in Texas. The other proclamations praised the work of the Texas Commission for the Blind and the City of Austin. She was also handed a proclamation from Mayor Welch of Houston declaring the day as “Governor Barbara Jordan Day” in Houston. Some observers pooh-poohed the whole affair as a publicity stunt, but that didn’t bother Barbara. She kept her sense of humor, which nearly always contained a serious note. “Someday I may want to retain the governor’s chair for a longer period of time,” she said. Reverend Benjamin M. Jordan died about twenty-four hours after he was admitted to the hospital. Although she was saddened by her father’s death, Barbara was thankful that at least he had lived to see her sworn in as Governor for a Day. From the time she had been able to understand the concept, he had encouraged her to be as much as she could be, and he had worked very hard to finance her education. He had lived to see his efforts rewarded. In a way, she told a friend, it was beautiful that he had died at just that time.

The Jordan family established a Reverend B. M. Jordan Memorial Scholarship Fund. All his life he had emphasized “brain power,” and he would have been pleased to be remembered in this way. One of the trustees of the fund was Leon Jaworski.

One week after Barbara’s day as governor, five men were caught breaking into and bugging the Democratic National Committee Headquarters at the Watergate complex in Washington, D.C. There was little question that the “plumbers,” as the group called themselves, had been working for the Committee to re-elect the President, and some people suspected that high officials in the Nixon administration had authorized, or at least known about, the break-in. The FBI began an investigation of the Watergate affair, but its investigation was limited to the men who had been directly involved, and calls for a more in-depth investigation were ignored.

Back in Texas, Barbara’s day as governor had completed her term as president pro tempore of the Senate. She was succeeded by her friend Chet Brooks, who was elected to the position for the special session of the Senate that convened in mid-June. It would be Barbara’s last session. Autumn was fast approaching, and with it the November elections.

In September she received another honor. Democratic gubernatorial nominee Dolph Briscoe wanted a Black person in a high Democratic party post, either as vice-chairman of the State Democratic Executive Committee or as a Democratic national committeewoman. As the most politically prominent Black person in the state, and a woman besides, Barbara was the logical choice. She became the first Black vice-chairman of the State Committee, a position which automatically gave her a half vote on the National Committee.

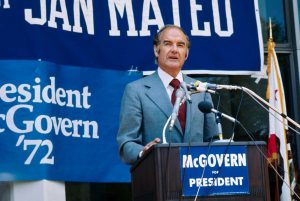

The Democratic National Convention of 1972 was very different from that of 1968. Back in 1968, many groups that had no voice in national politics had protested, violence had erupted, and the image of the party had been tarnished. But changes had been made in the process of delegate selection in the intervening four years, and when the 1972 convention opened, there were more female, minority, and young delegates than ever before. The majority of them supported Senator George McGovern of South Dakota for the presidential nomination, because he had pledged to end U.S. involvement in Vietnam, to introduce programs that would benefit the poor, and generally to speak to the issues they thought were important. Barbara supported McGovern. He was designated the Democratic Party’s candidate; and though he faced a tough campaign against President Nixon, he and his supporters had faith that through his fine character, his deep religious conviction, and the sincerity of his wish to help the people who needed help, he would win.

McGovern’s nomination proved to be the high point of his campaign; from then on it went steadily downhill. In response to persistent rumors, Senator Thomas Eagleton, McGovern’s choice for vice-presidential candidate, revealed to McGovern and the press that he had been hospitalized for “nervous exhaustion” three times in his life. The revelation was followed by questions about his mental stability. The press was full of stories about it. Fearing that a Democratic ticket that included Eagleton would lose the election in November, McGovern decided after some delay to take Eagleton off the ticket. R. Sargent Shriver, McGovern’s seventh choice, agreed to be his new running mate. It will never be known how the Eagleton candidacy would have affected the Democrats’ chances. It is known that many people were disappointed in George McGovern for not standing behind his first choice for vice-presidential nominee. Many had been first attracted to him because he seemed different from most politicians. In changing running-mates, he seemed to be putting political considerations over human considerations, just like other politicians. Other voters felt McGovern was just too liberal, even radical, too closely associated with minorities and youth.

The Democrats tried to make the Watergate break-in a campaign issue, but the general attitude of the country was that it had been an isolated occurrence, that such activities were common among both Democrats and Republicans, and that President Nixon had been unaware of the plot. In the November election, many Democrats crossed party lines and voted Republican, and Richard Nixon won by a landslide.

In Texas, Barbara Jordan also won by a landslide, capturing 80 percent of the vote against her Republican opponent, just as she had done in the May Democratic primary against Curtis Graves. She and Andrew Young of Georgia, also elected that year, would be the first Black representatives from the South since 1901; Barbara would also be the first Black Congresswoman from the South. “I feel great,” she said.

A month later, she would indicate just how good she felt and just how self-confident she was. In mid-December, she spoke at a civil rights symposium marking the opening to researchers of former President Lyndon Johnson’s civil rights papers. “Texas has done a lot for this country,” she said. “It has given you Lyndon Johnson, and now we’ve given you Barbara Jordan.”

She was proud of her victory and proud of her record during her terms in the Texas Senate. She had seen about half the bills she introduced enacted into law, including a Texas Fair Employment Practices Commission, the state’s first minimum wage law, and an improved workmen’s compensation act. She had backed successful measures to strengthen environmental protection laws and to create a special department of community affairs to deal with the problems of the state’s growing urban areas, and she had prevented passage of a discriminatory voter registration act. She believed she had truly represented the people who had elected her and earned the respect even of those who hadn’t, and she felt her large vote total in the general election proved her belief was correct. “If I got 80 percent of the votes, lots of white people voted for me,” she said shortly after the election, “and it was because they felt their interests would be included.”

There were those who disagreed with her assessment of her senatorial achievements. Curtis Graves was not the only one who called her a “sellout,” although he was clearly the most vocal. Some liberal senators felt she had hurt their cause:

“I’d carry a bill on some problem, a strong bill,” said one. “Barbara would carry one too, but it would be weak. And it would get through. The trouble with passing a weak bill is that you won’t get another crack at strengthening it for twenty-five, thirty years. Whereas if you just hold firm, you’ll get a tough one through, this session or next. It was great for the establishment to have her on their side. Whenever we tried to do anything, they could say, ‘But Barbara doesn’t think it needs to be that strong, and if Barbara doesn’t think so . . .'”

There was also the controversy over whether or not she had had to “cooperate” with conservatives in order to get the new 18th Congressional District drawn the way she wanted it. Reporters, always interested in controversy, frequently brought up these charges, although it was a rare reporter who ever brought them up more than once. Barbara would flatly deny them, and as reporter Molly Ivans once wrote, “When Jordan denies something in her weighty, absolute fashion, even the most persistent reporter doesn’t feel like bringing it up again.”

After the November election, Barbara didn’t stay around long to give press interviews. Harvard University, which sixteen years before had refused to accept a poor Black girl from a small all-Black southern college, had named her a fellow at the Institute of Politics of its John F. Kennedy School of Government. She would be one of four newly elected representatives in an experimental, month-long “cram course” designed to prepare them for their new lives as members of Congress. In addition to Barbara, another Texan, Alan Steelman, and another Black woman, Yvonne Braithwaite Burke of California, were taking the course. The fourth new member was William Cohen of Maine.

The curriculum ranged from informal lectures on how to choose an office and file a bill to briefings on major issues. The four engaged in mock debates, as if they were speaking on the House floor, and early on Barbara called attention to a problem female representatives faced. According to rules of congressional decorum, legislators had traditionally referred to a colleague as “the gentleman from Massachusetts” or “the gentleman from Utah.” With the entrance of women into Congress, the term had to be changed and “gentlelady” had come into use. “May I object to being called ‘gentlelady’?” asked Barbara during one of the seminars at Harvard. “How would you want to be addressed?” asked her fellow Texan, Alan Steelman. “I don’t know, but I don’t like ‘gentlelady,'” Barbara answered. One suggested solution was for Barbara to make a brief speech early in the congressional session to make her wishes known. But after thinking the matter over, Barbara decided such a speech would be petty and would call negative attention to the fact that she was a woman in a body in which the overwhelming majority were men. Though she would never be happy with it, Barbara resigned herself to being called “gentlelady.” She would become famous as the “gentlelady from Texas.”