7 The Cotton Club Comes to Broadway

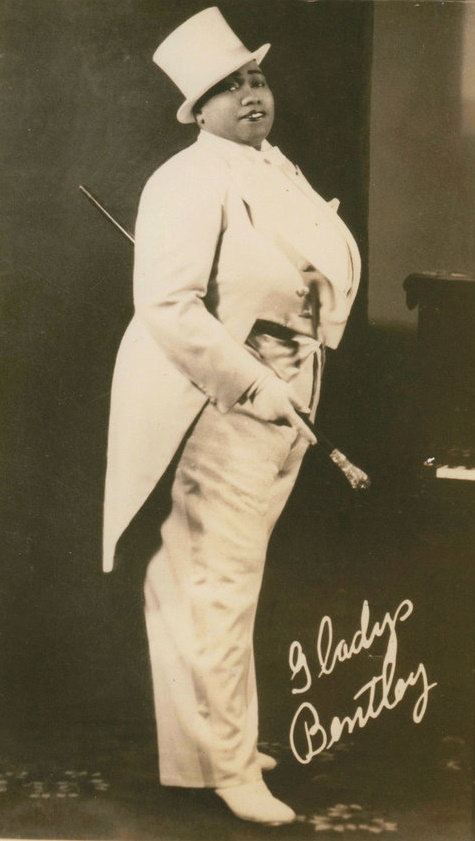

The site chosen for the downtown Cotton Club was ideal. It was a big room on the top floor of a building on Broadway and Forty-eighth Street, where Broadway and Seventh Avenue meet—an important midtown crossroads, and in the heart of the Great White Way, the Broadway theater district. Formerly occupied by the Palais Royal, the site had played host to the downtown Connie’s Inn, renamed the Harlem Club, from 1933 to 1934. However, the Immerman brothers had changed more than the club’s name. Feeling that the time was right, they opted for a club catering specifically to Blacks. They were mistaken, and the club closed within a few months. It was replaced by the Ubangi Club, which offered a “pansy” show in which Gladys Bentley performed in a man’s suit, with a top hat and cane. The Ubangi Club stayed open at that site for about a year, after which it moved farther down Broadway to the cellar that later became Birdland. The move opened the way for the Cotton Club to give the big room musical distinction once again.

The club’s management went to considerable expense to redecorate their new home. Like the uptown club, it was heavily carpeted and terraced, and while a jungle decor similar to that of the uptown club was installed, the old cupid-strewn ceilings and “theater boxes” were retained. Some said the Cotton Club finally had the setting it should have enjoyed all along. After all, its revues had always been much closer to Broadway productions than to night-club shows.

While Herman Stark and the club’s owners were quite certain the club would do well in its new location, they realized a lot depended on a smash-hit opening show, and they lined up the best talent they could find to ensure success. They could not have done better than with Bill “Bojangles” Robinson—and in his fiftieth year as a dancer at that.

Robinson is one of the most loved and respected performers in Black entertainment history. Born in Richmond, Virginia, in May 1878, he began his dancing career at the age of eight, just at the time when Blacks first started to appear in vaudeville. For years, Robinson did one-nighters and fill-in spots in small clubs and vaudeville theaters. In 1903, when he was twenty-five, he teamed up with a partner in the act Cooper and Robinson. When that partnership dissolved five years later, Robinson formed a new act with a man named Butler. After that, he decided to try again as a single performer, and with the help of the agent he chose at that time, Marty Forkins, he did. The two developed a deep friendship and loyalty for each other and continued their relationship until November 1949, when Robinson died.

Robinson got the idea for his stair dance in 1921. As an encore at the Palace, in New York, he danced up and down the stairs on the side of the stage that led down to the orchestra. Audience reaction was so great that he developed and refined the routine until it became his trademark. While not the originator of dancing on steps, his rendition was entirely original.

According to legend, Robinson received his nickname after an all-night poker game in Harlem. Robinson, a big winner in the game, got up and began a happy dance of victory. Des Williams, one of the losers, suddenly exclaimed, “Bojangles! That’s what he is—he’s Bojangles!” He was known by that name from then on.

Robinson rose to stardom on Broadway, in night clubs, and later in movies such as The Little Colonel, In Old Kentucky, The Littlest Rebel and Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm. He staged the dances for the movie Dimples and taught Shirley Temple, among other great stars, dance routines. Meanwhile he achieved another kind of fame—as easily the most generous performer in the business. He played more benefits than any other entertainer. He rarely bothered to ask who or what a benefit was for; if it was a benefit, he figured it was doing somebody some good. In Harlem during the Depression years a benefit performance without him was unheard of. He handed out thousands of Christmas baskets and grocery baskets, often for the Cotton Club. Once he sought to cheer up the poor by personally wrapping some of the packages and handing them out. But when people who received packages not wrapped by Robinson protested, the practice had to be discontinued. In a ceremony complete with speeches by prominent Harlemites, Robinson was named to the honorary office of “Mayor of Harlem.”

Cab Calloway received equal billing for the first downtown Cotton Club show. By 1936 he had become a superstar in his own right. To ensure a crowd-drawing show, it had been arranged that Calloway would revive his “Minnie the Moocher,” and he presented the number every night for the duration of the show.

Top stars were only part of the show’s success. The behind-the-scenes talent was equally important, and Stark and Healy had seen to that as well. Benny Davis and J. Fred Coots wrote the songs. While not an Arlen and Koehler, or a McHugh and Fields, this team was talented and highly successful. Clarence Robinson choreographed the dances, Julian Harrison designed the sets, Billy Weaver and Veronica designed and executed the costumes. Easily the most important acquisition to the staff was Will Vodery for orchestration. Vodery, a quiet, dignified man, had been Florenz Ziegfeld’s arranger from 1911 to 1932. After Ziegfeld’s death in 1932 he had worked for Rudolf Friml, Jerome Kern and Fox Films. He added subtle and imaginative dimensions to the Cotton Club music, and he stayed with the club for a number of years.

The most lavish revue in the Cotton Club’s thirteen-year history opened on Broadway on September 24, 1 936. Robin son and Calloway headed a roster of some 1 30 other performers, among them Avis Andrews, the Berry Brothers, Katherine Perry, Whyte’s Maniacs, the Tramp Band, Anne Lewis, Dynamite Hooker, Wen Talbert’s Choir, the Bahama Dancers, Broadway Jones and the exotic dancer Kaloah. “Black Magic,” “Copper Colored Gal,” “I’m at the Mercy of Love” and “Hi-de-Ho Miracle Man” were among the numbers that were featured.

The Cotton Club Boys had temporarily broken up after the club closed in Harlem. Six of them had continued the act and were booked into New York, Washington, Baltimore and Philadelphia theaters doing their old routines. Like other performers before them, they found that the Cotton Club name opened many doors. When the fall 1936 show premiered at the downtown Cotton Club, however, the Cotton Club Boys were back, and with the Cotton Club Girls they introduced the Susie-Q, which quickly became the latest dance craze.

A bit rough and not quite as fast as it should have been on opening night, the show, like most shows, was refined on succeeding nights, the rough spots smoothed out, the pace quickened. It was, as Variety would have put it, a socko show.

Lured by the show and by the new, more easily accessible location, the crowds flocked to the Cotton Club, which did a turnaway business for the dinner and supper shows. In the third week alone, the club grossed more than $45,000, and in the first sixteen weeks the average weekly gross receipts topped $30,000.

Prices were a little higher at the Cotton Club now than they had been in the early thirties, but then, prices were higher everywhere. The Steak Sandwich, $1.25 before, was now $2.25; Scrambled Eggs, Deerfoot Sausage had risen only a quarter, to $1.50; earlier, lobster and crabmeat cocktails were $1.00 each, now they were $1.50 and $1.25, respectively. Olives, on the other hand, had gone down; a side order, which had once cost 50 cents, now could be had for 40 cents. The most expensive dish on the Chinese portion of the menu, Moo Goo Guy Pan, was still $2.25. Other 1936 prices: Baked Oyster Cotton Club–$ 1.75; Broiled Filet Mignon, French Fried Potatoes–$3; Broiled Live Lobster–$2.50 and up; Egg Foo Young–$1.50. One notable price reduction was the club’s cover charge. Anywhere from $2.50 to $3 in the Harlem days, on Broadway it was $1.50 to $2 table d’hote dinner policy, and no cover charge thereafter. Logically, now that the club had moved away from a neighborhood inhabited by Negro undesirables, it was no longer necessary to maintain a high cover charge to keep them out. Relatively few Blacks crossed the “Mason-Dixon Line” of 110th Street.

All in all, the Broadway Cotton Club was a highly successful blend of old and new. Having learned from the failure of the downtown Connie’s Inn, the Cotton Club people made few changes in their successful uptown formula. The site may have been new, the decor may have been slightly different, but once a patron entered and was comfortably seated, he knew he was in a familiar place. If the former titillating hint of danger associated with the Harlem location was no more, the sense of “rubbing elbows with the mob” was still there. Herman Stark was always around, chomping on a cigar and surveying his domain, and Frenchy DeMange could generally be found at his favorite table receiving visitors or playing cards.

“I used to drop into the Cotton Club after it had shifted activities to West Forty-eighth Street from its former Harlem site,” columnist Louis Sobol later recalled, “and engage in pinochle duels with Big Frenchy DeMange, one of the formidable chieftains of gangdom. They were serious battles, and Frenchy would get apoplectic when he lost, though the stakes were minimal. But once the session was over, he became a good-natured host, and it was difficult to conceive that this big burly man had been on the Public Enemy roster.” (1)

Another major attraction at the Cotton Club that season was the celebration of Bill Robinson’s fiftieth year in show business at midnight, December 12, 1936. Herman Stark had arranged a star-studded and highly sentimental tribute to Robinson, a rather unique one at which, as Ed Sullivan commented in his column the following week, “Broadway laid aside all its cheapness and meanness, and let its hair down to join in . . . ”

Dan Healy and Cab Calloway co-hosted the event. Ethel Merman sang, as did Aunt Jemima. Jim Barton, Block and Sully, and Ted Husing made appearances. Johnson and Dean, famous for originating the cakewalk, danced it again before ringside tables filled with famous faces. Darryl Zanuck had sent a wire from Hollywood, and Shirley Temple an affectionate telegram. Alfred Lunt, Noel Coward, Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia, Fred Astaire, Ray Bolger, Max Schmeling and others made speeches. Through all of it, Robinson beamed with pleasure.

Then Dan Healy began to present the gifts that the Cotton Club kids—members of the chorus, Cotton Club Girls and Boys—had bought for Robinson and his wife. The gift presentation over, he was called to the microphone at 3:45 A.M. Bojangles’ smile faded. As he started to speak, the tears streamed down his cheeks, and he walked off the floor with a handkerchief to his eyes. It was a more eloquent gesture than any speech he could have made.

Despite their careful planning, Stark and the Cotton Club owners were surprised at the great success of their first revue on Broadway. They were just as careful to plan for the spring 1 937 show, and it proved to be an even greater triumph. What made its success particularly gratifying for Blacks in show business was that it was the first show for which all the major numbers were written by Blacks—Ellington, Andy Razaf, John Redmond and Reginald Forsythe.

For Ellington it was a triumphal return. In the ten years since the band had first opened at the Cotton Club uptown it had achieved international acclaim, and had just returned from some film assignments in Hollywood. Ivy Anderson had more than a little to do with the band’s success. She was one of the most exciting female band singers around. She had appeared in Shuffle Along, and in 1931 had been working as the featured singer at the Grand Cafe in Chicago when she was asked to work with Duke at the Oriental Theatre in that city. She remained with the Ellington band for some ten years. She had accompanied the band to England in 1933, along with dancer Bessie Dudley, and had achieved considerable acclaim abroad.

The first record Ivy Anderson made with Ellington was “It Don’t Mean a Thing If It Ain’t Got That Swing,” an Ellington composition. It was the first song to use the term swing for jazz. Swing, in jazz lingo, is a way of playing; there is a lift and a propelling beat that is highly distinguishable to the jazz-familiar ear. The song was an instant hit, and it “made” Ivy Anderson. After that, Ellington and his band continued to rise in fame, but without Ivy Anderson there would definitely have been something missing.

Stark did not rely on the Ellington band alone to draw crowds. He lined up a talent-packed cast of performers to share top billing. In fact, the show was the first, at the Cotton Club or anywhere else, to star so many top Black performers in one production. Ethel Waters was back, having just completed a tour of West Coast night clubs. Back, too, was George Dewey Washington. And the popular young dance team the Nicholas Brothers were making their first appearance at the Cotton Club.

Fayard and Harold Nicholas grew up in the business. Their parents had been the leaders of an orchestra, a forerunner of the name bands that became popular in the late twenties and early thirties. The brothers began their dancing career in 1928, when they were ten and seven, respectively, appearing as an added attraction to a popular vaudeville bill on the stage of the Strand Theatre in Philadelphia, where their parents were playing. By 1937, when they arrived at the Cotton Club, they were already quite successful. In fact, they traveled to New York aboard the Queen Mary after a triumphant engagement in London. But their appearance at the downtown Cotton Club was, as Harold later recalled, “our first real break.” They remained with the club for five years.

The revue’s official title was the Cotton Club Express, and it was the fastest show the club had ever presented. The opening set featured the rear observation platform of a train, and baritone George Dewey Washington, garbed as a train announcer, promised a show that “would corner,” as Ed Sullivan wrote the following day, “the hide-ho and ho-de-ho market.”

Harold Nicholas of the Nicholas Brothers did some fast-paced hoofing to “Tap Is Tops,” which gave way to Kaloah’s wriggling to Ellington’s “Black and Tan Fantasy.” Anise and Aland executed a graceful waltz number, followed by a dance specialty by a new group, the Three Giants of Rhythm. Then Ethel Waters, supported by a background of beautifully gowned chorus girls, sang what was planned as the major song of the show, “Where Is the Sun?” written by John Redmond and Lee David.

The revue was packed with dance numbers. The Nicholas Brothers did a specialty number, followed by the Cotton Club’s bow to the growing South American influence in U.S. dancing. It was an ambitious production number called “Chile,” sung by Ivy Anderson, and danced not only by Anise and Aland but also by Renee and Estela, a rhumba team whom Stark had gotten from the Club Yumuri especially for the number. Bessie Dudley shook her hips to Ellington’s “Rockin’ in Rhythm,” and Bill Bailey tapped out “Tap Mathemetician.”

Then the tempo shifted. Ethel Waters came onstage to do some of the songs that she had made, and that had made her, famous—”Stormy Weather,” “Happiness Is Just a Thing Called Joe.” It was in this performance, less formal than the lavish “Where Is the Sun?” production, that she was at her best. As one columnist put it: ” . . . when you encounter her striking interpretations of some songs ranging from her classic ‘Stormy Weather’ to Cole Porter’s sardonic ‘Miss Otis Regrets,’ you will see that she is, among other things, a truly creative player. She dominates the performance, dominates it with her unflagging spirit, her casual splendor and her instinctive theatrical wisdom, and I suspect that, even without the other virtues of the evening, she, splendidly accompanied by her brother on the piano and her husband on a muted cornet, would revive for you all the glories of a fine tradition.” (2) (The columnist was either misinformed or just being polite in calling the trumpet player, Eddie Mallory, Ethel’s husband. Her half-brother, Johnny, played piano with Mallory’s band for a while.)

As a finale Mae Diggs, the Nicholas Brothers and the chorus, dressed in chicken costumes, introduced “peckin’,” billed as the new dance craze to succeed the SusieQ. At first the tune, “Peckin’,” was properly credited to Ellington, for it came straight out of Cootie Williams’ solo in “Rockin’ in Rhythm.” The show was a smash—lively, fast-paced and, to quote Ed Sullivan once again, “easily the most elegant colored show Broadway has ever applauded.”

Among the first-night customers were Sylvia Sidney, Lou Holtz, and physician Dr. Leo Michel, known among theatrical people as Dr. Broadway, and they were among the lucky. From the very first night the club was turning away crowds, and by the fourth week the show had played to over 50,000 persons, breaking all previous club records. Anticipating receipts that would come close to the million-dollar mark, Herman Stark quickly moved to extend the show’s run and to make sure its stars would remain with it until it closed. In mid-April the happy announcement came—both Ellington and Ethel Waters had agreed to postpone previous commitments to assure continuance of the lavish revue until June 15.

One night Leopold Stokowski came in and sat, alone, in one of the boxes. Ellington noticed the white-haired conductor and walked over and introduced himself.

Stokowski rose to meet him. “I have always wanted to meet you and hear you conduct your compositions,” he said.

“This is one of the proudest moments of my life. I’ve always had the greatest admiration for you,” Ellington said.

“Tell me,” Stokowski continued, “what are you striving for in your music?”

“I am endeavoring to establish unadulterated Negro melody portraying the American Negro,” Duke explained. And then he proceeded to illustrate, leading the band through a medley of his concertos.

Stokowski applauded loudly. “Mr. Ellington,” he said, “now I truly understand the Negro soul.” (3)

The conductor then invited Ellington to his concert at Carnegie Hall the following evening, and Duke had the honor of sitting alone in a box at Carnegie, while, as columnist Louis Sobol put it, “the Caucasian conductor led his vast orchestra [the Philadelphia] in an interpretation of the vague white-folks’ soul.”

Sobol’s comment indicates that for some, at least, the idea that the Negro soul was somehow purer and truer than the white persisted. But these some were now fast approaching a minority. So, too, were those whites who opted for the complex rhythms of Negro jazz as opposed to the sounds of swing. In 1936 the “swing era” had begun in America, with large white bands like that of Benny Goodman bringing jazz to a much wider public. The same columnist quoted earlier who praised Ethel Waters in the show also praised Ellington, but appended the following: “I trust that you approve of him [Ellington] and his orchestra—just as I trust, incidentally, that you are an enthusiast for Benny Goodman and his associates.” It was a movement that Ellington, for one, cared little for. He took to making a strong distinction between his work and that of the so-called swing bands.