5 Prohibition is Repealed and the Depression Deepens

In January 1933 the proposed constitutional amendment for repeal of Prohibition went to the states for ratification, and apparently confirmation was so certain that the next month beer returned legally, a “fore-taste,” as one writer put it, of things to come.

Repeal was greeted with mixed feelings in New York. Obtaining bootleg liquor, no matter how easily it could be done, did involve a bit of daring and bravado, and the partying crowd bemoaned legitimization. Syndicates like Owney Madden’s now faced government crackdowns of far greater strength than during the period of Prohibition, and those who had opened clubs as outlets for their bootleg products feared that the combination of Depression and repeal would be extremely bad for business. That fear proved real for a number of Harlem night spots, which closed that year. Connie’s Inn, one of the Harlem “Big Three,” left Harlem to the remaining “Big Two” and moved to greener pastures downtown.

By 1933 the effects of the Depression had taken their toll upon the mood as well as the pocketbook of the country. As average annual per capita income tumbled from $681 in 1929 to $495 in 1933, the optimistic view that the Depression would be over almost as soon as it began had been replaced by a more realistic attitude. The popular song of 1932 was “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?” While the regular clientele of the Cotton Club seems not to have been seriously affected by the effects of the stock-market crash, and while the entertainers seemed as gay as ever, they could hardly miss the long free-soup lines, the beggars on the corners, the gloom that descended over the streets of Harlem. The performers began to discuss openly the ironic contrast between the places where they lived and the place where they worked. Accordingly, the Cotton Club became civic-minded.

In December 1932, the club began passing out Christmas baskets to the needy. The gesture received wide publicity, for the management always made sure that at least one of its top stars helped in doling out the baskets. New York’s social consciousness, in the institutional sense, did not develop until later, and for a while the Cotton Club conducted the largest free kitchen in Harlem.

In the late winter of 1933, business was booming at the club, partly due to an influx of former patrons of the Harlem Connie’s Inn, and the management could look forward to even higher receipts in the spring, for after two years of recording stints and playing to sellout audiences as the Cotton Club Band, Duke Ellington and his orchestra were returning in March and would be at the club for the spring show, set to open April 6th. The club’s management could count on the success of that show, for Ellington and company would ensure it, but they had no way of foreseeing what a sensation Ethel Waters would be.

When Ethel Waters had arrived back in New York in 1930, after playing one-night stands in a variety of cities, Herman Stark had staged an “Ethel Waters Night. ” This had endeared the club to her. She was not yet a star, although she was fairly well known on the entertainment circuit. She had that indefinable “something” that everyone in show business talks about but no one ever tries to explain, and she had possessed that quality from the very beginning.

Ethel Waters had begun her career in New York some years prior to 1930 at Edmond’s, on Fifth Avenue and 130th Street. It was a basement dive, patronized by pimps, hookers and gamblers and given to “pansy” fashion parades. Waters later described it as “the last stop on the way down.” Most entertainers, particularly singers, had a hard time at Edmond’s. They exhausted themselves trying to be heard above the inattentive din of conversation. Often they simply stopped trying. Not Ethel, as she was simply known. The tall brownskinned girl had presence. When it came time for her number she would stride to the center of the floor, strike a nonchalant and half-contemptuous pose, and wait. Soon all became silent, and they would remain silent and attentive as she sang the blues, infusing it with her own particular style, bringing to reality its potential for tragedy and heartbreak. There was no doubt that Ethel was an original, and it was not long before she left Edmond’s to go on to better things.

By early 1933, when she returned to New York once again, Ethel Waters’ personal life was at an ebb. She and her second husband, Eddie Matthews, had just broken up. Her career, too, was at a standstill. She’d been playing stints in Chicago and Cicero—Al Capone territory. In fact, the club at which she had sung in Cicero was one of Capone’s. Working in Capone-controlled clubs tended to “mark” performers, and to make other club owners wary of hiring them. Also, such work was rather nerveracking. As Ethel Waters would later say, ” . . . though I’m a child of the underworld I must say that I prefer working for people who never laid eyes on an Italian pineapple or a sawed-off shotgun. I went back to New York glad to be alive.” (1)

For Herman Stark, Ethel Waters’ return to New York seemed like the proverbial perfect timing. Arlen and Koehler had written a potentially exciting number for the new Cotton Club show, for which the Ellington band had created special storm effects. Ethel was just the woman to give it the rendition it deserved. It was a torch song, and Ethel had a solid reputation for doing such numbers in her own, very personal way.

Ethel was pleased that Stark wanted her, but even though she sorely needed expo sure in a club whose underworld backing was at least less conspicuous than that of the club in which she had been working in Illinois, she was sure of her talent and appeal. She was not one to “sell herself cheap.” She asked for the highest salary Stark had ever paid a star.

For his part, Stark knew he needed a particular type of performer and a particular type of voice, and he was a sufficiently good businessman to be willing to pay for what he wanted.

The song about which everyone at the Cotton Club was so excited had been created in such an offhand manner that few could have foreseen the impact it would have. Arlen had been thinking of Cab Calloway when he wrote it, but the lyrics Ted Koehler had written for the tune were not Calloway lyrics. In radical departure from his usual style, Koehler only listened to the tune a few times before he had the words. Altogether the creative process for the song took about thirty minutes, after which the two went out to get a sandwich. Running through it again later, Arlen and Koehler began to hear in the song more than what they had so casually wrought, and when they rehearsed it at the club the response was more excited than it had been to any of their earlier hits; this was A SONG!

Ethel listened to the number and agreed that it was indeed wonderful. But she felt that the piece should express more human emotion and not rely upon complex sound effects. She asked to take the lead sheet home and work on it.

When she returned, Ethel made a stipulation. She had worked on the song and knew she could infuse it with the emotion she felt it deserved, but she wished to sing it only at one show a night. The song was “Stormy Weather.”

The success of Ethel and “Stormy Weather” tended to obscure the rest of this, the twenty-second of the Cotton Club shows, which was a masterpiece of its kind, featuring eighteen scenes in addition to the Ellington orchestra’s overture, finale and interim tunes. The first scene was entitled “Harlem Hospital,” a typical vaudeville skit with a sensual twist featuring Sally Goodings as Head Nurse, Dusty Fletcher as Dr. Jones, Cora LaRedd as Doctor’s Assistant and George Dewey Washington (who was also appearing in the Broadway production of Strike Me Pink, starring Jimmy Durante), as Mr. Cotton Club.

In the second scene Washington reappeared to sing “Calico Days.” The song “Happy As the Day Is Long” was used in the skit titled “Harlem Spirit,” as was the song “Raisin’ the Rent.” Cora LaRedd and Henry “Rubber Legs” Williams did their specialty dances, and Sally Goodings sang the expected adult number, “I’m Lookin’ for Another Handy Man.”

But then came the eleventh scene, and it managed to eclipse all that had gone before and all that would come after. It was titled “Cabin in the Cotton Club” and the set was uncommonly simple—a log-cabin backdrop and a single lamppost. As the scene opened, Ethel Waters leaned against the lamppost, a lone deep-blue spotlight on her. After she sang “Stormy Weather” alone, the scene faded softly into the next, in which George Dewey Washington and the choir sang responses to her choruses. With the help of special lighting effects, the female dancers were blended into the tableau to dance to the tune of the song. The entire production was so effectively presented, so movingly performed that the audience, at first silenced, filled the room with a thunderous applause as they recovered. On opening night there were at least a dozen encores.

Other scenes followed—dances, skits, specialty acts, and then, the grand finale. It was a long show, but it moved well; the costumes were lavish, the scenery perfect, the talent marvelous. But it was the eleventh scene that people talked about, and came especially to see.

Years later Ethel Waters explained: “‘Stormy Weather’ was the perfect expression of my mood, and I found release in singing it each evening. When I got out there in the middle of the Cotton Club floor, I was telling things I couldn’t frame in words. I was singing the story of my misery and confusion, of the misunderstandings in my life I couldn’t straighten out, the story of wrongs and outrages done to me by people I had loved and trusted.” (2) “If there’s anything I owe Eddie Matthews,” she would sometimes comment ruefully, “it’s that he enabled me to do one hell of a job on the song ‘Stormy Weather.’ ”

The “Stormy Weather Show,” as it came to be called, was one of the most successful ever staged at the Cotton Club. Within a few days the song and the singer were the talk of New York, the message carried by the newspaper columnists as well as by word of mouth, specifically by such people as: Jimmy Durante, Milton Berle, Lillian Roth, Eleanor Holm, Lew Diamond, Steve Trilling, George Raft (who had “made it” by then), Fannie Ward, Eddie Duchin, Ray Bolger, Wilma Cox, Ruby Bloom, Mary Lou Dix and Bert Lahr.

People who rarely made the night club scene did so now. People who had never before visited the Cotton Club came to see the show. Irving Berlin did not often visit New York’s spots, but he had heard about Ethel Waters and “Stormy Weather,” and he traveled to Harlem to hear her sing. Berlin was writing the music for a new revue that Sam H. Harris was producing and he wanted to inject a serious note into it. After hearing Ethel Waters at the Cotton Club, Berlin knew that she was the one to do it.

Rehearsals for Berlin’s revue began two weeks after Ethel closed at the Cotton Club. As Thousands Cheer was a hit on Broadway, and Ethel Waters’ career took off. She would always credit “Stormy Weather” as the turning point in her career. Later she would have occasion to thank Arlen again, for writing “Happiness Is Just a Thing Called Joe.”

Within a few weeks after the show’s opening, “Stormy Weather” was selling fantastically well on records and sheet music, and it occurred to a young advertiser/promoter named Robert Wachsman that a vaudeville act could be built around the song. He visited Arlen and persuaded him to audition at Radio City Music Hall, where he was offered a ten-to-twelve-week contract. All he needed was the club’s permission to use the song.

When Wachsman approached him a few days later, Stark reacted negatively. “Stormy Weather” was still current in the club’s show, and Stark felt that using the song simultaneously in vaudeville would hurt the show. However, he left the final decision up to Big Frenchy DeMange. That night Wachsman returned to the club with Arlen, but Big Frenchy was nowhere to be found. They waited all night, and finally, around seven, he appeared for breakfast. Taking a deep breath, Wachsman launched into the most fast-talking and persuasive argument he could muster. Far from hurting the Cotton Club show, he insisted, using “Stormy Weather” at Radio City would attract patrons to the club. Big Frenchy did not appear to pay much attention to Wachsman, and when the promoter finished speaking, he was greeted with silence. “Well,” Wachsman asked in frustration, “What do you think?”

“I t’ink it’s de nuts,” said Big Frenchy, “Where’s my ham an’ eggs?” (3)

Permission was granted, and the “Stormy Weather” act opened at Radio City. However, it is likely that it would have been staged even without the club’s permission, for Radio City had arranged for the purchase of a special wind machine even before Arlen auditioned for the management of the Music Hall.

Each year there was a substantial turnover within the Cotton Club cast. Featured performers, naturally, did only one show, or at the most two. The chorus dancers and singers generally stayed for at least a year, and some for several. However, after the closing of each show, a few performers always left. Turnover was particularly high among the Cotton Club Girls, some of whom, like Isabel Washington, left to pursue major show-business careers of their own. Others never gained great renown, but if they had played even one season at the club, the billing “Formerly of the Cotton Club” earned them bookings at theaters and lesser clubs. Still others, and perhaps most who left, did so to get married. After the closing of the second Cotton Club Parade, the “Stormy Weather Show,” there were several places in the chorus line to be filled.

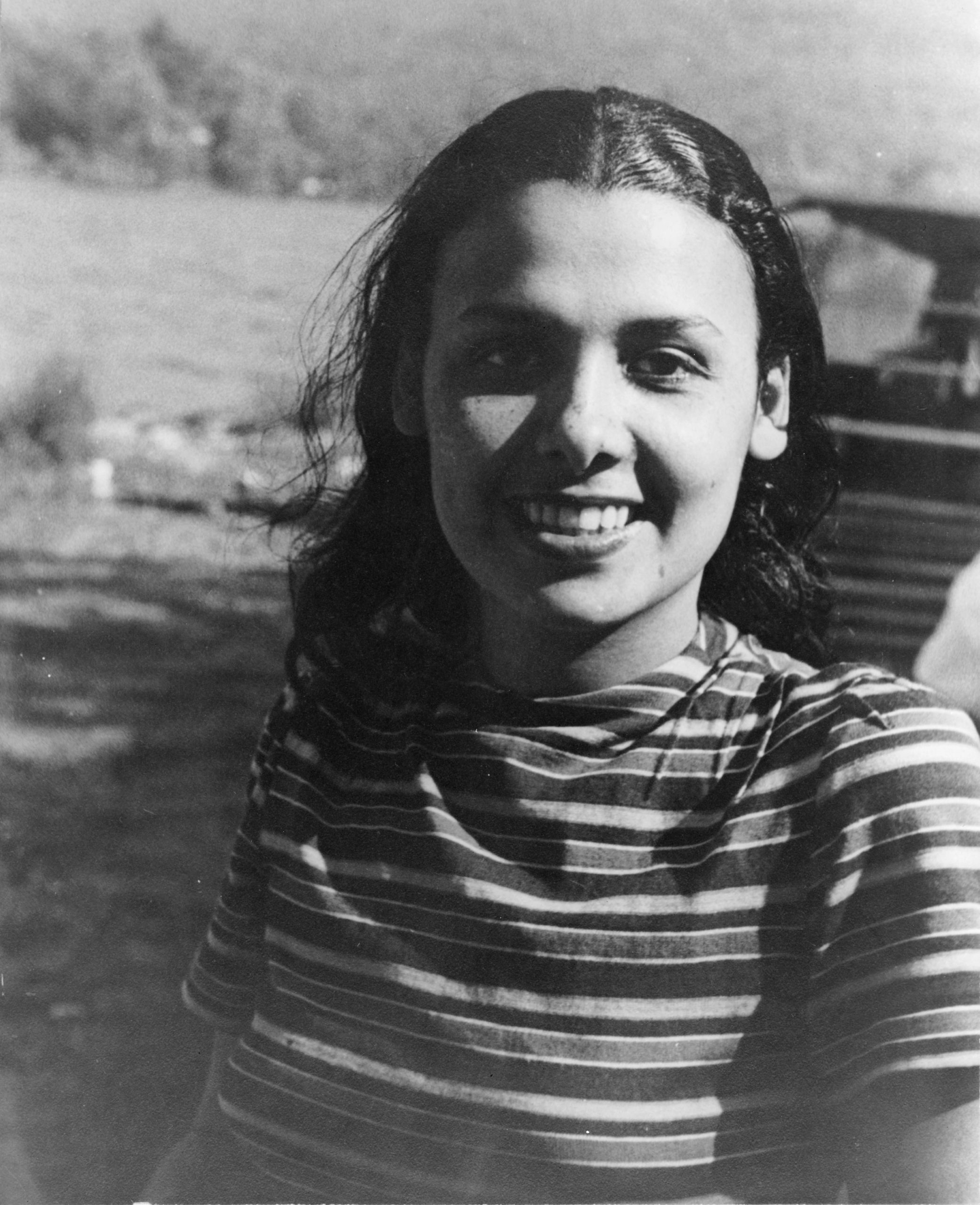

Lena Horne auditioned for one of them. Lena was from Brooklyn, by way of the Bronx and the South, and she was barely sixteen years old. During the height of the Depression, her mother, who was “of good family, ” and her stepfather were unable to earn enough money to support the family. Partly in economic desperation, and partly because she herself had tried and failed in show business, Lena’s mother decided to try to get Lena into the Cotton Club chorus line. She had known Elida Webb, dance mistress at the club, for years.

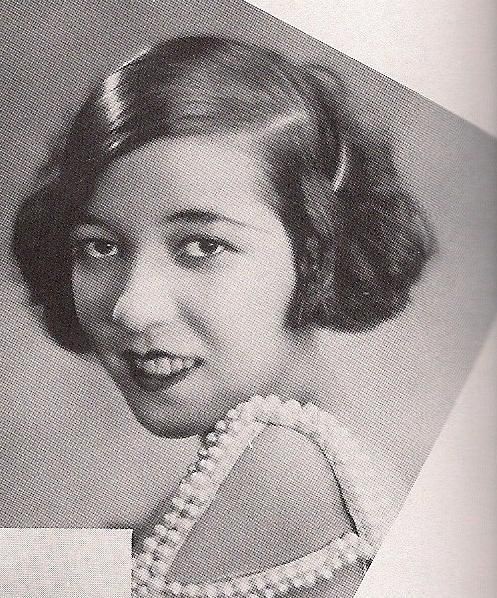

Elida Webb and Lena Horne’s mother had tried to break into show business at the same time, and while Mrs. Horne had not made it, Miss Webb had—as choreographer. As a dancer, she had been a member of the chorus line in Shuffle Along, had discovered dancer Fredi Washington, and claimed to have invented the Charleston. Her claim is hard to dispute, for she was among the most talented dancers in New York. Her experience with Fredi Washington had led her into choreography, and she had been with the Cotton Club for a number of years, among the first Blacks to break the “whites only” barrier that surrounded the creative aspects of the Cotton Club shows. Elida Webb saw potential in Lena Horne, and she was willing to do everything she could for the daughter of an old friend.

Because of Elida Webb, Lena Horne was able to avoid much of the red tape with which girls auditioning at the club were usually confronted. Still, Lena could not have felt she had much of an edge when she and her mother arrived for the audition.

The tryouts took place during the rehearsal period for the new show, the one that was to follow the “Stormy Weather Show, ” with Cab Calloway’s orchestra and with Aida Ward as the star.

Herman Stark was auditioning some new specialty numbers as well as girls for the chorus. It was morning, and the glamour of the Cotton Club, which Lena had imagined while listening to radio broadcasts from the club, was nowhere to be seen in the dark and cavernous ballroom. The air was heavy with stale cigarette smoke, and one had to grope through a jungle of chairs upended on tables. In the center of the dance floor a work lamp cast eerie shadows over the bodies seated or standing in a semicircle around the arc of the lamp’s spill. Periodically a name was called out and a girl advanced to the center of the spotlight. At a signal the pianist began to play a fast number, and the girl launched into a routine of her swiftest and most intricate steps. Then, “That’s enough!” and the pianist would accompany the girl as she sang a few bars. With that, the audition was over.

Lena Horne’s heart sank as she watched the other auditioners. They seemed so talented, so self-assured. All were older than she, although a girl sitting near her, and with whom she nervously whispered while the other auditions were going on, was just slightly older.

“I could carry a tune, but I could hardly have been called a singer,” Lena Horne later recalled. “I could dance a little, but I could hardly be called a dancer, I was tall and skinny and I had very little going for me except a pretty face and long, long hair that framed it rather nicely. Also, I was young—about sixteen—and despite the sundry vicissitudes of my life, very, very innocent. As it turned out, this was all that was needed.” (4)

When she heard the call “Horne? Lena Horne? She here?” Lena became terrified. She advanced to the tiny lighted spot. She could hear the others’ voices but could not see their faces. She stared into the darkness. The piano began to play, but she couldn’t move. Somehow, above the other voices and the music, she heard her mother’s voice urging her on. She started to whirl, and she spun faster and faster. When the music stopped, she did not. Her wild steps continued until Elida Webb grabbed her arm and forced her to halt. Everyone in the place was roaring with sheer glee.

Lena and Winnie Johnson, the girl who had become her friend while she waited for her audition, were the only two hired that day. She would receive a salary of $25 a week (salesclerks were earning between $5 and $10 weekly; top-notch New York stenographers, $16) to do three shows a night, seven days a week. She had to dodge the truant officer (she was supposed to be attending Girls’ High School in Brooklyn), and she felt very young and naive compared to the worldly older girls in the chorus. Her mother’s friends were horrified that Lena was working in a club run by gangsters, where liquor was sold openly despite Prohibition, and where the chorus girls were rumored to be hired for purposes other than dancing. Lena, however, experienced very few threats to her innocence.

Her very youth protected her. “I was jail bait and no one ever made a pass at me or suggested I go out with one of the customers, which happened all the time to the older girls. The owners apparently figured that any kind of fooling around with underage girls was the quickest way to lose their license.” (5)

Her father and his friends also represented a protective force. Her father was a real “sporting man,” which was one reason why her mother had divorced him. His friends were the gamblers, the numbers people, the men who had the binocular concessions at the track. They were among the few Blacks admitted into the club, although they were always given side booths, near the kitchen. They had known Lena since she was a baby, and they formed a sort of underground protective association.

Then, too, her mother was a conscientious chaperone. She accompanied Lena to the club nearly every night and sat in the dressing room until her daughter was ready to go home. She lectured Lena constantly about being a “good” girl. In fact, she created such a special aura around her daughter that the other girls concluded that Lena thought herself better than they. She was an outsider, prevented by her youth and her mother from being “one of the gang,” and she was very aware of that. Thus, it meant a great deal to her when Cab Calloway remembered her.

A few weeks before Calloway’s band arrived at the Cotton Club, it had been featured at a charity affair at the Para mount in Brooklyn. Some of the Brooklyn Junior Debs, of which Lena was a member, had served as hostesses. On Lena’s first day at the Cotton Club, she was resting on the dance floor during a rehearsal rest period when Calloway strolled by. He caught sight of Lena, hesitated a moment, then called out, “Good Gawd Amighty, there’s Brooklyn!” He walked over to her and introduced her to the musician with him. From then on, he was her hero, and she waited eagerly every day for his “Hiya, Brooklyn!”

The first show Lena was in was not one of the Cotton Club’s big hit shows. Arlen and Koehler did not write the songs for it; they were busy in Hollywood working on the score for Let’s Fall in Love, their first film assignment. Among the songwriters who contributed to the Cotton Club’s twenty-third show were Jimmy Van Heusen and Harold Arlen’s younger brother, Jerry, who collaborated on the song “There’s a House in Harlem for Sale. ”

As usual, a major part of the show was built around the latest dance craze. At that time the craze was the fan dance, which Sally Rand had made famous. The chorus girls carried huge fans, and if they were not quite as naked as Miss Rand was, they were close to it. Lena Horne’s costume consisted of exactly three feathers. “I sensed that the white people in the audience saw nothing but my flesh, and its color, onstage,” she later remarked.

Lena had begun to take singing lessons shortly after coming to the Cotton Club, and her mother reminded the club’s managers at every opportunity that her little girl could sing as well as dance. She enlisted the help of Cab Calloway, and Flournoy Miller, in boosting Lena. Miller had been in on the production of Shuffle Along with Sissie and Blake and had been partly responsible for discovering Florence Mills, Josephine Baker, Gertrude Saunders, and a number of others who had started in Shuffle Along and become stars. He had been hired by the Cotton Club as part of the comedy team of Miller and Mantan, and while the Cotton Club management expected him to be a comedian rather than a producer, they did occasionally ask his advice and they respected his opinions. With Cab Calloway, Flournoy Miller and her mother for cheerleaders, Lena was bound to be given a chance.

One night that chance came. Aida Ward developed a sore throat and had to stay home, and Lena was told to fill in. Calloway gave her a quick rehearsal—she’d heard the number so often she knew the lyrics by heart—and she sang the number in all three shows. The audience was most appreciative, as Stark had expected they would be. Lena’s voice wasn’t anything special, as the older chorus girls did not hesitate to point out to her, but she was young, innocent and beautiful. Her body was not yet fully developed, but it was lithe and graceful, and she had a dazzling smile and immensely expressive eyes and hands.

The next night Aida Ward came back, and that was the end of Lena’s featuredom.

Lena continued to dream, and to study intently the styles of successful singers. After hours in the dressing room she would entertain the other girls with her impressions. One of her best was of Ethel Waters singing “Stormy Weather.” Ethel still appeared at the Cotton Club from time to time, and the story goes that one night in her own dressing room she heard Lena imitating her. She walked into the chorus girls’ dressing room, much to Lena’s embarrassment. “It was just in fun, Miss Waters,” she is supposed to have mumbled.

“In fun, girl?” Ethel cried. “That’s fine singing. You get busy and don’t let anybody stop you from singing from now on.”

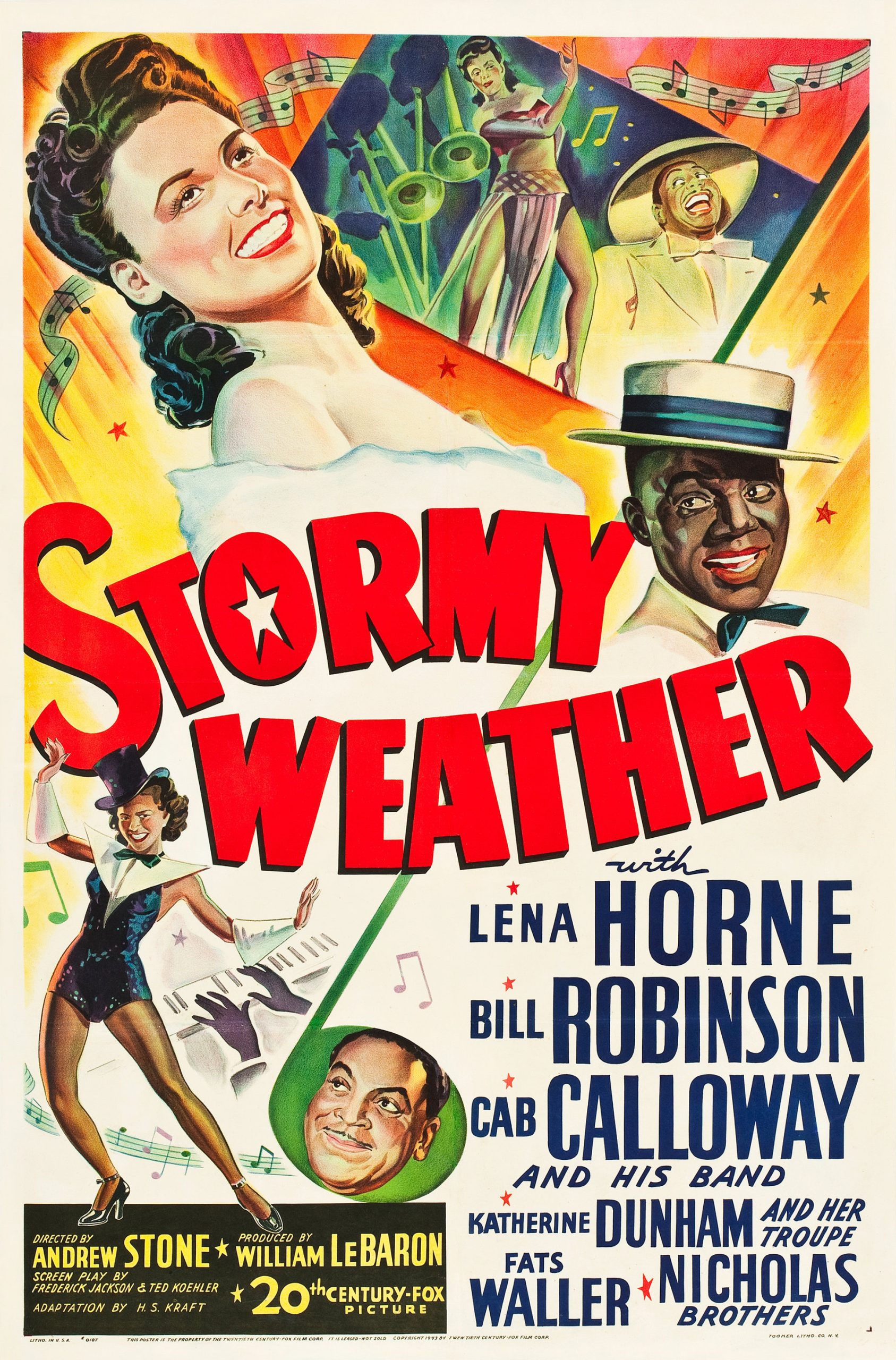

Years later, when the picture Stormy Weather was made, Lena Horne was the star.