4 …Realized

Barbara stayed in Texas. She resumed her law practice, but it remained small and not particularly lucrative. When she was offered a job as an administrative assistant to Harris County Judge Bill Elliott, she eagerly accepted it, becoming the first Black to be appointed to such a high county position. And it was a position with real responsibilities, “not,” as Barbara once put it, “as head Negro in charge of nothing.”

As administrative assistant for welfare, her job was to coordinate the activities of the various welfare agencies and projects in Harris County. It involved luncheons, meetings, talking with people in need of welfare, and was very different from her law practice, in which she had dealt mainly with individuals and with the courts.

“I’m enjoying it,” she said after a month on the job, “and I have no regrets about leaving law practice. In this job I feel I can help more people reach meaningful solutions to welfare problems.”

She had other reasons for accepting the job. Her father had retired, and aware of the sacrifices he had made to finance her schooling, she was eager to help him now that he was no longer working. Most of all, however, she wanted to prove to him that his sacrifices had been worthwhile, that she would indeed become something outstanding. At times she despaired that she ever could.

Conditions had improved for Blacks and women, but there were still many barriers before them. Had Barbara tried to run for the Texas legislature ten years earlier, she probably would have been laughed out of Houston. In 1962 and 1964 her prospects were greater, but the barriers presented by the Texas county electoral system counteracted the growing willingness of Texas voters to put aside considerations of race and sex in selecting their representatives. There were still many inequities under which Blacks in Texas had to live.

Most Houston whites did not recognize those inequities, or if they did, they did not consider them improper. On the whole, white Houston was proud of its progress in desegregation of public facilities, restaurants, theaters, and hotels. The municipal golf course had been desegregated in 1950; the public library had integrated its facilities in 1953; segregation on city buses had ended in 1954; discrimination in city-owned buildings was eliminated in 1962. There hadn’t been a protest demonstration since 1960; and though desegregation of the schools was proceeding slowly, the Black wards in the city, with a greater population than in any other city in the South, seemed quiet. At a March 1965 conference of mayors, Houston Mayor Louie Welch stated confidently, “We have no race problem in Houston.”

Mayor Welch was in for a surprise. Less than two months later, on May 10, more than 9,000 students stayed away from their Black high schools and hundreds of Blacks marched through the city to protest school segregation. As they marched, they sang the freedom songs that had become familiar in the rest of the South but had never before been heard in Houston.

Houston’s officials, and its white population in general, could not understand the protest. They had thought they knew what was going on in the Black communities. They hadn’t realized they only knew what a small group of Black leaders told them was going on.

These acknowledged Black leaders numbered no more than half a dozen. The oldest was in his eighties, the youngest in his fifties. For years they had been the primary channel through which Houston Blacks had communicated with Houston’s white leaders. They had voiced Negroes’ complaints about unpaved streets and poor city services, police brutality, lack of representation in government and business, and had, as the Houston Chronicle put it, “been invited behind closed doors to receive, on behalf of the Negro community, desegregation of public places, theaters, restaurants, hotels.”

In the days when ordinary Black people had no voice, these leaders served a valuable function. Their diplomatic, accommodating style was the only way to approach the white leadership, and if it had not been for them there would have been little or no communication between the races. These men, businessmen and ministers, had occupied a special position, aloof from the general Black population. For many years, Blacks had believed that was the way leaders should be. But the civil rights movement and Negro gains in the early 1960s—gains that had been accomplished frequently by activity on the grass-roots level—had brought about a change in most Blacks’ opinions regarding the characteristics of good leaders. By 1964, many Houston Blacks believed their leaders should be aggressive rather than accommodating, people with whom they could identify rather than people who were aloof. They began to look to a new, younger leadership, leaders who could help them build quickly on the gains they had made. As Barbara once said, “Change we must, the young people are on our heels. They are saying to us, ‘We don’t want any more of your old-fashioned shucking and jiving and we aren’t having any more of the old-fashioned acceptable Negroes.'” Barbara Jordan was of the new type of leadership.

The idea of boycotting the schools was that of thirty-six-year-old Reverend William Lawson, and he had begun his campaign by meeting with fewer than fifty students at a single school. As the campaign had gained momentum, he had contacted others to help him. Barbara had known him at T.S.U., where he had arrived in 1955 as a student rector. In the boycott she served on his strategy committee, and in the march that represented the culmination of the boycott campaign she strode purposively with him at the head and sang freedom songs in her commanding voice.

When he learned of the march, Mayor Welch hurried to the school administration building to wait for the protestors. They marched right past him. One of the older Black community leaders had joined the front lines of the marchers, and as they neared the school district offices, he offered to act as a liaison between Reverend Lawson and Mayor Welch. Lawson ignored him completely. “It was at that moment,” said one observer, “that Lawson took the leadership [of the Black community].”

Desegregation of Houston’s public schools proceeded more rapidly after that, the schools completing desegregation in 1966-1967, and for the Black community as a whole, there was a feeling of greater control over their own lives. While Barbara Jordan was pleased about the progress, she was still concerned about the political situation of Blacks in Houston and about the progress of her own political career.

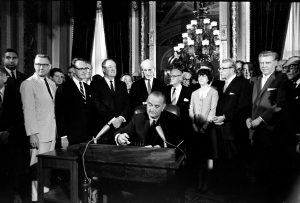

Between 1964 and 1966, changes in national laws and the enforcement in Texas of civil rights laws passed earlier altered the state’s electoral system and removed the barriers that had prevented Barbara Jordan from realizing her goals. The civil rights movement had steadily gained momentum since 1959, when a group of students chiefly from Black southern colleges had formed the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (S.N.C.C.) and started massive voter registration drives in Mississippi, Georgia, and Alabama. Resistance on the part of whites in these states was frightening in its ferocity. Young workers, Black and white, as well as the Blacks whom they were trying to register, were taunted by police, threatened by white citizens’ groups, arrested, jailed, beaten. Some were even killed. In Mississippi during the summer of 1964, S.N.C.C. and its supporters suffered at least one thousand arrests, thirty-five shootings, eight beatings, and six murders. But the students kept on working and the eligible Black voters kept on registering, and after a while the violence in the South caused revulsion in the rest of the country. “It is wrong—deadly wrong—to deny any of your fellow Americans the vote,” said President Lyndon Johnson. A few months later, he signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965. It eliminated the poll tax and pledged the support of federal troops in registering all those eligible voters who wished to register.

Texas had not experienced the strident racial confrontations that had occurred in other parts of the South. Nevertheless, many of its eligible Black voters had been unable to afford the poll tax, and many others had been apathetic about voting. Now, convinced that at least the federal government wanted a Black voice in electoral politics, they were eager to register to vote, an eagerness that was highly encouraging to Black aspirants to political office in Texas.

Even more encouraging was the reapportionment of state House and Senate districts that occurred in Texas. In March 1962, the Supreme Court had ruled in a case known as Baker v. Carr that counties in the southern states should be divided into districts according to population so as to make the ideal system of one man-one vote a reality. Although the decision did not cover Texas, a southwestern state, and the Texas system of dividing the state only by county lines, representing acreage rather than people, continued for a time, Baker stimulated more Black voter registration in Texas, too, and made a change in its system inevitable. In 1965, the system called for under the Baker ruling was introduced to Texas and the state was reapportioned. Suddenly Barbara Jordan found herself living in a newly created state senatorial district, the 11th. It was 38 percent Black, with the rest of the population Chicano and white, and it contained 70 percent of the precincts that she had carried in the 1962 and 1964 elections. No doubt about it, Barbara Jordan would run for a seat in the Texas Senate.

Naturally she was not the only one who wanted the new Senate seat. The creation of a new seat or office always results in a scramble for it. State Representative J. C. Whitfield also announced his intention to run. “He called me before the filing deadline and asked if I was planning to run for the Senate,” Barbara remembers. “I said I was. He said he was going to run no matter what I did. It was a friendly and candid conversation.” Whitfield formally filed as a candidate on December 20.

Barbara did not file for another month and a half. There were matters to be attended to first, such as changing jobs. She had been offered a position with the Crescent Foundation, a private, nonprofit corporation under contract with the Department of Labor. A grant of $360,000 had been made to the foundation for a special project to aid “hard-core unemployables,” and the foundation needed people to direct and coordinate the project. Barbara was hired as project coordinator at a salary of $10,000 per year. The project director would be Otis H. King, who had been a classmate of Barbara’s at T.S.U. Back at Texas Southern University, Barbara and King had been together on the varsity debating team; now, some ten years later, they were together again.

Barbara resigned her position as administrative assistant to County Judge Bill Elliott at the end of December and at just about the same time announced her intention to run for the 11th District Senate seat. “Having received the overwhelming support of this same district when I campaigned for a seat in the legislature two years and four years ago,” she said, “gives me confidence that this time those who have supported me will succeed.” Still, she waited to file formally as a candidate. First, she wanted to make sure it was legal and proper for her to work at the foundation and run for the Senate at the same time. She did not feel J. C. Whitfield would get much of a head start campaigning. Based on their telephone conversation she anticipated a tough but clean fight with him. It would prove to be otherwise.

On February 4, 1966, Barbara paid her $1,000 filing fee as a candidate for the Texas Senate in the Democratic primary contest. For the press it was a little-noticed act, but Barbara Jordan realized it was a historic occasion. Not since Reconstruction had a Negro been a candidate for the Senate. She had asked Lonnie E. Smith to be with her as she filed. Smith, a Houston dentist, had been the plaintiff in the case of Smith v. Allwright, the 1944 decision which had given Blacks the right to vote in the Democratic primary in Texas.

Barbara’s 1966 campaign for public office was considerably different from her two previous campaigns. For one thing the Texas Senate was far more exclusive and influential than the Texas House. Indeed, it was considered the state’s most exclusive club. For another her opponent for the Democratic nomination this time was a liberal. Unlike her opponent in the two previous elections, J. C. Whitfield believed in many of the same causes in which she believed and had demonstrated his stand on the issues as a state representative.

But soon Whitfield and a group of other liberal Democrats proved that in reality they were not quite as “liberal” as they had previously represented themselves as being. The reapportionment of Harris County had changed the lines of power within the Harris County Democratic Committee. When the committee met in March to decide which of the Democratic primary candidates they would endorse, Whitfield and some other candidates for the legislature asked for co-endorsement of nine candidates, which meant that the committee would endorse both Whitfield and Barbara Jordan for the same seat.

Many on the committee opposed the idea. They wanted to endorse the slate supported by a Democratic coalition composed of representatives of labor groups, Latin American groups, and the Harris County Council of Negro Organizations, a slate that included the name of Barbara Jordan. In reaction to their opposition an angry Whitfield changed his stance and claimed Barbara Jordan had no qualifications for endorsement and did not truly represent the people.

With that Barbara rose. In her commanding voice and appearing to look every member of the gathering straight in the eye, she said: “I live in this district and I was born in this district and these are the people I am representative of.” The crowd rose to give her a standing ovation, one of four she received that night.

Angered by their inability to influence the meeting, Whitfield and about fifty others walked out and announced the establishment of a rival liberal Democratic organization, the East Side Democrats. The split could have proved a serious one for Harris County’s Democrats, particularly its liberal Democrats. Whitfield was powerful; if Barbara lost to him in the primary it was feared that many of her supporters, especially Blacks, would stay away from the polls in the general election, or even possibly vote Republican in some races.

Whitfield was determined to prove that Barbara was not qualified to hold the Senate seat. Soon after the explosive Harris County Democratic Committee meeting, he publicly accused her of conflict of interest. He charged that her running for the Senate seat while working as an administrator of federal funds under the War on Poverty program was improper. In telegrams to the U.S. attorney general and the secretary of labor, a copy of which he sent to the major Houston newspapers, he said: “I, as a citizen and as her opponent, request immediate investigation by your office into possible violation of federal statutes and the propriety and potential political implication of a candidate for public office having hundreds of thousands of dollars of federal funds available in her district during an election now in progress.”

Barbara immediately called a press conference to answer the charges. She told the assembled reporters: “Before I took the position, I asked if there would be any conflict of interest or any reason why I should not do the work while a candidate. This was checked here and in Washington, and I was assured there was no conflict or anything wrong as long as I put in a full day’s work as I have been doing. I was the first one to raise the conflict-of-interest issue and was assured there was none.”

Federal funds with which she was involved were all earmarked for employers to train unemployable people, she said. “I have absolutely nothing to say about disbursement of any of the funds. None of them is at my disposal.”

After Barbara’s response the matter was dropped. But then Whitfield tried a new tack. Bringing to public attention the ethnic makeup of the new senatorial district, he used as his slogan, “Can a white man still win?”

Barbara had always been an issue-oriented candidate and did not care to become involved in questions of personality or race or sex. But Whitfield had introduced the racial issue into the campaign and she would not let it go unanswered. Her response to his slogan was a slogan of her own: “No, not this time.” Otherwise, she refused to exploit the racial difference between herself and her opponent. She won the Democratic primary by a vote margin of two to one (19,317 to 9,772), and though the November 8th general election was still ahead, in Texas in those days winning the Democratic primary was tantamount to winning the election.

On the evening of primary day, as the vote counts came in and Barbara’s victory became apparent, hundreds of friends and relatives crowded into her headquarters at the True Level Lodge on Lyons Street, and those who could not fit inside cheered and sang in the streets outside. Between hugs from her parents and sisters she beamed with pleasure: “This is really great. It’s good to be a winner after two defeats for the state House.”

Among the well-wishers was County Judge Bill Elliott. Barbara had quit her job in his office the previous December to begin her campaign, but she had left no hard feelings behind her. “This is just a first step for her,” Elliott said on election night. “We will be hearing a lot more from Barbara Jordan. In the Senate she will be a credit to the Negro race, the white race, and all the races. We’re extremely happy to see her win.” It is no longer acceptable to refer to a minority person as “a credit to his or her race.” After all, as Black people pointed out in the late 1960s, the phrase seems to indicate that the majority of the race are not “credits.” No white person was ever described that way. Barbara was not particularly pleased with this “faint praise” in 1966, but she understood that it was well-meant. She also realized that she would be watched closely to see how she would perform in the Texas Senate. She determined not to make any mistakes.

Part of her “dignified senator” image was not to show her joy at winning. After the initial flush of victory, she made only one more public statement that indicated how much of herself she had invested in the campaign. She had expected to win, she said, “but I would not allow myself to believe it, for fear I would not work as hard. I worked hard for this.”

Congratulatory telephone calls and telegrams came in from the Speaker of the Texas House and ten state senators, and Lieutenant Governor Preston Smith assured her he was looking forward to working with her. “The state leadership has recognized the historical inevitability of a Negro being elected,” Barbara told reporters. “They were psychologically prepared.”

Although she had not as yet actually won the Senate seat, she had no Republican opponent and she hardly needed to campaign against the Constitution Party nominee, Bob Chapman. From the primary onward Barbara spoke as a newly elected state senator.

She was constantly asked how, as the only Black in the Senate, she would act. “Of course I can’t ignore the fact of my race—it’s too evident,” she would say with a smile. “Naturally I will be interested in any legislation affecting Negroes.” But she intended to stand on her campaign promises to help better the lives of all Texans, particularly those who had never before had anyone to speak for them in the state legislature.

Meanwhile in other parts of the South the civil rights movement had taken a more militant turn. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee had undergone an ideological split in its ranks and had changed its name to the Student National Coordinating Committee. In June, S.N.C.C. leader Stokely Carmichael had raised a clenched fist and called for “Black Power!” a cry that had reverberated across the nation. Young Blacks were tired of being beaten and arrested and not reacting, as was the nonviolent way. They had suffered much in the name of integration, and many were so sickened by white violence that they no longer wanted integration. There would soon be open talk of separatism. As part of this change many were against working “within the system,” as Barbara Jordan would be doing. But for Barbara there was no conflict. “All Blacks are militants in their guts,” she says, “but militancy is expressed in different ways.”