13 The Future for Barbara Jordan

Barbara’s Texas-style initiation into politics had been very valuable, and when she reached Washington, D.C., being a representative from Texas certainly did not hurt. The Texas delegation was an extremely powerful group and had been so for a long time. Traditionally the Texas delegation had consisted almost exclusively of conservative Democrats, and there was power in such unity of political philosophy. Moreover, unlike U.S. legislators from urban areas, for whom a city judgeship was the ultimate goal, many of the Texans were former county judges from small, rural towns for whom a congressional seat was the highest goal they had ever hoped to reach. Having reached that goal, they stayed in Washington and gained seniority and maintained their cohesive force while other state delegations changed personnel frequently and amassed less seniority. The Texas delegation had achieved the height of its power in the 1950s, when Sam Rayburn was Speaker of the House and Lyndon B. Johnson was Senate majority leader. Through a combination of tenacity, traditional Texas-style political wheeling and dealing, and the financial support of the money interests back home, the Texans were the most formidable bloc in Congress.

By the time Barbara reached Washington, the power of the Texas club had begun to ebb. Congressional redistricting due to one-person-one-vote court decisions had eliminated some of the old rural districts, and new members elected from the big cities were often either Republicans or more liberal Democrats. The seniority system was beginning to come under fire, and some of the elderly Texans who were powerful committee chairmen were close to retirement. But in the 94th Congress, Texans were still in control of nearly one third of the twenty-one standing committees of the House and of more than twelve subcommittees.

Just being from Texas, however, didn’t automatically constitute acceptance in the Texas club. Acceptance from its older, powerful members had to be earned, and Barbara had done it in a remarkably short time. She understood their politics and proved quickly that she knew just as much as they did, if not more, about oil depletion allowances and cotton prices and the Dallas money market, as well as civil rights law and the provisions of the Equal Rights Amendment. What’s more, she fit in well with them, didn’t assert either her Blackness or her femaleness, didn’t make them feel uncomfortable. Once accepted, she became a “card-carrying member” of the club. In addition to attending the weekly meetings of the delegation, she had lunch with them, made contacts through them, sounded them out on issues. Her approach has always been to “seek out the power points,” and there is no more powerful group in the House.

As stated before, her close association with the otherwise white, male Texas delegation has given rise to criticism from those who feel she should be more conspicuously on the side of issues directly affecting Blacks and women. Very soon after she arrived in Washington, she made clear her feelings that the Congressional Black Caucus should concentrate on legislation rather than on taking public, general positions. “There are bills which come up and which affect Black people directly,” she says, “and in my judgment the Black Caucus ought to be looking for those pieces of legislation and seeing to it that amendments are offered which would change the impact if that impact would be negative or adverse to Black people. I have told my Black Caucus colleagues that we cannot be the Urban League, the N.A.A.C.P., the Urban Coalition, the Afro-Americans for Black Unity, all rolled into one. We have a commonality of issue—Blackness—but we cannot do what the other organizations have been designed to do through the years.”

She attends meetings of the House women’s group only when she has time. She makes a firm distinction between working and “crusading.” Recurring throughout her career have been the charges that she is a “sellout” to white, conservative interests. She prefers the word “compromise” to “sellout.” “I think compromise is necessary,” she says. “I don’t call it cutting deals with people: I call it trying to get done what I need to get done and making necessary compromises which do not violate principles in getting those things done. I think it’s necessary in political life.” Barbara also points out that she has never sold out her constituents on legislative issues and that there is nothing wrong in dealing with those who are powerful if you get enough in return.

She is almost religiously responsible about her job, working twelve to fourteen hours a day, spending far more than the average time on the House floor, and being present for a remarkable percentage of roll-call votes. Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., used to complain about the number of roll-call votes taken in the House: “There are men in Congress who have never contributed anything to the advancement of our nation, but sit all day on the floor of Congress, just to look around and see whether two hundred and eighteen members are present,” he said in his autobiography. “If not, they question the presence of a quorum. Then the Speaker makes a count, finds there is no quorum, and three bells are rung. One must then scurry over to answer the roll call.”

Barbara may complain privately about the number of roll-call votes that are taken in the House, but she does not question them publicly. Her record of rollcall vote participation is well over 90 percent.

As she walks back and forth between the House floor and her office, or between her office and her various committee rooms, she rarely speaks to those she passes, even if she knows them. Most of the time she is so absorbed in thought that she doesn’t notice them. She rarely enters the Washington social scene, preferring to make her contacts over lunch, for example, rather than over cocktails or at an evening reception of some sort. Because of this behavior, she has acquired a reputation for coldness and aloofness.

Barbara can indeed be cold. She is well-known for her sarcasm, such as her comment to a congressman who was regaling the Texas delegation about the high price of fertilizer one day. After listening to him for a time, she grew tired of his long-windedness. “Congressman,” she said, fixing her piercing eyes on him, “it’s refreshing to hear you talking about something you’re really deep into.”

Barbara’s administrative assistant, Rufus Myers, says: “Some people misunderstand her because they’re so used to dealing with people who are not entirely serious when they’re on the job. She just feels that when she is on the Hill taking care of the people’s business, she doesn’t have time to try and please everybody by being what they might call ‘nice.’ She just wants everybody to state their business as briefly as possible so that she can have enough time to do her job. It’s really as simple as that.”

She is decidedly not a favorite interview subject for reporters, especially for those assigned to do a personal story on her. Many an interviewer’s questions are prefaced with phrases like “I’ve been warned not to ask you about….”

“I can’t remember being more apprehensive about an interview with a public figure than I was before (and, occasionally, during) my talk with her,” wrote veteran newswoman Meg Greenfield. “The message is conveyed in her every word and gesture: Don’t tread on me. And she is also known for a certain brusqueness associated with another minority group to which she belongs: that of very smart people who see the point long before others have finished making it and who have a low threshold for muzzy argument or political blah.”

Barbara is indeed very smart, but she is not a smart aleck. Her fellow representative from Texas and friend Charles Wilson explains: “Now, Barbara doesn’t try to play possum on you; she doesn’t mind letting you know that she’s got a very, very high I.Q. But she doesn’t embarrass you by making you feel that you’re nowhere close to being as smart as she is. It’s an amazing thing how she can be standing there schooling you about something and still make you feel that you knew all that right along. Not all smart people can do that; some of them love to make you feel right ignorant.”

Certainly, there are some who do not particularly like Barbara. There are others who like her as a person very much but disagree with her politics. But there seems to be no one who does not respect her, and in Washington, respect counts almost more than anything else. Some would argue that influence is most important, but a major component of influence is respect. Other components of influence are contacts, intelligence, and the ability to get things done. Barbara has all of them, and something more. Charles Wilson tries to explain it:

“It’s that along with her superior intelligence and legislative skill she also has a certain moral authority and it’s just presence, and it all comes together in a way that sort of grabs you, maybe you’re kind of intimidated by it, and you have to listen when she speaks and you feel you must try and do what she wants….It’s something you really can’t describe.” That indescribable “something” has made Barbara Jordan, after only a very few years in Congress, one of its most influential members. In February 1975, she was the subject of a front-page profile in the Wall Street Journal (no small honor in itself), which stated that she had achieved “more honor and perhaps more power than most members . . . can look forward to in a lifetime.” In some ways, the characteristics that could very well have been strikes against her—her color, her sex, and her southwestern origins—have worked for her. We are in an age when all three of these characteristics, formerly scorned and discriminated against in politics, are now at a premium. At least on the surface, attempts are being made to give Blacks, women, and southerners a greater voice in the political process, and Barbara Jordan happens to represent all three groups.

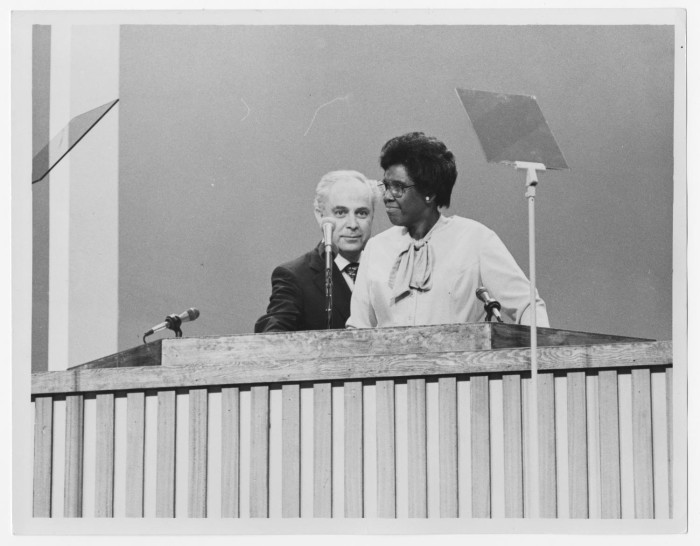

Barbara was chosen as one of the two keynote speakers at the Democratic National Convention held in New York City in July 1976. The other was a white male, former astronaut, and congressman from Ohio, John Glenn. Barbara, a Black female, was a logical choice to provide balance. But she was chosen for other reasons. Race and sex aside, she had become one of the most prominent Democrats in the country. It turned out to be a very wise choice, for Barbara’s address was the highlight of the first evening and one of the highlights of the entire convention. After a colorless and unmemorable speech by John Glenn, Barbara was introduced, and she took her place at the podium amid a standing ovation. The huge Madison Square Garden thundered with applause. She waved one hand, and the audience cheered. She raised both hands and they cheered louder and stomped their feet in delight. Smiling, she waited for the tumult to subside. Then she began:

“One hundred and forty-four years ago, members of the Democratic Party first met in convention to select a presidential candidate. Since that time Democrats have continued to convene once every four years and draft a party platform and nominate a presidential candidate. And our meeting this week is a continuation of that tradition.

“But there is something different about tonight. There is something special about tonight. What is different? What is special? I, Barbara Jordan, am a keynote speaker.”

She was interrupted by wild applause and cheering, and she would be interrupted again and again as she spoke of the problems of the country and her hopes for America. It was an impressive speech, impressively delivered in her sonorous, almost hypnotic voice; and when she finished, she received a thunderous and standing ovation. The overwhelming response was one of pride, not just from women because she was a woman, not just from Blacks because she was Black, not just from Democrats or from Texans, but from all segments of the population, because she was an American. There were tears in the eyes of many of her listeners, both at the convention and at home, and for others the breathless, almost light-headed feeling that comes after a profoundly moving experience.

A week later, on the floor of the House of Representatives, Charles Wilson moved that Barbara’s keynote address be reprinted in the Congressional Record. “I would guess there are few Republicans in the House who did not watch Ms. Jordan deliver this speech in New York,” he said, “and fewer still who did not share our pride in our colleague. Many have said so…. We Democrats in the House proved our regard and respect for the egalitarian procedures of our great convention. We sent the best we had.”

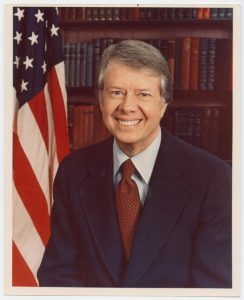

James Earl Carter won the Democratic presidential nomination at that convention against token opposition, and though he faced a hard fight against Republican incumbent Gerald Ford, he was certain he would win the election. Barbara Jordan was also optimistic. A combination of Black, northern liberal, and southern white votes could give the nation its first southern-born president since Zachary Taylor, and she looked forward to election day.

There were Blacks who were not as strongly behind Jimmy Carter. Shirley Chisholm, congresswoman from New York, and Representative Parren J. Mitchell of the District of Columbia, to name two, were concerned about Carter’s so-called “fuzziness” on issues and about his southern origins. They pointed to his conservative positions when he ran for the Georgia governorship in 1970 and to the fact that he had received only 7 percent of the Black vote in that gubernatorial election. During his primary campaign in 1970, he had visited a private academy that had a whites-only policy, and though the stated purpose of his visit was to reassure Georgians of his support for private education, the implication was that he supported school segregation. In 1972, he had praised a resolution by the Georgia legislature that called upon Congress to pass a constitutional amendment banning school busing, and in the same year he brought pressure to bear on Democrats in Congress to weaken the Voting Rights Act of 1972. Based on such a record, these Blacks were hesitant to believe in Carter’s avowed liberalism and concern with Black people.

It will be noticed, however, that the Black leaders who voiced these misgivings were nearly all non-southerners. Among southern Black leaders, only Georgia state representative Julian Bond refused to support Carter. The others found it possible to support him quite energetically despite his rather flawed past record on civil rights.

Being southerners themselves, they understood the kind of atmosphere in which Jimmy Carter had reached political maturity. His seeming fuzziness on the issues was not so much a matter of having no firm policies as it was of the kind of campaign style to which he and other southerners were accustomed. Barbara Jordan may always have run issue-oriented campaigns, but most southern candidates run now, as they have always done, personality-oriented campaigns. The new breed of southern politicians tries to project what has been called a “best man” image, emphasizing trust and integrity and basic decency more than concrete issues. That was the kind of campaign Jimmy Carter was running for the presidency.

Barbara also did not worry about Carter’s past civil rights record. Things had been changing quickly in southern politics over the past few years, and what a white southern politician said or did in 1970 or 1972 often had little connection with what he said or did in 1976. Many strident segregationists a decade earlier were openly wooing the Black vote now. As a politician, she felt, Carter had a right to change his views on issues just like anyone else. And finally there was that subtle understanding between southern Blacks and whites that neither northern whites nor northern Blacks could comprehend—a sense of knowing where one stood with the other without the shadows of false liberalism to obscure the truth—the shared pride in the South that the election of a southern-born president could do so much to bolster.

In November, it was just that coalition of Blacks, southern whites, and northern white liberals, that carried the election for Jimmy Carter, and of the three groups the Black vote constituted the most solid bloc. Carter received well over 90 percent of the Black vote nationwide. Black votes made the difference in Mississippi and Louisiana. In Texas, Barbara Jordan’s home state, Carter won the state’s bloc of twenty-six electoral votes by some 150,000, but Blacks provided 276,000 votes. No wonder Jimmy Carter has called the Voting Rights Act of 1965 the most important political event of his lifetime; it could also be called the most important single event affecting his own political career.

There was no question that Jimmy Carter owed a lot to the Blacks who had voted for him, and it was expected that he would reward his Black supporters with important government jobs. He intended to have a racially and sexually representative Cabinet, he said, and naturally, soon after the election speculation was rampant about whom he would choose. The name of Andrew J. Young, congressman from Georgia and Carter’s staunchest Black supporter, was on every list of potential Black cabinet members; and so, on many of these lists, was the name of Barbara Jordan. Perhaps she would be chosen as secretary of housing and urban development or secretary of labor. But time passed and the cabinet appointments were made, and though Andrew Young was named ambassador to the United Nations, Barbara Jordan received no appointment.

Had she been asked? Had she turned them down? Neither the Carter people nor Barbara would say. It was rumored that she had indeed been approached with regard to a cabinet post and had responded negatively, or rather, that she had informed the Carter transition team that she would only be able to accept the post for two years. Senatorial elections were coming up in 1978, and according to Washington scuttlebutt, Barbara Jordan was going to run for a Senate seat.

Barbara would neither confirm nor deny these rumors, but as more information was leaked or said to be leaked about her consideration for a cabinet post, she felt constrained to set the record straight. In April, after the President had made all his major cabinet selections, she explained in an interview with Barbara Walters what had really happened.

She had received a call from Carter back in December. He had asked her if she would be interested in “exploratory talks” with him about a position in his administration, and she had agreed to meet with him. “Anybody would talk to the President-elect,” she told Walters. “I’m not that ‘cold and aloof,'” she added, referring to her reputation. By the time she went to Blair House, the mansion across the street from the White House in which Carter and his transition team had set up operations, she had decided the only position she would even consider would be that of Attorney General. The President-elect asked for a first, second and third choice, but she had only one, and in a brief but friendly meeting she told him so.

Carter chose longtime friend and associate Griffin Bell as Attorney General, and the appointment was confirmed by Congress despite objections from some civil rights groups on his civil rights record.

Asked why she thought she had not been chosen, Barbara answered, “Well, let me state the obvious. Mr. Carter was and is entitled to his own choice, and his choice was not Barbara Jordan. Now that should end the matter. As to why I would think the chances were remote to begin with, bringing the ‘baggage’ which I have always had to carry from birth—not always a heavy baggage, sometimes light, but the Black, woman thing—it is conceivable that some in the South would have considered an appointment of me to the position of attorney general as a real slap in the face. I don’t know that such was the case, but I certainly suspect it could have entered into the consideration.”

It has been suggested, at various times and by various people, that Barbara, who has already chalked up a long string of firsts, might well be the first Black female vice president, the first Black female president, the first Black female Speaker of the House, the first Black female attorney general, the first Black female governor of Texas, the first female member of the Supreme Court, not to mention the first Black senator from the South. Publicly she has always encouraged such speculation. Back in July 1972, when she served in the honorary position of “Governor for a Day,” she stated that she might someday want to retain the governor’s chair a little longer. During a spring 1976 program of Meet the Press, when she was asked if the country was ready for a woman, particularly a Black woman, as a vice-presidential candidate, she smiled and answered, “The country is not ready, but it’s getting ready, and I’ll try to help it.”

But Barbara is a stone realist and she is aware that there are limits to her possibilities. Privately, and in moments of particular candor with reporters, she alludes to those limits. She knows it would be very difficult for her to win a statewide election in Texas. When one reporter pointed out in 1972 that Frances “Sissy” Farenthold had gotten 45 percent of the vote in that spring’s Democratic gubernatorial primary, Barbara gave the reporter her well-known, baleful glare. “Sissy’s white,” she said impatiently. “It still does make a difference, you know.”

In the same year, newly elected as the first southern Black female representative, she was asked about her future. In return she sarcastically posed another question: “Where would I go from here?”

Barbara’s realism derives from solid bases. She has not forgotten how hard it was to be elected to the Texas legislature or how much time it took Texas to integrate its public schools. The newspaper reports of bombings of Black homes in New York suburban neighborhoods or demonstrations in South Boston against busing do not escape her keen eyes. Also, being a politician par excellence, she is aware that conventional political wisdom holds that whenever the question of race comes up, it must be assumed that the American electorate is primarily made up of closet segregationists.

Though the political possibilities for Blacks in the South have advanced light years forward from what they were a decade ago, they are still not wide open or boundless. The elective positions held by southern Blacks are mostly at low levels. Only one southern Black has been elected by statewide vote: Joseph Hatchett, who won a place on the Florida Supreme Court. In the fall of 1976, Howard Lee, a Black former mayor of Chapel Hill, North Carolina, got 46 percent of the vote in a Democratic primary runoff for lieutenant governor, but it was not enough to win. One of the few Blacks in the Mississippi state legislature, Fred Banks, Jr., says: “It may take twenty years to get a Black elected to statewide office here.”

Despite these limiting factors, Barbara Jordan will probably not remain simply a representative from Texas. She aspires to, and will presumably achieve, higher political office. It is likely that whatever higher office she does achieve will he an appointive one, such as attorney general or Supreme Court justice, or if it is an elective one, it will be an office for which people who know and have worked with her will vote, like Speaker of the House. Senator Jordan? Vice-President Jordan? President Jordan? To paraphrase the point Representative Caldwell Butler once made, Barbara was probably born too early to achieve such positions.

That is the pragmatic view. But American politics is a curious blend of pragmatism and idealism. There is still room in America for strange and unusual happenings, for “rags to riches” stories, for a poor Black girl from Houston’s Fifth Ward to fulfill her dreams, whatever they may be.

Perhaps, as the United States begins its second two hundred years, its people can put aside their prejudices against sex and race in the face of the undeniable intellect and charisma of a woman like Barbara Jordan. To do so would be a testimonial to our maturity as a people, a proof to the rest of the world that a “made-up” country of many nationalities can really work, and a fitting way to greet the new era.