6 End of an Era

Prohibition repeal was ratified by the required number of states and became official in December 1933—a Christmas present from America to itself. The Cotton Club was not pleased with the gift. The deepening Depression with its accompanying high prices had cut into the club’s profits, and the end of Prohibition took some of the excitement out of New York night life in general. Ordinarily Stark, DeMange and company could count on the excellence of the shows to keep the crowds coming, but the spring 1934 show was one they could not count on. Of all shows, this had to be the one with a brand-new and untested Cotton Club band. Cab Calloway’s orchestra had left the club at the close of the fall 1933 show and Jimmie Lunceford’s band was hired as a replacement in January 1934. The Cotton Club management was highly dubious about the situation.

The club’s managers were not particularly musically inclined. They knew only what their customers liked.

They liked Duke Ellington’s band with its jungle rhythms. They had liked Cab Calloway’s personality. To the uninitiated, both played “Negro music.” The music of Jimmie Lunceford’s band was a different sound altogether.

After receiving his B.A. in music at Fisk University and doing graduate work at Fisk and New York’s City College, Lunceford had taken a job teaching music at Manassa High School in Memphis, Tennessee. The Lunceford band was organized with students in his class. When they graduated and went to Fisk University, he went with them, taking a job as an assistant professor of music. By the time the students graduated from Fisk, the band was known throughout the South, and Lunceford decided to take them to New York. By that time a few outsiders had joined the band, but the core of the group was Lunceford’s students, and Lunceford was still their teacher, always emphasizing discipline and musicianship.

Lunceford was no showman. In fact, he was a very restrained personality. But he was an exquisite professional, and this quality appealed to the public as much as the showmanship of a Cab Calloway, although at the time it came to the Cotton Club the band was just beginning to acquire a reputation.

Nearly as important to the band as Lunceford himself was the first trumpet player, Sy Oliver. He was the band’s arranger, and he created a highly distinctive sound, a fuller sound with a fuller ensemble than many other arrangers used. Rather than the slow dance tempos or fast, show tempos of other bands, he preferred a medium tempo, with an exciting bounce. Some of the band’s most successful recordings, like “Organ Grinder Swing” and “T’aint What You Do,” were Oliver arrangements.

Arlen and Koehler returned to the club for its spring 1934 show, the first show at the club for Lunceford and his orchestra. Accordingly, perhaps, this show was much more successful than the fall 1933 show, and it ran for some eight months. It starred Adelaide Hall, and one of her feature numbers, “Primitive Prima Donna,” became one of the most popular Cotton Club songs. More famous was the song “Ill Wind,” which she also sang in the show. Intended to be a sequel to “Stormy Weather,” and just as show-stopping, it failed to meet such expectations. Nevertheless, it proved to be one of Arlen and Koehler’s best.

The Cotton Club Boys were introduced in this show. The Cotton Club Girls had become an institution in their own right, and the club’s management, feeling they needed a new gimmick, decided to use a line of young male dancers. Dozens were auditioned, ten were chosen: Howard “Stretch” Johnson, Charles “Chink” Collins, William Smith, Walter Shepherd, Tommy Porter, Maxie Armstrong, Louis Brown, Jimmy Wright, Thomas “Chink” Lee and Eddie Morton. They were made a feature act of the show and their new style of group dancing, in which all moved together in rhythmic unison, was immediately popular. Soon other groups were attempting to imitate their precision style, but no one then could successfully duplicate it. At the end of the eight-month run they had become an established feature of the club. “We knew from the way the folks received us that we were going to be around for a long time,” one of the boys later recalled. Juano Hernandez danced in his exotic, quivering style in an exciting voodoo scene, and there were lively chorus routines in addition to other featured numbers. All in all, the show was a typical, fast-paced Dan Healy production, and with Arlen and Koehler back, it was bound to be a success.

This 1934 Cotton Club Parade proved to be a compendium of gambles, for it was also the first show for dancer Avon Long. Like the Lunceford band, Long was hired by the club’s management despite certain misgivings. Always before, the club’s featured male dancers had been of the “eccentric” type, like Earl “Snakehips” Tucker and Jigsaw Jackson, contortionistic and exhibitionistic. Avon Long’s style, while it had a distinctive jazz beat, was subtle, gliding and smooth. Yet he was strikingly individualistic, and the management had decided to take a chance. Anyway, he had an excellent voice. He was to do the Arlen-Koehler song “As Long As I Live” with a female partner.

The show was Lena Horne’s second at the club, and as the opening drew nearer, she and her mother were resigned to the fact that she would get no break there. The show was cast, and she would be in the chorus, as usual.

Then, at practically the last minute, the girl who was to be Long’s partner quit, and Lena was given her first big break. She became a featured performer at the Cotton Club after less than a year, and like all other featured Cotton Club performers, this meant a great deal of exposure for her. Columnist Louis Sobol reported about an evening in March 1934: “I find that among the folks who were present that evening were Irving and Ellin Berlin, and with them film producer Samuel Goldwyn and his wife; playwright Sam Behrman, Gregory Ratoff, Paul Whiteman and Margaret Livingstone; producer George White; man-about-town Jules Glaenzer; harmonica maestro Borrah Minevitch; Cobina Wright; Marilyn Miller, Lillian Roth, Lee Shubert, Miriam Hopkins, Jo Frisco, Ted Husing and Eddie Duchin.” (1) If just one of these people noticed her, Lena could be on her way to a major career.

Before the show ended its run, Lena had a job on Broadway in a show called Dance with Your Gods, starring Rex Ingraham and Georgette Harvey. Lena’s was a bit part; she played A Quadroon Girl, but it was Broadway nevertheless. Once Lena learned what the producer of the show had been forced to go through in order to get her, she prized the opportunity even more.

The producer, Lawrence Schwab, had to persuade the head of the Broadway mob to intercede with Madden’s people to convince them to agree to Lena’s performing in the show. An arrangement was made whereby she was allowed to skip the first performance at the Cotton Club, but she was expected to rush uptown and work the late shows. All the trouble was practically for nothing. Gods closed after about two weeks, ending Lena Horne’s debut on Broadway.

During her first show at the Cotton Club, Lena had been awestruck by the club, by the wealth of its patrons, by the notoriety of its owners. For the first few weeks of her second show, she was excited about her feature number with Avon Long and bewildered by the rapid pace of her career. But after Gods closed, and she settled into the routine of the spring 1934 show, she began to see the club in a more realistic light. Things she had hardly noticed or thought about before became uncomfortably evident to her. Previously she had been so fascinated by the older chorus girls—listening to their gossip, admiring their sophisticated clothes, envying the frequent male telephone calls they received—that she had failed to notice the conditions in which they worked. Now she began to question why there was only one ladies’ room in the club, and why, given that there was just one, the female performers were discouraged from using it and told that it was for the patrons. She suddenly saw the inadequate backstage facilities and the conditions of the girls’ dressing room:

I saw that twenty-five of us were herded into one tiny, crowded, windowless dressing room in which we had barely space enough to sit before our make-up mirror. I saw that it was littered with loaded ashtrays, coffee containers, newspapers, make-up, fan magazines, the half-eaten sandwiches and cartons of chop suey we were too tired to gulp down, and the bags in which some of the girls brought their knitting or mending. I realized that it reeked of perfume and cigarette smoke, stale perspiration, and the mingled odors of our many meals. And I longed for a breath of fresh air and some place I could stretch my aching limbs and go to sleep. (2)

But she was grateful for the job. She was also aware that if the other club employees—the waiters and busboys and cooks and kitchen helpers and clean-up squad—were not working at the Cotton Club, they probably wouldn’t be working at all. Nevertheless, Lena began to feel exploited. Her $25-a-week salary, which seemed so ample at first, proved to be just barely sufficient to support her family. Times were hard and prices were high, and without the money she brought in each week, she had no idea how they would have managed. Even the truant officer realized this, and while he still visited Mrs. Horne once a week, as was his duty, he took to writing down “missing” in his report on Lena.

Sometimes Lena did not take home $25 a week. Under the contract her mother had signed, and under which all the girls worked, her pay could be docked for lateness, missing a rehearsal, and a long list of minor infractions. The girls received no fringe benefits, such as meals. The club was renowned for its food, especially the Mexican and Chinese dishes and the Southern fried chicken, and although there was a great deal of waste, as there is in most restaurant kitchens, the girls couldn’t even get leftovers. Only under one circumstance were they given a meal at the club, and that was when the entire show was taken upstate to entertain the prisoners at Sing Sing. Lena, who was constantly hungry in those days, remembers those trips with fondness.

Among the performers there was considerable resentment against the Cotton Club management, and Lena began to pay closer attention to the older girls’ gripe sessions, understanding their feelings better now. The chief source of discontent was money. They were sure the club was making a fortune and they felt that their hard work helped bring about this monetary success. They resented having their pay docked for petty reasons and not getting paid extra for the additional performances and benefits they did. But when Lena asked why some of the older girls did not tell the management how they felt, they assured her it would do no good. They would simply be told to “take it or leave it” and that they could easily be replaced. Also, the “boys” were not above using muscle to keep truculent performers in line, and that went for their relatives as well. Lena’s mother and stepfather were impatient for her to have a spot in the shows as a singer. One night after hours her stepfather went to see the club bosses to try to persuade them in a forceful manner—a mistake, as he would soon learn. Some of the bosses’ hoods followed him out into the street and beat him severely.

The general attitude among the Cotton Club veterans was one of resignation and determination to stick it out for the time being and hope something better would come along.

The Cotton Club performers also resented the strict division between white and Black in the creation, production and realization of the shows. Occasionally Duke Ellington did the music for a score, or a Black arranger was called in to do a special number. Clarence Robinson, stage director at the theater in Philadelphia where Ellington’s band had been playing before its first stint at the Cotton Club, was one of the best in his field. Occasionally he was called in to work with the show. But these were exceptions to the rule. In general, whites controlled every creative or lucrative phase of the show, from music score and lyrics, to staging, to choreographing, to costume and set design. The Blacks . . . well, they performed. As Lena Horne put it:

The Cotton Club veterans felt they were blocked and used by white people. They were full of stories about how white people had drawn on their experience, taken their ideas for individual numbers—even for complete shows—and given them nothing in return. Not even a credit line in a program, much less any payment…

They’d talk resentfully about how the town was filled with gifted, creative people. There were lyric writers like Andy Razaf, W. C. Handy, Maceo Pinkard, Eubie Blake. There were dance directors like Leonard Harper, Charlie Davis. And right in the company itself, there was Flournoy Miller, college graduate, who’d been one of the talented four—Miller, Lyles, Sissle & Blake—who’d written, directed, cast, produced, and appeared in that sensation of the twenties—”Shuffle Along.” . . . They had hired him as a comedian in the team of Miller & Mantan, and that was the limit of his actual work. (3)

Lena did not feel the same resentment. She was young and optimistic, and she had not been exposed to many of the more disagreeable aspects of racial or show business politics. She disliked being hungry, and she wanted more money, and she felt the club was unfair in docking her pay for minor infractions, but she did not become bitterly resentful until the night her stepfather and some of his friends were denied entrance to the club.

She would have to quit the club immediately, but her mother realized it would be foolish to leave with no prospect of another job. Angry about the incident, too, she settled for requesting a raise in Lena’s salary. She got $5 more a week. Then she went to Flournoy Miller and asked him to help Lena once again, this time to get her out of the Cotton Club. A short while later an audition for Lena was arranged before Noble Sissle, who was then touring with his highly successful orchestra. She did not have to dance, for obviously she was a good dancer if she was at the Cotton Club. She sang just one song, “Dinner for One, Please James,” and was hired.

Quitting the Cotton Club was not easy. Not only would she leave a hole in the chorus line, but also Avon Long would be without a partner for the “As Long As I Live” number. The attitude of the Cotton Club bosses was that they could fire anyone they wanted, but no one was supposed to quit. On Lena’s last night at the club, both her mother and stepfather confronted the club bosses, who were furious. When verbal persuasion and threats did not work, they beat up her stepfather, pushed his head down a toilet bowl and then threw him out.

Lena and her mother wanted to leave, but one of the boys was sent backstage to make sure Lena did her shows. Thus, while her frightened mother was wringing her hands in the dressing room, a terror-stricken Lena went through the movements of three interminably long shows as if in a nightmare. After the final show ended they left the club under the protection of a crowd of chorus girls, never to see it again. Quite literally, the three Hornes ran away with Noble Sissle’s orchestra.

Lena Horne was not the only one to leave the Cotton Club after the spring 1934 show, although her departure was certainly the most dramatic. Harold Arlen left, too, terminating not only his relationship with the club but also, at least for some years, his successful partnership with Ted Koehler.

During rehearsals Arlen had been offered the chance to do the music for a full-scale revue to be produced by the Shuberts. While he wanted very much to accept the offer, Arlen was deeply troubled about having to leave Koehler and their warm and productive relationship. What worried him most was how to tell his friend. At last, unable to do so verbally, he wrote a note and gave it to Koehler one day at rehearsal. When the rehearsal was over, Koehler read the note, and his reaction was typical in its straightforwardness: Arlen would be a fool not to accept the offer. That night Arlen went out and got drunk.

Arlen would look back on those years at the club with mostly positive feelings. Other than having had to write some songs he considered in bad taste, the only really disagreeable memory was the time when he needed an operation and the Cotton Club heads would not give him the advance on his salary needed to pay for it. Ted Koehler stayed on at the club to do lyrics for a few more shows before moving on. Years later he and Arlen collaborated again.

The Cotton Club still had successful shows after Arlen’s departure. In fact, the very next show, in the spring of 1935, was a considerable success. The Cotton Club Boys, who’d proved so popular in the previous show, were brought back, although seven of the original ten were gone. One, Roy Carter, had died late in 1934, and the others had gone on to various things, not all fruitful. They were a hard-working, fast-living, heavy-drinking group of young men, who spent their money on smart clothes and pretty women, and they were not particularly responsible employees. The newcomers to the group, which consisted of only seven members for the spring 1935 show, were Al Alstock, Ernest Frazier, Freddie Heron and Jules Adger.

The Lunceford band also returned, for the misgivings of the club’s management had proved groundless. The club’s patrons liked his style, and so did a lot of other musicians. By the middle of 1935 the Amsterdam News, Harlem’s weekly newspaper, was commenting: “Lunceford-Lunceford-Lunceford. That’s all you hear in Harlem now.”

The show came to be called the “Truckin’ Show,” after the dance and song of that name, and the title was apt for the times. “Truckin'” meant carrying on despite setbacks. “Keep on truckin'”—it suggested a laborious uphill climb along hard roads, and it symbolized, for many, life itself in the mid-thirties. While almost no one was unaffected, there were certain people and certain areas that seemed to carry more of their share of the burden.

One of those areas was Harlem.

As the Depression deepened, violence in Harlem increased dramatically. Caught in the economic squeeze, the various mobs, which had coexisted in relative peace during Prohibition, began to fight among themselves. The “Mad Dog” situation in 1931-1932 was a tame foretaste compared to what came later. While downtown revelers who came uptown were not targets of the mob violence, quite frequently they became unwillingly involved in it. As reports of injury and death to innocent bystanders caught in the path of stray bullets increased, attendance at the white-oriented Harlem clubs began to decrease.

If anyone was having a hard time “truckin'” in the mid-thirties, it was the residents of Harlem. By 1934, according to the Urban League, 80 percent of them were on relief. They felt trapped. The pride of the early twenties had given way to a new militancy, and a strong anti-white resentment. A young Reverend Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., who would shortly begin to lead boycotts of stores and buses and public utility companies to force hiring of Blacks, identified and verbalized the sources of that resentment in a column in the Amsterdam News. Each week the column “Soap Box” dealt with a particular area in which Blacks were discriminated against or exploited or used. One piece, entitled “Sharecroppers,” addressed itself to the exploitation of Black performers, particularly Black orchestras, by their white managers:

The truth of it is that they are only sharecropping. Duke Ellington is just a musical sharecropper. He has been a drawing account which has been startled to run around $300. per week. At the end of the year when Massa Mills’ cotton has been laid by, Duke is told that he owes them hundreds of thousands of dollars . . . When they finish totaling, there aren’t any profits . . .

Most of these conditions hold forth for the hide-ho master—Mr. Calloway occupying now the highest spot on the Rialto, his men earning under $100 per week. Musical sharecroppers, that’s all . . .

Now take Jimmie Lunceford and his men. They fell into Mills’ snares in the early stages. They, too, were musical peons. Realising this they revolted. Mills had them bound by contract. They owed for their cabin, plot, mule and sorghum. But the boys pulled a fast one—they decided to buy their contracts . . .

Musical sharecropping doesn’t just sing right to this grandpappy’s son. The Negro has sharecropped too long . . . We don’t want anymore paternalism on our job, we want a chance and a fair wage. And we’ll take care of the rest. (4)

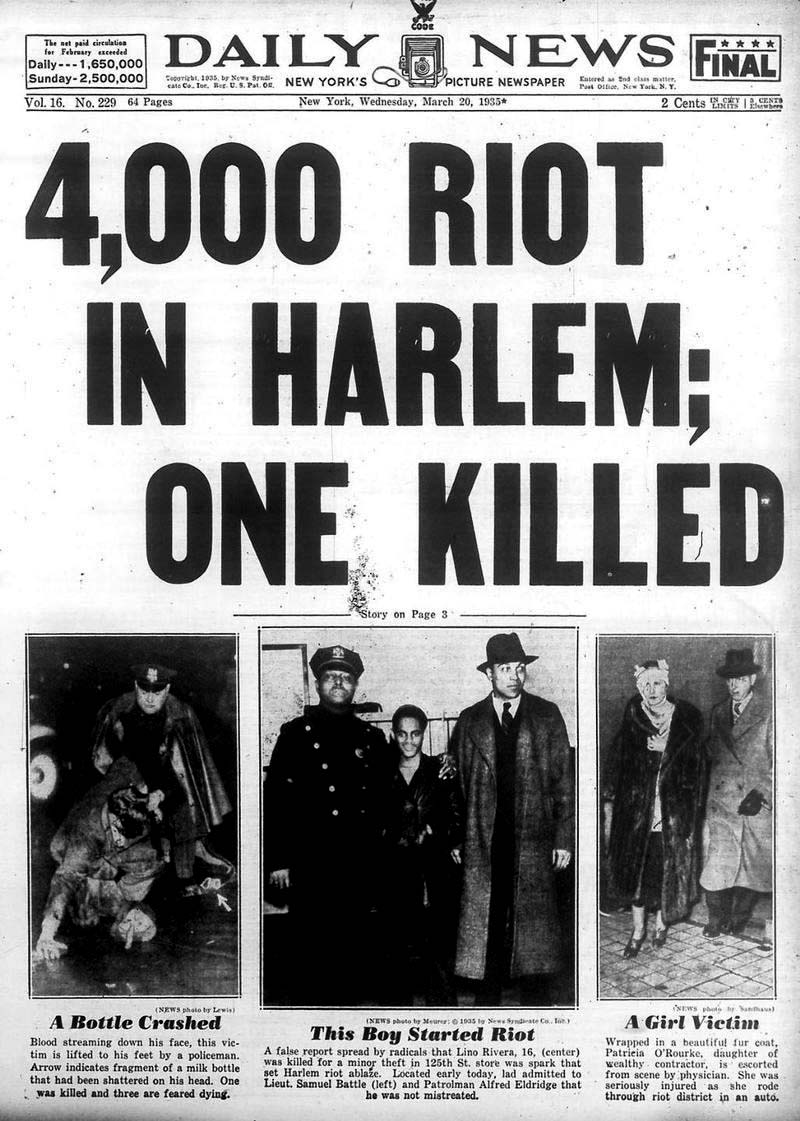

While the working Black musicians had their problems, the average Harlemites, the faceless numbers in Harlem’s unemployment statistics, were the ones who really felt trapped. They could not afford the prices in the white-owned Harlem stores; they could not even get jobs in them. They were hungry; they could not clothe their children; many could not even maintain a roof over their heads. Despair, anger, frustration and resentment boiled up inside them and on March 19, 1935, exploded.

Lino Rivera, a Black Puerto Rican, went to a movie that afternoon. He did not have a job. After the movie, for want of anything else to do, he went to the Kress department store on 125th Street. There the sixteen-year-old spied a ten-cent knife, and having no money to buy it, slipped it into his pocket. He was immediately grabbed by a male employee of the store, and a scuffle ensued. A crowd of shoppers gathered, attracted by the noise. They were Black and clearly on the side of the boy. When Rivera suddenly bit one of his captors on the thumb, the man shouted, ”I’m going to take you down to the basement and beat hell out of you!”

It is hard to establish the exact chain of events that followed. Within moments, the rumor that a white man was beating a Black boy to death spread through the streets of Harlem. And when the people heard an ambulance siren, there was no doubt in their minds that the rumor was true. While the ambulance had actually been summoned for the man with the bitten finger, the people of Harlem were sure that the boy had been brutally beaten. Someone threw a brick and then, like spontaneous combustion, Harlem exploded in a night of looting and burning such as had never been seen before.

The deepening resentment, born of the Depression, and the increased gang violence were casting a pall on the bright visage of Harlem. But there were other reasons for the tarnish on its image. It had been popular because it was new and different. Newness does not last; difference soon becomes commonplace. Black entertainers and musicians who had gained applause and acceptance elsewhere began to look upon Harlem not as “the top” but as the lowly beginning. White socialites were looking for new fads. Harlem was becoming a “has-been.”

The Harlem Renaissance and the era of the New Negro ended as well. Some among the Black intelligentsia had expected it. They had never believed the Harlem Renaissance represented a real and lasting gain in race relations anyway. Wallace Thurman was one. Over the years, his despair over the future of Black Americans and his awareness that the Harlem Renaissance would indeed end had driven him to drink. He died in 1934. Rudolph Fisher was another. He died within a week of Thurman. Langston Hughes was still another. He greeted the end of the Harlem vogue with cynical acceptance. “The depression brought everybody down a peg or two,” he wrote, “And the Negro had but few pegs to fall.” (5)

The reasons for the demise of the Harlem Renaissance were as complex as the reasons for its inception, but the overwhelming factor here, too, was the Depression. It was the Depression that caused the increase in underworld violence and the smoldering anti-white resentment of many Harlemites. The shadow of the sordid world of the slum overcame the artificial light of the myth Harlem. Though liquor was again legally available, the nation itself had sobered greatly; it no longer searched for dreamlands inhabited by people who sang and danced and laughed all day. The Negro passed from fashion.

The Cotton Club management hoped that it was Harlem itself, not the Negro per se, that had fallen from favor. The club had acquired a glamorous reputation over the twelve years of its existence, and its owners were planning to transplant that glamour to a safer, more acceptable location.

The Harlem Cotton Club closed its doors for good on February 16, 1936. It was truly the end of an era.