11 The Impeachment Hearings

On January 12, 1974, Barbara announced that she would seek a second term in Congress and would run in the May Democratic primary. But this time there was no Curtis Graves to oppose her. In fact, there was no one at all to oppose her. She was grateful for the lack of opposition, for it enabled her to devote her time to her activities in the House.

It was a busy spring. The energy crisis had become a reality to Americans, and there were massive oil shortages across the country. Barbara introduced a bill that would require oil companies to turn over information on all their activities to the government’s General Accounting Office. She also predicted that product shortages, rising prices, and the energy crisis would result in the creation by Congress of a consumer protection agency. In February, she co-sponsored with Representative Martha Griffiths a bill that would provide social security coverage to homemakers, a group that had traditionally been denied benefits because their work was done inside rather than outside the home.

Meanwhile, as a member of the House Judiciary Committee, she was busy hearing testimony and receiving evidence on the twenty-two articles of impeachment that had been introduced into the House after the Saturday Night Massacre and referred to the committee. At the end of 1973, Committee Chairman Peter Rodino had appointed Wisconsin Republican John Doar, former head of the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division under Presidents Kennedy and Johnson, as the committee’s counsel. Doar saturated the committee with evidence, and there were many nights when Barbara sat up until dawn reading pages of testimony. Yet she would not have traded her committee assignment for any other. “It is impeachment or the prospect of it that undergirds everything that’s done in the House right now,” she said in March. “If I weren’t on this committee, I’d feel like an outsider in the House, because those who are not on the Judiciary Committee don’t really know where we are with regard to impeachment, or what the plans are, or where we intend to go.”

On March 1, a special grand jury handed down an indictment against former presidential aides H. R. Haldeman and John Ehrlichman and recommended that certain material reportedly damaging to the president be forwarded to the Judiciary Committee. That material included some tape recordings of presidential conversations, and after listening to them, John Doar believed he had a case for impeachment. But to make a solid case he needed more tapes. So did Leon Jaworski. Both men asked the White House for forty-two additional tapes. The White House refused; President Nixon would not give up any more tapes. The Judiciary Committee was just conducting a “fishing expedition,” he charged.

Barbara publicly disagreed. “We are seeking six conversations related to the Watergate coverup,” she said, “and they are on forty-two separate tapes. It’s not our fault if these people are long-winded.”

And she took issue with the president’s claims that “executive privilege” enabled him to withhold the tapes. “Before impeachment, executive privilege falls,” she said. “Before impeachment, confidentiality falls. And impeachment is the one exception to the separation of powers.”

Such speeches were gaining her considerable renown in Washington circles and earning her renewed respect at home. That week a highly laudatory article about her appeared in The Christian Science Monitor. One of the politicians the article quoted was Louisiana Democratic Representative John L. Rarick, one of the House’s most conservative members and an old-line segregationist, who called her “the best congressman Texas has got.”

She did not act exclusively like a Black, a woman, or a liberal, but “like a representative in Congress,” said Rarick.

A week later, she was praised by Speaker of the House Carl Albert himself. His remarks came at a fundraising dinner honoring Barbara in Washington, at which he predicted that she would one day be chairman of the Judiciary Committee. “It’s the safest bet you can make in politics,” he said, “whether or not the House seniority system survives in its present form.

“She came to Congress in her thirties; she’ll be there in her sixties. She has the head, the heart, and the muscle to make her kind of democracy count.”

Barbara was pleased with the praise, but she felt the need to qualify Albert’s predictions: “I may be in the House of Representatives till I’m sixty-eight,” she said, “but I may want to move on to someplace else before that time. I want to be there [in Congress] as long as I want to be there.”

A few weeks later, Albert asked Barbara to preside over the House in his absence. Those who had heard the Speaker make his prediction about Barbara chuckled that if he did not watch out, she would have his job. Meanwhile, the members of the House Judiciary Committee continued their investigation into the impeachment of the president; as the evidence against him mounted, a subtle change began to occur, and the committee members began to come together: “When we began to sift through this whole morass, this mountain of information, that is when it all began to jell,” Barbara later recalled. “I can’t point to any specific revelation which caused the mood of the committee to shift, but around mid-April the partisan acrimony was reduced. People started to listen and look and make decisions.”

On April 11, the House Judiciary Committee voted, thirty-three to three, to issue a subpoena for forty-two additional tape recordings. A week later, Special Prosecutor Leon Jaworski issued a subpoena for sixty-four additional recordings. Barbara, among others, hoped that the president would comply with the subpoenas. “Realistically there is no way for the committee to enforce its subpoena. We are not going to have the specter of the sergeant-at-arms or the doorkeeper or the security counsel for the committee trying to seize the president.”

Yet, in Barbara’s view, if Nixon did not surrender the tapes, his refusal itself might be considered an impeachable offense. She was called upon to give her opinions on the matter publicly often that spring. She appeared on the Today show and on the news program Issues and Answers. In May, she was one of the two members of the Judiciary Committee chosen to discuss the matter of impeachment on the Public Broadcasting System. She was getting more national publicity than probably any other first-term member of Congress.

Some Republican congressmen criticized her for speaking so openly about impeachment, but Barbara did not let the criticism concern her. She was much more concerned about the erosion of traditional liberties that she felt the whole Watergate affair had brought out into the open. The American people had to be made aware of the situation, and she made them aware at every opportunity.

She had agonized over the impeachment question: “I have the same high regard for the office of the president as the majority of Americans. He is a figure who towers above all other figures in the world. Certainly no one could seriously consider forcing the president to leave office before his term expired. This feeling stayed with me a long time.” But the evidence had mounted, and reluctantly, she had concluded that impeachment was unavoidable if the Constitution was to be preserved. She had originally been “left out” of the Constitution, and yet she had seen how the provisions of the Constitution had been flexible enough eventually to include her. She had great reverence for the Constitution. Twice she had gone to the National Archives and stood in line with the other tourists to view that document. She had stared down at the yellowed parchment pages and realized anew how important it was to the country and to her. She thought about the Constitution a lot those days. Sometimes she mentioned it. When she referred sarcastically to the suspicious gaps in the tapes Nixon had surrendered, she said, “There are no gaps, there are no inexplicable ‘hums,’ in the Constitution of the United States.”

“We know that liberty is shaky because modern technology now has invested the government with the tools to invade private affairs through certain kinds of electronic mechanisms,” she said in a commencement address at Harvard University. “Thomas Jefferson warned us that the natural process of things is for liberty to yield and government to gain ground…. In recent years we have witnessed a willingness to accelerate the erosion of these guiding principles of American life. The erosion is very insidious because it didn’t happen all at once, but one step at a time. It happened under the guise of law and order. This erosion of civil liberties happened under the guise of the maintenance of national security; it happened…under the guise of executive privilege.”

By the middle of July, the House Judiciary Committee hearing of arguments and evidence on the impeachment of the president were about to conclude. All that remained were the final arguments by Special Prosecutor Leon Jaworski, Committee Counsel John Doar, and James D. St. Clair, the president’s own lawyer. On Thursday, July 18, St. Clair concluded the president’s impeachment defense, and he did so in surprising and alarming fashion.

The committee had previously subpoenaed the tape of a March 1973 conversation between the president and his former chief of staff, H. R. Haldeman. The White House had refused to surrender the tape, claiming it was not relevant. On July 18, 1974, St. Clair suddenly produced a 2 ½-page transcript of a portion of that taped conversation, claiming that it disproved the allegation that Nixon had authorized the payment of money to convicted Watergate burglars E. Howard Hunt and G. Gordon Liddy.

The committee was flabbergasted, and many were outraged at St. Clair’s audacity. How dare he wait until the “eleventh hour” to release a portion of a tape no one outside the White House had seen! How dare he present as evidence a 2 ½-page, edited transcript of a one-hour-and-twenty-four-minute conversation!

“I couldn’t believe it, I couldn’t believe it,” Barbara said, shaking her head. “It focuses on the utter contempt the president holds for the House of Representatives.”

Even some of the Republicans on the committee, who wanted to give the president the benefit of every doubt, were forced to reconsider their stand on impeachment. On the evening of Wednesday, July 24, the House Judiciary Committee began its televised debate on the impeachment of President Nixon. The thirty-eight members sat in two tiers of black leather chairs, the senior members on the top tier, the freshmen and other junior members on the lower level. Before each were piles of documents, for as many as twenty-two articles of impeachment had been proposed. These were some of them:

- Obstruction of justice in the Watergate coverup and approval of hush money and executive clemency for Watergate defendants.

- Nine charges of bribery, a specific impeachable offense under the Constitution.

- Unlawfully wiretapping citizens and creating the “plumbers” to undertake “covert activities without regard to the civil rights of citizens.”

- Misusing the Internal Revenue Service to harass political enemies.

- Violating the Constitution by receiving federal money in excess of compensation by law; specifically, money spent on his homes at San Clemente, California, and Key Biscayne, Florida.

- Committing fraud by underpaying his income tax between 1969 and 1973 by nearly $500,000.

- Contempt of Congress and the courts by refusing to comply with subpoenas for materials for the impeachment inquiry and Watergate trials.

- Concealing from the Congress facts concerning the existence and extent of bombing operations in Cambodia in the spring of 1969.

- Lying to Congress; specifically, his firing of Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox on October 20, 1973, “in abrogation of commitments to the United States Senate and to the people of the United States.” [The White House had promised that Cox would have complete independence.]

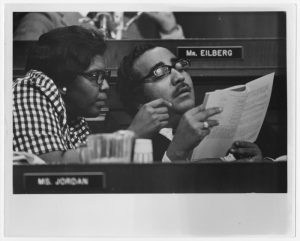

The committee had decided to consider three main articles, on lying, covering up, and abuse of executive power, with two minor articles on bombing operations in Cambodia and tax evasion. According to the rules they had set, each member of the panel would be permitted to debate them for fifteen minutes. The statements began with that of Chairman Peter Rodino and proceeded according to the arrangement of the panel, the top tier first. Having convened at 7:45 P.M., the committee adjourned at 10:40 that night; Barbara’s turn to speak would come the next day.

The committee reconvened at 10:10 A.M. Thursday, July 25. Methodically the speeches continued, and yet they did not drone on. The members of the committee were all highly aware of the historic significance of the hearings and of their own responsibility. Those who supported the president demanded facts—”specificity” became a catchword in the hearings. Those who were against the president gave those specifics, emphasizing different acts that they considered impeachable offenses according to their own viewpoints.

Barbara too could have listed those offenses she considered impeachable. Well-prepared as ever, she could recite dates, conversations, and so on, as well or better than any of her fellow members. But her speech would not be comprised of a string of meticulously researched quotes from the White House transcripts. Her speech would deal with tough interpretations of broad constitutional issues and the concept of due process. More than anything else, it would focus on her feeling that her Constitution was being subverted. At 8:15 P.M., the committee reconvened after its dinner recess. Charles B. Rangel, Democrat from New York and one of the three Blacks on the panel, spoke. Then Joseph Mariziti of New Jersey delivered his speech. Then Chairman Rodino said, “I recognize the gentlelady from Texas, Ms. Jordan, for the purpose of general debate, not to exceed a period of fifteen minutes.”

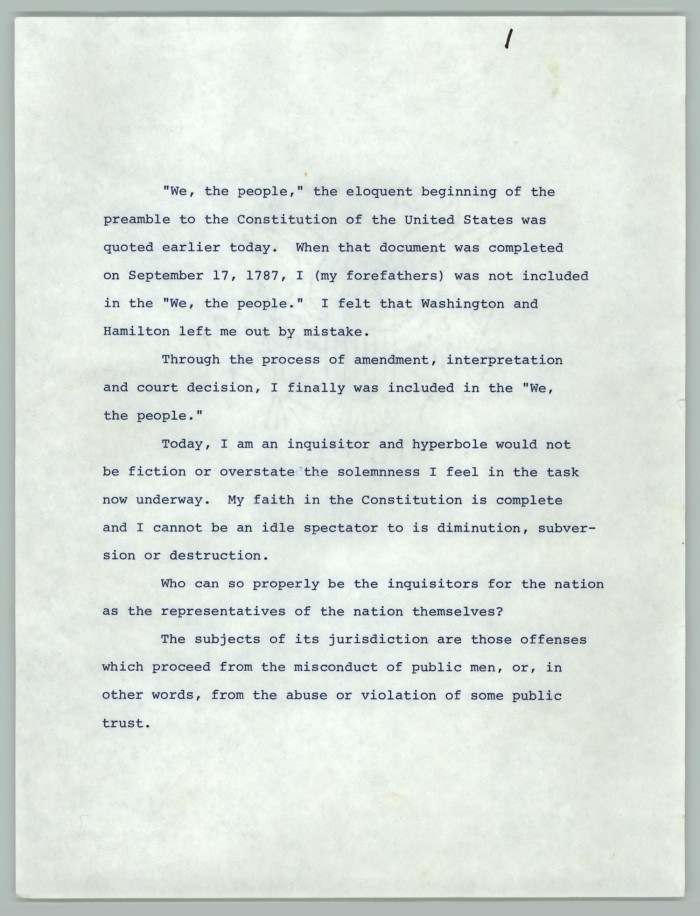

“Thank you, Mr. Chairman,” said Barbara. “Mr. Chairman, I join my colleague, Mr. Rangel, in thanking you for giving the junior members of this committee the glorious opportunity of sharing the pain of this inquiry. Mr. Chairman, you are a strong man and it has not been easy, but we have tried as best we can to give you as much assistance as possible. Earlier today we heard the beginning of the Preamble to the Constitution of the United States. ‘We, the people….'”

It was a long speech, taking up nearly the entire fifteen minutes allotted to her. But none of her listeners fidgeted. Her voice was hypnotic, her words powerful, and by the time she had said, early on, “My faith in the Constitution is whole, it is complete, it is total. I am not going to sit here and be an idle spectator to the diminution, the subversion, the destruction, of the Constitution,” she held her audience captive.

“I heard her on the radio,” said a friend, “and I thought it was God.”

She spoke of specific presidential acts, but she concentrated more on the precedents for impeachment as specified in the Constitution and as applied during the one earlier impeachment proceeding the country had seen, that of President Andrew Johnson. To her mind there was no question that the president’s acts warranted impeachment, for “… a president is impeachable if he attempts to subvert the Constitution. If the impeachment provision in the Constitution of the United States will not reach the offenses charged here, then perhaps that eighteenth-century Constitution should be abandoned to a twentieth-century paper shredder. Has the president committed offenses and planned and directed and acquiesced in a course of conduct which the Constitution will not tolerate? That is the question. We know that. We know the question. We should now forthwith proceed to answer the question. It is reason, and not passion, which must guide our deliberations, guide our debate, and guide our decision.”

With that speech Barbara Jordan became a national figure. Through the medium of television, millions had watched and heard her and had been overwhelmingly impressed. Blacks and women, in particular, were proud to claim her, but the appeal of her dignity, her articulateness, her concern, transcended racial and sexual lines. Her photograph was featured in both Time and Newsweek that week. The Washington Post carried the complete text of her speech the next morning on its editorial page, the only Judiciary Committee member’s speech to be carried in full.

On Thursday night, July 25, the House Judiciary Committee concluded the first round of its landmark impeachment debate, and it was almost certain that impeachment would be recommended. Of the thirty-eight members, nineteen had declared their belief that Nixon would be impeached and five other members had indicated pro-impeachment leanings.

The opening debate concluded, the committee now went into more intensive debate. Some of the Nixon supporters on the committee charged, as they had earlier, that they had yet to be shown where the president had specifically committed an impeachable offense. Ot

her members of the committee again tried to point out the specifics. The president’s supporters then complained that he had been denied due process of proper notice in the committee’s impeachment proceedings. By 6 P.M. Saturday, Barbara was visibly irritated. They had been conducting this intensive debate since Friday morning. At 8 P.M. Saturday evening, when the committee reconvened after dinner, she asked to speak. Her remarks were scathing:

“It apparently is very difficult for the committee to translate its views of the Constitution into the realities of the impeachment provisions. It is understandable that this committee would have procedural difficult

ies, because this is an unfamiliar and strange procedure. But some of the arguments which were offered earlier today by some members of this committee in my judgment are phantom arguments, bottomless arguments. Due process. If we have not afforded the president of the United States due process as we have proceeded through this impeachment inquiry, then there is no due process to be found anywhere…. Due process? Due process tripled. Due process quadrupled. We did that. The president knows the case which has been heard before this committee.”

On the evening of Saturday, July 27, the first article of impeachment came to a vote. The committee had heard evidence and debated on the matter for months; and while they were relieved to be voting at last, none of them, including the staunchest opponent of the president, was happy about wha

It had to be done. With the eyes of millions of Americans fixed upon the faces of the committee, the clerk called the roll:

Mr. Donohue—“Aye”

Mr. Brooks—“Aye”

Mr. Kastenmeir—“Aye”

On and on the voices droned. There were tears in the eyes and lumps in the throats, and votes cast in self-conscious voices.

Mr. Drinan—“Aye”

Mr. Rangel—“Aye”

Ms. Jordan—“Aye,” said Barbara in a low voice.

The vote was twenty-seven to eleven; Article I of the impeachment resolution had been adopted. Chairman Rodino recessed the committee until Monday morning. Spectators in the room went wild; reporters tried to corner the committee members. Barbara, like many others, wouldn’t talk at all as she hurried from the room. Later she said, “There were tears behind doors and off camera after the vote, from both men and women.”

By Wednesday, July 31, three articles of impeachment had been adopted by the committee, and two had not been. These last two, dealing with the bombing of Cambodia and the president’s questionable financial dealings, were supported by Barbara, but she was relatively satisfied with the three articles that had been adopted. She was more than satisfied with the way the committee had conducted its six-month probe. It had gained the respect of even the strongest Nixon supporters. And once again she, like many Americans across the country who had never really thought about it before, marveled at the strength and resiliency of the Constitution, which provided the framework under which the crisis that faced the nation could be handled in dignified and orderly fashion. The rule of law had been reaffirmed.

The vote of the House Judiciary Committee was just one step in the impeachment process. Its verdict would be reported out to the full House, which would then vote on whether or not to impeach the president. If the House did vote to impeach, a trial would be held in the Senate. It was quite possible Barbara would be a part of that trial, for there was speculation around Washington that Chairman Rodino would choose her as one of the five or six “managers” of the impeachment case in a Senate trial should the House approve impeachment.

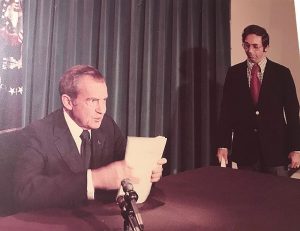

The matter never came to trial in the Senate, nor was it ever voted on by the full House. On the evening of Thursday, August 8, Richard M. Nixon resigned. Vice President Gerald Ford became president of the United States.

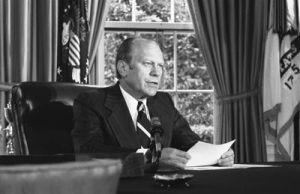

There seemed no rest for the House Judiciary Committee. Immediately they began confirmation hearings on President Ford’s choice of a new vice president. Barbara voted with the majority to confirm former Governor of New York Nelson A. Rockefeller. In her opinion, Rockefeller would provide balance to the administration, tempering Ford’s “classic conservatism.” She was beginning to think better of Ford now than she had when she had opposed his confirmation back in December of 1973. She was pleased with his first speech to the nation as president and gratified when, on August 21, he invited the Black Congressional Caucus to meet with him at the White House. She found him open to their suggestions and willing to work with them. “Even more important,” she said after the meeting, “he told us to just pick up the phone and call him. If he wasn’t in, the call would be returned. And we believed him.” Such an invitation would never have come from Richard Nixon.

Within a week Barbara had also gone to the White House as a female member of Congress, and shortly thereafter the president invited her to be part of a congressional delegation that would visit mainland China, the only freshman member on the trip.

During her entire time in Washington under the Nixon administration Barbara had been invited to the White House only twice.

But just as she was beginning to like Ford, he acted in a way that caused her to revert to her original opinion. While Barbara was in China, President Ford pardoned former President Nixon, making him immune from any criminal prosecution.

“I think President Ford acted prematurely in not letting the process of the administration of justice work before interspersing his presidential decision,” she said after she returned from the trip.

There were calls for an investigation of the pardon, and Barbara agreed that such an investigation should be held. But there was not enough support for the idea in Congress. The legislators, and many of their constituents, were tired of the whole matter. For over a year, the country had been subjected to one shock after another—John Dean’s testimony implicating the president in the Watergate coverup; the resignations of Haldeman and Ehrlichman; the resignation of Vice President Agnew; the firing of the first special prosecutor Archibald Cox; and the resignation of the attorney general, Elliot Richardson; the endless exposure of the president in his own lies—and there was a strong urge to return to some kind of normalcy. But suspicions about the pardon would linger, and now the case against Nixon could never be closed. The dangling threads of the Watergate scandal offended Barbara Jordan, along with other Americans who wished the Constitution had been followed to a final conclusion.

On the bright side, however, Barbara was much more confident now of the ability of the Congress to maintain its constitutionally authorized check on the executive branch. The House Judiciary Committee had done its job well, and there was no question that everyone involved in the impeachment process who had approached it seriously and sincerely had benefited from the experience. They had learned a lot; most important, perhaps, they had learned something about themselves. They had also benefited from it politically (only Charles Sandman of New Jersey, the most strident Nixon supporter on the House Judiciary Committee, would be hurt, losing his bid for re-election to the House as a near-direct result). Leon Jaworski, who had insisted on his independence as special prosecutor and pushed relentlessly for the Nixon tapes, was no longer a well-known Houston attorney but a nationally famous lawyer. In October he received the third annual award from the Barbara Jordan chapter of the Susan Anthony Society, because he had “made a maximum effort to sustain the American system of justice while it was under attack from many quarters.”

Clearly, however, no one had benefited more than freshman Congresswoman Barbara Jordan. She had captivated the press and a large segment of the American public. Washington’s Main Public Library offered videotapes of the Judiciary Committee’s televised hearings, as well as former President Nixon’s farewell address and President Ford’s swearing-in. A spokesman for the library said in October, “More people have requested Jordan than any other speaker.”

The conservative weekly magazine U.S. News & World Report called Barbara one of the Democratic Party’s “new luminaries” and quoted an unnamed observer as saying, “When the Democrats get around to nominating a black on their national ticket, they may well turn to Barbara Jordan.”

But for the time being, Barbara was content to return to Congress for a second term, and in November Houston’s 18th Congressional District re-elected her over her Republican and third-party opponents by a whopping 84.7 percent.