8 Hit On Broadway

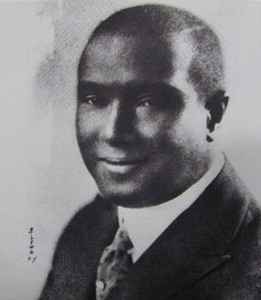

Herman Stark signed Bill Robinson and Cab Calloway to costar in the fall 1 937 show, the third to be presented at the club in its Broadway location. In order to get Robinson, Stark had to make special arrangements with Darryl F. Zanuck and Twentieth Century-Fox, with whom Robinson was under contract and for whom he had done The Littlest Rebel with Shirley Temple in 1936. Stark also agreed to pay Robinson $3,500 a week, the highest salary ever paid a Black entertainer in a Broadway production, and more money than had ever been received by any individual for a night-club appearance.

One week before the opening, however, Zanuck called Robinson to Hollywood to do Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm with Shirley Temple, which caused a bit of consternation at the Cotton Club. Because much of the show had been built around Robinson, the decision was made to delay the opening of the show for a couple of weeks, during which time the Nicholas Brothers could rehearse to replace Robinson.

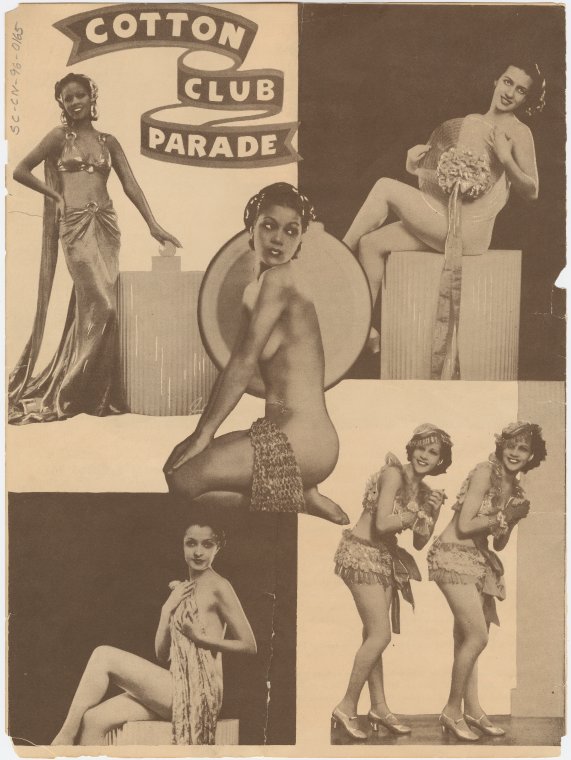

The show that finally opened suffered very little from Robinson’s absence. Large, lavish and fast-paced, it featured (in addition to Calloway and the Nicholas Brothers) Avis Andrews, Mae Johnson, Dynamite Hooker, the Three Choclateers, the Tramp Band, Will Vodery’s Jubileers, James Skelton, Freddy James, fifty showgirls and six Cotton Club Boys. Benny Davis and J. Fred Coots wrote the score of twelve songs, among them “Tall, Tan and Terrific,” “Nightfall in Louisiana” and ”I’m in the Mood for You.” Perhaps the best parts of the show were those that featured sixteen-year-old Harold Nicholas, who mastered in five days the routines abandoned by Robinson and received tumultuous applause on opening night and every succeeding night.

The traditional jungle effects were provided by Tip, Tap & Toe dancing on top of a large wooden drum, and by the sensuous dancing of Tondelayo, Princess Orelia and Engagi.

Mae Johnson did a hilariously funny takeoff on Mae West in the song ”I’m a Lady,” and Cab Calloway, as usual, was energetic enough to carry the entire show. In his funniest number, “Hi-De-Ho Romeo,” Calloway, dressed in doublets, played Romeo to Mae Johnson’s Juliet in swing time. The entire cast danced to a catchy and memorable number, “Harlem Bolero.”

Once again Stark had employed his winning formula, and as one columnist put it, the resulting revue proved that it was “greater than any individual star. ” Indeed, concerned that the loss of Robinson would result in a rather small attendance, Stark had at first presented only the after-dinner and after-theater shows. But with a hit show on his hands, after all, and throngs of crowds coming to the club, Stark announced that an extra revue would be offered every night at 2:30 A.M., featuring the entire cast.

Of all people, the master of ceremonies for the fall show of 1937, along with host Dan Healy, was Connie Immerman. Whatever else might have been said about the Cotton Club management, they never failed to help out “one of their own.”

When Bill Robinson returned to the Cotton Club, the Nicholas Brothers went back on the road, and the club closed for a few days in order to rehearse some new specialty acts and to recenter the show around Robinson. This meant lost revenues, of course, and Stark was privately unhappy with the changes the club and cast had been forced to go through as a result of Robinson’s sudden departure and subsequent return, the special agreement with Twentieth Century-Fox notwithstanding. Also, there was the matter of Robinson’s extraordinary salary.

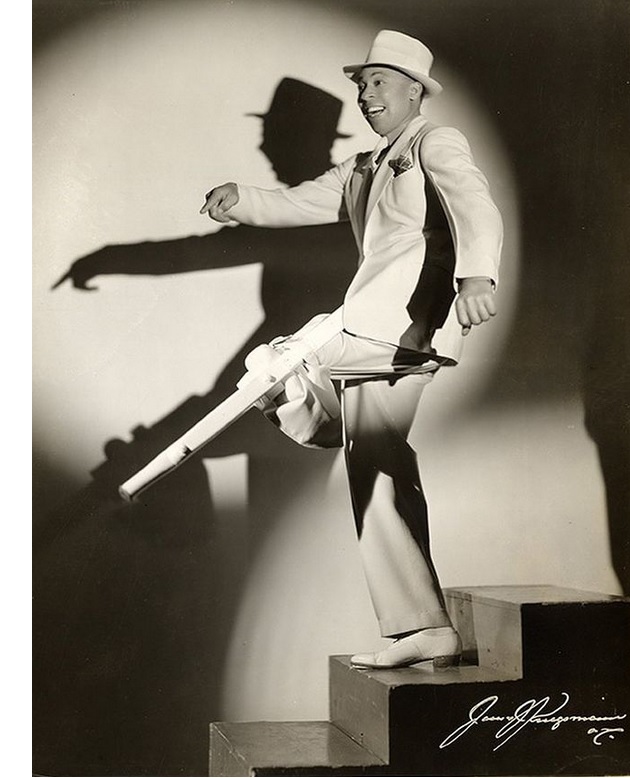

Robinson, however, was prepared to make a gesture in return, for the new version of the show would feature a new dance, the Bill Robinson Walk. It was the first dance he had created in over fifty years in show business that he considered expressive enough to carry his name. Needless to say, the Bill Robinson Walk was eagerly awaited.

The Cotton Club management, costumers and choreographers outdid themselves on the number. Fifty chorus girls appeared with Robinson in rubber Bojangles masks, and their movements echoed and counterpointed his own in a performance that brought many in the audience to their feet.

Thus, despite its late start and its mid-season changes, the latest Cotton Club Parade was highly successful among both columnists and audiences. Here and there, however, columnists expressed weariness with Stark’s winning formula. As one bylineless column said about the show:

. . . That it’s overboard on hoofing is a common failing of Negro floor shows, and is explained away by the obvious fact that any “serious” singing doesn’t seem to be accepted by the ofay trade; also a fast dancing pace is most consistently successful formula.

As a sidelight on this, one wonders what would be the result if they ever got away from the same routine of torrid terping; a coocher (usually backgrounded by a Congo motif); double-entendre lyrics (Ethel Waters started that vogue, and that takes in all the sundry switches on the ” Pool Table Papa” school of lyricizing); a “new” dance (Suzi-Q, truckin’, peckin’, etc.); and the cavalcade of standard Negro fol-de rol. But Herman Stark, impresario of the Cotton Club, both uptown and in midtown, has found from many years of experience just what pays, so what price glory? (1)

Duke Ellington and his orchestra returned to the Cotton Club to rehearse for the spring 1938 show. He had been named by Life magazine one of the “Twenty Most Prominent Negroes in the United States.” Soon (in late February) he was to be part of a “High-Low” concert at the Viennese Roof on the posh St. Regis, where he was the hit of the evening. By now he was what might be called a “polite success” in polite society, but he was a sensation among the Broadway crowd.

Ellington was looking forward to the new Cotton Club show, which would have even more supporting acts than the previous Broadway site shows and would be a full two hours in length. For the first time he would be writing the entire score, with the collaboration of fine lyricists, foremost among whom was Henry Nemo, one of the true characters of the New York entertainment world. At 250 pounds, he was literally a barrel of laughs. Singer, dancer, comedian, songwriter, he would entertain anywhere, anytime. Also, he was one of the few personalities who actually spoke the way the Broadway columnists wrote—that particular brand of fast-talk that incorporated such words as “socko,” “hoi polloi” and many more up-tempo words and phrases. His favorite self-description: “The Neem is on the Beam.”

Yet beneath the clown exterior beat a keenly sensitive heart—Nemo was capable of writing the most softly romantic lyrics. “‘Tis Autumn” and “Don’t Take Your Love from Me” are Nemo songs. Ellington, who was trying his hand at love ballads for the first time, and Nemo together produced two memorable torch songs, “If You Were in My Place” and “I Let a Song Go Out of My Heart,” which proved to be among the three masterpieces of the show.

The latter number almost did not get written. Working with Nemo and other lyricists, first on one tune, then on another, back and forth, seeing song after song materialize, Ellington was almost taken by surprise when he realized that twelve tunes had been completed. The others were satisfied with the output, but Ellington was not. Extremely superstitious, he decided that a show with twelve numbers was unlucky. Enlisting Nemo’s help, he composed the thirteenth, “I Let a Song Go Out of My Heart.”

Rehearsals for the show gave Ellington the opportunity to renew his acquaintance with Will Vodery, with whom he had worked in Florenz Ziegfeld’s Show Girl after leaving the Cotton Club in 1930. George Gershwin had written the score for Show Girl, and while the show did not give Ellington any opportunities to exhibit his own composing talents, it had given both him and his orchestra much-needed experience. Ellington learned much from Vodery, who was then Ziegfeld’s arranger. Ellington had been exposed to little traditional music. Vodery had assimilated the classical experience and translated it into a successful comedy, pit-band style. It was much easier for Ellington to understand the harmonies and colorations of classical music in this translated form, and Ellington often credited Vodery with teaching him orchestration. During the late winter and early spring of 1938, while rehearsing for the new Cotton Club show, Ellington and Vodery reminisced a lot about Show Girl and the Ziegfeld days.

The show opened at midnight on Thursday, March 9, 1938, and it was yet another hit for Herman Stark. In addition to the two popular songs written with Nemo, Ellington’s “Braggin’ in Brass” brought the audience to its feet, and “A Lesson in C” satisfied the patrons’ desire for a bit of symphonic jazz. The “swingtime Romeo and Juliet” act of the previous show had been such a success that Mae Johnson continued it without Cab Calloway. Her hilarious Mae West impersonation in the act occasioned the first night club appearance since achieving movie stardom of the real Mae West, who was guest of honor at one of the club’s Sunday “celebrity nights.” Anise and Aland, Aida Ward, the Four Step Brothers and the Three Choclateers did their specialties. The Peters Sisters, who had appeared in numerous motion pictures, made their New York night-club debut in the show. Weighing 300 pounds each, they commandeered the stage with their singing and dancing in “Swingtime in Honolulu” and “Posin’.” Another two-man dancing team was introduced—Rufus, seven, and Richard, five.

Among the most popular “specialty act” performers was Peg-Leg Bates, who was a star before he arrived at the Cotton Club, although his stint there certainly did not hurt his career. Peg-Leg, whose real name is Clayton, got his name because he actually has a wooden leg. In 1918, at the age of ten, he was working in a cotton mill in Greenville, South Carolina. One night the little boy slid into the auger of a cottonseed mill and lost his left leg. While most people would have considered such an accident tragic, Bates recalls that night as the luckiest of his life. “Hadn’t been for that,” he says, “I’d be on a cotton farm this minute, plowing my crop.” (2)

A small boy with only one leg is open to much sympathy and a great deal of ridicule, neither of which set very well with Clayton Bates. He got his uncle to make him a peg leg and he practiced on it, in the woods by himself, until he could walk and run five miles at a stretch.

“Then one night,” Bates recalls, “my uncle was in the kitchen at home. He had just come back from the war, and he was in good spirits. He began to dance on the kitchen floor. I got up and imitated him. I found I could make a beat and match it with my peg. I got ambitious.” (3)

Soon he was dancing in the amateur shows at the Liberty, a Black theater in Greenville, where he won prize after prize. When a stock show came through town, he ran away with it. He played across the South, with one company after another, sometimes as an individual act and sometimes as part of a team. He arrived in New York in 1928 to play a week at the Lafayette Theatre in Harlem, and he attracted such attention that Lew Leslie signed him for Blackbirds of 1928. After accompanying the show to Paris, he returned to New York to play at the Paradise (downtown) and Connie’s Inn. Two trips to London and he was back in New York, stomping out on the Cotton Club stage and singing, “I’m Peg-Leg Bates, that one-legged dancing fool.” He now owned “thirteen peg-legs, one to fit every suit, all colors . . . ”

In the spring of 1 938 Cotton Club show he danced to “Slappin’ Seventh Avenue with the Sole of My Shoe,” and audience applause brought him back on the stage more than any other performer.

After Bates’s number, the chorus danced to “Carnival in Caroline,” and in the grand finale the company introduced yet another new dance, the skrontch, which, it was said, had been done a century earlier in Kentucky. While it was not as exciting as earlier dances introduced at the club, its “catchy” name would ensure it long life. Later, in recording, the name would be made a little less catchy, changed to “the scrounch,” for obvious reasons.

The names of Ellington’s tunes were quite frequently questioned, or changed for mass consumption, although sometimes those that were questioned need not have been and those that were not questioned should have been. April 29, 1938, marked Ellington’s thirty-ninth birthday and approximately his tenth year in the music business, and the Cotton Club celebrated with a matinee party and a special broadcast to England through the BBC. As was the usual procedure, the numbers for the broadcast were submitted to the censor board for clearance and were passed. But just before the scheduled broadcast, a worried assistant called from the station to question the titles of two numbers, “Hip Chick” and “Dinah’s in a Jam.” Did the former have anything to do with hips? And it was hoped that the latter title did not refer to pregnancy. Ned E. Williams, publicity man for Ellington’s agent Irving Mills, assured both the assistant and the now-worried censor board that they had nothing to worry about, but he could not allay their fears. As both numbers were instrumentals, it was decided to give them tamer titles for the broadcast. Interestingly enough, the radio censors never questioned the meanings of such titles as “T. T. on Toast,” “Warm Valley,” and others.

Before the opening of the fall 1938 show, the Cotton Club was redecorated. Julian Harrison, former scenic designer for Cecil B. DeMille and who had been associated with the club for some years, supervised the decorations, which included the redesigning of the bar and entrance lounge and the installation of murals depicting the evolution of swing.

By this time, swing had completely captured the public taste, and the major white swing bands overshadowed all but the most successful Black bands such as Ellington’s and Calloway’s. Aware of the popularity of swing and always quick to capitalize on a trend, the club’s management commissioned the murals. Among the bandleaders who appeared there were Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey, Gene Krupa and Larry Clinton, but in the Cotton Club murals their likenesses were given what surely would have been called, in those days, a “sepian twist.” They were all depicted in blackface.

The club also elaborated its service by installing for the first time a maitre d’ in the person of one Robert Collins.

Cab Calloway was brought back for the show; this alternation of Ellington’s and Calloway’s bands was becoming something of a tradition. Calloway shared top billing with the Nicholas Brothers, and together they presided over the usually talent-packed roster of performers including the Berry Brothers, Mae Johnson, Whyte’s Lindy Hoppers, the Cotton Club Boys, and June Richmond. W. C. Handy, famous for “St. Louis Blues,” would appear from time to time to play trumpet or cornet in the finale, but he did not play every show. While still active and energetic, he was getting on in years. On November 20 the club held a gala celebration to mark his sixty-fifth birthday.

The show opened on September 28, the curtain lifting to reveal a plantation setting—”Col. Cosgrove’s Plantation” said the identifying sign—with a decidedly thirties air. Other signs prominently displayed on either side of the stage read: MY BOSS STILL HAS THE FIRST DAME HE EVER MADE! and SILK UNDERWEAR DON’T MAKE A LADY. However, there was neither a plantation nor any other unifying theme for the show, which was a potpourri of fast-paced entertainment, heavy on dancing and light on comedy.

Benny Davis and J. Fred Coots had written the score, which included such songs as “I’ve Got a Heart Full of Rhythm” and “Scarlet O’Hara from Seventh Avenue. ” The latter, sung by Mae Johnson, poked fun at David O. Selznick and Clark Gable in its ribald lyrics, and was one of the big hits of the show.

Jigsaw Jackson did an acrobatic-contortionistic dance, Estrafita shimmied while Mae Johnson sang “Congo Conga,” and Cab Calloway led the number “A Lesson in Jive.” A new dance, the boogie woogie, was introduced, and because Cuban dancing was all the rage, the club featured, in addition to the “Congo Conga” number, a new dance band, Toccares’ Orchestra, billed as from Cuba.

Two “new acts” were presented in the show. Of the two, the more successful was Sister Rosetta Tharpe, who presented the first Holy Roller-gospel numbers ever featured at the club. Already fairly well established as a folk celebrity, Sister Tharpe had risen to prominence on the crest of the popular gospel-music wave. Long considered particular, and peculiar, to Southern churches, gospel had been introduced to Northern Blacks by Mahalia Jackson and others in the twenties. Northern Black ministers and other bourgeois Blacks considered gospel a dirty word, but despite their objections the style had flourished. It had not taken long for clever entrepreneurs to see the commercial possibilities in gospel, and a split occurred among gospel singers. On one side were those like Mahalia Jackson, who believed that gospel was God’s music and that to turn it into a show for night club drinkers was to mock God ‘s work. On the other side were those like Clara Ward who believed there was a place for “pop gospel”; good sentiments were the same whether expressed in church or cabaret, and if people were willing to pay to hear them, so much the better. Rosetta Tharpe was of the latter opinion, although she was a good friend of Mahalia Jackson’s. At the Cotton Club, Sister Tharpe gave lively interpretations of “Hallelujah Brown,” “Rock Me” and “The Preacher,” and her guitar playing alone made a trip to the club to see the show well worth it.

The other “new act,” the Dandridge Sisters, had arrived in New York after playing bit parts in several Hollywood movies—Going Places, Snow Gets in Your Eyes and It Can’t Last Forever. Dorothy and Vivian Dandridge and the non-sister, Etta, were very young; Dorothy was only fourteen. In their style and in the type of songs they sang they were much like the Andrews Sisters. They were also quite naive, having been brought up in the West and having a very protective agent, Joe Glaser. Dorothy Dandridge recalled when they sang their first number at a Cotton Club rehearsal:

The entire Cotton Club company was at hand during the rehearsal as Vivian, Etta, and I whipped through a number we believed was appropriate. It was all about,

“The midnight train came whoosin through,

The merrymakers were in full swing,

And everybody started to sing,

Da-da-de-um-dum-do.”

The whole company broke into a fit of laughter that embarrassed us and cut us short. We figured we were finished. (4)

They were wrong, of course. They hadn’t been brought all the way from the West Coast merely to audition. Their youth and their light-skinned good looks were what Stark was after. In the show they sang “A-Tisket A-Tasket” and “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” and were featured with Calloway and June Richmond in “Madly in Love.” Columnists called their style “refreshingly unique,” and, one writer remarked, “with the middle femme especially strong vocally.”

The “middle femme,” Dorothy, was two years younger than Lena Horne had been when she joined the Cotton Club, and she was equally in awe of the older chorus girls, intrigued by their lives. She recalled:

They shelled out money on the perfume man and the lingerie man and the other special salesmen who came backstage. How could they afford all this? I wasn’t that young; I suspected that not all of their purchases were made on a chorus girl’s income. Between shows their boyfriends came around. Limousines rolled up in back of the Club as if it was a bus terminal. (5)

Soon Dorothy was to have a boyfriend of her own—Harold Nicholas. “I saw Harold on the day I arrived at the Club,” she later recalled. “We were backstage, making ready to put on our singing act for Cab Calloway and his men. Harold was on stage with his brother, Fayard, and they were doing a dance turn. As Harold tapped he was eyeing me. I had heard of him, had seen photos of him, and I knew that he and his brother were already famous and money-making entertainers. . . I learned that they had a big car and a chauffeur, and that their mother, who traveled with them, had a mink coat. All of which was impressive to a fourteen-year-old suddenly in the company of big-timers.” (6)

Equally impressive was the seventeen-year-old Harold’s talent. In the fall 1938 Cotton Club show he was revealed as a particularly creative performer, reminiscent in many ways of a young Bill Robinson. Columnists singled him out, something they had not done before; and when he, in turn, singled out Dorothy, she was excited and flattered.

It did not take long for word of the romance to get around behind the scenes at the Cotton Club, and Dorothy noticed that the chorus girls gave her more than the usual number of worried looks. They were quite protective of her in general, ceasing their talk about men, for example, when she walked by. After she and Harold began seeing each other, she suspected they were talking about her, and she knew it when they hushed each other as she passed. Finally, one day, Mae Johnson exclaimed to the others, “Oh, don’t be silly. Dotty’s got to grow up. She might as well know.” (7)

Dorothy Dandridge wanted to know. “They said that one girl who had been going with Harold had been so badly upset by a breakoff between them that she had had a nervous breakdown. I heard that Harold had been out with many of the girls in the company.” (8)

Harold, Dorothy learned, had “been down the line,” as the other girls put it. While only three years older than she, he was a decade beyond her in worldliness. She was warned to stay away from him, that he would get her into trouble. But Dorothy loved Harold, and Harold presented to her a very different side than he had shown to the other girls at the club whom he had dated. “It was a puritanical, idyllic relationship,” Dorothy later recalled, “a four-year romance replete with talk-talk, hot dogs, movies, chitlins, boxes of candy, long walks, hand-holding, flowers. It was corny as the stalks in Iowa; and our sex was limited to kissing and getting hot, but for me it was fun.”

A few years later Harold Nicholas became Dorothy Dandridge’s first husband, but the marriage, like many in show business, was a brief and unhappy one.