9 The Last Years

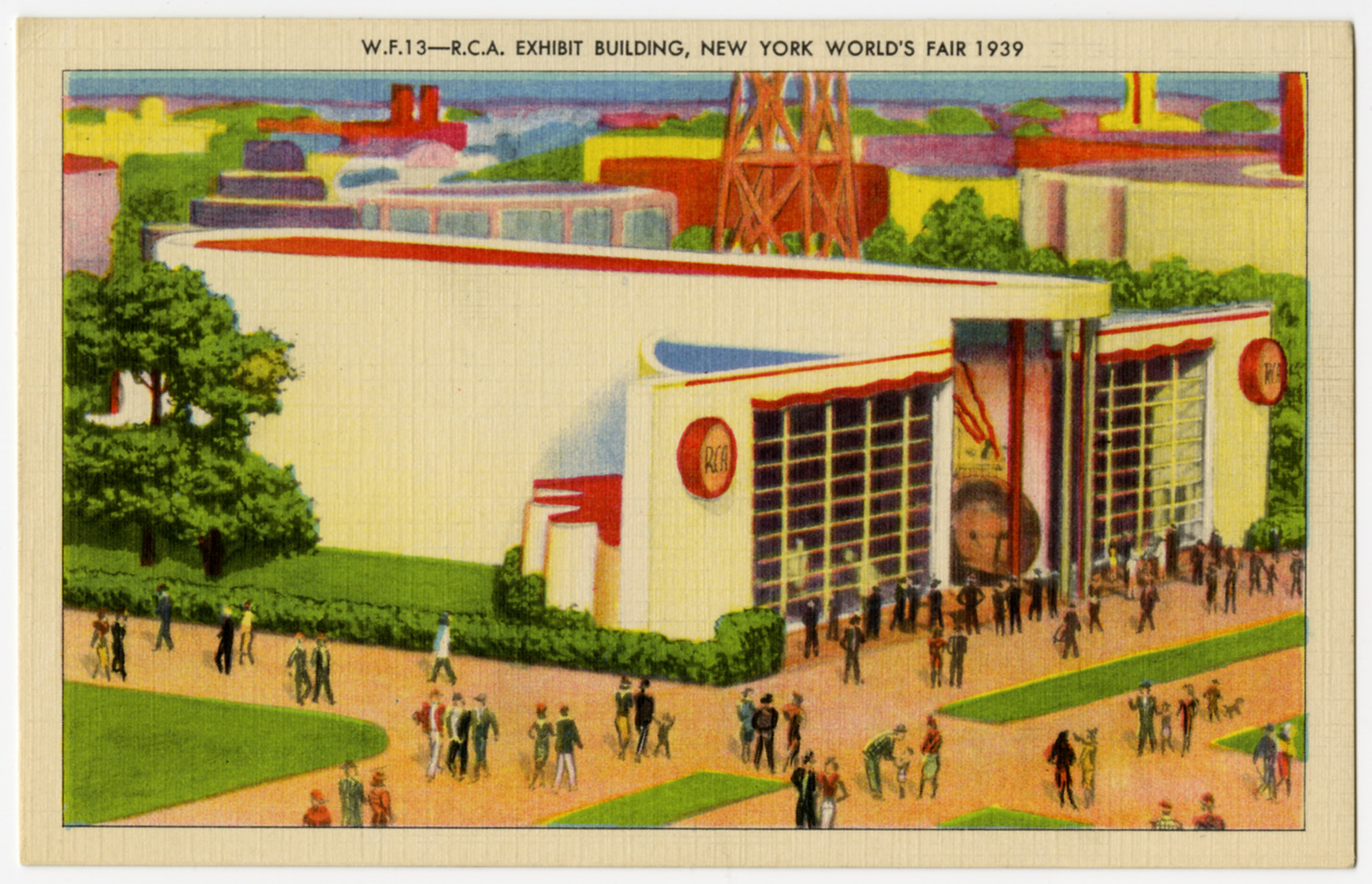

In 1939 the World’s Fair came to New York for the first time since the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations in the Crystal Palace in 1853–1854. Since then there had been world’s fairs in other cities, like Chicago and Philadelphia, but New York had viewed the entire world’s-fair concept with serene indifference. The city had neither the time nor the space for such gaudy nonsense. What happened to change the city’s attitude is hard to determine. Perhaps the Depression had something to do with it, or perhaps it was the success of Chicago’s Century of Progress in 1934 that jostled New York out of its lofty complacency. Whatever the reason, the city threw itself into preparations for the biggest world’s fair ever. Its theme: Building the World of Tomorrow. Eighteen nations were represented when the fair opened on April 30, 1939.

The fair became the focal point of slick advertising campaigns, the gimmick for new products and for old products looking for a new image. There was still the sense of wonder that a “world’s fair” was feasible, that modern technological advances and modern travel could make possible a cooperative exposition among a group of countries separated by thousands of miles. For New Yorkers, in addition, it was a chance to celebrate their city. For other Americans, it was a reason to travel to the Big Apple, to see the things they had always heard about. Throughout the country, the World’s Fair engendered considerably more excitement than any subsequent exposition.

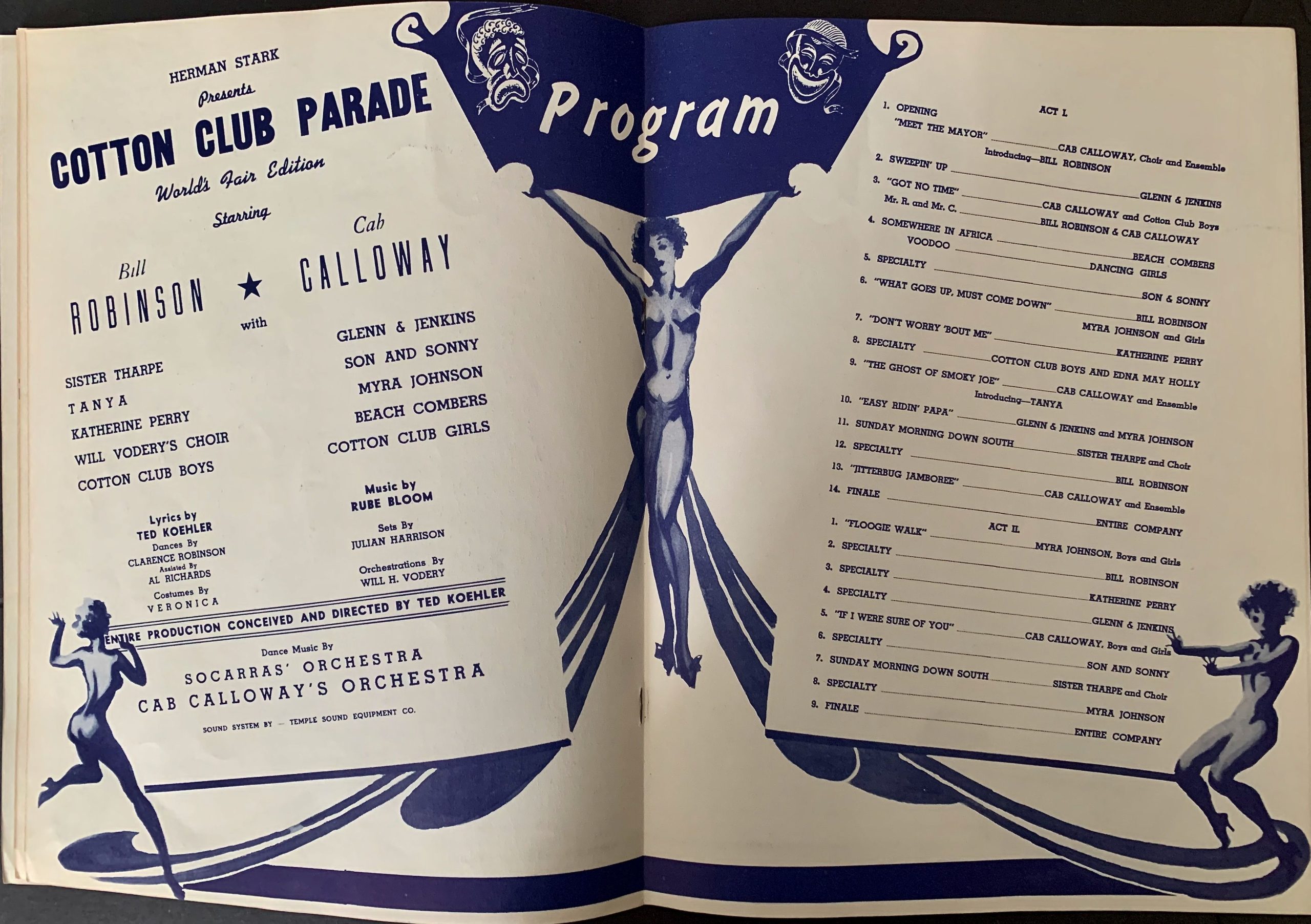

Naturally, the show that opened at the Cotton Club at midnight on Friday, March 24, 1939, was billed as the World’s Fair Edition of the Cotton Club Parade, although there was nothing in the show that was particularly related to the events out in Flushing Meadows, Queens. The club had been spruced up for the World’s Fair season. The stage had been enlarged, and the orchestra area had been lowered from the dance-floor level, giving both stage and floor a more theatrical setting. The show was as talent-packed as Herman Stark could manage.

Duke Ellington’s orchestra would have been a natural for the Cotton Club’s World’s Fair Edition. After all, Ellington had contributed to the club’s international renown, and vice versa. But Ellington was unavailable, having been booked into a tour abroad to begin in March. Even if he had been available, Ellington would probably not have cared to book into the Cotton Club. Such a stint demanded a bit more dazzle than Ellington could likely have mustered at the time. He was going through some serious changes that spring, both in his professional and in his personal life.

Professionally, he had taken the great step of leaving Irving Mills. For years, outsiders had criticized Mills’s relationship with his clients, charging, as Adam Clayton Powell had put it, that he made his clients “musical sharecroppers.” Ellington had always brushed these criticisms aside, explaining that he was grateful to Mills for early financial support and wise business counsel. By late 1938–early 1939, however, Ellington had begun to feel that he wasn’t getting the attention he deserved from Mills, who managed Calloway as well as close to a dozen other groups, large and small. Ellington was disgruntled, but he might not have broken with Mills if he had not decided one afternoon to go to Mills’s office to look at his books. Biographer Barry Ulanov reported:

Duke sat down at the table and looked through all the books of Duke Ellington, Incorporated, the record of his business association with Irving Mills. He looked at almost every page, at some with greater interest than others, at the reports on his best-selling records and those which hadn’t sold so well, at the results of this theater booking and that location stand, the Cotton Clubs, East and West. Europe and short stands from coast to American coast.

“Thank you very much,” Duke said to the secretary, after better than an hour’s poring over the books of Duke Ellington Inc. He got up slowly, adjusted his jacket and tie, put on his hat and overcoat and walked out of the office. He never returned. In the spring of 1939, Duke signed a contract with William Morris, the oldest and greatest of the vaudeville and radio booking agencies, at that time making a belated entrance into the band business. (1)

A break in Ellington’s personal life also occurred in 1939. For the past couple of years there had been many strains on Duke, and he and Mildred were not talking things over as they once had. While they still loved each other, they had lost something they could not regain, or that Duke, at least, did not want to make the effort to regain. During one of his earlier bookings at the Cotton Club, Duke had met chorus girl Bea Ellis, who made no attempt to hide the fact that she was crazy about him. Initially Duke was merely flattered by the attention. As the months went by, however, and they spent time together at the club and elsewhere, he began to respond to Bea’s affections. In late 1938 Mildred, who had heard about Bea, asked Duke if he loved the beautiful showgirl, and he answered that he thought he did. That was enough for Mildred. Early in 1939 the two were divorced, and Bea Ellis subsequently became the new Mrs. Ellington. Mildred, who eleven years before had herself been a beautiful young Cotton Club chorus girl with her whole career ahead of her, returned to Boston.

Bill Robinson and Cab Calloway shared Wop billing for the spring 1939 Cotton Club show, although it was clear that Robinson was the major attraction. He certainly deserved it. At age sixty he was starring simultaneously in the Cotton Club show and in Michael Todd’s The Hot Mikado, staged by Hassard Short.

During the two weeks prior to the opening of the show the Cotton Club was closed, to permit all-night rehearsals. The club was in a frenzy of activity, and the performers were often exhausted and irritable. Not Bill Robinson. Shuttling back and forth between Hot Mikado and Cotton Club rehearsals, he put in a daily sixteen hours, first at the Broadhurst Theatre, on West Forty-fourth Street, and then at the club. At two o’clock in the morning he was bubbling with energy and humor, instructing the chorus line in the intricacies of his soft-shoe routines. A quick study, he memorized his scripts in minutes, then turned to help the others with theirs. He did not have to be so energetic at the Cotton Club rehearsals. There was no question that the Hot Mikado show took priority. In fact, out of deference to Mike Todd and the opening of Mikado, Herman Stark postponed the opening of his show four days.

It proved to be a clever decision. The Hot Mikado was received with rave reviews. The New York Daily News gave it a XXX½ X rating and the Telegram called it “Magnificent—loudest, craziest, hottest and most brilliantly organized jam session of this cock-eyed jazz age.” It did not hurt the Cotton Club’s business at all to have as the star of the show the star of a smash Broadway musical.

Relieved from the pressure of sixteen-hours-a-day rehearsals, Robinson now put in an eight-hour performing day. After the 7:30 P.M. show at the Cotton Club he dashed to the Broadhurst for the 8:40 show, then back to the Cotton Club for the midnight and 2 A.M. shows. And on Wednesdays and Saturdays there were additional afternoon matinees of The Hot Mikado.

Robinson’s act at the Cotton Club did not suffer at all as a result of his Mikado performances. He was a true showman and a real professional and the audience recognized this. Grinning from ear and ear, strutting across the floor with his shoulders thrown back, his derby tilted rakishly on his head, his feet tapping rhythmically with effortless grace, he received rave reviews at the Cotton Club as well.

Still, Cab Calloway managed to hold his own. His energetic performance, while not as awe-inspiring as that of the sixty-year-old Robinson, was a definite crowdpleaser. Leading chorus and dance numbers, swapping wisecracks with Robinson, and shouting “The Ghost of Smokey Joe,” a production number in his “Minnie the Moocher” series, Calloway received his own share of mentions in the Broadway columns.

Robinson and Calloway headed a fine, talented cast. Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Stark’s “find” of the previous season, lead the choir in spirituals, among which “Sunday Morning in Harlem” was considered by some the highlight of the show. She was so well received that two weeks after the show opened, revisions were made to give her more exposure. She was allowed to leave the stage back of the orchestra pit and to come down to the floor and share the spotlight with Robinson in a special number. It brought down the house.

Other performers included dancer Tanya; Katherine Perry; Glenn and Jenkins, who with Myra Johnson did a risque ballad; dancers Son and Sonny, whom Stark had discovered at the Grand Terrace Cafe in Chicago, where he had gone with Jimmie Braddock after the Louis-Braddock fight; the Beachcombers; the Six Cotton Club Boys; and Will Vodery’s Choir. It was the first time that Vodery, who had been choir director and arranger at the club for a year, was given such billing.

Benny Davis and J. Fred Coots had left the club after writing the score for the fall 1938 show, and Ted Koehler had returned to do the songs with composer Rube Bloom. While their songs did not prove as memorable as those of some other shows, “Don’t Worry ‘ Bout Me,” “Got No Time” and “If I Were Sure of You” became respectable hits; and their “What Goes Up Must Come Down” is as familiar today as it was in 1939.

With Clarence Robinson’s choreography, Frances Feist’s costumes and Julian Harrison’s sets, the World’s Fair Edition of the Cotton Club Parade was in the best Cotton Club tradition, and it attracted record-breaking crowds. Among those visitors during the first four nights after the show opened: J. Edgar Hoover, Clyde Tolson, night-club comedian and musical-comedy performer Eddie Garr, Mary Martin, Winthrop Rockefeller, Charlie Barnet, Hassard Short, Billy Rose, and Leo Spitz and Nate Blumber, production manager and president of Universal Pictures, respectively. During the first two weeks of the show’s run the club grossed $67,000, Herman Stark reported, and an estimated 7,000 persons were turned away during the first week alone.

There was no question that the presence of the World’s Fair was good for business. Visitors to the fair made it a point to visit the Cotton Club as well. To increase its attraction the club inaugurated a special series of Sunday theatrical nights, after the midnight show, to honor such stars as Jimmy Durante, Alice Faye, band leader and composer Abe Lyman, Tommy Dorsey and Sammy Kaye.

Business was so good that the Cotton Club management decided to keep the club open through the entire summer, for only the second time in its sixteen-year history. The show that played for the summer was not as ambitious as the busy-season shows, and Stark had cut down the running time of the show to one hour, although he continued his policy of presenting three shows nightly. There were few big-name acts. The comedy team of Buck and Bubbles were billed as the stars. June Richmond, Tip, Tap & Toe, Aland and Anise, Floyd Smith, Vic Terell, Tommy Wilson and Edna Mae Holley contributed their talents.

One notable addition to the roster was Andy Kirk’s orchestra, which had been hired to replace Cab Calloway’s band. Kirk and his group were out of Kansas City and had been playing in New York for six years, mostly in Harlen night clubs, before being booked into the Cotton Club. While not particularly well-known to the public at large, the distinctive and original style of the Kirk band had already attracted a considerable following among record fans and members of other bands. Its guitarist, Floyd Smith, was largely responsible for the vogue of electric-guitar players in swing bands. It was his playing that had caused Benny Goodman to look for an electric guitarist back in 1938, leading to the discovery of Charlie Christian and the formation of the Goodman sextet.

The Kirk orchestra was distinctive, too, in that its one female member, a slim young girl named Mary Lou Williams, was not its vocalist but its pianist. Not only did she play the piano; she was also a composer and arranger. It was she who, having heard of the playing of swing pianist Roll ‘Em Pete Johnson, composed the driving tune “Roll ‘Em,” which was popular with all swing bands of the day. Both this piece and her composition “Camel Walk” had been featured earlier that year in Goodman’s concert with Leopold Stokowski at the Hollywood Bowl. The Kirk orchestra proved an excellent choice for the Cotton Club’s summer 1939 run.

Ted Koehler and Rube Bloom were unavailable to write a score for the new summer show, so Sammy Cahn and Saul Chaplin were hired to write it. Their work for the show was not particularly memorable, but it did give Sister Rosetta Thorpe’s career a boost. With the opportunity to display her talents in greater degree now that she was not billed among so awesome an array of performers, she proved a major highlight of the show. Her best song, written for her by Cahn and Chaplin, was “Religion on a Mule,” for which she sat astride a live mule led out onto the stage. Sung as only Sister Tharpe could sing it, the song had all the spirit and rhythm of an old-fashioned Southern religious revival meeting.

The Cotton Club’s summer 1939 show had hardly gotten off the ground than Herman Stark found himself wishing for a little help from above, or at least wishing he had kept his mouth shut when reporters asked him about the club’s profits. On July 14, federal indictments for income-tax evasion were handed down against the Cotton Club and five other New York night clubs.

The government had launched a concerted campaign to enforce collection of taxes from night clubs and other amusement enterprises, and had decided that the most successful way to accomplish its goal was to press criminal charges, seeking prison sentences as well as fines.

The indictment naming the Cotton Club Management Corporation also accused Herman Stark, President; George Goodrich, Accountant; and Noah L. Braunstein, Secretary-Treasurer, on four counts of failure to pay, and embezzlement of taxes. Conviction could bring prison terms up to twenty years and $20,000 in fines. Other clubs indicted were Choteau Moderne, El Toreador, Man About Town Club, Little Rumanian Ron Dez Vous, and a Brooklyn club, the Royal Frolics, Jamaica.

Naturally, the Cotton Club Management Corporation pleaded not guilty to the charges, as did the other groups and individuals indicted. But the government meant business, and eventually all paid fines. Stark had tried to head off the indictment by paying $500 on account early in the week of July 10, with a promise to pay the remainder of the $2,900 the club owed on Monday, July 17. But the indictments were handed down on Friday the 14th, leaving Stark with no choice but to go to court. Later, when the case came to trial in the fall, the Cotton Club was slapped with a hefty fine. Stark was in a bad mood that autumn.

For the first time the downtown Cotton Club was feeling the effects of the Depression. Rent at the choice Broadway site was high. So were labor costs. A club employing as many performers as the Cotton Club had a huge weekly payroll. Then, there was a stronger musicians’ union with which to contend. One of its requirements was one day off per week for its members. During the summer Stark had refused to shell out the money for a fill-in crew for the one night, but once fall arrived, he had to do so. These expenses, combined with the tight federal watch on the club’s accounts, which allowed for no further embezzlement or cover-up, made the club a luxury its management was fast becoming ill able to afford. An outsider would have been unable to discern the Cotton Club’s money troubles. Prices did not rise, service did not decline, and the fall entertainment was as lavish as ever. In fact, the club presented two separate shows that fall.

The first show took advantage of the fact that Bill Robinson would be in town until The Hot Mikado went on tour in early November. It was a semi-vaudeville variety show, and the band hired, both for it and the major show to follow, was Louis Armstrong’s.

This was the first time Armstrong had ever played at the club, and the event was a long time in coming. He had played at just about every other major New York club featuring Black entertainers, and his recordings were on juke boxes across the country. His style was not the polished Duke Ellington kind. It was not Kansas City, like Andy Kirk’s, but New Orleans. Armstrong was famed for his “scat singing” of pure nonsense syllables, a style not unknown to a club that had so often featured Cab Calloway, so that was not the reason for his belated appearance at the club. Perhaps the chief reason was that the club may have considered him “a little too Negro.” He was criticized in some circles for, as one columnist put it, “his ape-man antics.” He was also very dark-skinned, much darker than Calloway or Ellington, and the club’s policy had always been to feature Negro entertainers, but . . .

The early-fall variety show was called a “warm-up” for Armstrong. It may also have been a trial period for Armstrong. The show was highly successful. Robinson and Armstrong were supported by the Zephyrs, Avis Andrews, Princess Orelia and Chilton & Thomas. There were no lavish sets, no high-stepping chorus lines, and Dan Healy was not even emcee; Bobby Evans filled in for him in that capacity. Still, it was a good show. As one columnist put it:

To be sure there aren’t a floor full of dusky chorines doing the 1, 2, 3, nor costumes, nor big production numbers. But somehow we didn’t miss them at all the other night. Girls just get in the way when the Mayor of Harlem starts strutting down the floor . . . Although such a magnificent presence just naturally needs elbow room, he does leave a little space for Louis Armstrong, whom Mr. Robinson terms the “one-man Yankee team,” . . . his trumpet tooting is phenomenal. (2)

When the show closed and rehearsals began for the major show, Louis was in solid with the Cotton Club management. And before the year was out he would be in just as solid with a beautiful chorus girl named Lucille Wilson, who back in 1932 had broken the chorus-line color bar at the Cotton Club. Louis Armstrong and Lucille Wilson got married, and their marriage lasted until Armstrong’s death.

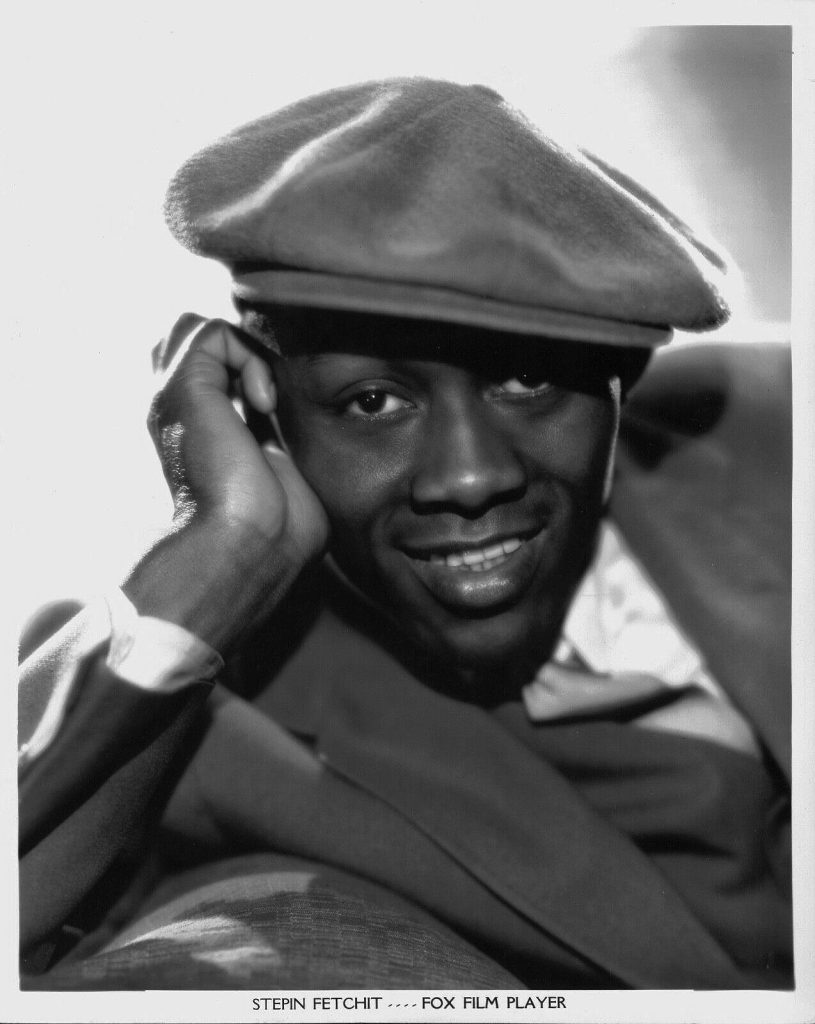

None other than the professional lazy man, Stepin Fetchit, replaced Robinson as Louis Armstrong’s co-star for the big show, and if Robinson had required special arrangements at times, they were nothing compared to what Stepin Fetchit expected, and Stepin Fetchit usually got what he wanted.

He was born Lincoln Theodore Perry in Key West, Florida, son of a cigar maker. Like so many other Black entertainers of the era, he started in show business early, getting into minstrel shows in 1915 at the age of thirteen. He traveled around with one show or another for ten years before reaching Hollywood in 1925, and after that he had steady work in films. Legend has it that he got his name originally from a race horse called Fetch It. The name intrigued him, and he wrote a comic song, “The Steppin’ Fetch It,” whose title, over the years, became his name.

Starting with small parts in such movies as In Old Kentucky (1927), The Ghost Talks (1929) and Show Boat (1929), his caricature of a lazy, no-account good-for-nothing was so successful that he became the first Black actor actually to be under contract to a major studio. From 1929 to 1935 he appeared in twenty-six films, several of them with Will Rogers, often working in as many as four at a time. He made a great deal of money, and spent it lavishly. And the more Twentieth Century-Fox exploited his spending in order to promote its young Black star, the more lavishly he spent. Stories circulated about his high living. He had six houses, sixteen Chinese servants, imported $2,000 cashmere suits from India, threw huge parties, and had twelve cars, one a champagne-pink Cadillac with his name in neon lights on the side. He was a star, and at the Cotton Club he expected to be treated in the style to which he was accustomed. Before arriving at the club, he informed Stark of his requirements, typing the letter himself.

Mr. Herman Starks:

This is to advise you that it will necessitate you to furnish me with a Chinese girl singer and a very light straight man for support of my original song presentation during my engagements at the Cotton Club.

Also you are to furnish the following props and costumes: a white French phone with a fifty-foot cord and a proper plug-in connection, and battery telephone bell to ring continually offstage; also, a minstrel covered chair, and tambourine; a small piano and stool; a green low-back over-stuffed parlor chair; a collapsible service tray and tea wagon; two school desks; a prop pinto horse.

Also three microphones—a long, short and table microphone, all connected for use; three school girl costumes for the Dandridge Sisters and a school teacher’s outfit for principal to be selected; a minstrel outfit for me, and an interlocutor’s outfit for principal to be selected; a Philip Morris uniform and maid’s outfit for the Chinese girl.

Also, a French artists’ beret and jacket for me; and two new song arrangements each week, the music and word material I will furnish and their arrangements furnished by you; also a Will Rogers outfit and makeup for straight man.

During my engagement I can be the only one allowed to talk other than the straight man and all other acts must have fast moving routines and songs. You must furnish a new Cotton Club book to include printed matter I have in collection with these song presentations and my picture must be painted among the Cotton Club stars on the upstairs bar lobby wall in place desired by me.

Nota bene. These props, costumes, printing matter, art work and arrangements with all principals is absolutely necessary, with rehearsals at least three days before my opening. So let’s get going if I am to open as we desire Wednesday night.

Regards,

Stepin Fetchit (3)

While there exists no record of Stark’s response to Stepin Fetchit’s letter, clearly there were some negotiations, and some compromise on Fetchit’s part. When he opened at the Cotton Club he did not, for example, have “a Chinese girl singer.”

The major fall show at the Cotton Club opened on November 1 at midnight. Fetchit and Armstrong presided over some fifty other performers, fewer than in most previous major shows at the club and indicating some financial belt-tightening on Stark’s part. All of the lesser acts from the earlier variety show were retained and were joined, perhaps most important in the minds of many of the audience, by the Cotton Club Girls, although the line, numbering sixteen, was smaller than that of previous shows. Other additions included singer Maxine Sullivan, comedians Stump and Stumpy, singer Midge Williams, dancer Princess Vanessa, Soccares’ orchestra for dancing, Dan Healy to share emcee duties with Bobbie Evans, and the Tramp Band. They were all talented performers, and the behind-the-scenes talent was equally competent. All were Cotton Club veterans: songwriters Saul Chaplin and Sam Cahn, costumers Frances Feist and Veronica, director Clarence Robinson. Yet the show lacked something. It did not have the excitement or, Stepin Fetchit’s instructions notwithstanding, the fast pace of earlier shows. One columnist wrote: “It’s a slowerupper.” Something had gone out of the Cotton Club shows, and primarily it seemed to be spirit. Undoubtedly the entertainers in and the creators of the show were aware of Stark’s money worries.

The Cotton Club closed its doors good on June 10, 1940. Of course there was much discussion about its closing, for it had been one of the most talked-about night clubs in New York for a quarter of a century. The chief reason seemed to be, as one columnist put it, “lack of the famous old filthy, nasty, lucre”; but there were other, contributing factors. Tastes in entertainment had changed. Lavish Ziegfeldtype shows were no longer as popular even on Broadway, and it followed that they could not last long in night clubs. Tastes in jazz had changed as well. Beginning in 1936, with the advent of large white bands like Benny Goodman’s, a much larger public had become responsive to jazz, and to the “swing” style of these bands. The more exposure Goodman’s or Artie Shaw’s or Tommy Dorsey’s bands received, the more accustomed the public became to their version of swing. Particularly the younger generation of Americans considered Ellington’s style, for example, less exciting, too complex, too subtle. Ironically—or perhaps naturally, given America’s racial traditions—the Duke was upstaged in commercial popularity by the “King of swing,” Benny Goodman.

When the Cotton Club closed, Andy Kirk’s band was being featured. Its recording of “Until the Real Thing Comes Along” was selling quite successfully at the time, but the band and the former winning Cotton Club show formula just could not bring in enough customers to maintain the club as a financially profitable enterprise. Ironically, the club, founded on the ground swell of Prohibition, having weathered the Depression, floundered in the tides of changing public taste. The Cotton Club closed because it was an idea whose time had gone.