Chapter 2: Cross-Cultural Measurement of Cyberbullying

Krista Mehari and Natasha Basu

ABSTRACT

The field of cyberbullying research lacks a comprehensive understanding of its prevalence across the world. Its culturally-specific and universal predictors and outcomes, as well as effective methods to prevent or reduce its perpetration across the globe, are poorly understood.

This chapter covers the following:

- Current issues in cross-cultural measurement of cyberbullying

- Use of different terms to describe the phenomenon, and different definitions

- Difficulties that arise from using a single-item, definition-based measure (i.e., surveys that define cyberbullying and then ask youth how frequently they cyberbully)

- Existing measures of cyberbullying in Asia, and gaps in measurement

To address the issue of cyberbullying, it is critical to develop culturally relevant measures using rigorous measurement development and testing strategies.

A solid understanding of how best to measure cyberbullying within cultural contexts is vital for conducting cyberbullying research. Accurate cyberbullying measurement will make it possible to identify outcomes associated with cyberbullying and explore malleable risks and protective factors. Conducting longitudinal research on cyberbullying outcomes, while controlling for other co-occurring adverse experiences (such as in-person victimization) is needed. This approach is key to identifying the need for public health cyberbullying prevention research. Research on malleable risk and protective factors on cyberbullying will inform the development of effective cyberbullying prevention strategies. For all the stages of cyberbullying research, accurate cyberbullying measurement is the cornerstone.

Problems related to cyberbullying measurement in western studies have been highlighted by multiple researchers. Researchers have some disagreement about the nature of the problem and subsequent solutions.[1],[2],[3],[4] Some researchers have identified the poorly defined “bullying” component of cyberbullying as a major problem,[5],[6] whereas other researchers have discussed the dependence on single-item, definition-based measures rather than multiple-item, behavior-based measures as the problem.[7],[8],[9] Researchers who emphasize the difference between bullying and aggression have debated about what constitutes cyberbullying compared to aggressive cyber behaviors. As discussed in the previous chapter, bullying is traditionally defined as a form of aggression. It is a behavior that threatens to harm or intends to cause harm. Unique features include repetition and chronicity-occurring over time, rather than a single isolated incident. It is highly likely to recur. Other features include an imbalance of power- the perpetrator(s) have some capacity, strength, or power not held by the victim, and the victimized person feels unable to defend themselves.[10],[11] Regardless of how well researchers try to define bullying in measures, two very important points are often neglected: (1) the odds of youth reading a definition very carefully prior to answering questions are most likely to be low. This makes a careful definition potentially meaningless from a practical standpoint; and (2) even if youth are reading a definition, the researchers’ definition may be in opposition to the youth’s existing definition of bullying. Bullying is a household term (at least in English) that may have connotations different from what the researchers intend.[12]

The issues related to terms for and measurement of cyberbullying must be considered in light of the expanding global research on cyberbullying. In general, the English-language literature uses the term cyberbullying, and we have chosen to use the term cyberbullying for our work as well. However, a range of terms have been used, with the desire to most accurately portray the phenomenon of interest (e.g., online harassment, online bullying, internet aggression, cyber aggression, electronic aggression, etc.).[13],[14] Researchers in each language group may need to select the terms and definitions they use to describe similar phenomena based on the cultural context. For example, in Hindi, there is no comparable word for bullying. Dhauns (धौंस) is the closest approximation (a term, used mostly in North India, meaning to use strength or power against someone). People in other language groups may adopt a version of the English “bullying” or adapt other terms to describe this phenomenon.[15] In-depth qualitative research across countries and language groups is necessary to identify the most appropriate, accurate terms to use, and to come to a general agreement about what those terms entail. This work is vital to conduct cross-cultural research and to build a body of research within cultures. For example, if we were to define cyberbullying in a definitional measure in India the same way that we do it in the United States, we may falsely identify a lower rate of occurrence in India. It is possible and maybe likely that there are lower rates of cyberbullying in India than in the U.S. given lower rates of technological adoption. But it is also possible that we simply defined and measured it in a culturally irrelevant manner, making it impossible to accurately estimate its occurrence.

Using a behavior-based measure, rather than a definition-based measure, may be the most effective way to conduct cross-cultural research. Prior research on using the word “bullying” has suggested that the word itself can cause cross-cultural differences in patterns of responding.[16] This problem likely extends to the study of cyberbullying. In addition, using the word “bullying” in a measure (with or without defining it) may reduce the likelihood that children will endorse items in the measure compared to a behavioral checklist without the word “bullying,” This may be due to stigma, socially desirable responding, or an unwillingness to admit vulnerability related to being bullied.[17],[18],[19] Using a behavior-based measure solves multiple problems. For example, asking youth, “How often do you post an embarrassing picture of someone to make fun of them?” provides a much more precise response, without invoking stigma or relying on a cultural conception of cyberbullying, than asking the question, “Have you ever cyberbullied someone?” Similarly, it is possible to compare the rates of response to that question across countries with a relatively low likelihood that different definitions across contexts will evoke a differential response style. That is, it is likely that youth’s responses to that question is indicative of true occurrence of that behavior.

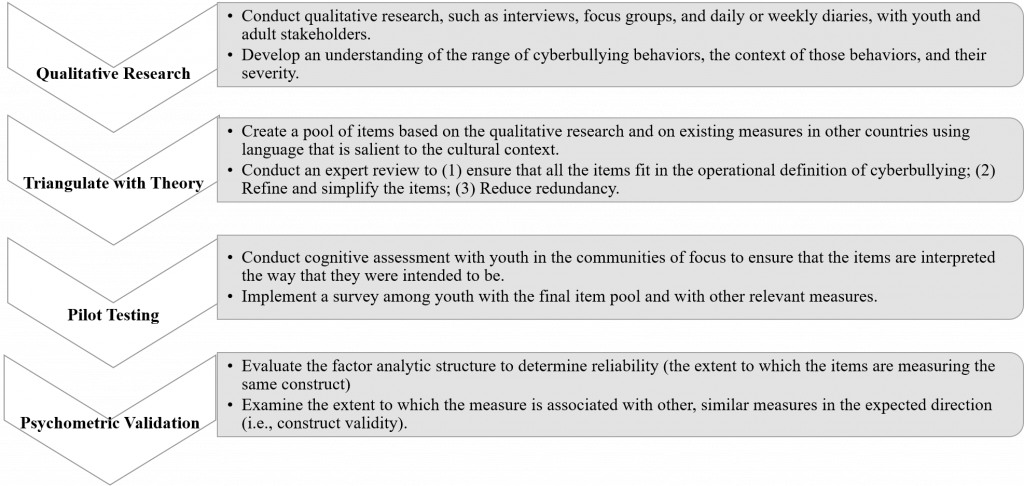

Rich qualitative information is needed to develop behavior-based measures of cyberbullying that allow for cross-national and contextually relevant research. The development of cyberbullying measures across cultures should begin with qualitative research with youth and adult stakeholders. They can provide much-needed insight into the phenomenon of cyberbullying. They can give specific examples of cyberbullying, and the cultural context in which cyberbullying occurs.[20],[21] Key informants should include youth as well as parents, teachers, and other adult stakeholders who have knowledge of cyberbullying incidents. Qualitative data collection can include data collection over time, such as using an ecological momentary assessment approach or a diary reporting method online.[22] Qualitative research should also include in-depth interviews or focus groups. For example, the authors recently conducted an informal focus group as part of a workshop for health professionals in the Delhi area.[23] As part of that workshop, health professionals identified several cultural factors that may shape cyberbullying in India. One of the findings was that youth often use cyber cafes to access the Internet, rather than having personal devices, which can result in true anonymity of perpetration. Similarly, shared devices in a family may be more common in India than in more highly developed countries. In addition, different gender expectations for girls compared to boys, with more restrictions for girls, may result in both more cyberbullying involvement for boys, and more victim-blaming of girls. This is just an example of factors that may influence the phenomenon of cyberbullying and may be important to keep in mind when measuring cyberbullying or identifying its risk factors.

Similarly, the actual behaviors that constitute cyberbullying may occur at different rates across cultures. For example, based on the focus group of health providers in Delhi, some cyberbullying behaviors may be relatively more common in India (e.g., posting anonymous, degrading or insulting comments about fellow students on pages associated with a school; sexual harassment and shaming of girls). On the other hand, some behaviors are almost non-existent in India (e.g., airdropping naked photos of a classmate while in a school cafeteria; threats over online multiplayer gaming systems). Commonly occurring behaviors are likely to significantly vary across cultures, due to a range of factors. Such factors may include access to specific types of electronic communication technologies and devices. Further, poverty, the digital divide and literacy may play a role in what devices are used and how aggression is enacted. Other factors may include informal and formal social control around electronic communications and cultural norms around communication, aggression, rejection, and shaming. Perceptions of what qualities or characteristics of a person “deserve” humiliation or targeted aggression may also play a role in cyberbullying content. For example, characteristics such as weight, gender, caste or social-economic status, region, and language of origin/mother tongue, or behaviors such as sexual behaviors, may be more or less likely to be targets of bullying, depending on cultural context.

To accurately estimate the prevalence of cyberbullying, it is necessary to first gain an understanding of what aggressive behaviors are occurring among youth online. The next step would be to develop a measure that captures those behaviors. This may result in measures that have items that vary in frequency across contexts. When used together, these measures effectively estimate the underlying construct of cyberbullying. Perhaps counterintuitively, simply using the same measures (even translated) that were developed in the Western countries, without doing this measure development groundwork, may result in a measure that assesses different constructs across different contexts.

CYBERBULLYING MEASUREMENT IN ASIA

| Measures of Cyberbullying Perpetration Originally Developed in Asia | |||||

| Authors | Location | Measure & Development | Item Content | Internal Consistency | Construct Validity |

| Cho & Rustu, 2020; Cho & Galehan, 2017; Kim et al., 2017; Jang et al., 2014 | South Korea | Cyberbullying Perpetration; 2 items; no information on development | Spread false information; insulted or cursed | None reported. | Associated with physical bullying. |

| Lee & Shin, 2017 | South Korea | 8 items developed based on prior studies | Perpetration through various media; social exclusion; disclosure of personal information, and coercive behavior | None reported. | Associated with in-person bullying perpetration and cybervictimization. |

| Chan & Wong, 2019; Wong et al., 2014 | Hong Kong | 9 items; theoretically derived | Overt and relational aggression (e.g., spread rumors, used photos to humiliate) | α = .9 | Associated with in-person bullying perpetration. |

| Measures of Cyberbullying Perpetration Adapted for Use in Asian Countries | |||||

| Authors | Location | Measure & Development | Item Content | Internal Consistency | Construct Validity |

| Kwan & Skoric, 2013 | Singapore | 18 items; based on Cassidy et al. (2009) and Hinduja & Patchin (2012) | Perpetration on Facebook, including social exclusion, direct messages, sexually coercive behaviors, hacking, posting embarrassing photos | α = .86 | Associated with in-person bullying, in-person victimization, and cybervictimization |

| Dang & Liu, 2020a,b | China | 11 items; based on the European Cyberbullying Intervention Project Questionnaire | Examples: Said nasty things, threatened someone through texts or online messages | ⍺ = .79 | Associated with pro-cyberbullying attitudes. |

SINGLE-ITEM MEASURES

Single-item measures are measures that try to assess something through just one question or statement. For example, a single item might ask, “Have you ever cyberbullied someone?” Multiple-item measures, in contrast, try to assess something with more than one statement or question (usually at least three). A multiple-item measure for cyberbullying, for example, might have separate questions about how often someone shared embarrassing photos of someone online, sent mean text messages, or threatened someone with messages over a mobile phone or the internet. Single-item measures are fairly common in assessing cyberbullying perpetration in Asia. They have significant limitations, though. With regards to cyberbullying, single-item measures can take multiple forms. For instance, some studies provided a definition of the construct of cyberbullying, followed by a question about the frequency of cyberbullying (e.g., in Bangladesh:[24]). Others simply asked whether an adolescent had harassed or bullied others online without a definition (in South Korea:[25]).

There are multiple problems with using a single-item measure, particularly in assessing variations across cultures or regions. The word “bullied” is not specific. It has different connotations across cultures, with variations in the degree of stigmatization or unacceptability. It is open to subjective interpretation. By using clear-cut, specific, and observable items, researchers can increase the likelihood of an open and honest response by the participating adolescent. This, in turn, will provide a better understanding of the prevalence and the causes of cyberbullying. Through the use of more than one item, the range of behaviors that fall within the realm of cyberbullying could be better assessed. This approach further increases the likelihood of effectively measuring the underlying construct of cyberbullying.

MULTIPLE-ITEM MEASURES

Per classic measurement theory, a multiple-item measure ideally represents a random selection of all possible items in the “universe” of the construct.[26] For example, physical aggression encompasses a universe of behaviors, including kicking, pushing, shoving, slapping, scratching, punching, choking, stabbing, and shooting. It would be nearly impossible to create a measure that includes all physically aggressive behaviors. However, it is possible to identify a random selection of physically aggressive behaviors that can be used to approximate a person’s overall level of physical aggression. In contrast, a single item (e.g., “How often did you punch someone in the last 30 days?”) may be insufficient to effectively estimate a person’s overall level of physical aggression. Using multiple items typically increases reliability (the extent to which items in a measure co-vary) as well as construct validity (the extent to which a measure accurately estimates the construct of interest).[27]

NEED TO ASSESS FACTOR STRUCTURE OF MULTI-ITEM MEASURES

Construct validity is basically how well something measures what it is supposed to measure. For example, there are many ways to measure length. You can use objective measures such as miles, inches, centimeters, or kilometers, or you can use more rough estimates like arms-length or car lengths. Although they all have different names and approaches to measuring distance, they all measure distance. However, if I am using a measure of kilometers but am trying to measure weight, my measure has no construct validity – my goal is to measure weight, but I am actually measuring distance. Similarly, it is possible to think that we are measuring cyberbullying, even when we are not. Because of that, we have to find ways to make sure that when we think that we are measuring cyberbullying, we are actually measuring cyberbullying – and not, for example, in-person bullying, risky online behavior, or even flirting.

Factor analysis is a statistical approach to understanding the construct validity of a measure. In other words, it is a way to use numbers to understand the likelihood that a survey that is supposed to measure cyberbullying is actually measuring cyberbullying and not some other thing. In technical language, factor analysis is based on the premise that the relations among observed or manifest variables (the items on a survey, such as “I posted an embarrassing photo of someone”) can be explained by their membership in a smaller number of unobserved or latent variables (e.g., cyberbullying perpetration). Cronbach and Meehl (1955) described factor analysis as “a most important type of validation” for test development;[28] (p. 286). Factor analysis can not only identify structures within a construct such as cyberbullying (e.g., are there different forms of cyberbullying?) but can also identify the patterns of relations with other factors (e.g., relational aggression, in-person bullying) and possible superordinate factors, or larger categories that cyberbullying fits into (e.g., bullying, aggression).[29] However, most of the existing research on cyberbullying in Asian countries have not explored factor structure.

CYBERBULLYING MEASURES USED IN ASIAN COUNTRIES

In Asia, particularly in India, very little research has followed a rigorous process to develop a measure of cyberbullying. In the emerging research on cyberbullying in Asia, researchers often create their own measures for the purpose of the study. They usually fail to incorporate an appropriate discussion of content and discriminant validity, the process of item creation, the factor analytic structure, and the internal consistency. In other situations, researchers adapt measures developed in other languages for use. The following sections describe cyberbullying measures that have been developed in or adapted for countries in Asia. It also provides a review of the evidence supporting the use of those measures.

The majority of measures developed in Asia for Asian youth have been in use in East Asian countries, including South Korea, Taiwan, and Hong Kong. The measures identified in this literature review are good first steps in extending a cross-cultural understanding of cyberbullying. Right now, it is unclear whether these measures developed in East Asia would be effective in assessing cyberbullying across countries in Asia. Given the heterogeneity of cultures and languages in such a large continent, research should explore the extent to which these measures are effective in other countries and contexts. This is also known as cross-cultural equivalence. As an example, throwing paper balls at someone may be flirting in one culture but a severe insult in another. Measures that have established validity in developed countries such as South Korea and Singapore may not be effective in resource-poor environments. Language and cultural differences may also make it unlikely that measures have cross-cultural equivalence across countries and regions.

MEASURES DEVELOPED IN ASIA

In a study conducted in South Korea, cyberbullying perpetration was measured using Yes or No type questions. The questions were- “Have you ever intentionally circulated false information on the internet message boards about others during the last year?” and “Have you ever cursed/insulted other people through chats/message boards during the last year?” The two questions were summed to create a dichotomous measure that assessed cyberbullying perpetration.[30] This measure was additionally used in three other studies conducted using the Korean Children Youth Panel Survey (KCYPS).[31],[32],[33] There was no description of how the items were developed and selected. There was no explanation of the omission of other potentially common cyberbullying behaviors. There was also minimal assessment of the validity of the measure, such as the extent to which the items were tapping into the same construct (internal consistency). However, some construct validity was established, such that cyberbullying was positively associated with physical bullying.[34]

Similarly, Lee and Shin (2017) created a measure of cyberbullying in South Korea with eight items assessing both perpetration and victimization on a frequency scale. This measure was developed based on previous studies of cyberbullying. Students in this study were also provided with an explanation of cyberbullying. The authors used the term “wangtta,” which is equivalent to bullying, to explain cyberbullying.[35] No indicators of internal consistency were discussed in the study. Youth who reported more cyberbullying perpetration also reported more cyberbullying victimization and more in-person bullying perpetration, suggesting that their measure was effective.[36]

A more comprehensive, theoretically driven measure of cyberbullying has been used to assess cyberbullying in Hong Kong.[37],[38] Their nine-item measure was based on the idea that cyberbullying could be overt (e.g. “maliciously spread fictitious rumors about another person on the internet”) or relational (e.g. “edit and post another person’s photographs on the internet for the purpose of humiliating them”). The internal consistency of the measure was strong (Cronbach’s alpha value of .9). Cyberbullying perpetration was positively related to in-person bullying perpetration. However, future measure validation is necessary to determine whether this measure is associated with other constructs in expected ways, and, ideally, whether it works equally well across countries in the region.

Finally, a study conducted by Jain and colleagues (2020) in India created a new measure for assessing cyberbullying victimization. Perpetration was not included in this study.[39] The researchers in the study identified four activities as acts of cyberbullying- sexual harassment, derogatory comments, stalking, and sharing personal information without consent.[40] However, example items were not included. There was no discussion of internal reliability or other psychometric properties of the measure.

ADAPTED OR TRANSLATED MEASURES

Some researchers developed their own measures to examine cyberbullying in Asia. Most often, researchers adapted other established measures through translation, modification, or adoption of partial items. These studies are varied to the extent in which they assessed for cross-cultural invariance. Cross-cultural invariance is the idea that the measure is just as effective in assessing cyberbullying in different countries, regions, language or ethnic groups.

ADAPTED MEASURES WITH LIMITED RESEARCH ON FACTOR STRUCTURE

In Singapore, Kwan and Skoric (2013) created a measure of cyberbullying based on existing scales.[41],[42],[43] It consisted of 18 items assessing a range of behaviors, such as “I have said things about someone to cause the person to be disliked by his/her friends;” “I have deliberately excluded someone from a Facebook group to make him/her feel left out;” and “I have posted embarrassing photos or videos of someone else on Facebook.” Internal consistency was strong (Cronbach’s ⍺ = .86).[44] Youth who perpetrated cyberbullying had higher rates of in-person bullying, in-person victimization, and cybervictimization.[45] This suggests that their measure of cyberbullying was effective.

In China, the European Cyberbullying Intervention Project Questionnaire[46] was translated into Chinese. It consisted of 11 items assessing cyberbullying (for example, one item was, “I threatened someone through texts or online messages”).[47] Within this study, the measure demonstrated good internal reliability (Cronbach’s ⍺ = .79). No other discussion of the psychometric properties of the adapted measure was provided. Cyberbullying was associated with pro-cyberbullying personal and social attitudes,[48],[49] demonstrating preliminary construct validity.

In Taiwan, Huang and Chou[50] developed a measure assessing cyberbullying perpetration experiences (Cronbach’s ⍺ = .96) based on Kowalski and Limber’s[51] study. The questions were substantially revised to better fit the Taiwanese context following discussion with junior high school students and teachers. The authors discussed issues with translation of the word “bullying,” as the direct Chinese translation (ba-lin) is considerably more negative.[52] Therefore, a longer explanation of cyberbullying with examples was provided to the participants. Additionally, the researchers added some original questions. The number of items and examples of items specifically assessing cyberbullying perpetration were not clear. Cyberbullying perpetration was strongly positively associated with cyberbullying victimization.[53]

Also in Taiwan, Chang and colleagues[54] developed questionnaires based on the U.S. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System and the Youth Internet Safety Survey. These items were then assessed and refined by a group of ten experts from fields such as school bullying, information science technology, digital literacy, health education, and computer education. Cyberbullying perpetration was assessed using six items on a frequency rating scale.[55] Items included “How often have you ever made rude comments to anyone online;” “How often have you ever sent or posted others’ embarrassing photos online;” and “How often have you ever spread rumors about someone online?” A pilot study was conducted to examine responses to the survey and establish reliability.[56] The internal consistency of the newly developed measure was not provided. There was evidence of construct validity; cyberbullying was associated with internet risk behaviors, in-person bullying and depressive symptoms.

In India, a cross-sectional study assessing the prevalence of cyberbullying[57] used the 15-item Cyber Harassment Student Survey.[58] This measure examined an individual’s experience with cyberbullying as the perpetrator. It also examined the victim as well as the emotional and behavioral impact of being cyber-victimized. The original items were developed by Beran and Li[59] based on the researchers’ experiences of working with youth in schools. The survey included a definition of harassment. One item assessed cyberbullying perpetration: “Do you use technology to harass others?” measured on a 5-point rating scale. There was no discussion of the psychometric properties of the measure in India.[60] However, cyberbullying perpetration was associated with cyberbullying victimization, which suggests that this was an effective measure.[61]

An 18-item cyberbullying measure originally developed in Turkey[62] was adapted by the National Youth Policy Institute. It was translated into Korean from Turkish to assess South Korean adolescents’ cyberbullying.[63] The resulting measure had six items. An example item provided was “I send threatening or hurtful comments through e-mail.” The internal consistency was strong (Cronbach’s ⍺ = .89).[64] Construct validity was supported by positive relations with daily Internet use, previous offline bullying and victim experiences, lack of self-control, and aggression. The same Cyberbullying and Cyber Victimization measure[65] was translated to Chinese. It was used by Zhou and colleagues[66] to investigate the risk factors of cyberbullying in adolescents in China. The 18-item, Chinese version had strong internal consistency (Cronbach’s ⍺ = .88). Example behaviors included sending hurtful emails or making threats. Construct validity was supported by positive associations with time spent online, having internet access in one’s bedroom, and in-person bullying perpetration.[67]

ADAPTED MEASURES WITH CROSS-CULTURAL RESEARCH

A cross-cultural study, conducted across China, India, and Japan, studied differences in cyber aggression perpetration and victimization across cultures.[68] Cyber aggression perpetration was assessed using nine items indicating frequency (e.g. “How often do you spread bad rumors about another peer online or through text messages?”). This scale was adapted from a measure assessing in-person relational aggression,[69] previously used in other studies examining cyberbullying perpetration.[70],[71] The measure was translated into the primary language and then back-translated into English. Internal consistency was good across countries (Cronbach’s alphas were .90 for China, .83 for India, and .86 for Japan).[72] Cyberbullying perpetration was associated with in-person victimization, cybervictimization and in-person bullying across China, Japan, and India,[73] providing some evidence of construct validity. They did not report on the factor structure. In addition, cross-cultural equivalence was not described.

A cross-cultural study conducted with samples from the United States and Japan assessed cyberbullying frequency. This study adapted Ybarra and colleagues’[74] Cyber Behavioral Questionnaire.[75] The scale consisted of 3 items (“send threatening or aggressive comments to anyone online”, “send rude or nasty comments to anyone online”, “target someone with rumors spread online, whether they were true or not”), with higher scores indicating greater frequencies of cyberbullying.[76] The measure, originally developed in the U.S., was translated from English to Japanese, and back-translated to ensure consistency.[77] Item equivalence testing was conducted where each individual item was investigated for cultural differences. One item demonstrated minor differences indicating that people may have responded differently to the item based on country of origin.[78] The internal consistency was stated to be similar between Japanese and U.S. samples, but numbers were not provided. Cyberbullying perpetration was found to be associated with positive attitudes toward cyberbullying. It was also found to be associated with positive reinforcement of cyberbullying.[79]

A study conducted in U.S. and Singaporean samples[80] used a nine-item cyberbullying questionnaire (e.g. “I made fun of someone by sending/posting stories, jokes, or pictures about him/her”).[81] The nine-item measure used in this study, developed by Ang and Goh,[82] was based on the concept that cyberbullying consists of deception (pretending to be someone), broadcasting (spreading jokes, rumors, or stories about a person), and targets online action (sending mean or threatening messages). The measure had good internal consistency in the U.S. sample (⍺ = .91) and Singapore sample (⍺ = .84). Both exploratory (open-ended) and confirmatory factor analysis (theory-based analysis) were used for validation.[83] Multigroup confirmatory factor analysis found that the measure worked equally well across genders.[84] Cyberbullying was negatively related to empathy[85], and positively related to reactive and proactive aggression[86], providing preliminary support for construct validity.

We translated the cyberbullying perpetration and victimization scales of the Problem Behaviors Frequency Scales – Adolescent Revised (PBFS-AR)[87] to Hindi. Some item-level adaptations were made to be appropriate to the Indian context. It consisted of 22 items and measured both cyberbullying perpetration and cybervictimization (see the Appendix for the full scales in English and Hindi). We then implemented a survey with participants from U.S. (10-14 years old) and India (ages 9-15). Of note, estimates of cyberbullying and cybervictimization were high in India. More than one-third of youth (35%) reported engaging in at least one cyberbullying behavior in the past 30 days, and 34% reported experiencing at least one instance of cybervictimization in the past 30 days. We found strong cross-cultural internal validity as measured by Cronbach’s α (cyberbullying α = .96 [India]; .94 [U.S.]; cybervictimization α =.93 [India]; .94 [U.S]). We also found evidence of measurement invariance across cultures. Concurrent validity was demonstrated by the association of cyberbullying with physical and relational aggression and the association of cybervictimization with physical and relational victimization. Overall, the adapted PBFS-AR is likely to effectively measure cyberbullying and cybervictimization in India. The extent to which this may generalize to other countries in Asia is unknown.

In the following chapters, we elaborate on cyberbullying prevention and response. Chapter three covers individual level determinants, relationships with peers and their effect on cyberbullying behavior. This chapter also conveys the role of school as a community level organization in preventing cyberbullying. Understanding school- and peer-level factors is important in preventing cyberbullying events and mitigating its potentially harmful impacts. By far these are the most studied factors addressed in interventions to prevent cyberbullying.

CONCLUSION

Cyberbullying is an emerging area of research in Asia. Gold standard measures of cyberbullying, with evidence of cross-cultural validity, is vital to effective measurement of cyberbullying. These measures, when established, can be used to understand the prevalence of cyberbullying. They can also be used to identify outcomes associated with cyberbullying and to explore malleable risk and protective factors. As of now, there is limited information about the measures of cyberbullying that are currently being used in Asia. The measures with the most evidence include Ang and Goh’s (2010) measure, which appears to work well in both the U.S. and Singapore;[88],[89] Ybarra and colleagues’ (2007) measure, which appears to work well in the U.S. and Japan;[90],[91] and Wong, Chan, and colleagues’ measure, which has been studied in Hong Kong.[92],[93] The research on cyberbullying in Asia has heavily occurred in East Asia, but research in South Asia, Southeast Asia, and Central Asia is insufficient to draw concrete conclusions.

To establish strong measures, future research can: (1) work to establish the effectiveness of existing measures; or (2) work to develop new measures or adapt existing measures using a ground-up approach. Using a mixed methods approach is very useful both in initial measure development and in adaptations of measures.[94],[95] For example, using qualitative research, such as through interviews or focus groups, makes it possible to explore a range of cyberbullying behaviors that occur in adolescents’ contexts. This approach ensures that commonly occurring cyberbullying behaviors are identified. For example, focus groups in India suggest that one commonly occurring behavior is posting insults or slander about someone else on school-specific anonymous boards.[96] Given this finding, it may be important to add an item assessing this to any cyberbullying measure that is being used in India. Overall, using qualitative research to bring to light local or regional manifestations of cyberbullying will make it possible to develop measures of cyberbullying that capture the range of behaviors that occur in that specific context. Once the items on a measure are finalized, it is important to examine the validity of the measure by determining how well the items go together, the extent to which the measure works equally well across ethnic or linguistic groups, and the extent to which the measure is associated with other related variables.

KEY TAKE-AWAYS

- Overall, cyberbullying is a moving target, with rapid changes in electronic communication technologies enabling new forms of aggression.

- Cultural factors may play a strong role in what cyberbullying behaviors occur and are common.

- Effective measurement development and testing strategies are needed to enable accurate cyberbullying research.

- Scales with multiple behavior-based items and without explicit use of the word “cyberbullying” are more likely to be effective cross-culturally.

- Mehari KR, Farrell AD, Le AH. Cyberbullying among adolescents: Measures in search of a construct. Psychology of Violence 2014;4(4):399. ↵

- Tokunaga RS. Following you home from school: A critical review and synthesis of research on cyberbullying victimization. Comput Hum Behav 2010;26(3):277-287. ↵

- Olweus D. Cyberbullying: An overrated phenomenon? European journal of developmental psychology 2012;9(5):520-538. ↵

- Menesini E. Cyberbullying: The right value of the phenomenon. Comments on the paper “Cyberbullying: An overrated phenomenon?”. European journal of developmental psychology 2012;9(5):544-552. ↵

- Olweus D. Cyberbullying: An overrated phenomenon? European journal of developmental psychology 2012;9(5):520-538. ↵

- Menesini E. Cyberbullying: The right value of the phenomenon. Comments on the paper “Cyberbullying: An overrated phenomenon?”. European journal of developmental psychology 2012;9(5):544-552. ↵

- Mehari KR, Farrell AD, Le AH. Cyberbullying among adolescents: Measures in search of a construct. Psychology of Violence 2014;4(4):399. ↵

- Tokunaga RS. Following you home from school: A critical review and synthesis of research on cyberbullying victimization. Comput Hum Behav 2010;26(3):277-287. ↵

- Enter your footnote Ybarra ML, Boyd D, Korchmaros JD, Oppenheim JK. Defining and measuring cyberbullying within the larger context of bullying victimization. Journal of Adolescent Health 2012;51(1):53-58.here. ↵

- Gladden RM, Vivolo-Kantor AM, Hamburger ME, Lumpkin CD. Bullying surveillance among youths: Uniform definitions for public health and recommended data elements. 2014. ↵

- Solberg ME, Olweus D. Prevalence estimation of school bullying with the Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire. Aggressive Behav 2003;29(3):239-268. ↵

- Moreno MA, Suthamjariya N, Selkie E. Stakeholder perceptions of cyberbullying cases: application of the uniform definition of bullying. Journal of Adolescent Health 2018;62(4):444-449. ↵

- Williams KR, Guerra NG. Prevalence and predictors of internet bullying. Journal of adolescent health 2007;41(6):S14-S21. ↵

- Ybarra ML, Mitchell KJ. Prevalence and frequency of Internet harassment instigation: Implications for adolescent health. Journal of Adolescent Health 2007;41(2):189-195. ↵

- Smith PK, Cowie H, Olafsson RF, Liefooghe AP. Definitions of bullying: A comparison of terms used, and age and gender differences, in a Fourteen–Country international comparison. Child Dev 2002;73(4):1119-1133. ↵

- Konishi C, Hymel S, Zumbo BD, Li Z, Taki M, Slee P, et al. Investigating the comparability of a self-report measure of childhood bullying across countries. Canadian Journal of School Psychology 2009;24(1):82-93. ↵

- Ybarra ML, Boyd D, Korchmaros JD, Oppenheim JK. Defining and measuring cyberbullying within the larger context of bullying victimization. Journal of Adolescent Health 2012;51(1):53-58. ↵

- Sontag LM, Graber JA, Clemans KH. The role of peer stress and pubertal timing on symptoms of psychopathology during early adolescence. Journal of youth and adolescence 2011;40(10):1371-1382. ↵

- Nocentini A, Menesini E. Cyberbullying definition and measurement. Zeitschrift für Psychologie/Journal of Psychology 2009;217(4):230-232. ↵

- Mehari KR, Farrell AD, Le AH. Cyberbullying among adolescents: Measures in search of a construct. Psychology of Violence 2014;4(4):399. ↵

- Mishna F, Saini M, Solomon S. Ongoing and online: Children and youth's perceptions of cyber bullying. Children and Youth Services Review 2009;31(12):1222-1228. ↵

- Dear diary: Teens reflect on their weekly online risk experiences. Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; 2016. ↵

- Sharma D, Mehari KR, Doty JL. Stakeholder Focus Groups on Cyberbullying in India. 2021. ↵

- Sarker S, Shahid AR. Cyberbullying of high school students in bangladesh: an exploratory study. arXiv preprint arXiv:1901.00755 2018. ↵

- Shin N, Ahn H. Factors affecting adolescents' involvement in cyberbullying: what divides the 20% from the 80%? Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 2015;18(7):393-399. ↵

- Nunnally JC. Psychometric theory 3E.: Tata McGraw-hill education; 1994. ↵

- DeVellis RF. Scale development: Theory and applications (Vol. 26). 2016. ↵

- Cronbach LJ, Meehl PE. Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychol Bull 1955;52(4):281. ↵

- Mehari KR, Farrell AD, Le AH. Cyberbullying among adolescents: Measures in search of a construct. Psychology of Violence 2014;4(4):399. ↵

- Cho S, Rustu D. Examining the impacts of low self-control and online lifestyles on cyberbullying perpetration among Korean adolescents: Using parallel process latent growth curve modeling. Children and Youth Services Review 2020;117:105288. ↵

- Cho S, Rustu D. Examining the impacts of low self-control and online lifestyles on cyberbullying perpetration among Korean adolescents: Using parallel process latent growth curve modeling. Children and Youth Services Review 2020;117:105288. ↵

- Kim J, Song H, Jennings WG. A distinct form of deviance or a variation of bullying? Examining the developmental pathways and motives of cyberbullying compared with traditional bullying in South Korea. Crime & Delinquency 2017;63(12):1600-1625. ↵

- Jang H, Song J, Kim R. Does the offline bully-victimization influence cyberbullying behavior among youths? Application of general strain theory. Comput Hum Behav 2014;31:85-93. ↵

- Jang H, Song J, Kim R. Does the offline bully-victimization influence cyberbullying behavior among youths? Application of general strain theory. Comput Hum Behav 2014;31:85-93. ↵

- Lee C, Shin N. Prevalence of cyberbullying and predictors of cyberbullying perpetration among Korean adolescents. Comput Hum Behav 2017;68:352-358. ↵

- Lee C, Shin N. Prevalence of cyberbullying and predictors of cyberbullying perpetration among Korean adolescents. Comput Hum Behav 2017;68:352-358. ↵

- Chan HC, Wong DS. Traditional school bullying and cyberbullying perpetration: Examining the psychosocial characteristics of Hong Kong male and female adolescents. Youth & Society 2019;51(1):3-29. ↵

- Wong DS, Chan HCO, Cheng CH. Cyberbullying perpetration and victimization among adolescents in Hong Kong. Children and youth services review 2014;36:133-140. ↵

- Jain O, Gupta M, Satam S, Panda S. Has the COVID-19 pandemic affected the susceptibility to cyberbullying in India? Computers in Human Behavior Reports 2020;2:100029. ↵

- Jain O, Gupta M, Satam S, Panda S. Has the COVID-19 pandemic affected the susceptibility to cyberbullying in India? Computers in Human Behavior Reports 2020;2:100029. ↵

- Kwan GCE, Skoric MM. Facebook bullying: An extension of battles in school. Comput Hum Behav 2013;29(1):16-25. ↵

- Cassidy W, Brown K, Jackson M. “Making Kind Cool”: Parents' Suggestions for Preventing Cyber Bullying and Fostering Cyber Kindness. Journal of Educational Computing Research 2012;46(4):415-436. ↵

- Patchin JW, Hinduja S. Cyberbullying and self‐esteem. J Sch Health 2010;80(12):614-621. ↵

- Kwan GCE, Skoric MM. Facebook bullying: An extension of battles in school. Comput Hum Behav 2013;29(1):16-25. ↵

- Kwan GCE, Skoric MM. Facebook bullying: An extension of battles in school. Comput Hum Behav 2013;29(1):16-25. ↵

- Brighi A, Ortega R, Pyzalski J, Scheithauer H, Smith P, Tsormpatzoudis H, et al. European cyberbullying intervention project questionnaire (ECIPQ). Unpublished questionnaire 2012. ↵

- Dang J, Liu L. When peer norms work? Coherent groups facilitate normative influences on cyber aggression. Aggressive Behav 2020;46(6):559-569. ↵

- Dang J, Liu L. When peer norms work? Coherent groups facilitate normative influences on cyber aggression. Aggressive Behav 2020;46(6):559-569. ↵

- Dang J, Liu L. Me and Others Around: The Roles of Personal and Social Norms in Chinese Adolescent Bystanders’ Responses Toward Cyberbullying. J Interpers Violence 2020:0886260520967128. ↵

- Huang Y, Chou C. An analysis of multiple factors of cyberbullying among junior high school students in Taiwan. Comput Hum Behav 2010;26(6):1581-1590. ↵

- Kowalski RM, Limber SP. Electronic bullying among middle school students. Journal of adolescent health 2007;41(6):S22-S30. ↵

- Huang Y, Chou C. An analysis of multiple factors of cyberbullying among junior high school students in Taiwan. Comput Hum Behav 2010;26(6):1581-1590. ↵

- Huang Y, Chou C. An analysis of multiple factors of cyberbullying among junior high school students in Taiwan. Comput Hum Behav 2010;26(6):1581-1590. ↵

- Chang F, Lee C, Chiu C, Hsi W, Huang T, Pan Y. Relationships among cyberbullying, school bullying, and mental health in Taiwanese adolescents. J Sch Health 2013;83(6):454-462. ↵

- Chang F, Lee C, Chiu C, Hsi W, Huang T, Pan Y. Relationships among cyberbullying, school bullying, and mental health in Taiwanese adolescents. J Sch Health 2013;83(6):454-462. ↵

- Chang F, Lee C, Chiu C, Hsi W, Huang T, Pan Y. Relationships among cyberbullying, school bullying, and mental health in Taiwanese adolescents. J Sch Health 2013;83(6):454-462. ↵

- Sharma D, Kishore J, Sharma N, Duggal M. Aggression in schools: cyberbullying and gender issues. Asian journal of psychiatry 2017;29:142-145. ↵

- Beran T, Li Q. Cyber-harassment: A study of a new method for an old behavior. Journal of educational computing research 2005;32(3):265. ↵

- Beran T, Li Q. Cyber-harassment: A study of a new method for an old behavior. Journal of educational computing research 2005;32(3):265. ↵

- Sharma D, Kishore J, Sharma N, Duggal M. Aggression in schools: cyberbullying and gender issues. Asian journal of psychiatry 2017;29:142-145. ↵

- Sharma D, Kishore J, Sharma N, Duggal M. Aggression in schools: cyberbullying and gender issues. Asian journal of psychiatry 2017;29:142-145. ↵

- Erdur Ö, Kavşut F. A new face of peer bullying: cyber bullying. Journal of Euroasian Educational Research 2007;27:31-42. ↵

- You S, Lim SA. Longitudinal predictors of cyberbullying perpetration: Evidence from Korean middle school students. Personality and Individual Differences 2016;89:172-176. ↵

- You S, Lim SA. Longitudinal predictors of cyberbullying perpetration: Evidence from Korean middle school students. Personality and Individual Differences 2016;89:172-176. ↵

- Erdur Ö, Kavşut F. A new face of peer bullying: cyber bullying. Journal of Euroasian Educational Research 2007;27:31-42. ↵

- Zhou Z, Tang H, Tian Y, Wei H, Zhang F, Morrison CM. Cyberbullying and its risk factors among Chinese high school students. School psychology international 2013;34(6):630-647. ↵

- Zhou Z, Tang H, Tian Y, Wei H, Zhang F, Morrison CM. Cyberbullying and its risk factors among Chinese high school students. School psychology international 2013;34(6):630-647. ↵

- Wright MF, Aoyama I, Kamble SV, Li Z, Soudi S, Lei L, et al. Peer attachment and cyber aggression involvement among Chinese, Indian, and Japanese adolescents. Societies 2015;5(2):339-353. ↵

- Crick NR, Grotpeter JK. Relational aggression, gender, and social‐psychological adjustment. Child Dev 1995;66(3):710-722. ↵

- Wright MF, Huang Z, Wachs S, Aoyama I, Kamble S, Soudi S, et al. Associations between cyberbullying perpetration and the dark triad of personality traits: the moderating effect of country of origin and gender. Asia Pacific Journal of Social Work and Development 2020;30(3):242-256. ↵

- Wright MF, Li Y. Kicking the digital dog: A longitudinal investigation of young adults' victimization and cyber-displaced aggression. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 2012;15(9):448-454. ↵

- Wright MF, Huang Z, Wachs S, Aoyama I, Kamble S, Soudi S, et al. Associations between cyberbullying perpetration and the dark triad of personality traits: the moderating effect of country of origin and gender. Asia Pacific Journal of Social Work and Development 2020;30(3):242-256. ↵

- Wright MF, Aoyama I, Kamble SV, Li Z, Soudi S, Lei L, et al. Peer attachment and cyber aggression involvement among Chinese, Indian, and Japanese adolescents. Societies 2015;5(2):339-353. ↵

- Ybarra ML, Mitchell KJ. Prevalence and frequency of Internet harassment instigation: Implications for adolescent health. Journal of Adolescent Health 2007;41(2):189-195. ↵

- Barlett CP, Gentile DA, Anderson CA, Suzuki K, Sakamoto A, Yamaoka A, et al. Cross-cultural differences in cyberbullying behavior: A short-term longitudinal study. Journal of cross-cultural psychology 2014;45(2):300-313. ↵

- Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, Ross J, Hawkins J, Harris WA, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2005. J Sch Health 2006;76(7):353-372. ↵

- Barlett CP, Gentile DA, Anderson CA, Suzuki K, Sakamoto A, Yamaoka A, et al. Cross-cultural differences in cyberbullying behavior: A short-term longitudinal study. Journal of cross-cultural psychology 2014;45(2):300-313. ↵

- Barlett CP, Gentile DA, Anderson CA, Suzuki K, Sakamoto A, Yamaoka A, et al. Cross-cultural differences in cyberbullying behavior: A short-term longitudinal study. Journal of cross-cultural psychology 2014;45(2):300-313. ↵

- Barlett CP, Gentile DA, Anderson CA, Suzuki K, Sakamoto A, Yamaoka A, et al. Cross-cultural differences in cyberbullying behavior: A short-term longitudinal study. Journal of cross-cultural psychology 2014;45(2):300-313. ↵

- Wolak J, Mitchell KJ, Finkelhor D. Online Victimization of Youth: Five Years Later. 2006. ↵

- Ang RP, Huan VS, Florell D. Understanding the relationship between proactive and reactive aggression, and cyberbullying across United States and Singapore adolescent samples. J Interpers Violence 2014;29(2):237-254. ↵

- Ang RP, Goh DH. Cyberbullying among adolescents: The role of affective and cognitive empathy, and gender. Child Psychiatry & Human Development 2010;41(4):387-397. ↵

- Ang RP, Goh DH. Cyberbullying among adolescents: The role of affective and cognitive empathy, and gender. Child Psychiatry & Human Development 2010;41(4):387-397. ↵

- Ang RP, Goh DH. Cyberbullying among adolescents: The role of affective and cognitive empathy, and gender. Child Psychiatry & Human Development 2010;41(4):387-397. ↵

- Ang RP, Goh DH. Cyberbullying among adolescents: The role of affective and cognitive empathy, and gender. Child Psychiatry & Human Development 2010;41(4):387-397. ↵

- Ang RP, Huan VS, Florell D. Understanding the relationship between proactive and reactive aggression, and cyberbullying across United States and Singapore adolescent samples. J Interpers Violence 2014;29(2):237-254. ↵

- Farrell AD, Thompson EL, Mehari KR, Sullivan TN, Goncy EA. Assessment of in-person and cyber aggression and victimization, substance use, and delinquent behavior during early adolescence. Assessment 2020;27(6):1213-1229. ↵

- Ang RP, Huan VS, Florell D. Understanding the relationship between proactive and reactive aggression, and cyberbullying across United States and Singapore adolescent samples. J Interpers Violence 2014;29(2):237-254. ↵

- Ang RP, Goh DH. Cyberbullying among adolescents: The role of affective and cognitive empathy, and gender. Child Psychiatry & Human Development 2010;41(4):387-397. ↵

- Ybarra ML, Mitchell KJ. Prevalence and frequency of Internet harassment instigation: Implications for adolescent health. Journal of Adolescent Health 2007;41(2):189-195. ↵

- Barlett CP, Gentile DA, Anderson CA, Suzuki K, Sakamoto A, Yamaoka A, et al. Cross-cultural differences in cyberbullying behavior: A short-term longitudinal study. Journal of cross-cultural psychology 2014;45(2):300-313. ↵

- Chan HC, Wong DS. Traditional school bullying and cyberbullying perpetration: Examining the psychosocial characteristics of Hong Kong male and female adolescents. Youth & Society 2019;51(1):3-29. ↵

- Wong DS, Chan HCO, Cheng CH. Cyberbullying perpetration and victimization among adolescents in Hong Kong. Children and youth services review 2014;36:133-140. ↵

- Mehari KR, Farrell AD, Le AH. Cyberbullying among adolescents: Measures in search of a construct. Psychology of Violence 2014;4(4):399. ↵

- Mishna F, Saini M, Solomon S. Ongoing and online: Children and youth's perceptions of cyber bullying. Children and Youth Services Review 2009;31(12):1222-1228. ↵

- Sharma D, Mehari KR, Doty JL. Stakeholder Focus Groups on Cyberbullying in India. 2021. ↵