1 Harlem Comes of Age

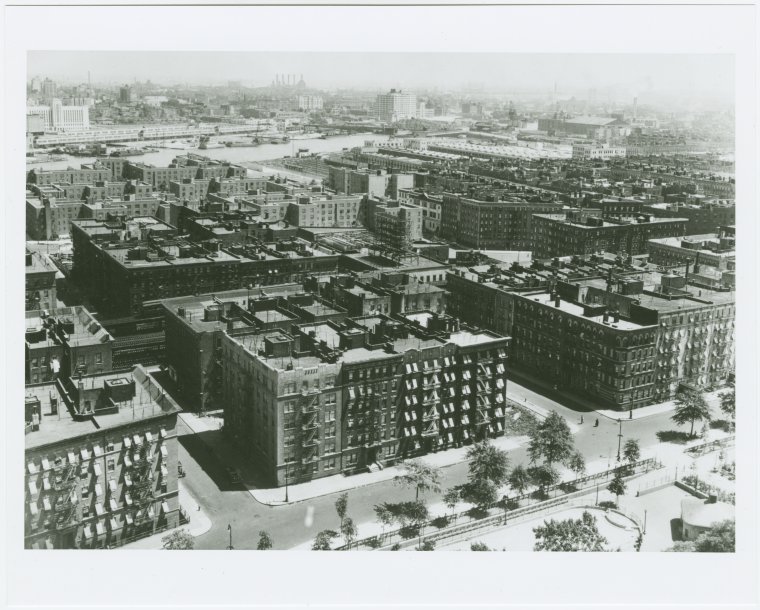

A major change in the living patterns of American Blacks took place in the years surrounding World War I. Formerly, even in the Northern cities, Blacks had lived in homogeneous but widely scattered locations. In New York City some Negro districts such as the Tenderloin and San Juan Hill were clearly identifiable and their names immediately recognized. Yet none was more than a few blocks in area. Prior to World War I, small Black residential enclaves could be found throughout the city. Thirty-seventh and Fifty-eighth streets, between Eighth and Ninth avenues, were Negro blocks. All the blocks surrounding them were white. There were even Negro blocks in Harlem, which the eighteen-eighties and nineties was fast developing into a place of exclusive residence, the first affluent white suburb.

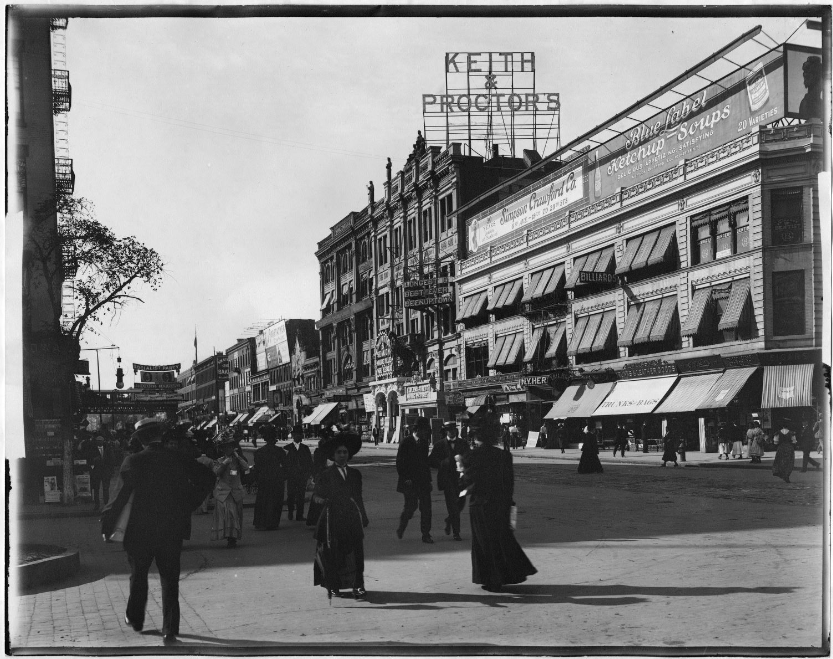

White upper-middle-class New Yorkers viewed Harlem with great expectations, chiefly for two reasons. The first was technological. Between 1878 and 1881 Manhattan’s three elevated railroad lines were extended to 129th Street, and plans for extension farther north were on the books. Previously Harlem’s major drawback had been its distance from the city’s core; the elevateds would make it accessible. The other factor was immigration. Thousands of Europeans were descending on the city, and in 1880 the population passed the one-million mark. The immigrants settled and established ethnic enclaves, and older white residents fled. As Harlem’s transportation facilities improved, so did its residential prospects, and land speculators quickly moved in to make their fortunes. Town houses and exclusive apartment houses went up as fast as the land on which to put them could be purchased.

Meanwhile, as Harlem was being prepared to welcome upper-class New Yorkers, the city’s Black population mushroomed. The advance guard of the “Great Migration” began to arrive in the large Northern urban centers about 1890, and in New York the Negro population would nearly triple in the next twenty years. The new arrivals crowded into the small and scattered Black sections and pushed their boundaries outward. Early on, it was clear to any thoughtful observer of the urban scene that a large and homogenous Black residential section would eventually develop. But few could have foreseen that the section would be Harlem.

The bottom fell out of the Harlem real estate market in 1904–1905. Too late, speculators realized that too many buildings had been erected too fast, that the price of land and the cost of houses had been inflated way out of proportion to their true value. In their frenzy to recoup their losses, speculators and realtors turned, directly and indirectly, to the Negro. Some opened their buildings to Black tenants, who were traditionally charged higher rents than other ethnic groups. Others used the threat of renting to Blacks to force white neighbors to purchase vacant buildings at inflated prices. Many white residents of Harlem were willing to pay any price to keep out Blacks, and nearly all were against having Negro neighbors.

But the various white groups were never able to muster a united front, and Blacks began to move into Harlem in large numbers, many occupying apartment houses that had never been previously rented. Harlem was a “decent neighborhood,” and for many of the new Black residents it was the first time they had ever been able to live in one.

Black churches moved uptown from the older Negro sections, following their congregations, and by the early nineteen-twenties practically every major Black institution had moved from its downtown location to Harlem. While similar developments had occurred in other large cities like Chicago and Philadelphia, Harlem was unique among Norther urban Black enclaves. Not only was it the only Black community to form in an exclusive residential section but also it was the largest Black community in the United States.

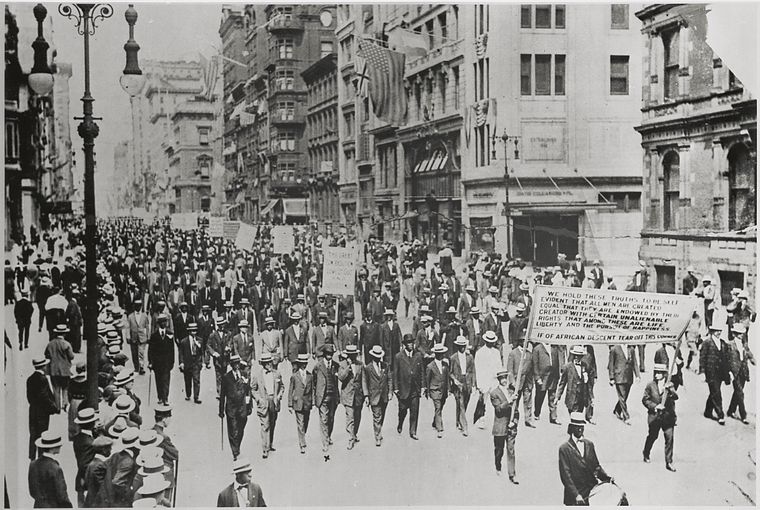

The very name Harlem took on magical connotations to American Blacks. Langston Hughes wrote of emerging from the subway at 135th Street and Lenox Avenue and exulting at the sight of so many fellow Blacks; he wanted to shake hands with all of them. Harlem became the largest Black audience in the country, ripe for Marcus Garvey and his Back to Africa movements and for A. Philip Randolph and his labor-organizing activities. Harlem, too, represented money, as did New York in general.

The Blacks who moved into Harlem prior to the war were monied people, able to afford the high rents charged in the new buildings. Like most upper-middle-class Americans, they formed their own bridge clubs and social clubs, held cocktail parties and exclusive dances, and supported the rapidly growing cultural life of Harlem. Later, working-class Blacks were able to move into the area distinguished by spanking-new buildings and broad tree-lined avenues. During the war, jobs were numerous in the munitions and war-materials factories, and Black workers were actively recruited by Northern industries. (In this case, for once, European immigrants helped American Blacks, although indirectly. When war broke out in Europe, thousands of immigrants returned to fight for their native lands. New immigration virtually ceased, leaving an unprecedented shortage of labor and a new demand for Black workers.)

War-inflated wages enabled many Blacks to pay the exorbitant Harlem rents and still save, and with their savings they invested in Harlem property. All classes bought, and it was not unusual for a Black woman who made her living by taking in laundry to purchase a house. Among the best-known seekers of this ultimate American dream was Mrs. Mary Dean, known as “Pig Foot Mary” for the Southern delicacy she vended, pushcart style, in the streets of Harlem; she made a fortune in real estate dealings.

During and after the war, fraternal/social organizations increased rapidly in Harlem, and lodge meetings and lodge halls abounded. In the warm months hardly a Sunday passed when one lodge or another did not celebrate a founding, or honor a decreased member, or simply turn out to represent its standing in the community. Other service enterprises, such as funeral parlors, real estate offices, laundries, were opened by Blacks to serve the Harlem community.

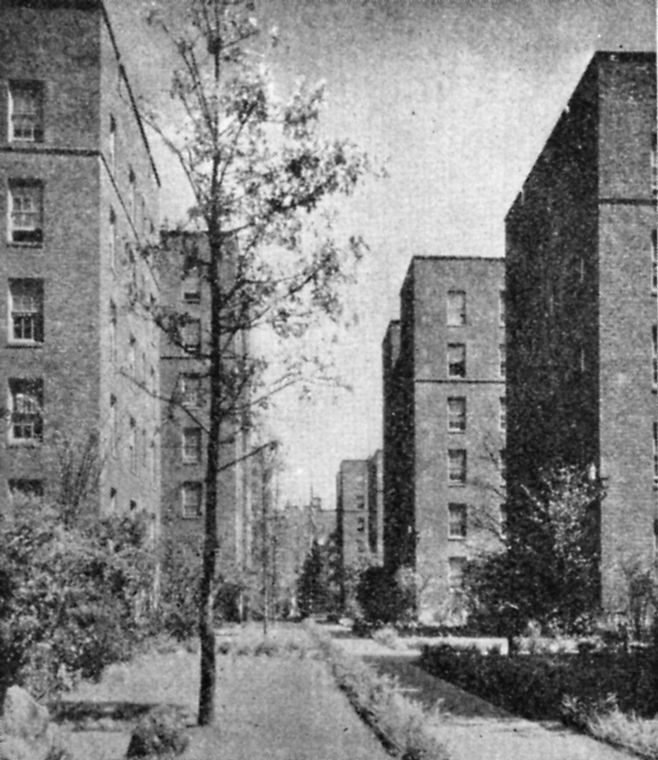

Simultaneously the seamy side of Harlem life developed. Legitimate service enterprises were matched by numbers operations, houses of prostitution, dope peddlers. And despite wartime and postwar prosperity, a sizable poor class was growing whose wages could not meet the exorbitant rents, who partitioned off their large apartments and rented rooms and half-rooms to newcomers. By the early twenties, overcrowding was already turning parts of Harlem into slums.

Yet Harlem in the early twenties was chiefly a prosperous Black community, its inhabitants proud of their neighborhoods, aware of their strength in numbers. Harlem was not a section that one “went out to”; it was not separated from the rest of the city the way most Negro sections were in other cities. It was neither a slum nor a quarter, but a well-lit, well-paved, well-kept area linked to downtown Manhattan by major avenues and means of public transportation. It was new and growing, and for outsiders it meant opportunity.

Not only laborers came to seek their fortune in Harlem. Those with talent and creativity, and those with pretensions to talent and creativity, were drawn to the place where the widest Black audience could be reached, where they could live in a community inhabited almost entirely by fellow Blacks. And the more self-confident and articulate Blacks came to Harlem, the more attractive it became for still others.

They came—Fritz Pollard, All-American halfback, who sold Negro stock to prosperous Black physicians; Paul Robeson, All-American end, preparing to go to law school, unaware that the stage would intervene; the songwriting team of Creamer and Layton, who had written “After You’ve Gone” and twelve more songs, and who would later write “Strut, Miss Lizzie”; singers Ethel Waters and Florence Mills, trying to launch their careers; writers like Claude McKay and James Weldon Johnson and Langston Hughes; Preacher Harry Bragg, Harvard Jimmie MacLendon, Bert Williams; a host of other entrepreneurs, artists, writers, actors, singers, all seeking their fortune and each other.

In greater numbers still came the musicians, a large influx of jazz musicians, especially blues players from the South. The dance craze that swept the country between 1914 and 1918 had created a need for violinists and drummers when previously a single pianist had been sufficient. And after the war, small groups, including horns began to arrive, attracted by stories that both work and money were abundant in New York.

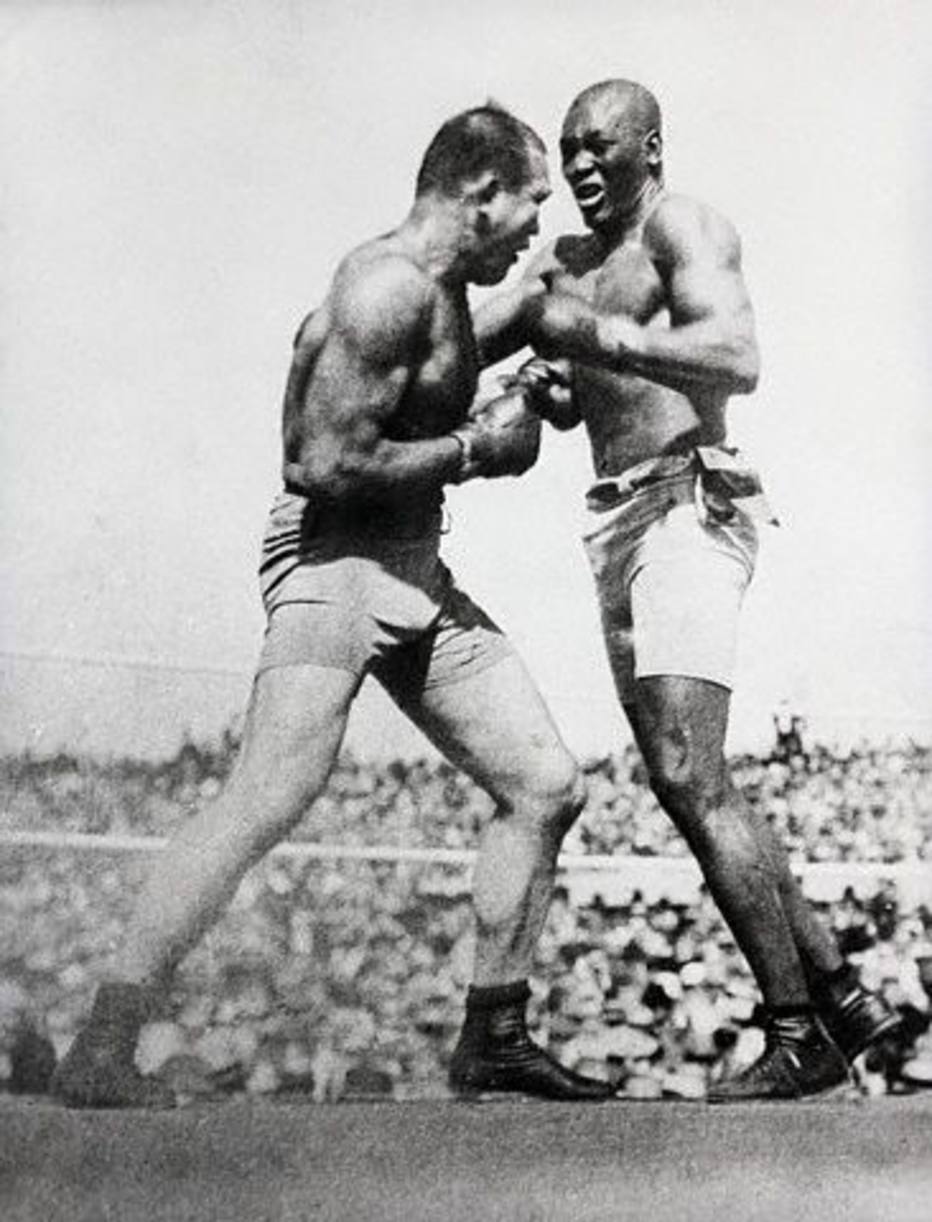

There was plenty of work for these musicians in Harlem, for as Black Manhattanites had moved north, so too had the rathskellers, following the trade. These primarily white-owned establishments, which took their name from the German word meaning cellar beer garden, had been localized in the Forties bordering on Sixth Avenue in the Hell’s Kitchen district, site of one of the largest concentrations of Black Manhattanites. Following the 1910 victory of Black heavyweight boxer Jack Johnson over “Great White Hope” Jim Jeffries, however, outraged whites rioted, smashing, among other establishments in the “Negro Section,” the rathskellers. Rather than reopen at their old locations, many rathskeller owners chose to relocate in the fast-growing residential area of Harlem.

The new Harlem establishments were not commonly located in cellars, and the term rathskeller fell into disuse. Only two of these transplanted nightspots were owned by Blacks; the rest were owned by Irish: Connors’ (operated by John Connors, who, unlike the others, had moved to Harlem from Brooklyn, where he had operated the Royal Cafe), at 135th Street near Lenox; Edmond’s, on Fifth Avenue at 130th Street; LeRoy’s, at 135th Street and Fifth Avenue.

They were smoke-misty rooms filled with conversation and laughter, flowing with bad booze. Some were furnished with oddly assorted chairs and white porcelain tables, others with linen-covered tables and velvet-smooth floors. In many, the entertainment consisted of one piano and one female blues singer, her hoarse voice rising vainly over the babble. Larger establishments usually featured a small band or combo, whose size often depended on the volume and economic status of the audience. The common arrangement between musicians and club management was to place a bowl or cigar box in a central location, and to divide its contents equally among the musicians at the end of the evening. Often the accessibility of the box or bowl caused difficulties. Willie “The Lion” Smith played LeRoy’s in those days. He recalls having to install a mirror on top of the piano in order to keep an eye on the cigar box and the singers, musicians and waiters, who were prone to dip into the till for themselves.

The clientele of these nightspots was chiefly Black, although in some it was not uncommon to find, over in a corner, a group of whites huddling and grinning and believing they were having a thoroughly wild time. Slumming, it was called. The Black patrons paid little attention to them.

In other Harlem cabarets, whites were rarely seen except as guests of Blacks, and were often unwelcome even on that basis.

The following incident, related by a writer of the day, was typical of the Blacks’ attitude:

There was a public dance in the old Palace Casino one night. Two white fellows walked in the place and commenced dancing with some of the ladies of color. Immediately there was a young riot. The ladies and gentlemen stormed the manager’s office, and threatened all kinds of wild happenings if the white intruders were not ejected. The manager ordered the music stopped, and with a great show of race patriotism, ordered the two men to go downtown and dance with their white women and stop breaking up his business. I have seen this duplicated at the Renaissance [Casino] and other places in a lesser degree. (1)

Most white New Yorkers south of the city’s “Mason-Dixon Line,” 110th Street, remained relatively unaware of what was going on in Harlem. Certainly most had heard of Marcus Garvey, but he was considered a comical figure by the white downtowners. A. Philip Randolph had made little headway and indeed would not make any for another ten years. The talents of an Ethel Waters or a Noble Sissie or a Eubie Blake were unknown, and white publishers had not as yet taken much interest in Black books. Comparatively few whites were interested in Harlem, and fewer still were aware that Harlem was beginning to experience a period of great creativity, born of the coming together of a variety of people and styles. Black writers and poets from across the country met and shared their dreams and their attitudes about being Black in America. They talked for hours in small dark cabarets and crowded apartments, reading their latest work to fellow writers, helping each other find housing, food, jobs, encouraging each other. New writing styles and new ways of looking at themselves and the world developed from this interchange.

Among the most notable groups were the young Black poets, who seemed to emerge simultaneously about five or six years after the war. James Weldon Johnson, writing in 1930, identified some fifteen poets as writing “verse of distinction” in the early twenties, four fifths of them residing either in New York or Washington, D. C. In 1922 Johnson published The Book of American Negro Poetry, an anthology of poetry that included works by many of these younger writers. Black fiction, too, was suddenly imbued with new life. W. E. B. Du Bois’ novel The Quest of the Silver Fleece and James Weldon Johnson’s The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man were published early in the decade, and in 1923 came Jean Toomer’s Cane. Black writers exhibited a new boldness in treating the conditions of Negro life. The following year Walter White wrote of the Black existence in a small Southern town in The Fire in the Flint, and Jessie Fauset applied the same techniques of realism in writing about Negro life in a Northern city in There Is Confusion.

Cash prizes for literary work established around 1924 by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the New York Urban League provided further stimuli to the Harlem literary movement. They drew young writers to New York, as did the various radical literary magazines and newspapers, some new, some established but imbued with fresh vigor. The Messenger, Challenge, the Voice, the Crusader, the Emancipator, the Negro World provided an unprecedented forum for the works of young Black writers.

Negro theater experienced a different evolution. Of all the arts, it enjoyed the greatest strength and popularity in the war years. Between 1910 and 1917 the first true Black theater in New York grew up in Harlem—a theater in which Black performers played to almost totally Black audiences. Supported chiefly by the monied bourgeois class, two major Harlem theaters, the Lafayette and the Lincoln, developed excellent stock companies. Small theater groups abounded. It was an era of great creativity, spurred by isolation, for the years when Black theater was at its height in Harlem were also years during which Black shows were essentially banned from Broadway. In the early twenties, while the other arts were incubating in Harlem, Black theater was being reintroduced downtown and would eventually lead to the birth of the popular Harlem Renaissance.

Meanwhile a period of creativity similar to that in the literary area was occurring in the area of Black music, and out of it would come the first New York jazz style. Jazz, as an identifiable style, was relatively new. A product of slave songs containing African elements, Black spirituals, urban blues, it represented a synthesis of these styles into new rhythms born of subtle changes in syncopation and timing. More important, it was characterized by improvisation, with rhythmic subtleties that defied notation.

Jazz was not written down, and to the society at large this was pure heresy. It was equally distasteful to most veteran Black musicians. Ragtime, which enjoyed its greatest popularity between 1890 and World War I, and which contributed to the development of jazz, had represented a departure from traditional forms. But while it pitted complex African syncopation against a strong basic beat, ragtime was not improvised but carefully worked out, and usually written down.

By the end of World War I a definite jazz style had developed in New Orleans; there were also identifiable Chicago and Kansas City styles. But New York musicians had remained so conservative as to have no real style of their own. Between 1918 and 1921, stimulated by the influx of out-of-town musicians, young trombonists Charlie lrvis and Joe Nanton and trumpeters June Clark and Bubber Miley, among others, had begun to improvise and thus to take the first tentative steps toward a new style. They were criticized by the veteran musicians who resisted the change. In June 1921, J. Tim Brymn sermonized in a speech before five hundred members of the Clef Club:

“The different bands should follow their orchestrations more closely and not try so much of their ‘ad lib’ stuff. There is a growing tendency to make different breaks, discords and other things which make a lot of noise and jumble up the melody until it is impossible to recognize it. White musicians have excelled colored players because they are willing to supply novelty music and let it be done by the publisher’s arranger, who knows how to do it. If you find it necessary to improve on an orchestration have it done on paper so that the improved way of playing will be uniform and always the same.” (2)

While they may have been constrained to follow on-paper orchestrations when playing with the veterans and before for male audiences, the young musicians found encouragement for their tuneful ad-libbing on the streets of Harlem. Jazz was everywhere—on the corners, in the alleys, in sparerib joints. Vagabond musicians abounded, sought each other out, helped each other, learned from one another. It was a time of tremendous inventiveness, of spur-of-the-moment creativity. Faint but exciting sounds wafted across 110th Street. The ears of the uninitiated perked up and curious eyes looked northward.

White interest, and more important, white money, would help bring Harlem downtown and white downtowners uptown, would spur greater creativity and would give birth to the Harlem Renaissance, as future generations would know it. While many would prefer to believe that this renaissance would have occurred in spite of whites, evidence suggests— that without them it would not have assumed the major proportions it eventually reached.

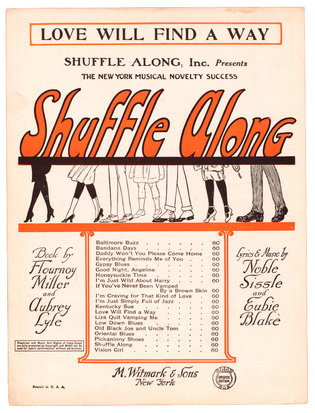

The event most frequently cited as the beginning of the commercial Harlem Renaissance is the revue Shuffle Along, which opened at the 63rd Street Music Hall on May 22, 1921. It was not the first Black show to penetrate to the heart of Broadway; certainly Black-influenced minstrel shows had played the Great White Way for years, and Black theater had been an important aspect of the American entertainment industry for years before that. Until 1891 the shows presented by Black entertainers had been of the strict minstrel variety, but in that year an ambitious Negro undertaking, The Creole Show, which glorified Black women, opened in Chicago. It contained many elements of the traditional minstrel shows, but it also represented the beginning of an evolution in Black shows that would lead directly to the musical comedies of Cole and Johnson and Williams and Walker. While it never actually made Broadway, it came very close by playing the old Standard Theatre in Greeley Square, the edge of the “Broadway zone.” The Creole Show was widely imitated in the next few years, but the minstrel format (a potpourri of acts with a male interlocutor prominent) was retained. A Trip to Coontown, which opened in 1898, was the first Black show to break completely with this tradition, the first to be written with continuity and to have a cast of characters working out a story from beginning to end.

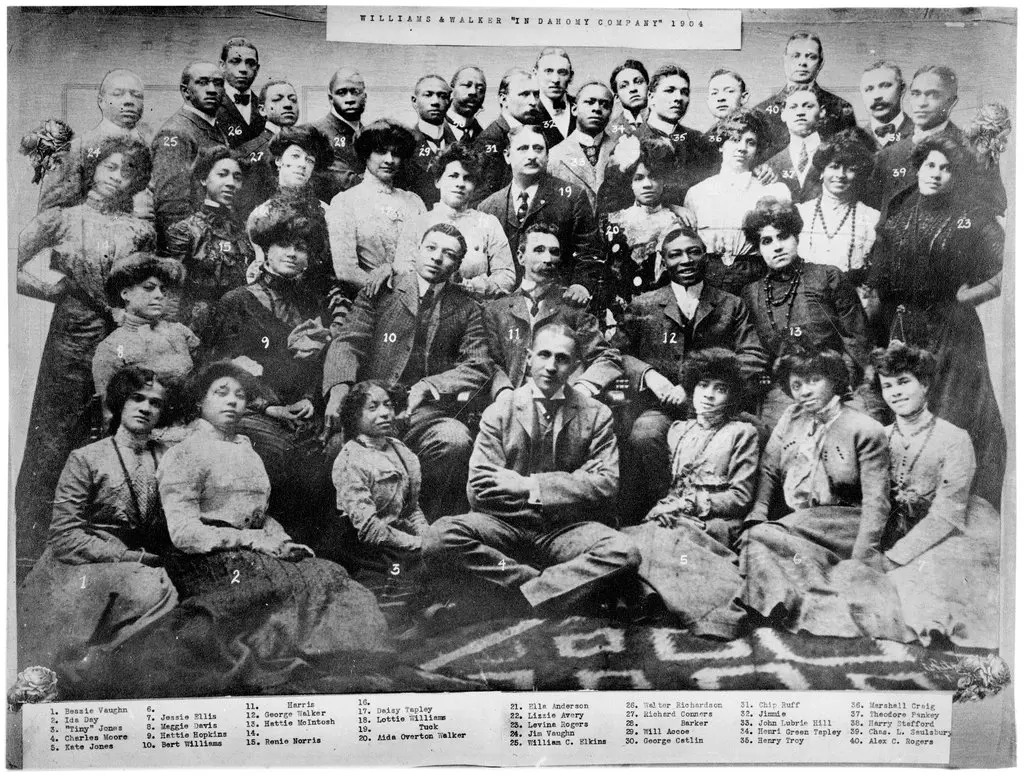

In ensuing years, composers began to write musical scores for such productions, and in 1902 the first completely Black show, In Dahomey, opened in the very center of the theater district, the New York Theatre in Times Square. Produced by the well-known comedy team of Williams and Walker, with a score by Will Marion Cook and lyrics by Paul Laurence Dunbar, the show later went to London and played a royal command performance at Buckingham Palace on June 23, 1903. It was followed, in 1906, by In Abyssinia, also starring Williams and Walker, and by Bandana Land in 1907. Both were highly successful shows, and it seemed that Broadway was now open country for Williams and Walker, that Black shows were there to stay.

But during the run of Bandana Land, George Walker fell ill, never to return to the stage again. Bert Williams appeared alone in A Lode of Kole in 1909, but the magic of the Williams/Walker duo was gone, and it was the last Black show in which he ever appeared. The following year he joined the Ziegfeld Follies. That same year the almost simultaneous deaths of three outstanding creators and performers—Ernest Hogan, Bob Cole and George Walker—signaled the end of this great era of Black theater. Except for Bert Williams, whose famous solo acts enlivened the Ziegfeld Follies for some years afterward, Black talent was abandoned by Broadway.

Black theater remained alive in New York, but in Harlem, not downtown. It was welcomed and supported by the Harlem community and enjoyed a tremendous period of creativity between 1910 and 1917, marked especially by the productions at the Lincoln and Lafayette theaters.

While Shuffle Along is generally considered the catalyst for downtown interest in Harlem, the first show actually to bring Broadway up to Harlem opened at the Lafayette Theatre in 1913. Darktown Follies was written and staged by Leubrie Hui, a former member of the Williams and Walker company. It was the subject of headlines and cartoons in the New York papers, and going to Harlem to see it became fashionable. Florenz Ziegfeld saw the show and bought the rights to produce the finale to the first act and several numbers in his own Follies. Had societal conditions been different, the Harlem vogue might well have started then. But World War I broke out, and national as well as New York attention turned to other matters. During the war years some old talent and some new dreamed of returning the Black show to Broadway.

That return began one summer evening in Philadelphia in 1920. The NAACP was giving a benefit, and among the acts scheduled to perform were the musical vaudeville duo of Noble Sissie and Eubie Blake and the comedy vaudeville team of Flournoy E. Miller and Aubrey Lyles. After the show both sets of performers met and decided to join forces to try to put the Negro back on Broadway. Less than a year later they did so, with a splash.

Shuffle Along was a swift, bright, rollicking show, crammed with talent. Hall Johnson, later a famous choir director, and composer William Grant Still were in the orchestra. Sissie and Blake, in addition to having written the music, played and acted in the show. Miller and Lyles outdid themselves in their comedy routines. Florence Mills’s career skyrocketed after her performance in the second act. Josephine Baker was in the chorus.

Shuffle Along was cast in the best Williams and Walker tradition, but its music was completely nontraditional. In fact, the success of Shuffle Along was due chiefly to its music and its choreography, for it legitimized ragtime music and jazz dancing.

Many of its tunes, among them “I’m Just Wild about Harry,” “Love Will Find a Way” and “In Honeysuckle Time,” became world-famous. In the earlier shows, ragtime had been hidden under the heavy overlay of operetta. By the time the show opened in New York, Blake had already won fame as a composer, and ragtime was present in pure form in Shuffle Along, providing white society the first real opportunity to hear, see and enjoy this first distinctly American music. Certainly there was some awareness of the blues, for example, but it, like the cabarets, was considered lower-class and associated too closely with Blacks. As one writer put it:

One is elevated by the drama, music and scenery of the opera. He brings away something worth while. In the cabaret, however (which is usually plunged deep beneath the ground, free from ventilation, where one’s clothes become thoroughly saturated with tobacco smoke and where no complaints of the ordinary passerby can be made against this generally recognized impossible music), he gets jaded, exhausted by the monotony and noise, finally returning to his home physically, mentally and financially depleted… it takes a much higher degree of education and training to produce operas than it does to write scrolls of the “blues.” Also, a race that hums operas will stay ahead of a race that simply hums the “blues.” (3)

Jazz struck a responsive chord in white society, and soon became the rage. Thousands flocked to the 63rd Street Music Hall to listen to the ragtime music and to watch and try to learn the jazz dancing. Responding to this new interest, “colored dance” studios opened up, many on Broadway, to teach Black dance styles like the “snakehips” to eager whites. Among the best-known and popular teachers was Billy Pearce. In his autobiography, critic Leonard Sillman recalled; “One day when I came to Billy’s for a lesson I looked into one of the studios and got an interesting view of a matronly female standing beside a victrola . . . She was getting ready to go into ‘Scarlet Sister Mary.’ To get the Negro rhythm, the Negro feel, Ethel Barrymore was studying Snake Hips at Billy Pearce’s.” (4)

Before long, this interest in the music and dancing of Shuffle Along shifted to an interest in Harlem. After all, downtown whites surmised, if such exciting things were happening in a Black show on Broadway, it followed that even more exciting things were happening up in Harlem. What, indeed, was going on up there?

Carl Van Vechten was one who told them. A music critic who had also turned to fiction in 1920, Van Vechten had been impressed with Black music for years, far in advance of most other whites. He now began to write magazine articles about the creative movement in Harlem, at the same time visiting Harlem and getting to know the writers and singers and musicians. They welcomed his sincere interest. His new acquaintances became the subjects of more magazine articles. White New Yorkers read these articles avidly, but they were not long content merely to read about what was going on. Soon they wanted to see for themselves.

A decade before, the white public would not have risen to the opportunity of enjoying and appreciating jazz. But in the postwar period, a fast and feverish era in the industrial development of the country was at hand. The war had radically changed national attitudes and the national rhythm. While for many it had signified a coming of age, in the view of others the significance was much less positive. The occurrence of a world war had resulted also in a loss of innocence. Some would call it a loss of ignorance, and applaud. But it was an unsettling experience to recognize the economic and political machinations that had led to U.S. involvement in the European war. The nation had lost its open faith in itself and in mankind. The war had caused many Americans to view the world differently, less optimistically, to take pride in a worldly cynicism but at the same time to mourn the passing of more naive days.

For most Americans the vague sense of unrest never reached conscious expression. Had the end of the war brought a sudden economic depression, the national mood might have been different. But wartime prosperity continued into the postwar era, and surface contentment reigned. Outright cynicism was expressed primarily by urban intellectuals and the urban wealthy. The intellectuals looked with distaste at the war-stimulated mass industrialization, bemoaned, as Carl Van Vechten put it, the “Machine Age,” that “profound national impulse [that] drives the hundred millions steadily toward uniformity.” They attacked the middle class and its values as puritanical and life-denying. Pseudointellectuals responded eagerly to the call, and cynicism became fashionable.

Urban “society” took up the fad. Wealthy sons and daughters revolted against the boredom of proper lives. The daughters led the way. A new age of freedom for girls was beginning. Women’s rights, women’s suffrage—the war had nurtured such ideas. Their men gone to war, the women of America had been forced in greater numbers than ever before to be independent and self-reliant. To be sure, it was the women of the lower economic classes who had worked in the war products factories and headed families, but it was on the backs of such women that the young socialites rode to adventure.

Harlem, and the Negro, seemed to embody the primitive and thrilling qualities sought by both intellectuals and socialites. To the intelligentsia, innocence was still alive in America in the Negro. In the Negro was all the sensuousness and life rhythm that white America had lost. To the socialites, Harlem represented a blend of danger and excitement. The exotic jungle rhythms gave intimations of sensuality beyond the wildest fantasies of the sons and daughters of proper New York society. Not that these fantasies were particularly inspired.

Sex in the twenties was quite tame. As Anita Loos put it: “How could any epoch boast of passion with its hit song bearing the title, ‘When You Wore a Tulip, a Bright Yellow Tulip, and I Wore a Big Red Rose’?” Four letter words were barred from popular books; pornography was accessible only to those with connections. Certainly “race records” with “blue” songs were available, but even these were much more implicit than explicit in their sexuality. A passionate tango rendition or a snapped garter in a dark corner were highly titillating experiences. Harlem was an adventure; Harlem was the unknown; and Harlem became a fad.

The Negro was in vogue, and in Harlem the speakeasy took on a new dimension. White downtowners invaded Harlem to observe the Blacks at play, “flooding the little cabarets and bars where formerly only colored people laughed and sang, and where now the strangers were given the best ringside tables to sit and stare at the Negro customers—like amusing animals in a zoo.” (5)

“White people,” the Black newspaper New York Age, commented, “are taking a morbid interest in the nightlife of [Harlem].” Some of the owners of the Harlem clubs, delighted at the flood of white patronage, encouraged their employees to give the white folks a good show. Waiters danced the jig or the Charleston as they waited tables. At the Savoy Ballroom, the dancers were inspired to unheard-of acrobatic feats for the entertainment of the white observers. More often, however, the Black patrons of the clubs merely acted as they always had, which was neither African nor exotic, and in time, tired of being stared at, they ceased to patronize the clubs.

Most Harlemites were suspicious of white people’s interest in them. They were accustomed to being shunned by whites, not sought by them. The memory of white reaction to Jack Johnson’s victory was vivid. White people just didn’t do such an aboutface; they had simply found a new way to exploit Blacks.

A kinship exists between this stereotype [of the New Negro] and that of the contented slave; one is merely a “jazzed-up” version of the other, with cabarets supplanting cabins, and Harlemized “blues,” instead of the spirituals and slave reels. (6)

In the minds of New York’s white leisure class, the change in the Negro’s image took place in a remarkably short time. Rudolph Fisher, known at the time as one of the wittiest Blacks in Harlem, was a writer as well as a physician. He had been away at medical school during the rise and establishment of the Harlem vogue. Returning to New York, he immediately went to his favorite basement spot, where he had once enjoyed the company of other young Blacks, and ignored the occasional party of white slummers in the corner. “I remembered one place especially where my own crowd used to hold forth; and, hoping to find some old-timers there still, I sought it out one midnight. ‘What a lot of “fays”!’ I thought as I noticed the number of white guests. Presently I grew puzzled and began to stare, then I gasped—and gasped. I found myself wondering if this was the right place—if, indeed, this was Harlem at all. I suddenly became aware that, except for the waiters and members of the orchestra, I was the only Negro in the place.” (7)

Fisher was in for another surprise. In the heart of Harlem, there were now white establishments!

A combination of elements gave rise to the Harlem Renaissance and to white interest in the so-called New Negro. So, too, a combination of many of the same elements created the climate out of which these “white clubs” arose, but here there was an additional, and major factor—Prohibition. It would, in a very fundamental way, divide the Harlem Renaissance into two parts—that of the Black writers and intellectuals and that of the Black musicians and performers. The former made their mark, or didn’t, regardless of the Volstead Act of 1919. The latter owed much to Prohibition, for had it not been for this attempt at legally enforced abstention, organized crime would not have moved into Harlem—at least not as early or with such vigor.

Most of the Irish cabaret owners moved out, and mostly Italians came in, although Dutch, German, Jewish and French mobsters were well represented, and some of the Irish simply made alterations in their already established businesses.

The mob bosses took people’s desire for bootleg liquor, coupled it with the interest of high-living white downtowners in Harlem, and parlayed the combination into the most profitable underworld business ever, until dope came along. And it was not long before the gangsters discovered they were an added attraction themselves. The “jet set” of the twenties felt a kinship with the bootleggers in flouting the law. White gangsters acquired a romantic image tinged with danger, and many played the role conscientiously, with their snap-brim Capone hats pulled low over their eyes, shoulders hunched, coat collars turned up and hands buried deep in their overcoat pockets. Bugsie Siegel became the most fascinating man around New York, and the American Princess Dorothy di Frasso the envy of many Park Avenue debutantes for attracting him.

Within a few years after the Prohibition law was enacted, a number of prosperous clubs catering to white sightseers had opened in Harlem. Many of them were located on 133rd Street between Lenox and Seventh avenues in a neighborhood known as “Beale Street,” a name made famous by W. C. Handy. But wherever their location, their basic formulae were the same: (1) cater primarily to whites and give them everything they want—an opportunity to observe exotic entertainment, a chance to participate without crossing, to any appreciable degree, the color line, a chance to be in but not of Harlem, (2) and more important, sell a lot of bootleg liquor.

Some actively barred Blacks; others were willing to serve whoever could pay. But in nearly all clubs there was a substantial white presence, a presence not open to question or criticism. As the writer who described the Palace Casino incident put it:

. . . who would think of ordering white people out of a colored dance in Harlem today, unless it was a private or a club function? The white people come in larger numbers today and have acquired a financial interest in Harlem’s social life, especially the night life. The same manager would perhaps throw a Negro out today if he protested, on the grounds of breaking up his business. The same ladies who squawked so loudly that night about the presence of white men would be boasting today that New York is so cosmopolitan, or, perhaps, Bohemian. (8)

These clubs existed side by side with Harlem characters like the Messiah, who walked the streets barefoot, summer and winter, urging the people he passed to “Repent!,” and with the New York City police, who acted more as a security force for the clubs than as protectors of the people in the neighborhood. The clubs existed in spite of the Committee of Fourteen, a self-appointed group of Prohibition-minded citizens who branded the Harlem nightclub district a menace, and in spite of the moralizers against sex and racial mixing who seemed, like the Prohibitionists, to spend an inordinate amount of time “studying” the area in order to identify its sins.

Rollin Kirby caricatured the figure of Prohibition as suspiciously red-nosed, suspiciously tipsy and carrying a bottle in his hip pocket. The writer Hendrik de Leeuw quite effectively caricatured himself and other anti-sin crusaders when he wrote about Harlem in his Sinful Cities of the Western World:

I beheld brown-skin vamps and other gay colored silhouettes, romp from lantern post to post. I saw white women trot along, prancing and strutting with negroes . . . swarms of people with banjoes and ukes strumming, gurgling sensual music, while from side streets one could almost hear the heavy snoring of dusky inhabitants, sleeping the sleep of the jungle man . . .

I came to the Night Club . . . This place is said to be the most exclusive in the Black and Tan. Negroes—superbly dressed American women, waiters carrying heavily laden trays with booze for Americans that know not how to drink—whites on top of blacks, red and yellow lights flashing over moving bodies—a colored wench , gorgeously attired, with a face like a mongrel and a beetle brow—all gliding and prancing and swinging and prowling, impeded me as I fought my way to the door—where many feet deep stood another mob, aching to get in. (9)

Each club had its own particular flavor. Many changed hands several times in the initial scramble to exploit the New Negro/bootleg liquor business. Some became famous only to New Yorkers, others to most Americans. Some survived for many years, others for only a few. There was Broadway Jones’s Supper Club, which was opened by the popular tenor vocalist at 65 West 1 29th Street about 1920. In 1919, following the opening of a new Sissie-Blake revue entitled Bamville, the club’s name was changed to the Bamville Club. The club gave a “welcome home” banquet for Florence Mills upon her return from Europe in 1927. She died one week later.

There was Barron’s (Wilkins) Exclusive Club. Barron D. Wilkins had already run an established enterprise, the Little Savoy, in the midtown Tenderloin district (West 35th Street) before moving up to Harlem to open a club bearing his name around 1915. Obviously possessing an ear for musical talent, Wilkins employed, in those early Harlem years, such performers as Willie “The Lion” Smith, Ada “Brick Top” Smith, and Elmer Snowden’s Washingtonians, of which Duke Ellington was a member and would later be leader.

There was the Clam House, at 131 West 133rd Street, a favorite early-morning eating spot, where Gladys Bentley dressed in male attire and entertained the guests with naughty songs.

There was Connie’s Inn, on the corner of 131st Street and Seventh Avenue. Originally it was opened as the Shuffle Inn in November 1921 by Jack Goldberg, who attempted to capitalize on the success of Shuffle Along on Broadway. At the time, George and Connie Immerman were in the delicatessen business, employing ” Fats” Waller as a delivery boy. When the lmmermans decided to go into the Harlem nightclub business, they selected the Shuffle Inn for, among other reasons, its excellent location. In front of its Seventh Avenue façade was Harlem’s famous Tree of Hope.

Connie’s Inn became one of the three most popular nightspots in Harlem. Its peak period came in 1929 when Louis Armstrong came in from Chicago to star in the show Hot Chocolates. “Fats” Waller and Andy Razaf wrote the score for the show, which played simultaneously at the Hudson Theatre on West Forty-Sixth Street. “Ain’t Misbehavin'” and “Can’t We Get Together?” were two of the songs that came out of that show.

There was Ed Small’s Paradise, opened around 1925 by a former elevator operator and a descendant of the Black Civil War hero Captain Robert Smalls. With Connie’s Inn, it became another of the three most successful night clubs in Harlem during Prohibition. There was the Nest Club, and Pod’s and Jerry’s, the Silver Dollar Cafe, and the Breakfast Club, Connor’s and the Hollywood Cabaret . . .

. . . And there was the Cotton Club, the first in fame of Harlem’s “Big Three” night clubs of the era. Some would add, “First in notoriety,” for its “whites only” admittance policy, but others would add, “First and foremost in bringing Broadway to Harlem. . . and Harlem to Broadway.” Whatever the reasons, there are few Americans over age twenty who have not heard of the Cotton Club. This is why.