4 The Depression Begins

On October 23, 1929, the first blow fell on the reckless prosperity of America. The New York Stock Exchange witnessed a minor panic among stocks that speculators had pushed to fantastic heights. The next day, “Black Thursday,” saw rampant hysteria. Rumors of mass suicides attracted a crowd of spectators to Wall Street to scan the windows of the tall buildings and to gather under a scaffolding to watch an ordinary workman in morbid expectation of his plunge. Five days later, on the 29th, America realized that the 23rd had represented merely the initial, warning tremors of the crash.

American optimism did not crash along with Wall Street. The stiff-upper-lip tradition prevailed and, indeed, became official policy. New York mayor Jimmy Walker requested that movie theaters show only cheerful films. The message, “Forward America, Nothing Can Stop U.S.,” appeared on billboards across the nation. The song “Happy Days Are Here Again” was copyrighted on November 7.

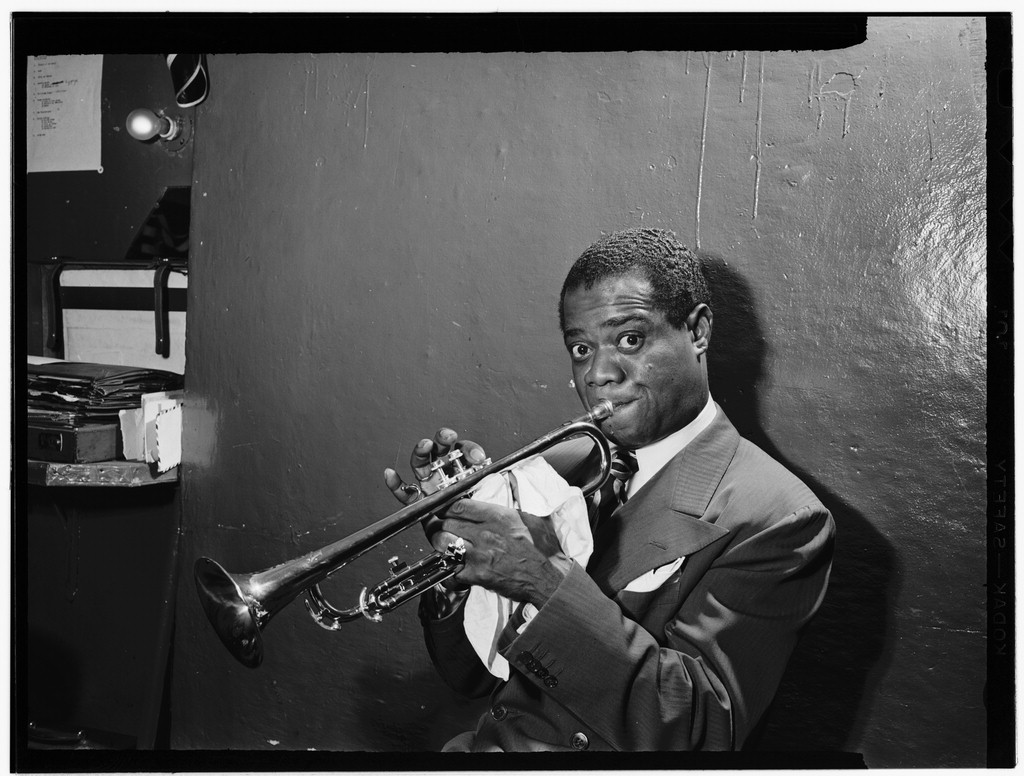

Up in Harlem, the clubs rocked as tipsily before. Connie’s Inn was entering its peak period. Louis Armstrong, with Carroll Dickerson’s orchestra in from Chicago, were attracting turn-away crowds to their Hot Chocolates show. By this time Armstrong was really in the money, and he dressed accordingly. Clarinetist Mezz Mezzrow later described his and Armstrong’s dress when they went out on the town: ” . . . oxford-gray, double-breasted suits, white silk-broadcloth shirts (Louis wore Barrymore collars for comfort when he played, with great big knots in his ties), black double-breasted, velvet-collared overcoats, formal white silk mufflers, French lisle hand-clocked socks, black custombuilt London brogues, white silk handkerchiefs tucked in the breast pockets of our suits, a derby for Louis, a light gray felt for me with the brim turned down on one side, kind of debonair and rakish.”(1) Over at the Cotton Club, Duke Ellington and his band played as gaily as ever, for their careers were skyrocketing.

In 1929 they appeared simultaneously at the Cotton Club and in Ziegfeld’s Show Girl, for which Gershwin had written the score and which introduced “An American in Paris” and “Liza.” In 1930 they first accompanied Maurice Chevalier at the Fulton Theatre and later in the summer traveled to Hollywood to appear in Check and Double Check, a film featuring the popular radio team of Amos ‘n Andy. As the latter gig could not be managed simultaneously with nightly stands at the Cotton Club, another band was hired to fill in. . .

“I was with the band in a little spot down on Broadway, the Crazy Cat Club, and they found me down there and demanded that I come to the Cotton Club the next day,” (2) Cab Calloway recently recalled. It was a great opportunity for the band to follow Ellington at the Cotton Club, although the spot was already familiar to many of the band’s members, who had played at the club as Andy Preer’s Missourians.

Calloway, who was born in Rochester, New York, had begun his musical career in Chicago, where he worked as a drummer while studying pre-law at Chicago’s Crane College. Playing in the South Side clubs attracted him much more than his studies, and Calloway went on to sing, first with Louis Armstrong’s Chicago band, and then with Marion Hardy’s Alabamians, a band in Chicago that included trumpeter Eddie Mallory and bassist Charlie ” Fat Man” Turner.

In the winter of 1928–1929, the band traveled to New York to play at the Savoy Ballroom. While there, Calloway and Hardy fought so bitterly about who was to be billed as leader that when the Savoy con tract was up, the two split. The Alabamians went to Connie’s Inn, and Calloway himself was temporarily out of a band.

This situation was not to last for long. Irving Mills, Calloway’s agent as well as Duke Ellington’s, suggested that Calloway team up with Andy Preer’s old band. Calloway needed a band, and the Missourians, who had done little since leaving the Cotton Club, needed an exciting leader.

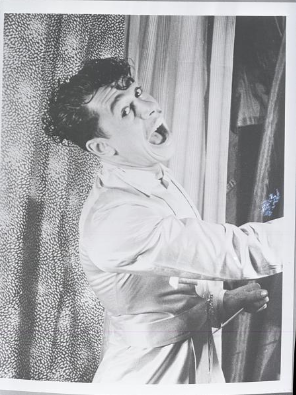

Calloway was that, and in fact at first he was something of a shock to the veteran band members. From the first downbeat to the last note of a number, he was all motion. He waved his arms, he ran back and forth from orchestra to microphone, he danced in a frenzy to the music. His hair flew one way, his coattails another. The first time the Missourians played with him they were so startled at his performance that it’s amazing they missed no notes. Cab Calloway in action was really something to see.

The audience loved it. The tension—wondering whether or not he was going to crash into the band or the microphone—only heightened the excitement of watching him perform. Once he actually fell off a stage and broke his ankle.

Cab Calloway changed the Missourians from a background orchestra to an act in their own right, and Irving Mills had little trouble booking them into the Cotton Club as a replacement for Ellington’s band. The club’s popularity continued undiminished despite Ellington’s absence, for Calloway was a one-man attraction. Lucky for Calloway that he was so popular with audiences, including the Cotton Club patrons; otherwise his first engagement at the club might well have been his last. He pulled an historic boner on, of all nights, a Sunday, a “celebrity night,” broadcast all over the area. As a Chicago columnist recalled the incident:

Healy had a benefit to play one Sunday night. . . But Dan couldn’t get up to the Cotton Club for his usual stint, so the introductory task fell to the lot of the band leader, Cab Calloway. This was Cab’s first engagement at the Cotton Club, and he hadn’t acquired the savoir faire and the ability to ad lib which came to him in later years of experience at a microphone.

On this particular evening one of the world’s most famous and beloved songwriters, Irving Berlin, was a guest at the club. He rarely was, or is, seen in night clubs and always has had the reputation of being a retiring, shy individual who shuns spotlights and anything savoring of notoriety or acclaim. His sincere modesty never has been questioned.

At his table were Oscar Levant, a pianist who frequently was Berlin’s companion in that era, and Mrs. Levant. Mrs. Berlin, the former Ellin MacKay, never was seen with her husband on his own infrequent appearances in night spots.

A list of the guests present was prepared on cards by the head waiter, the captains and others, as usual, and presented to Calloway for his guidance in making the introductions. Cab got along fine for the first few moments, even slipping in a typical Healy compliment to some one’s talent now and then.

Then he introduced Mr. and Mrs. Irving Berlin!

Necks craned in all directions, because the professional crowd there never had seen Mrs. Berlin in public. The head waiter and the captains got frantic, and Herman Stark, the manager, came charging out of his private office.

Before they could signal His Highness of Hide-ho, he already had introduced Oscar Levant at Berlin’s table, and neither of them would arise to acknowledge the introduction.

Finally Kid Griffin, the suave custodian of the portals, called Calloway to the side of the floor and slipped him a card rectifying the error.

Cab returned to the microphone and apologized to his audience, to the listeners on the air as well as to the other guests in the club.

“It seems I made a very serious error in my last introduction,” he explained.

“The lady with Mr. Berlin is not his wife!” That halted the broadcast and the introductions for the evening. Dan Healy came back the following Sunday night. (3)

Ellington and his band returned to the Cotton Club early in 1930, after finishing their stint in Hollywood with Amos ‘n Andy’s Check and Double-Check. As Calloway and his band had been hired merely to fill in while Ellington was away, naturally they were expected to leave and find another job. However, they were not expected to go to a rival club, and when they were signed on at the Plantation Club, the Cotton Club people were highly displeased.

The Plantation Club, at West 126th Street near Lenox Avenue, was an uptown branch of the successful Plantation Club on Broadway at Fiftieth Street, where Florence Mills, among other stars, had been featured. It was no secret that the uptown Plantation Club had been opened to draw away some of the Cotton Club’s lucrative business. Calloway had done very well for the Cotton Club, and it was hoped that some of Calloway’s fans would follow him to the Plantation sixteen blocks farther downtown.

One night the Plantation had unexpected and uninvited guests. “Some of the boys” smashed chairs and tables, shattered glasses and bottles, uprooted the bar and planted it on the curb outside. They reduced the place to such a shambles that it took months of work and thousands of dollars to put it back together. While no one around town cared to be quoted about the incident, word was out that Owney Madden’s gang just might have had something to do with it. Early one morning a few weeks later, Harry Block’s bullet-riddled body was found in the elevator of his apartment building. Although it was never proved, the story was that Block’s murder was a direct result of the wrecking of the Plantation Club, which never did reopen.

In 1930 Jimmy McHugh and Dorothy Fields left the Cotton Club to go on to major prominence. While at the club, they had done other work on the side. In late 1927 they had produced “I Can’t Give You Anything But Love” which became a hit in Lew Leslie’s Blackbirds of 1928 on Broadway, and in 1930 they were doing the score for The International Revue. In succeeding years they wrote such well-known songs as “On the Sunny Side of the Street,” “I’m in the Mood for Love,” “Lovely to Look At” and “Don’t Blame Me.” While they were grateful to the Cotton Club for helping to give them their start, both McHugh and Fields were glad to leave. Despite the solicitous treatment she received, Dorothy Fields in particular had frequently been disgruntled there and had often refused to sign her name to some of the more “earthy” songs she was expected to do.

Their successors at the club felt much the same way and refused to allow many of the adult songs they were required to write to be either recorded or copyrighted.

Harold Arlen, composer, and Ted Koehler, lyricist, had already become popular as the producers of the song “Get Happy,” introduced by Ruth Etting in The 9:15 Revue in 1930. Like Dan Healy, they came to the Cotton Club from the downtown Madden-controlled spot the Silver Slipper. Healy needed songwriters for the club’s fall 1930 show, Brown Sugar—Sweet, But Unrefined, and Arlen and Koehler were available, so they signed on at a salary of $50 a week plus all the food they could eat. The salary was meager, but the two songwriters were happy to have the chance to write for a club whose productions were as close to Broadway as one could get without actually being on the Great White Way.

Clearly, there is no such thing as a “winning” songwriting method. Each individual and each team of songwriters has a particular style, but Arlen and Koehler’s, especially Koehler’s, was so casual and matter-of-fact that it is difficult to realize what thought and talent went into the works they produced. Usually Arlen would begin the process by writing a rough draft of the music. Then he would go to the piano and play it, over and over, polishing it. Meanwhile Koehler would be stretched out on a couch, listening, thinking. Sometimes he would appear to doze and Arlen, feeling he was working harder than his partner, would shout at him to wake him up. Immediately Koehler would snap to attention, tapping his feet and whistling to prove he was listening. As time went on, Arlen came to realize that Koehler was indeed working, for the completed lyric was always perfect for the tune. Koehler’s theory was that lyrics came naturally and would not work if they were contrived. He simply didn’t believe in “wasting his cells.”

Among other physical activities in which Koehler did not like to engage was walking, although sometimes Arlen was able to talk him into doing so. One day in the winter of 1930-1931, Arlen persuaded Koehler to walk from the Croyden Hotel on Madison Avenue and Eighty-sixth Street, where Arlen lived, down to their publishers’ office in midtown. The air was chilly, and before long Koehler began to complain and to make suggestions like “Why don’t you join the Army if you love to walk so much?” Laughing at his friend’s complaints, Arlen began to hum a marching tune, and in spite of himself Koehler fell into step and into the mood. By the time they reached Forty-seventh Street, “I Love a Parade” was nearly written.

By the end of 1930 the Cotton Club life had begun to pall for Duke Ellington. He felt cramped in his style. He was tired of playing show tunes. He had to admit that the people at the Cotton Club were good about letting the band off to play outside gigs, but he needed a real change. He needed to get back in touch with his music. He and his band left the club.

Cab Calloway’s band took over as the Cotton Club band, apparently harboring no hard feelings about the forced termination of their stint at the ill-fated Plantation Club. Just prior to coming back to the Cotton Club, they had played a very successful gig at the Alhambra Ballroom, breaking all former attendance records at the spot. Also, they had recently recorded the first of their big successes, “St. James Infirmary,” with Brunswick Records. For old Missourians such as trumpeters R. O. Dickerson, Lamar Wright and Reuben Reeves, trombonists DePriest Wheeler and Harry White, saxophonists Billy Blue, Andy Brown and Walter Thomas, pianist Earl Prince, banjoist Charley Stamps, bassist Jimmy Smith, and drummer LeRoy Maxey, it was about time. Compared with them, Calloway was a relative newcomer, but he welcomed this, the band’s first extended engagement at the Cotton Club as much as they did. And well he might have, for it proved the real “making” of Calloway and his band.

The Cotton Club management hired Clarence Robinson to create and stage the spring 1931 show. Apparently there also existed no hard feelings on Robinson’s part over the “muscle” the Madden gang had used to get him to release Ellington and his band from their contract at Gibson’s Standard Theatre in Philadelphia back in 1927, What made his employment particularly notable was that it was the first time the job was given to a Black. The show, Rhythmania, opened in March and was the most successful to date. It included Arlen and Koehler’s “I Love a Parade,” for which Healy devised a spectacular routine complete with batons and fancy stepping, Blues singer Aida Ward introduced their song “Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea,” and Cab Calloway’s specialties were “Trickeration” and “Kickin’ the Gong Around” which, with “Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea,” were among the year’s hits. In night-club history, however, this show would be overshadowed by the club’s fall revue that year. It was the second 1931 show which catapulted Calloway to fame.

On the whole, there was nothing particularly memorable about the show. Cora LaRedd did her famous trick dancing, and Swan and Lee contributed their intricate team steps, Aida Ward and Leitha Hill sang their traditional torch songs. Arlen and Koehler’s work was respectable but not particularly exciting, The real hit of the show was a number written and performed by Calloway in his own inimitable style. “Minnie the Moocher,” a “low-down, hootchie-cootcher,” practically became a folk character.

“My manager, Irving Mills, and I were sitting around the old Cotton Club in New York tossing phrases at each other,” Calloway later recalled, “and ‘Minnie the Moocher’ came up. We banged out the lyrics and melody on the spot and tried it out a couple nights later. It went over big,” That is an understatement. The night the song was introduced, the Cotton Club audience demanded six encores!

“Sometime after that,” Calloway continued, “I didn’t have my mind on my work while I was on the bandstand and in the middle of ‘Minnie’ I forgot the lyrics, so I yelled ‘hi-de-ho’ instead and the band took it up and then the customers. Out of that song I got a hit tune, a big-selling record, an offer of better jobs and a trademark—’hi-de-ho.'” (4)

The band became known as the “hi-de-ho” band, and for the next twenty years Calloway was known as the “hi-de-ho” man.

Hi-de-ho. It was merely a scatting of a song’s lyrics, but it expressed the feeling of the times, the reckless gaiety of a society that refused to recognize that the economic bottom had fallen through. Anyone reading the society columns or frequenting the night spots would find it hard to believe that a Depression was going on. The dancers moved with the same abandon, and the conversation was as animated as ever. These young gadabouts, these wealthy white patrons, these favored Black entertainers had not yet been touched by the Depression. They danced on, carried the momentum of earlier prosperity. For them the twenties had passed into the thirties rather smoothly, and they saw no reason to greet the new decade with any other attitude than the cynical, worldly abandon with which they had related to the old. That year, 1931, saw the opening of the world’s finest luxury hotel, the new Waldorf-Astoria. The tallest building in the world, the Empire State Building, was completed. In the same year the architects’ plans for Rockefeller Center were published. The entertainment industry as a whole did not feel the effects of the crash for some time. In fact, initially, it benefited. People turned to commercial entertainment to help them forget their troubles or to help delay the realization of their troubles. The hit song of 1931 was “Life Is Just a Bowl of Cherries,” and nothing epitomized that attitude more than the nightly mood at the Cotton Club.

The club had become the favorite late-night spot of the fast set, which in those pre-jet days was called the Mink Set. Financier Otto Kahn was often there, as was Mayor Jimmy Walker (the club was officially on the mayor’s Reception Committee list and was famed for its foreign visitors); showbusiness personalities, bankers, Texas cattle barons, the youngsters of both old and new monied families. They gave class to the Cotton Club, which gave them social standing in return. Opening nights at the club were as exciting and celebrity-studded as any Broadway premiere. All the important columnists were there, men like Walter Winchell and Louis Sobol and Ed Sullivan. Americans across the country sat glued to their radios, listening to Ted Husing’s coverage of the events just as, later, Americans would sit transfixed at their television sets watching the Academy Awards.

The show people who came uptown after an evening entertaining an audience to be entertained themselves were frequently asked to contribute their talents on an impromptu basis. One of Dan Healy’s cleverest ideas was to inaugurate Sunday “celebrity nights,” and on a given Sunday evening one was quite likely to see Marilyn Miller do a soft-shoe, or Helen Morgan sing a tearful song. On Sunday night the Cotton Club Girls wore their best finery and paraded past the celebrities’ tables after the show, hoping to be noticed. Invariably, they were. Like the waiters, the Cotton Club Girls played their role to the hilt, exuding an aura of glamour, living proof of the club’s advertisement—”Tall, Tan and Terrific.”

Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., sufficiently light-complexioned to gain admittance to the Cotton Club even in the early days, met his first wife, Isabel Washington, when she was a Cotton Club Girl. Adelaide Marshall met her wealthy husband at the club. At least three other girls did the same, but were so light-skinned that they passed into white society.

On Sunday nights a number of young hopefuls who would frequent any celebrity spot where there was a possibility of being “discovered” could be found at the Cotton Club. Powell recalled in his auto biography:

. . . I remember sitting in the Cotton Club when it was uptown and owned by the mob. A keenlooking, handsome fellow was hanging around in those days. He was a friend of but not part of the mob that controlled the underworld of New York. He was interested in show business but couldn’t seem to get anywhere at that time, and in order to pick up a quarter here and there, and to bask in the lights of glamour, he hung around the Cotton Club. One night backstage I asked him to go out and get something for one of the girls, and when he came back I gave him a half dollar. His name was George Raft. (5)

Money flowed as freely at the Cotton Club as “Madden’s No. 1” beer. The club’s philosophy was: We spare no expense for the comfort of our customers, and our customers spare no expense to have a good time. To pay for the forty entertainers in the lavish shows, staged at an average weekly cost of $4,000, the club charged exorbitant prices by the average person’s standards, beginning with a $2.50 cover charge. At $1, a bottle of Madden’s beer was quite reasonable, and the prices of mixers encouraged customers to order it, or discouraged them from drinking the liquor they had brought with them. A glass of orange juice cost $1.25, a quart of lemonade $3.50, a tiny bottle of ginger ale cost $1. Even milk was 50 cents.

Food prices were comparable to those in other cabarets. A steak sandwich was $1.25, as was the plate of scrambled eggs and sausage. Lobster and crabmeat cocktails could be ordered for $1. A side order of olives was 50 cents. The Chinese soups were all 50 cents each, and the most expensive Chinese main dish, Moo Goo Guy Pan, was $2.25. While the Cotton Club did not net a lot from its sale of food, its cover charge and beverage sales produced a healthy profit, which was fortunate for the Madden people, who once found it necessary to pay out a large portion of those profits to ransom Big Frenchy.

About 1930 occurred the first real trouble among the gangsters that was to lead to the end of the Harlem era. While Owney Madden controlled the bootleg business in Manhattan, the Bronx business was in the hands of Arthur Flegenheimer, more widely known as Dutch Schultz. One of Schultz’s lieutenants was a young man named Coll. The story goes that Schultz and Coll had a falling-out and Coll was “hit” by Schultz’s men. Coll’s younger brother, Vincent, better known as “The Mick,” determined to avenge his brother’s death, He hit a couple of Schultz’s men and then boldly announced that he was merely working his way up to the top.

The New York underworld was unprepared for the likes of Vincent Coll. Certainly they were no strangers to murder, but it was of the orderly kind, involving conferences and votes and contracts. Vincent Coll defied all the rules. It was not long before “The Mick” became known as “Mad Dog. ” Then “Mad Dog” went too far. Gunning for another of Schultz’s men on a Harlem street, he killed a five-year-old boy instead and wounded other children as they played. He made front-page headlines as “The Baby Killer,” and then the police were after him.

Up against both the mob and the law, “Mad Dog” grew desperate. He’d attracted a fairly large coterie of reckless young hoods, so he didn’t lack manpower. What he needed was money, and in one of the boldest moves in New York gang land history, he kidnapped George “Big Frenchy” DeMange and George Immerman, Connie (Connie’s Inn) lmmerman’s brother, and held them for ransom.

“He was looking to snatch me,” Connie Immerman later reported, “but I wasn’t in the joint that night and they took George instead. It was funny about The Mick. He phoned me and assured me that George was all right. He said that George had some money on him, that it would be taken, and George would be released. But I was to get together the difference between what George had and $20,000 and have it ready with the doorman at Connie’s on a certain night.” (6)

Meanwhile DeMange sent word to Madden that Coll wanted a higher sum, $35,000 according to one story, $50,000 by another, for his return. Madden paid. Both hostages were released, and the corpulent Frenchy’s return to the Cotton Club was an occasion of great celebration.

The safe return of George and Frenchy did not end the matter, which was the way of some gangster troubles. Wars between mobs often ended in a truce, and differences were theoretically forgotten. But when one of the combatants was an individual, and one who did not play by the rules at that, the end was more direct and final. In 1932 “Mad Dog” Coll was ambushed in a telephone booth on Twenty-Third Street in New York’s Chelsea district by two machine-gun-packing lieutenants of Dutch Schultz.

The incident had no effect on the Cotton Club’s business. It had taken place away from the club and did not directly involve it. Most of the patrons never even knew about what had happened. In view of the club’s management, it is surprising that there were never any typically gangland incidents at the club in the mobster’s heyday that was Prohibition.

In 1932 another of the rigid color standards maintained at the Cotton Club was relaxed—the one governing selection of Cotton Club Girls. The “whites only” admission policy had been eased some four years earlier, enabling relatives and friends of performers as well as important Blacks to enter, although they were frequently seated at back tables near the kitchen. The policy of hiring only light-complexioned chorus girls—”nothing darker than a light olive tint”—had seemed unassailable. Yet in 1932 Lucille Wilson did challenge it, and she won. She displayed talent and guts during her audition and charmed Harold Arlen, among others. The Cotton Club management, challenged to come up with a rational reason why they should not at least give her a try, failed to do so.

Lucille Wilson was hired on a trial basis. If the customers complained, she was out. But the customers did not complain, and Lucille, who later became Mrs. Louis Armstrong, remained with the Cotton Club for eight years.

In 1932, there was a number of rent parties in Harlem. A peculiarly Harlem institution, rent parties had begun when the busy war industries lured Southern Blacks to New York City and slick landlords realized these newcomers would pay the most exorbitant rents in order to have a place to stay. Now that the Depression was on, paying the rent became an even greater struggle. Practically wherever one went in Harlem one was amused or beguiled by countless hand-lettered announcements promising good food and fine entertainment in return for a contribution to the monthly rent bill. While part of the money taken in went to pay for entertainment and refreshments, a successful rent party usually took care of the rent, and sometimes there was a little money left over.

Arlen and Koehler, particularly Arlen, were sensitive to the world outside the Cotton Club, and they quite frequently recorded local cultural traits in their songs. Partly this practice was good business, for the club’s patrons were curious about the world of Harlem and responded to songs that seemed to give them an “inside look” at that world. But partly, too, these songs were an expression of Arlen’s real feeling for Harlem and its people. They struck a responsive chord in the soul of this man born Hyman Arluck in Buffalo, New York, the son of a cantor.

Ethel Waters is supposed to have called him “the Negro-ist white man” she had ever known. Songwriter Roger Edens recalled going with Arlen to the Cotton Club and watching him rehearse with the cast:

He was really one of them. He had absorbed so much from them—their idiom, their tonalities, their phrasing, their rhythms—he was able to establish a warming rapport with them. The Negroes in New York at that time were possibly not as sensitive about themselves as they are today. But even so, they had a fierce insularity and dignity within themselves that resented the so-called “professional Southernism” that was rampant in New York in those days. I was always amazed that they completely accepted Harold and his super-minstrel-show antics. They loved it—and adored him. (7)

Some of the songs Arlen and Koehler wrote for the club in 1932 (starting with that year, the shows were called Cotton Club Parades) reflect their ability to produce material expressive of local cultural traits, both attractive (“Harlem Holiday”) and unattractive (“The Wail of the Reefer Man”). They also faithfully reproduced Black genre songs, such as the blue blues for which Bessie Smith and Ethel Waters were noted. Leitha Hill was the torch singer in residence at the club at that time, and for her, Arlen and Koehler produced such songs as “Pool Room Papa,” “My Military Man” and “High Flyin’ Man.” None of these songs bears Arlen’s name. They were the sort of shocking songs that could’ be found only on “race records,” and as such, Arlen felt they were a bit too “specialized.”

The song Arlen and Koehler wrote for the club in 1932 that became a national hit was “I’ve Got the World on a String,” which Aida Ward sang in the show. Other numbers included “In the Silence of the Night,” “That’s What I Hate About Love” and “New Kind of Rhythm.” And for Cab Calloway, and the Cotton Club audience, a return of that favorite club personality in “Minnie the Moocher’s Wedding Day.”

Owney Madden usually showed up on opening nights, or a few nights after an opening, but he was not around for the fall 1932 show. In July he had voluntarily reentered Sing Sing. Ostensibly the action was taken because of a parole violation, but since only a minor technicality was in question, Madden clearly wanted to be back in prison. Although his exact reasons are not known, it is likely that he was tired of being a mob leader and wanted to retire. Returning to prison may have been a way of “clearing up” his 1916 sentence. Also, he may have felt that being in prison, he would be treated more leniently by the Internal Revenue Service. In May of 1933, from prison, he requested an easement on his income taxes for 1931, in which there was an alleged deficiency of $20,493. He’d been having trouble with the IRS since 1924, yet between that year and 1931, claims on him by the government had totaled only $70,000. As Madden had accumulated considerable wealth through his various rackets, it is certain that he had a very clever tax lawyer in Joseph Shalleek. The theory that Madden re-entered Sing Sing primarily in order to clear up loose ends in his relationship both with the courts and with the IRS is supported by the fact that upon his release from prison later in 1933, he went into retirement in Hot Springs, Arkansas.