2 The Cotton Club

About 1918 a building was constructed for amusement purposes on the northeast corner of 142nd Street and Lenox Avenue. Built to compete with the very successful Renaissance Casino on West 133rd Street, the Douglas Casino was, like the Renaissance, a two-story building and intended as a dual operation. On the street floor was the Douglas Theatre, which featured films and occasional vaudeville acts such as magicians and strong men. One flight up was a huge room, originally intended to be a dance hall. Plans to book some of the big dances, banquets and concerts away from the Renaissance were unsuccessful, and the dance hall remained essentially unused until around 1920. The former heavyweight champion Jack Johnson, who also happened to be an amateur cellist and bull fiddler, and who was a connoisseur of Harlem night life, rented it and turned it into an intimate supper club, the Club Deluxe.

Even reborn as a supper club, however, the place failed to attract attention, until Owney Madden’s gang came around looking for a suitable spot for the entertainment of white downtowners and to serve as the principal East Coast outlet for “Madden’s No. 1” beer. The Club Deluxe seated 400-500 people, and it was just the place for which the syndicate was looking. Madden’s people made a deal with Johnson under which the group would operate the place but Johnson would be kept on in a semimanagerial position. The ex-fighter eagerly accepted.

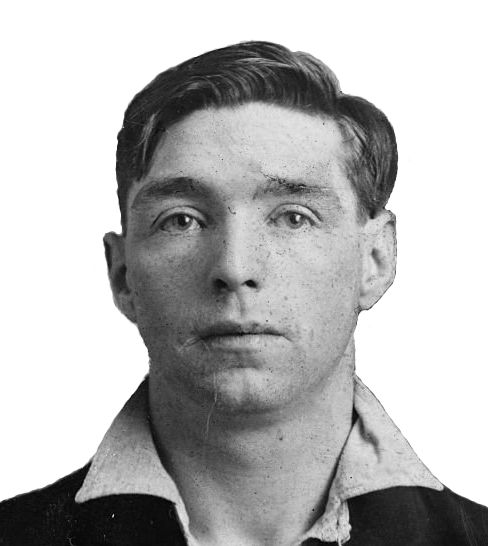

Owen “Owney” Madden was not personally involved in the transaction. He was in Sing Sing at the time, having been convicted in 1914 of manslaughter in the killing of one Patsy Doyle in an Eighth Avenue saloon.

Owney Madden had been one of the most notorious of the pre-Prohibition gang leaders. Born in England, he had come to the United States at the age of eleven and had acquired the nickname Owney the Killer when only seventeen years old. He was eighteen when he assumed command of one of the factions of the Gopher Gang, the largest gang in Hell’s Kitchen. A slim, dapper young man, he did not have much interest in the gambling and prostitution operations favored by some of his colleagues. His principal businesses were sneak thievery, stickups, loft burglaries, “protection” contracts with merchants and saloon keepers, and collections from corrupt politicians. He boasted that he had never worked a day in his life and never would.

Madden did not look like a hood; he had the gentlest smile in New York’s underworld. But he possessed great cunning and was capable of extreme cruelty. Brash and ambitious, he made no secret of his desire to be king of all the gangs, and he was willing to kill anyone who stood in his way. By the time he was convicted of the Doyle killing, the police had attributed four other murders to him personally and several more to his henchmen.

Owney Madden had many enemies, and there were several attempts on his life after he took over the Gopher faction. None came near to succeeding until the night of November 6, 1912, when Madden went to the Arbor Dance Hall and became interested in a pretty young woman. By the time he noticed the eleven thugs, they had surrounded him and started firing. Surgeons dug six bullets from his body, and it took him months to recuperate. The word went out to Madden’s men, and in less than a week after the shooting, three of the eleven men had been murdered.

With Madden in the hospital, other gangsters sought to take over his territory. Patsy Doyle began spreading the rumor that Madden was permanently crippled. Apparently this rumor disturbed Madden more than others’ attempts to displace him, for as soon as he was released from the hospital he set out after Patsy Doyle.

The murder was Madden’s undoing. Two or three days after the Doyle killing, Madden was arrested. When he was convicted and sentenced to Sing Sing for ten to twenty years he was just twenty-three years old. His conviction and imprisonment had a profound effect on him. Though he would continue to exercise considerable power in the underworld he did so less conspicuously, avoiding as much as possible further trouble with the police and with his underworld enemies.

Despite his confinement, Madden maintained tight control over his syndicate and closely watched trends in the outside society that could be exploited for profit. When the Prohibition law was passed, Madden realized, along with other gang leaders, that to go into the Harlem cabaret field was good business. It was not necessary for him to be present for the actual arrangements; in fact, he preferred otherwise. He shunned publicity, and even after his parole, was seldom seen at the Cotton Club.

Like other syndicate-owned clubs, the new club was run by a “front man.” Walter Brooks, who had brought Shuffle Along to the legitimate theater, served in this capacity, assisted at times by Jack Johnson. Madden was listed as a minor officer of the corporation, and the president was a little-known pickpocket named Sam Sellis. But the syndicate realized that there were economic advantages to a certain amount of visibility. George “Big Frenchy” DeMange, one of Madden’s closest aides, was made secretary of the corporation formed to operate the club. One of the duties of this rotund, card-playing French man was to spend time at the club, giving the patrons the added kick of rubbing elbows with mobsters.

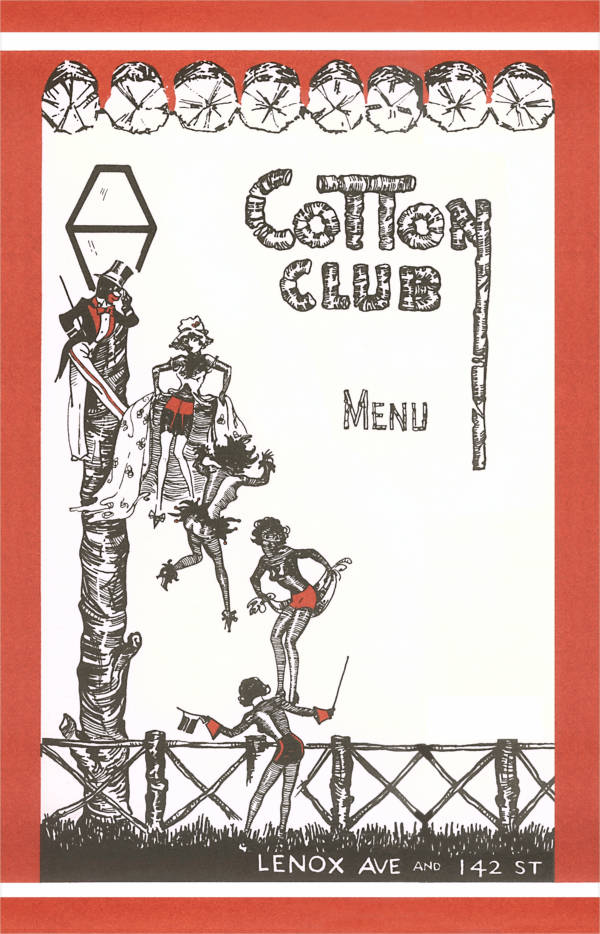

The Madden people moved in. The first order of business was to change the club’s name. The exact derivation of the name Cotton Club is not known, but it is likely that the club’s intended “whites only” policy, together with intimations of the South, were behind the choice.

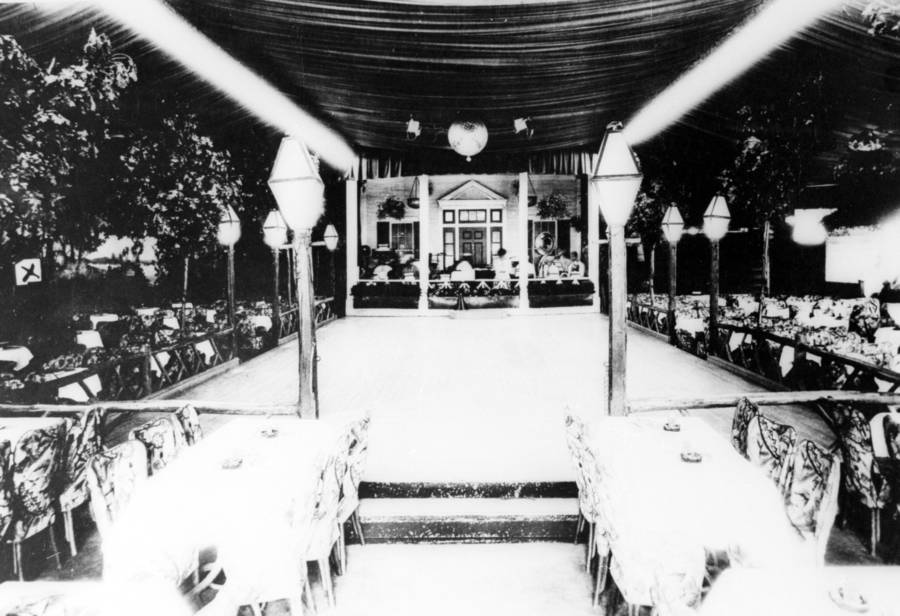

The next concern was to stretch the seating capacity of the room to the limit. In the classic cabaret manner, it was arranged in a horseshoe shape, with the audience seated on two levels. Some of the tables surrounded the dance floor in front of the tiny proscenium stage, some were on a raised area in the back. The walls were lined with booths, and as many tiny tables as could fit were crammed in on both levels. Seating capacity was thus raised to about 700.

The club was refurbished to cater to the white downtowners’ taste for the primitive. It was a “jungle decor,” with numerous artificial palm trees. Draperies, tablecloths, fixtures were elegant. The idea, like Johnson’s, was to create a plush late-night supper club, and to charge prices befitting such luxury.

The menu was designed to appeal to a variety of tastes. Besides the basic steak and lobster fare, it would offer Chinese and Mexican dishes, as well as a liberal sampling of “Harlem” cuisine, such as fried chicken and barbecued spareribs.

To ensure the loyalty of their workers, the Madden people turned to Chicago for their nonentertainment staff. Busboys, waiters, cooks, the various workers for the syndicate, the hangers-on-all were imported from Chicago. Most of the entertainers came from there, too. Not until 1927 did the Cotton Club band become a non-Chicago group.

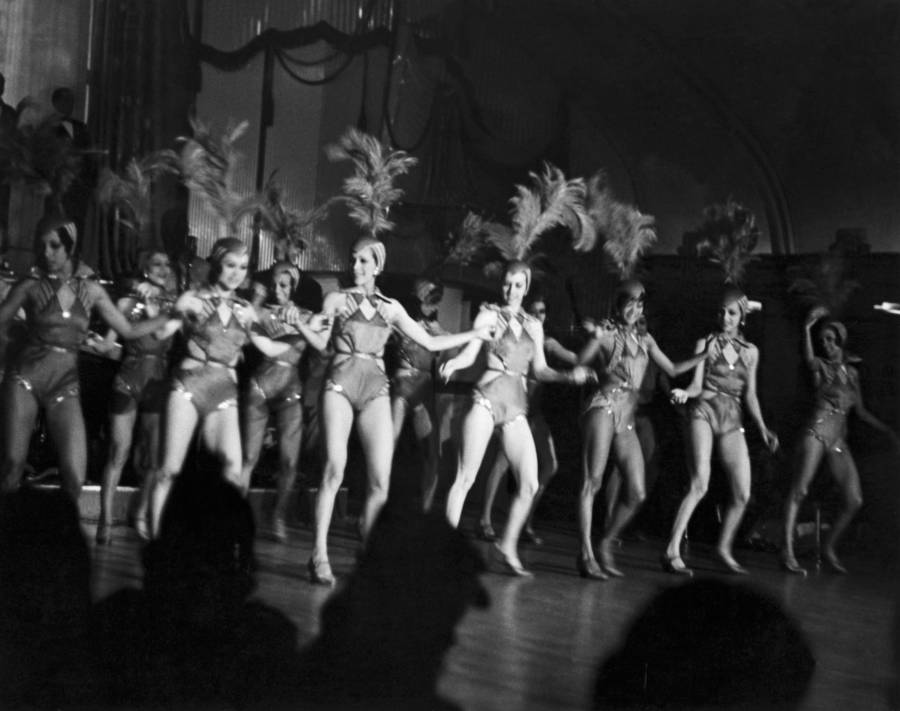

There were other restrictions that applied to the entertainers. The chorus girls had to be uniformly “high-yaller,” at least 5’6″, dancers, and able to carry a tune. And they could not be over twenty-one.

Rounding out the entertainment would be the male dancers, individual acts, brother acts. Skin color was not important in the choice of male dancers. Their dancing ability—high-stepping, gyrating, snakedancing—was.

It was decided that the Cotton Club floor show should be a multileveled, fastpaced revue, a new one twice a year, staged in a lavish Ziegfeld manner. Lew Leslie, who later gained fame through his Blackbird revues on Broadway, was hired as producer. Boston songwriter Jimmy McHugh, who had acquired a certain amount of fame during World War I with his “Inky Dinky Parlez-Vous,” would do the songs, and Andy Preer’s orchestra, the Missaurians, was brought from Chicago and renamed Andy Preer’s Cotton Club Syncopators. Other creators and performers were hired according to a single formula: all those who were involved in production, staging, choreography, set and costume design were talented whites, and all those who performed were talented Blacks.

In January 1923, Owney Madden was paroled from Sing Sing, released on good behavior after serving approximately eight years of his ten-to-twenty-year sentence. He left the preparations for the Cotton Club’s opening to his lieutenants and associates and concentrated on his beer business, although it is likely that more than beer passed through his downtown factory. A few months after his release from prison, he and five other men were arrested near White Plains, a suburb of New York City, for riding in a truck containing $25,000 worth of stolen liquor. At his arraignment he managed to get the charges dismissed when he told the court he had simply hitched a ride on the truck and did not know what kind of cargo it was carrying.

In the fall of the same year the Cotton Club staged its grand opening. The show was essentially an uptown version of the lavish Negro stage revues that were selling out theaters down on Broadway. The Cotton Club customers had seen these revues and had come uptown to get a closer look. The Cotton Club orchestra thus had to be a show orchestra, playing to an audience that often had just left one of the top revues and wanted to hear music in the same slick commercial style. The Cotton Club girls were beautiful, glamorous, dressed in revealing costumes. The songs were memorable. In those early years, McHugh would introduce such popular numbers as “I Can’t Believe that You’re in Love with Me,” “When My Sugar Walks Down the Street” and “Freeze and Melt.”

The customers were impressed with the show. More than that, they were impressed with the ambience, the mood of the Cotton Club. Impeccable behavior was expected—demanded—of the guests, particularly while the show was going on. A loud-talking customer would be touched on the shoulder by a waiter. If he persisted in his talking, the captain would politely ask him to keep his voice down. If this attempt was unsuccessful, the headwaiter would remind the customer that he had been warned; and if even this reminder proved futile, the loud talker was thrown out. This policy continued throughout the Cotton Club’s Harlem days and was one reason why the club had less trouble than most other Harlem night clubs.

The staff—waiters, busboys—behaved with equal decorum. The waiters at some of the other clubs did the Charleston while balancing their trays; the waiters at the Cotton Club considered such public display in extremely bad taste. But their actions were of more than casual interest to the customers, for their motions were marvels of studied elegance. Everything, from menus to drinks to meals, was served with a flourish. When conspicuous spenders wished to heighten their visibility, the Cotton Club waiters obligingly caused the champagne bottle corks to pop louder and fly higher than usual.

As was the custom in most “speaks,” the patrons who did not wish to drink beer brought their own liquor, although those who came unprepared could make a separate deal with the waiter or doorman. A bottle of fairly good champagne could be had for $30 and a fifth of Scotch might cost $18. Beer was less expensive but still costly enough, as were the club’s other prices, to keep out undesirable customers.

Among those considered undesirables were Blacks, even in, or perhaps particularly in, mixed parties. Carl Van Vechten reported: “There were brutes at the door to enforce the Cotton Club’s policy which was opposed to mixed parties.” Only the lightest-complexioned Negroes gained entrance, and even they were carefully screened. The club’s management was aware that most white downtowners wanted to observe Harlem Blacks, not mix with them; or, as Jimmy Durante put it, “it isn’t necessary to mix with colored people if you don’t feel like it. You have your own party and keep to yourself. But it’s worth seeing. How they step!” (1)

The Cotton Club eliminated the need for conflict or guilt—all the performers were Black, all the observers were white. Durante suggested another reason for the club’s “whites only” policy: “Racial lines are drawn there to prevent possible trouble. Nobody wants razors, blackjacks, or fists flying—and the chances of a war are less if there’s no mixing . . . ” (2)

Another factor responsible for the club’s popularity was that it was among the few clubs that offered entertainment so late at night that the show-business crowd could catch a show there after their own work was done. Their presence, in turn, attracted non-show-business patrons.

It was not long before the Cotton Club became known as the “Aristocrat of Harlem,” as Lady Mountbatten dubbed it.

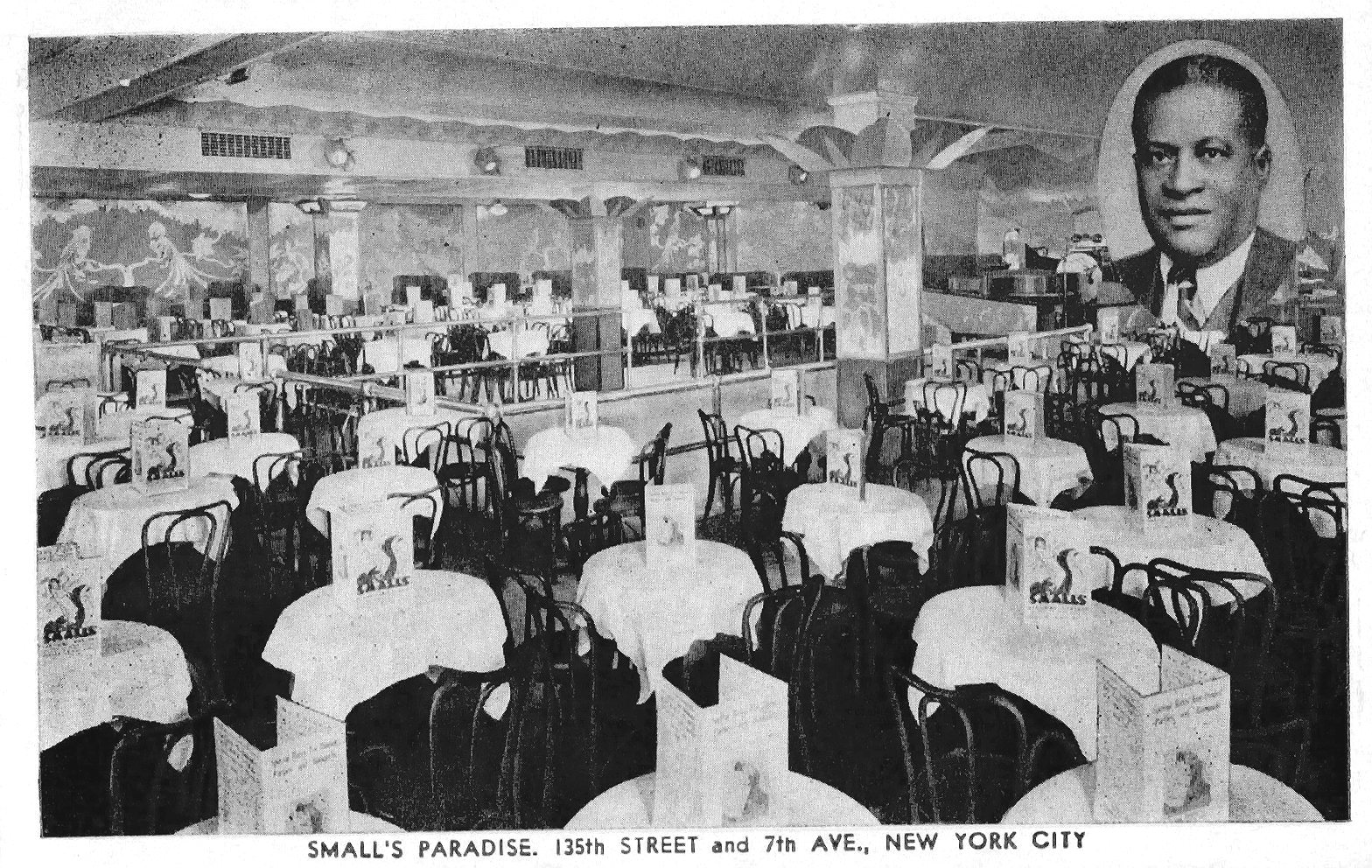

Other clubs opened, all based on the successful Cotton Club idea, some with variations on the theme. Small’s Paradise, at 229½ Seventh Avenue, staged a gala opening in the fall of 1925. The large cellar was packed with 1,500 people that evening. Small’s also catered to the tastes of the white downtowners. It stayed open later than the Cotton Club and most other clubs, and its specialty was early-morning breakfast for all-night revelers. The waiters at Small’s, copying those of some other clubs, did the Charleston while balancing full trays of bad whiskey. Unlike the Cotton Club, Small’s admitted Black patrons, although its prices successfully shielded the white downtowners from the “colored rabble.”

Small’s flourished. Many of the others that opened around the same time did not. Most did not last more than two or three weeks; they lacked “class.” One was much like the next. The ingredients: bootleg liquor and a good show for the white folks. But as one folded, two more took its place. Harlem was a honeycomb of speakeasies and drinking dives, and these, along with the seven major night clubs and eighteen dance halls for mixed patronage, led the Committee of Fourteen to brand the district a menace.

This was hardly news to the police. They were quite aware of the illicit activities in Harlem, and elsewhere in the city. Their problem was that the small joints were such fly-by-night operations, so “portable,” that by the time the cops got inside, the evidence had vanished. As for the big clubs, generally their “management” had an understanding with the police and detectives. The clubs ran comparatively clean and peaceful operations, paid regular bribes, and in return the cops let them go about their business. The same arrangement did not hold with the Feds, who were less vulnerable to appeals to personal greed than local law-enforcement officials. The Feds had just as much trouble as the local cops catching the small cabaret owners with incriminating bootleg liquor. But they had considerably greater success with the larger clubs. In June 1925 Federal Court Judge Francis A. Winslow placed a padlock on the Cotton Club’s door and on those of eight other clubs, pending resolution of charges that the clubs had violated Prohibition laws.

Both Madden, as secretary, and Sellis, as president, were named in the indictment, which charged forty-four violations of the Volstead Act. The criminal records of both men were offered by Assistant U.S. Attorney Bellinger as evidence against them. In pleading their case, Madden and Sellis assured Judge Winslow that they had tried to “make good” since their last prison sentences. In the end they and the club got off rather lightly, for neither man was sent back to prison; however, a substantial fine was levied against the club, and the loss of revenue resulting from the club’s three-month closing constituted a substantial penalty in itself.

When the Cotton Club reopened, several changes had been made, changes that proved to be fortunate for it. Walter Brooks had been replaced as front man by Harry Block, and Herman Stark, who was hired essentially as stage manager, finally found his true calling at the Cotton Club. A former machine gunner, Stark looked like a typical stage manager—gruff, stout, cigar chewing—but more important, he had the mind and the thinking of a stage manager. Under his direction the Cotton Club reached its apogee. It was Stark who persuaded the club’s management to hire Dan Healy to replace Lew Leslie as “conceiver and producer” of the Cotton Club shows, and it was under Healy’s direction that the shows took on their now famous form.

Healy was young, but already he was a show-business veteran, He was best known for his portrayal on the night of July 16, 1919, when Prohibition went into effect, of the now famous Rollin Kirby caricature that was to represent the figure of Prohibition. On the stage of the Majestic Theatre, Healy, reeling across the stage, a bottle sticking out of his hip pocket, symbolized to perfection “the gaunt, cruel-lipped chap with the funereal get-up, the high hat and the suspiciously boozy nose.” Little did he know at the time that some years later he would be hired by an establishment that thumbed its nose at the Prohibition law almost as effectively.

Healy had appeared in legitimate musicals, among others the Rogers and Hart show Betsy, and Kalmar and Ruby’s Good Boy. He could dance, sing and do ad-lib comedy, and he was among the most energetic performers around. Still, he was not hired by the Cotton Club for these talents alone, for he also had considerable production experience, some in association with the Madden syndicate. After staging shows for the Choteau Madrid, for “Legs” Diamond’s Frolics, and for shows in Atlantic City and Philadelphia clubs, he had produced shows for the Silver Slipper in New York, which was also owned by the Madden-DeMange group. In coming to the Cotton Club, he simply transferred to another branch of the corporation.

Healy was highly pleased with his Cotton Club assignment, for it allowed him unbridled exercise of his fast-stepping, up-tempo tastes in entertainment. “The chief ingredient was pace, pace, pace!” he later said, explaining his formula for the shows. “The show was generally built around types: the band, an eccentric dancer, a comedian—whoever we had who was also a star. The show ran an hour and a half, sometimes two hours; we’d break it up with a good voice… And we’d have a special singer who gave the customers the expected adult song in Harlem…” (3)

The acts themselves were only part of Healy’s formula. Production was also important, and under Healy’s direction the Cotton Club became probably the first night club to feature actual miniature stage sets and elaborate lighting as well as spectacular costumes.

Ever since the start of prohibition, the mobster element had been extending its control over Harlem night life, and early in 1926 one of the holdouts, or pre-Prohibition night-club operators still in business, was dealt with in gangland fashion. Realizing that in order to keep his exclusive club open it was necessary to make some concessions to the various syndicates that had invaded Harlem, Barron Wilkins had for five or six years purchased his bootleg liquor from the gangsters. As one story goes, around late 1925 or early 1926 he received a shipment that he considered inferior and refused to pay for it. In response to such insubordination, the boys dispatched Yellow Charleston, a well-known junkie of the era, to deal with him. Early one morning in 1926, Charleston stabbed Wilkins in front of the Exclusive Club.

According to another story, Wilkins had refused to lend Charleston a trifling sum of money, and Charleston’s act was individual and not mob-directed. Whatever the reason, Barron Wilkins was killed, and shortly thereafter the Exclusive Club closed, to be reopened under new names and new management again and again but never to regain its former popularity. Although there is no proof that Madden’s gang was directly involved in the elimination of Wilkins, and thus of his club, the loss of a major competitor did nothing to hurt the Cotton Club’s business.

Sporadic outbreaks of gang violence occurred throughout the twenties, but underworld tensions and conflicts in New York did not compare to those in Al Capone’s Chicago. When the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre rocked Chicago in 1929, New York gangdom was enjoying relative peace, although that peace was shattered the following year.