3 Duke Ellington Comes to the Cotton Club

Many who are familiar with Harlem—and music—history remember 1927 as the year singer Florence Mills died. It was a sudden, tragic occurrence. One week before, she had been feted at a “welcome home” banquet upon her triumphal return from Europe, and all Harlem mourned her passing in one of the most elaborate funerals in Harlem history. It was also the year when Andy Preer died, and when the Cotton Club found a new band that would make it famous.

Preer’s group, the Missourians, or the Cotton Club Syncopators, was an average band; its entree to the Cotton Club had been due chiefly to the fact that most of the members had played in and around Chicago or came from there. Without Preer they did not have sufficient drawing power, so the club’s owners decided to bring in a new group.

Harry Block, the club’s boss at the time, offered the spot to Joe (King) Oliver, whose Dixie Syncopators were just finishing up more than six years of gigs in Chicago. But the King turned down the offer—not enough money for a ten-piece band, he said. (This, when Cotton Club performers were the highest paid in Harlem.) The opening of the new show had already been postponed to December 4 because the club was without a band, so the turndown put Block in a quandary.

Jimmy McHugh, by then a veteran and respected member of the Cotton Club entertainment team, spoke up. He knew of a band, he said. It had been at the Kentucky Club in Times Square for a year and was now at a theater in Philadelphia. Duke Ellington and the Washingtonians played the kind of music McHugh wanted for the show.

At first McHugh’s suggestion went unheeded. Ellington’s band was out of Washington, D.C.; it had never been near Chicago. While the tradition of hiring Chicagoans had been allowed to elapse with respect to waiters, cooks, busboys, and so forth, it was still strong when it came to hiring bands. But McHugh persisted, and Jack Johnson lent his support. Finally Block agreed to audition the Ellington band.

. . . the job [as Ellington would recall] . . . called for a band of at least eleven pieces, and we had been using only six at the Kentucky Club. At the time, I was playing a vaudeville show for Clarence Robinson at Gibson’s Standard Theater on South Street in Philadelphia. The audition was set for noon, but by the time I had scraped up eleven men it was two or three o’clock. We played for them and got the job. The reason for that was that the boss, Harry Block, didn’t get there till late either, and didn’t hear the others! That’s a classic example of being at the right place at the right time with the right thing before the right people. (1)

Block liked what he heard and signed a contract with Ellington’s agent, Irving Mills. However, a new problem then presented itself. The band’s contract to play at Gibson’s Standard Theater in Philadelphia ran for a week beyond the date of the Cotton Club’s planned opening, and Clarence Robinson firmly refused to release the band any earlier. In desperation, McHugh pleaded with the Madden people to do something. They did.

They called Boo Boo Hoff, a friend and a powerful underworld figure in Philadelphia. He in turn called Yankee Schwartz, who often acted as his emissary in such situations. “Be big,” Schwartz advised Clarence Robinson, “or you’ll be dead.” With much haste the theater’s management amended Ellington’s contract.

Ellington and his band finished their job in Philadelphia on the day of the Cotton Club’s new opening. Then they headed north, arriving just minutes before show time. Tired and nervous, the band did not play well that opening night. The customers responded only politely, and Block complained to McHugh that Ellington’s sound was too jangling and dissonant. McHugh chewed his nails and wondered when he would be given his walking papers.

Both Ellington and McHugh survived that opening night, and they could thank the Black musicians of Harlem and the proprietor of “Mexico’s” gin mill on 133rd Street for helping Ellington’s band come through at the Cotton Club after a shaky beginning.

The musicians had begun to follow Duke Ellington and the Washingtonians when they first appeared at the Kentucky Club, and had followed it closely since then, buying its records, talking it up. When word came that Ellington was opening at the Cotton Club, the musicians increased their supportive efforts. So did “Mexico,” who bet $100 and a hat that the Ellington band would make the grade. “Mexico’s” real name was Gomez, and he came from South Carolina. His nickname derived from his service as a machine gunner with General Funston against Pancho Villa. He ran “the hottest gin mill in town” according to Harlem’s musicians, and they spent hours at his place, drinking his “ninety-nine per cent”: “One more degree either way would bust your top,” Ellington used to say. At every opportunity Mexico praised the Ellington band, and the fact that he had bet so much on the Washingtonians inspired considerable respect. Mexico knew what he was talking about; Ellington’s band would run a first gig of five years at the Cotton Club.

The strict color line at the club prevented the Black musicians from showing their support in person, but they talked up the opening in all the uptown bars. Eventually the news crossed 110th Street and reached the ears of downtown white musicians, who traveled to Harlem to see what the talk was all about. The significance of their presence was not lost on the Cotton Club people. Before long, Duke Ellington and the Washingtonians were in tight. The Chicago-oriented Cotton Club people became their greatest fans.

The Cotton Club show that had opened fifteen acts with a number of encores. Ellington’s band usually led off with a show piece and played two or three numbers during the revue, almost always including their “Harlem River Quiver,” which they had recorded on the Victor label. The bulk of the show was written by Jimmy McHugh, although for part of it he had a partner, Dorothy Fields. The McHugh-Fields team was destined to make musical history.

The twenty-three-year-old Miss Fields came by her talent naturally, for she was the daughter of Lew Fields of the famous Weber and Fields vaudeville and musical comedy team. She did not, however, come by her profession easily, for Lew Fields was adamant about not letting any of his children become involved in the theater. Stubbornly Dorothy went her own way, working at whatever job she could find while writing songs and waiting for a break. (She got the idea for Annie Get Your Gun while working as captain of the kitchen at the Stage Door Canteen. One of the dishwashers she supervised was Alfred Lunt.) Dorothy did not even tell her father when she took the opportunity to team up with composer McHugh; she knew he would violently oppose her association with a mobster-operated Harlem night club. In fact, she had misgivings about the situation herself, but as things turned out, she could not have chosen a physically safer place to begin her lyric-writing career.

“They were such gentlemen,” she later said, referring to Stark, DeMange and company. “That was my first job as a lyric-writer, doing the Cotton Club shows with Jimmy McHugh. The owners were very solicitous of me; they grew furious when anyone used improper language in my presence . . . Stark took me up one day to see his prize pigeons. He lived over the club and kept the pigeons on the roof. He was very attached to them. He had become acquainted with pigeons in prison, when they had perched on the window sill of his cell. He had considered them his only friends there.” (2)

With such accounts, Dorothy was able to convince her father that she was in no danger at the Cotton Club, and at the opening a proud Lew Fields was in the audience. He had brought Walter Winchell along to observe his daughter’s work, which in that first show consisted primarily of the lyrics to one song that was performed probably by Edith Wilson.

When it came time for the song, Dorothy looked over at her father and beamed with pride. She was certain the song would dissolve his reservations about her making a career in show business. But as the singer began the number, Dorothy flushed with anger and embarrassment. More than anything else, she wished her father were not there to hear it.

The singer had changed the lyrics. They were so dirty I blushed. I told Pop I was not the author. He went to the owner, who was a big gangster of the period, and told him that if he didn’t announce that his daughter did not write those lyrics he would knock his block off. The gangster obliged. It was a poor start in show business. (3)

Nevertheless, Dorothy Fields remained in show business and at the Cotton Club, where she and McHugh produced some of the most famous songs in popular-music history.

The big numbers in that Cotton Club show were Dancemania and Jazzmania, and in them McHugh captured the essence of the attitude toward jazz of the day. Ellington and the band, however, supplied the rhythms and the instrumental voices that transmitted the “madness” to their audiences. Harry Carney on baritone sax, Rudy Jackson on tenor sax, Louis Metcalf on trumpet, and Wellman Braud, the bassman, all did their part. But it was the originals—Ellington, Toby Hardwick on alto saxophone, James (Bubber) Miley and Freddie Gay on trumpet, Joe Nanton on trombone and Sonny Greer on drums—who were most responsible for the band’s exciting sound.

Greer and his drums provided the focus of the band’s music. He had an incredible battery of percussion equipment, everything from tom-toms to snares to kettle drums, and once he realized the band was at the club to stay awhile, he brought in the really good stuff. He later recalled:

When we got into the Cotton Club, presentation became very important. I was a designer for the Leedy Manufacturing Company of Elkhart, Indiana, and the president of the company had a fabulous set of drums made for me, with timpani, chimes, vibraphone, everything. Musicians used to come to the Cotton Club just to see it. The value of it was three thousand dollars, a lot of money at that time, but it became an obsession with the racketeers, and they would pressure bands to have drums like mine, and would often advance money for them. (4)

With such equipment, Greer could make every possible drum sound, and at the Cotton Club he awed the customers, conjuring up tribal warriors and man-eating tigers and war dancers. But his rhythms were only the focus of the band’s sound. Every section contributed its own finely tuned, finely rehearsed part of the jungle sound, and the sections blended together so well that it was hard to distinguish the individual elements. Paul Whiteman and his arranger, Fred Grote, visited the Cotton Club nightly for more than a week but finally admitted that they could not steal even two bars of the amazing music.

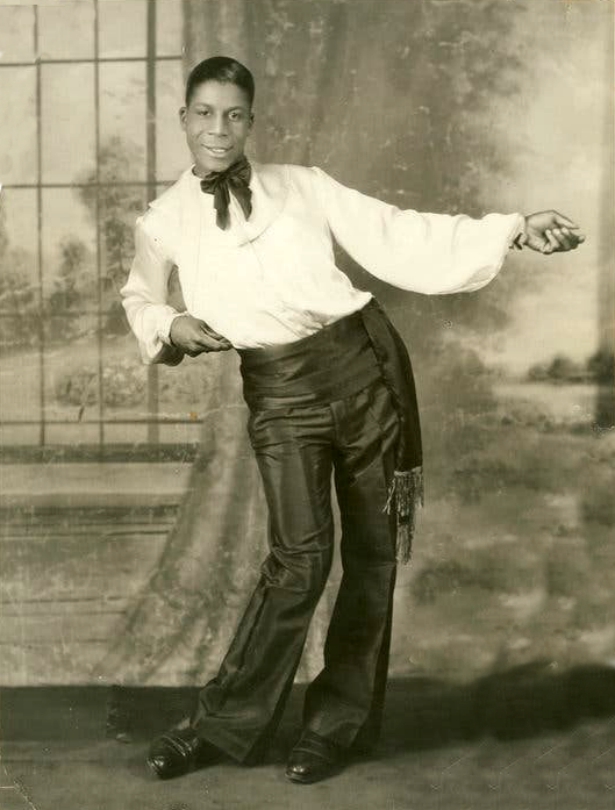

The featured Cotton Club singers and dancers completed the exotic image. Earl “Snakehips” Tucker could twist his haunches and thigh joints into unbelievable contortions. He was called a human boa constrictor and became an immediate sensation. Edith Wilson wore an abbreviated costume and did slapstick comedy in addition to singing the “adult songs” which Healy’s formula called for. The dancing team of Mildred and Henri regaled the audience with their intricate steps. Watching and listening to the spectacle, the Cotton Club patrons could have no doubt that they were witnessing firsthand the emergence of the primal African from beneath the sequined costumes and tan skins of the performers.

Within a few weeks the band was no longer known as the Washingtonians but as Duke Ellington’s Jungle Band. While many of Ellington’s titles from this period reflect the “jungle” motif—”Jungle Jamboree,” “Jungle Blues,” “Jungle Nights in Harlem,” “Echoes of the Jungle”—such titles were conceived as attention- and publicity getters by Ellington’s agent, Irving Mills, and had little to do with Ellington or the compositions themselves. Ellington had mixed feelings about this “Jungle Band” reputation; he was not simply catering to white tastes. “As a student of Negro history I had, in any case, a natural inclination in this direction,” he would later say. As a matter of fact, the growl style which the Ellington orchestra developed to perfection is simply a development of the “vocalization” of instrumental tone and inflection which is so characteristic of Black music.

The average Cotton Club patron would not have understood this—or cared to. What the average customer wanted was exciting, dazzling jazz, and that is what the Ellington band gave them. In the process, Ellington and his men sometimes slipped into a manner of playing that was patronizing and uninvolved, for they hadn’t the opportunity to play the fierce, creative music that the bands played at the Savoy, or the Nest Club, or Small’s Paradise, where there was a larger Black audience. Still, even playing before an audience not knowledgeable in the subtleties of jazz, there were times when the band members achieved an intimacy and a unity of feeling that could never again be duplicated. It is said that once the entire brass section of the band rose and played such an intricate and beautiful chorus that the usually poised and dignified Eddie Duchin actually rolled under the table in ecstasy.

Despite the lack of creative opportunities, Ellington welcomed the upturn that his career had taken since his arrival at the Cotton Club. And he had the club to thank for the upturn in his personal life, too. At the Cotton Club Duke Ellington had fallen in love.

It was not the first time for the amorous Duke, nor would it be the last, but at the time he was free; he had broken up with his wife, Edna Thompson Ellington. He and Edna, who was also a musician, had been high school sweethearts in Washington. They were married in 1918 and not long after, their son, Mercer, was born. A child born later died in infancy. When Ellington decided to go to New York in 1922, Edna followed him. The first years were happy and exciting, but as time went on, the two grew apart, and while they continued to love each other very much, they realized they had nothing in common. Reluctantly they broke up, and Edna went back home, taking little Mercer with her.

With Edna gone, Duke felt his aloneness keenly, and his eye for beautiful young women, always acute, sharpened even more. December 4, 1927, the night Ellington’s band opened at the Cotton Club, was also the opening night for Mildred Dixon, who was teamed in a dancing duo with Henri Wessells. Short, sleek and dark-eyed, she attracted Duke’s interest immediately, and it is likely that one reason for the band’s poor performance that opening night was Duke’s preoccupation with the beautiful dancer.

“Since he played with his feet well in front of him,” biographer Barry Ulanov reported in 1946, “and with his face turned to the audience, if he got interested in something other than the music, he could always fake the chords, just run his hands deftly over the keys and make it look right, even if he weren’t playing a note. He faked the first time he saw Mildred.” (5)

Duke and Mildred got acquainted—during rehearsals, and after Duke felt secure in his position at the Cotton Club, during shows. She was interested in what he was doing and what he was feeling, and he found himself trusting and confiding in her. Shortly thereafter Mildred left show business to become the second Mrs. Ellington.

Mildred Dixon was not the only girl in the Cotton Club show to pair up with a member of the Washingtonians. Soon after the band went into the club, drummer Sonny Greer married Millicent Cook and took her out of the chorus line.

Meanwhile the band and the club were on their way to national fame. WHW, a small local radio station, began to broadcast a nightly session of Ellington’s music from the Cotton Club, and it was not long before both band and club got a fantastic break. Columbia Broadcasting System, represented by its famous announcer Ted Husing, approached Herman Stark with the idea of broadcasting the sessions on a national basis.

Stark was cool to Husing. “There’s no money in it for me. It will do you some good, not me. However, it’ll probably do Duke some good, too, so go ahead and we’ll see what happens.” (6)

What happened was that the “Cotton Club sound” became a national smash. Before long, nearly every American who had a radio knew of the Cotton Club, and what visions of glamour and sophistication and big-city wickedness that name conjured up in their minds! A trip to Harlem, and to the Cotton Club in particular, became a “must” for every Midwesterner who visited New York City. Tourists from all over the country came flocking uptown.

Within a year Ellington had become such a prize property that the Cotton Club agreed to his request to relax the “whites only” policy. This is not to say that Ellington pushed for complete integration of the clientele, or that the club suddenly welcomed Black patrons. But Ellington had hinted that it was a shame some of his friends could not enter the club to hear him and that the families of the other performers were not permitted to watch them. The management, aware of its stake in Ellington, had cautiously acceded, at least while he was at the club. But Black customers were still carefully examined before being admitted. The complexion of the Cotton Club audience did not change radically; after all, there were not that many Harlemites who cared to patronize the new semi-Jim Crow establishment.

The white “slummers” continued to come in droves. They spent their money lavishly, for it was a time of heavy investing in the stock market, and of premium dividends. Many whites threw their money around “like there was no tomorrow,” much to the glee of the club’s staff and entertainers. Waiters hardly even considered their $1 per night salary when they spoke of their gross earnings per week. It was the tips that made life beautiful, particularly for those waiters with facility in popping champagne corks with aplomb.

The entertainers fared even better. As a member of the Cotton Club band, Sonny Greer made $45 per week in salary. However, there were ways of augmenting that quite respectable wage. “Anytime we needed a quick buck, we would push the piano up next to the table of the biggest racketeer in the joint. I would then sing ‘My Buddy’ to him. I never remember getting less than a $20 tip for such an easy five minutes’ work.” (7) Drunks were even easier to manipulate. “You’re in Harlem now,” the table singer would tell one. “You can’t give my piano player a little old dollar bill.” Naturally, the drunk would make proper amends.

“It didn’t really matter what the salary was,” Duke Ellington later remarked. “A big bookmaker like Meyer Boston would come in late and the first thing he’d do was change $20 into half dollars. Then he’d throw the whole thing at the feet of whoever was singing or playing or dancing. If you’ve ever heard $20 in halves land on a wooden floor you know what a wonderful sound it makes.” (8)

The Ellington band was making good money and getting the exposure so necessary for success. The members of the band were grateful to the Cotton Club for such opportunities and they were also quite happy at the club. They became friends with the regular Cotton Club performers, dated the girls, and sometimes married them. They also became friends with the members of the Madden gang and their associates. Owney Madden rarely presented himself at the club, preferring private parties in his penthouse apartment in Chelsea, not far from his Phoenix Central Cereal Beverage Company. In fact, he rarely left his apartment, and when he did he always rode in his bulletproof Duesenberg. However, when the Duesenberg did roll up in front of the Cotton Club, and Madden entered, escorted by his bodyguards, he was always polite, and as the members of the Ellington band would put it, straight.

“I keep hearing how bad the gangsters were,” Sonny Greer said later. “All I can say is that I wish I was still working for them. Their word was all you needed. They had been brought up with the code that you either kept your word or you got dead.” (9)

Big French DeMange was a particular fan of Ellington’s music and of Ellington himself. “Anything you want, Duke,” Frenchy liked to say, “anything you want you ask for it, and it’s yours, ” and there was no question that Big Frenchy DeMange could make good on his offer.

Frenchy loved to play cards, and often after the 2 A.M. show he and Stark and Duke and Mildred would play cards until the sun came up. First they would play whist, then pinochle, and finally, as the boys from the kitchen served their breakfast, rummy, which was easiest to play while eating and drinking. Then they would adjourn to their respective homes or quarters and go to bed.

Other evenings Duke would go alone or with some of his band members to one of the speakeasies on “the Corner,” 131st Street and Seventh Avenue. During the twenties and early thirties, this was the site of the most creative music-making in Harlem. Connie’s Inn was located there. Connie Immerman welcomed the Black musicians in the early-morning hours after they finished their stints in other clubs, and gangster Dutch Schultz showed he was more musically hip than the Madden gang by hanging out there frequently. The Band Box Club at 161 West 131st Street, run by cornetist Addington Major, was another favorite gathering place. It had no regular musical program, but plenty of music was made there. Its special rear bar became one of the most popular places for jam sessions. The Barbecue, the rib joint in Harlem, also had no regular live music. It was the first place in Harlem to have a juke box, although the new contraption really wasn’t needed. The counter was directly over the bandstand downstairs in Connie’s Inn.

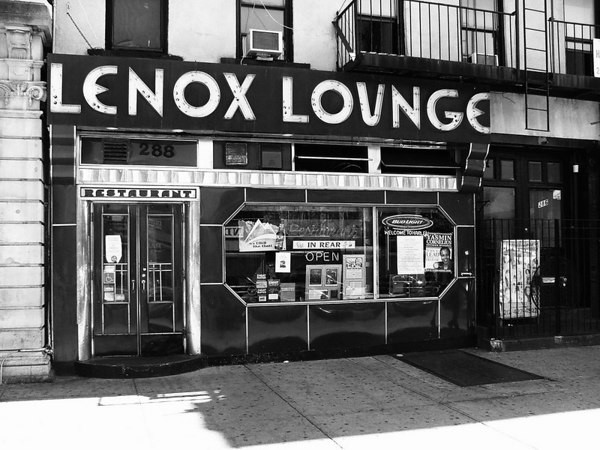

Monday mornings about five o’clock, it was customary for Cotton Club performers to go next door and upstairs to the Lenox Club, on Lenox Avenue and 144th Street, for the weekly breakfast dance. Almost every big-time act in town would be there to do its number, and it was not unusual to see Bill Robinson, Ethel Waters, Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington and Cab Calloway (who did not have his own band yet) all in one morning. In such places, Duke and the other musicians from clubs like the Cotton Club that were out of the jazz mainstream could get down to real jazz and find stimulation from other experimenters in the medium.