6 Triumphs and Tragedies

Texas was still no southwestern paradise for Black people. Discrimination continued in many areas, and being a state senator praised for her legislative work did not exclude Barbara Jordan from some of it. During her first term as a senator, she had been invited to speak before many groups—including the Nebraska legislature during a trip there to attend an N.A.A.C.P. convention—and had been honored by a variety of organizations. But when in early May the Austin Club, a private segregated club, decided to hold a party for the Houston delegation, they did so at a time when Barbara and Representative Curtis Graves, also from Houston, were conveniently “out of town.”

During the spring 1967 semester, T.S.U. had been the scene of student rioting in which a police officer died, many people were wounded, and 488 students were arrested. The facts of the affair were impossible to determine because of the wide variance in eyewitness accounts and the deep animosity between students and police. In both cases, Barbara reacted in a characteristically controlled way. Unlike Representative Graves, she did not publicly express any anger over not being invited to the Austin Club party. And at T.S.U., where she spoke at a Law Day convocation, she told the students that power was not gained by brick throwing but by using judgment and reason.

She was opening herself to a lot of criticism in doing so. In many parts of the country some Blacks were putting aside reason. In the summer of 1967, a spate of race rioting erupted in a number of cities. The rioters were primarily poor Blacks, for whom the recent voting rights and civil rights laws represented just so many pieces of paper. Such legislation had raised expectations but had not gotten poor Blacks better jobs or enabled them to earn more money as a result, so what good were they? Young Blacks who had previously participated in the demonstrations to bring about desegregation or who had belonged to S.N.C.C. had come to feel pessimistic and disillusioned and they supported the poor Blacks. Leaders like Barbara Jordan were in danger of being shunted aside, just like earlier over-accommodating Black leaders, only much more quickly. Despite pressures to become more militant, Barbara maintained her philosophy that a reasonable, realistic approach was most successful. Late in July she outlined her feelings in a speech before the Black National Bar Association:

“We live in a distraught present. Although we have had the courage to deplore it, we have failed to heal the gap between the middle-class Black lawyer and the Black slum dweller, who hates us almost as much as he hates Whitey….We must exchange the philosophy of excuses—what I am is beyond my control—for the philosophy of responsibility. We should tell the citizen that a man of liberty does not burn down the neighborhood store, then beg for his supper. We should tell him that a citizen of dignity does not wait for the world to give him anything.”

Her speech drew frequent applause and, when it was over, a standing ovation from the Black attorneys assembled to hear her. But from some other segments of the Black population, it drew accusations that she was “a sellout.” She tried not to let either reaction affect her. Her chief responsibility, after all, was to herself and what she thought was right.

In August, she donned her “lawyer’s hat” and filed suit against the Hughes Tool Company in Houston on behalf of two Black employees. The suit charged that the two Blacks had been denied the opportunity to advance beyond the lowest and most menial labor grades. In her speech before the National Bar Association, she had said the burden of change rested with Black lawyers. She was doing her part to bring about change.

In the fall she served as vice-chairman of the Democratic voter registration drive in Texas. She had told T.S.U. students the previous spring “if you don’t like the laws, then you withdraw your support of those [representatives] you have selected.” She backed up her words with actions, therefore she was respected, albeit grudgingly, even by the most militant Blacks.

The voter registration campaign, however, was not particularly successful. Former Mayor Lewis Cutrer was running against Mayor Louie Welch in the mayoralty campaign. The Negro Council of Organizations had endorsed Cutrer, but it never gave any reasons for its endorsement or why it was against Welch. Welch won the November 18th election. Only 38 percent of qualified Black voters had turned out to cast their ballots. Overall, only 37 percent of all qualified voters had actually voted—a large Black turnout could really have made a difference. But Blacks had not felt there was much choice between the two white candidates and so had taken the attitude, “What’s the use of voting for either?” That was not, Barbara sighed to herself, the way to make either Blacks or whites aware of the Black voters’ political clout. Perhaps they would do better in next year’s election.

But poor Blacks, particularly ghetto dwellers, were not especially inclined to greater participation in the political process. More and more they were beginning to “vote” with bricks and bottles, fed up with the gap between promises and actuality. In March 1968, Barbara was invited to participate in a conference on human relations held at the University of Texas Law School. The conference, which was attended by a number of southern Black leaders, discussed, among other things, the rising dissatisfaction in northern ghettos and the possibility that the disorders would reach the South and the Southwest. The participants also discussed the issue of racism. Charles Evers, who would later become mayor of Fayette, Mississippi, stated that in his opinion, racism was dead. In the discussions that followed, Barbara disagreed:

“Most Negroes have a little Black militancy swimming around in them,” she said, “and most white people have a little Ku Klux Klan swimming around in them. If we’d be honest with each other, we would discover we are all victims of [the] racism that is historically a part of this country.”

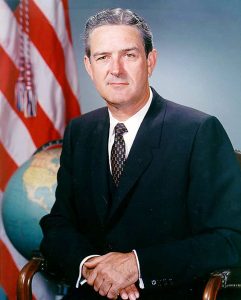

Barbara chaired the closing session of the conference, at which one of the panel members was a Houston attorney named Leon Jaworski. Jaworski had endeared himself to Blacks and poor whites in 1965 when he had spearheaded a drive for the establishment of a hospital district with power to levy taxes to support public hospitals. Barbara knew Jaworski; she had participated in various activities within the Houston legal community with him. They would become good friends.

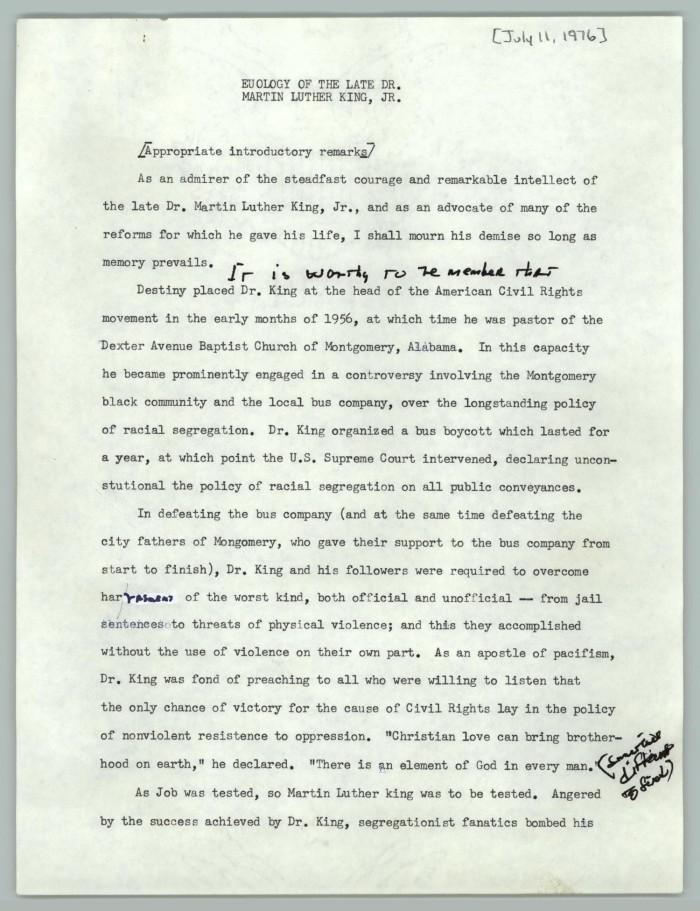

On April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated, and ghettos across the country erupted in violence. For Barbara, as for so many other Blacks, this tragedy, coming just five years after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, was almost too much to bear. What was happening to the United States? It seemed as if the country were dissolving in hatred and violence. Racial animosities, combined with the growing movement against the war in Vietnam, had created such a climate of national strife that it was easy to become dispirited. But Barbara continued to have faith in her country and its political process and to be patient as she waited for the inequities to be ameliorated.

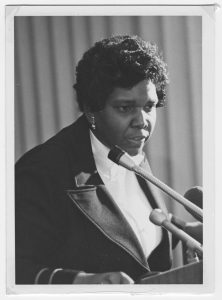

On April 14, memorial services honoring Dr. King were held in Houston as the official end of the period of mourning for the slain leader. Barbara was one of the organizers of the services. She invited Judge Bill Elliott and Mayor Louie Welch to attend: “We search for private and official commitment to the principles for which Dr. King lived and died,” she wrote to Welch. “We need your presence to affirm our faith in our future together and in the future of this country.”

She frequently found herself called upon to speak about the rising Black militancy and the future of race relations in the country. She grew tired of playing the role of spokeswoman for “moderate” Blacks. Yet at the same time she believed her voice of reason was needed, and so she tried to accept as many speaking invitations as she could.

“Black Power is a form of withdrawal from the fray, a form of accommodation,” she told a group of Texas media people in May. “The whole concept of Black Power acts as a shield of protection from the onslaughts of the society in which Negroes live in America. This concept is founded on fear—absolute, deep, abiding fear.

“The majority of Black people in this country, even those who shout the loudest, still believe in white America. The Negro in the main still has faith in your ability to change.”

Nineteen sixty-eight was an important election year for Barbara. Because she had drawn a two-year term in the Senate, she had to run for re-election to her seat. She hardly had to campaign—she ran unopposed. More important to her was the presidential election, in which, to her great sadness, Lyndon Baines Johnson would not be a candidate. As he had been popularly elected to only one term, in 1964, he was eligible to run again in 1968. But the war in Vietnam had destroyed him. Blacks, and some whites, realized that on domestic issues, especially in the area of civil rights, he was a great president. But in their violent antiwar feeling, many whites and a few Blacks forgot this aspect of the Johnson presidency. One day in the spring of 1968, Johnson had delivered an important policy speech on Vietnam. At the very end, to the surprise of everyone but himself and a few close advisers, he announced he would not seek re-election. Barbara was stunned. She feared that the end of the Johnson administration would signal the end of the major advances in civil rights legislation. She also had a more personal reason for missing President Johnson. As one of his protegees she had benefited from having a mentor in the White House. Being invited to functions at the White House had been something of a political plum for her, and just recently, in January, the president had appointed her a member of an elite national panel called the Commission on Income Maintenance Problems, whose other members were well-known economists and businessmen. For a young, ambitious politician it helped a great deal to have the president of the United States take a personal interest in her.

Barbara was a delegate to the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, which would choose the party’s presidential candidate. At such conventions it is often customary for a state delegation to vote for a so-called “favorite son” candidate—a state office holder, usually its governor—and thereby withhold its votes at first from one of the major candidates so as to be in a better position to bargain with him or her. Texas Governor John Connally had announced as a favorite son candidate from Texas, and accordingly the members of the Texas delegation were expected to vote for him. Connally was a conservative Democrat, not particularly well-liked by the liberals in his state. Yet in the interests of state delegation unity, most of the liberal delegates were expected to stand behind him, and under a regulation called “unit rule,” the delegation was supposed to vote as a unanimous bloc. But Barbara did not intend to do what was expected of her.

“I am going to follow the dictates of my conscience and my constituents,” she said. “They do not believe in the unit rule and neither do I. I will not act under it.”

“I will not vote for Connally under any circumstances,” she stated firmly.

Clearly Barbara was going to be a problem for the Texas delegation, and there was danger that her stand would disrupt the delegation if other liberals followed her example. That danger proved real. Four other liberal Democrats joined her in refusing to back Connally. Certainly the five mavericks presented little threat in terms of numbers—the delegation consisted of 104 members, but their impact on the delegation’s hoped-for solid front was considerable.

On Monday, August 26, Barbara was vindicated when the convention voted to discontinue the unit rule. Thus released from casting their votes as a bloc, other, less daring delegates abandoned their support of Connally.

“The defeat of the unit rule means the political leaders will not be able to deliver hand-picked delegations from senatorial districts and conventions to the state and national conventions,” Barbara commented. “It means the people will have to participate in the political process if they want to be delegates to the convention and have their viewpoints represented.”

But abolition of the unit rule was a small first step—too late and not enough to satisfy the individuals and groups who felt the Democratic Party did not adequately represent them. For days before the convention began, women; members of various minority groups; young people; draft resisters, poor people; and Vietnam veterans had converged upon Chicago in buses and private cars, walking and hitchhiking. Their primary concern was the Vietnam War, but they were also protesting their lack of representation among the predominantly middle-aged, white, male delegates. They chanted; they battled with police; they were beaten, arrested, and jailed. Inside, the convention seemed as if it were under siege; many of the delegates were more concerned, and rightly so, with what was going on outside than with the convention business. As it turned out, so was the country, and the bitter memory of Chicago in August 1968 would haunt the Democratic presidential campaign.

Vice-President Hubert H. Humphrey won the party’s nomination, but many of the delegates were unhappy about it. He was a compromise candidate. Conservative Democrats would have preferred a conservative; but since there was no viable conservative candidate, they had voted for Humphrey as a lesser evil than the two liberal candidates, George McGovern and Eugene McCarthy. Liberal Democrats had favored either McGovern or McCarthy and considered Humphrey an old-style politician out of touch with the times. All of the delegates at the convention could not help wondering what effect the presence of Robert F. Kennedy would have had on the outcome. The slain president’s younger brother, Kennedy had made a good showing in the primaries he had entered. He had represented a blend of liberalism, government experience (he had served as attorney general during his older brother’s administration), and political expertise that the other liberal candidates lacked. And he had the Kennedy name and charisma, an important quality that Humphrey lacked. Sadly, Robert Kennedy had been assassinated in June, one more victim of American unrest.

In the balloting at the convention, Governor John Connally displayed an excellent sense of timing in releasing the Texas delegates still pledged to him from voting for him as a favorite son. Their votes put Humphrey over the top, giving him more than the required number of delegate votes needed for the nomination. Barbara was satisfied with the Humphrey nomination. If he became president, he could be trusted to continue the social programs of the Kennedy and Johnson administrations—if he became president. But Hubert Humphrey was defeated by Richard M. Nixon in the 1968 presidential election. Across the country Blacks and many liberal whites groaned with dismay. Publicly, Barbara said little about the Republican victory—she was too shrewd a politician to alienate either the new president or his party. Yet privately, she was equally dismayed. Republicans were notorious for their lack of innovative social programs and their philosophy that massive government spending on domestic programs was bad for the country.

About the Texas elections she had mixed feelings. The state had a new governor. John Connally had served two terms and was thus ineligible to run for a third. His lieutenant governor, Preston Smith, had been elected. Barbara and Smith had a good relationship based on mutual respect and esteem. She would be able to support many of his programs. The new lieutenant governor and presiding officer of the Senate, Ben Barnes, was a moderate liberal. She would be able to work with him, and she would be able to do so for a full four-year term. Her biggest regret was that Senator Dorsey Hardeman had been defeated in his re-election bid. She would miss him.

There was one more election that November that interested and excited Barbara, not to mention several million other Black people. New York Assemblywoman Shirley Chisholm defeated civil rights veteran James Farmer to become the first Black woman in Congress. Barbara had to remind herself that New York was New York and Texas was Texas. But rapid changes were occurring in Texas politics, and Barbara’s drive to be “outstanding” did not necessarily have to end with the Texas Senate.