1 Chapter I: Prelude

In the middle of the nineteenth century, the Republic of Texas was an anomaly, a transition area between the established South and the frontier West. Much of western and northern Texas was wilderness, piney woods and swamplands where Indian tribes lived undisturbed by the scattered squatters and hunters whose connections to civilization were remote and whose allegiance was to themselves alone. East Texas, though more populous, still had about it a wild and woolly frontier flavor. In these days before statehood it was a haven for persons fleeing the laws of neighboring states. But though it lacked civility, it abounded in opportunity, a wide open area, ripe for enterprising men from older, more established regions where the land had already been cleared, the class system installed, a man’s opportunities somewhat circumscribed. For the ambitious Southern farmer East Texas was the new frontier, lacking the laws that prevented expansion and the customs that limited unabashed ambition, but in its climate and geography little more than a fresh extension of the South.

The land was rich and fertile, the delightfully mild climate perfect for agriculture. Breezes from the Gulf of Mexico modified the summer heat and produced sufficient and evenly distributed rainfall as well as an active wind movement. Already, cotton was becoming the major cash crop of the region. Areas not cleared for agriculture were richly timbered with pine, oak, hickory, ash, gum, cottonwood, and cypress trees, and the lumber business provided another practically untapped opportunity for the enterprising immigrant. Charles Moores intended to go into farming as well as the lumber business when at the age of sixty-two he left the area near Longtown, Fairfield County, South Carolina, with his sons Eli, twenty-three, and Reuben, twenty-one, to purchase land and establish a homestead for his family. They arrived in East Texas in February 1838 and acquired the John Jackson and Howard Ethridge and part of the E. T. Jackson headright surveys in the area now known as Red Springs in Bowie County. (1) It was wooded, fertile land with abundant water. Several streams as well as Barr’s Creek would provide water for the home and mill they intended to build, and Trammels Trace (2) was already an established main road for the post office and small store planned for the village that would be called Mooresville. They built a house, purchased one or two slaves, and about a year and a half later Charles Moores returned to South Carolina for the rest of the family. During his absence, Eli and Reuben cleared the land intended for cultivation and built additional living quarters.

Charles Moores, his wife Mary Harrison Moores, and their children, including sons Thomas, twenty, and Anderson, eighteen, set out for Texas in February 1840, leading a sizable entourage of other families, livestock, and slaves. A daughter, Nancy, age thirty, and her husband James Rochelle, remained in South Carolina, where they owned slaves and operated a farm of their own. The Moores party traveled by oxcart, wagon train, and carriage during their more than three-month journey. During a stop at Bell Buckle, Tennessee, Thomas Moores met and married Sarah Norvell, who joined the group as they continued westward. They arrived at their new home on May 24, 1840. (3)

The Moores house fronted on a lake and was built of logs hand-hewn to resemble clapboards. The kitchen and smokehouse were separate buildings and a slave quarter was erected some yards behind the house. After the rest of the family and their fellow travelers arrived, Mooresville took shape quickly. It was officially recognized as a postal depot in 1841, and Reuben Moores served as the first postmaster. Immediately upon her arrival, Mary Harrison Moores asked that a church be erected, which she named Harrison Chapel in memory of her parents. Similar in appearance to the Moores house, it had glass windows and a balcony reserved for slaves. After it was destroyed by fire, in 1842 another church was organized at Mooresville by Methodist circuit rider J. W. P. McKenzel.

By the time of the 1846–48 Mexican War over Texas, which was admitted to the Union in 1845, Mooresville had become a village of sorts. Major J. P. Gaines, whose cavalry regiment from Kentucky camped at Mooresville, wrote in his diary, “Marched 20 miles from Red River to Moores, ticks innumerable, a good plantation, and a wealthy man, store, grog shop . . . Bought an old-fashioned splint bottom chair for which I paid one dollar.” (4) By 1848 Charles Moores owned 6,625 acres of land which stretched toward the Sulphur River, where Moores Landing adjoined the James Giles headright in Cass County. He was wealthy, as Major Gaines had noted, and though it is likely that he would have returned to South Carolina to get his daughter’s children and property under any circumstances, his wealth made it considerably easier for him to do so.

Nancy Moores Rochelle had died in February 1843. Her husband, James, died early in 1850, leaving not only four sons and a daughter but slaves and other property as well. Shortly after receiving word of James Rochelle’s death, Charles Moores left Texas for South Carolina to get the Rochelle children and property. He arrived back in Texas with his charges in late August 1850. (5) The grandchildren, John, Charles, Henry, Eugene, and Mary, were welcomed by the large, extended family that comprised Mooresville, a family related both by blood ties and by their common ties to the land on which they had settled just a decade before. The slaves, too, were welcomed by their fellow slaves, who took particular care to make the new children feel welcome, for they were unused to the strange country so many hundreds of miles away from home. One of these new slave children was named Jiles. (6) A small boy of medium dark color, Jiles was shortly to be accorded a type of respect to which slaves in Texas, or in any other slave state for that matter, were rarely privileged. In September 1850 his name would be recorded in a census.

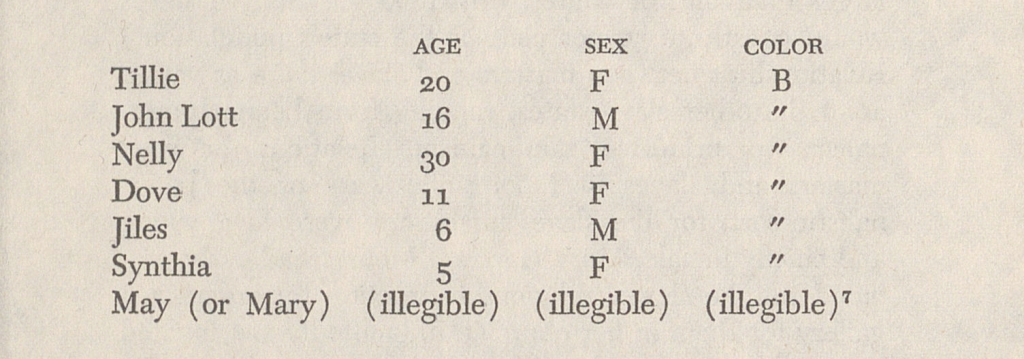

Just a few weeks after Charles Moores’s return, Mooresville was visited by a census taker, whose duty was to record the number of slaves in Bowie County. Under the “Three-Fifths Compromise,” slave states were accorded representation for three-fifths of their slave population in addition to that for their white population. Thus, every ten years a slave census was taken in all the counties of the slave states. The purpose of the slave census, unlike that of the federal census, was to record numbers, ages, and sexes, not names. There was not even a blank on the census form for the slaves’ names, and yet in that year Bowie County census taker Benjamin Booth did record the names of slaves. This is what he listed under the name Chas. Moores:

Charles Moores had not been back in Mooresville long before he was visited by Benjamin Booth, and undoubtedly he was surprised by Booth’s request for the names of his slaves. He had little trouble remembering their names, for he had only a few, but their ages were more difficult to ascertain, particularly those of the slaves newly brought from South Carolina. When asked Jiles’s age, he thought for a moment, considered the boy’s small stature, and gave his age as six. Actually, Jiles was probably about eight. (8)

By the time young Jiles arrived in East Texas, that area had acquired considerable stability and homogeneity of population. Although there was a constant influx of people, they were primarily from the older Southern states, especially Alabama and the other states along the Gulf of Mexico. These people had brought their customs with them, and by 1850, East Texas was simply a younger version of the South, its economic and social systems those of the established Southern states. Slaves were an integral part of these systems and comprised more than a third of the state’s population. In Bowie County, according to the 1850 census, there were 1,641 slaves. In some counties in eastern and southeastern Texas the slave population was larger than that of whites. (By 1860 the 182,566 slaves would constitute 50 per cent of the state’s population.) Relationships between masters and slaves were as varied as in the other slave states, ranging from benign paternalism to primitive inhumanism. Relations between masters and slaves in Mooresville were of the paternalistic sort, for the slave inhabitants were few, young and chiefly female. Mary Harrison Moores had early provided for the slaves’ religious instruction by ordering a gallery for them in her church. Undoubtedly she insisted on a similar area for slave worship in the new church that was built after the Harrison Chapel was destroyed by fire. The Rochelle slaves were especially well treated, for they and their offspring would become the property of the Rochelle children when they came of age. Charles Moores held them in trust for his grandchildren until he died in 1852, whereupon trusteeship of these slaves passed to other family members until the grandchildren reached their majority. (9)

Jiles grew up in relative comfort. When he arrived at Mooresville, he was too young to work in the fields, and he was assigned chores in and around the house. There was much to do to keep up the Moores home-place. It was a frequent gathering spot for neighbors in the surrounding area, among them the families of Elliott, Whitaker, Jarrett, and Hooks. Extra rooms above the main hall were kept especially for circuit preachers, itinerant peddlers, and other travelers. Often the large hall hosted dances, the steps leading to the upper rooms conveniently serving as a box for the string band on such occasions. When he was young, Jiles acted as a serving boy to the guests, watching with fascination as the dancers tripped through their complex square dance routines and polka-like schottisches while the musicians played. Even an experienced observer here would be hard put to differentiate the music and dancing from those of established South Carolina society. This was especially true of the music. Almost entirely European in character, it had undergone no more change in its transplantation from South Carolina to Texas than it had from Europe to America. Jiles showed an aptitude, for this music, and particularly for the violin, and when he was old enough he became part of the plantation’s string band, standing on the stairs leading up from the main hall and playing for the colorfully dressed dancers below. (10)

Mooresville was not very different from any small Southern plantation area, although there was far greater opportunity for land expansion, and the slave population grew accordingly. By the mid-1850s, however, considerable differences could be seen, for East Texas, unlike the other slave regions to the east, did not feel many of the tensions that resulted from the heightened hostility between North and South that was to lead to the formation of the Confederacy and the outbreak of the Civil War. Mooresville prospered. As children married, they were given tracts of land on which they built homes of their own and which they worked for income to buy more land. In 1847, when Eli Moores had married, Charles Moores had deeded 166 acres of the Howard Ethridge headright survey to his son, an area that would later be come part of Texarkana, Texas.

A few miles away from Mooresville, the village of Hooks was enjoying a similar period of rapid growth. Warren and Elizabeth Roberts Hooks had come to East Texas from North Carolina by way of Alabama. (11) Like Charles Moores, Warren Hooks had gone west searching for land and greater opportunity, had cleared acres of land for farming and built a sawmill, purchased slaves, (12) and expanded his family holdings through his children. Hooks children and grandchildren intermarried with Moores and Rochelle children and grandchildren, and the families exchanged gifts and entered into business dealings with each other. Probably sometime in the late 1850s the Mooreses’ slave Jiles left Mooresville and became part of the household of Warren Hooks, perhaps as a wedding gift to Warren’s daughter, Minerva. Minerva married a man named Josiah Joplin, and it was this man’s last name that Jiles took as his own. (13)

Jiles did not stay long in the Hooks household. Although it is not known when or under what circumstances, Jiles was freed when he was in his late teens, several years before the Emancipation Proclamation was issued in Texas. (14) He could probably have remained in the relatively benign atmosphere of Hooks and Mooresville, but he chose instead to travel south, perhaps intending to make his way to one of the large cities. Near the area around present-day Linden he met Florence Givins, and he changed his mind.

Florence Givins had been freeborn in Kentucky (15) in 1841 and had traveled with her father, Milton, and her grandmother, Susan, to Texas, where the family served in the capacity of slave overseers for white farmers. (16) Florence was a comely young woman, a year older than Jiles and sufficiently shorter in height to bolster the ego of this man who is said to have been very short. Though she might have preferred a husband who had been born free, as she had been, such men were scarce in rural Texas, and at least Jiles was a freedman. At the ages of about eighteen and nineteen respectively, Jiles Joplin and Florence Givins entered into the only marriage-like arrangement available to most Blacks, slave or free, at that time. As Zenobia Campbell, who knew the Joplins in Texarkana, once said, “Back then, colored people didn’t pay much attention to marriage and divorce. When they married, they just jumped over the broomstick.” (17) Their first child, Monroe, was born just as the Civil War was breaking out. (18)

With Arkansas, Texas seceded from the Union in 1861. During the war Marshall, Texas, became the Confederate capital-in-exile of Missouri, and North Texas became an important area for Missouri slaveowners. But Texas was never a major campaign front, and while it felt some economic effects from the war that raged to the east of it—closed ports and trails and the halting of railroad construction—it was not blanketed by the propaganda that accompanied the slavery question in the states to the east. For the most part, slaves in East Texas hardly knew their freedom was at issue.

The Joplins lived as they had prior to the war, working in the fields, living day to day with little hope for the future and little understanding of the war’s implications for their lives. Nor were whites in East Texas particularly affected. The cotton plantations and timber businesses continued production, and though shipping was circumscribed the planters and millowners did not suffer inordinately. Both products could be stored for long periods of time while waiting for a mule-drawn wagon to take them to Jefferson, Texas, or for a riverboat to get through a federal blockade or arrive by a more circuitous route; and since these steamboats with their wide, flat guards, had a capacity of from one thousand to two thousand bales of cotton they could frequently accommodate a large portion of the region’s crop. Although the arrival of a steamboat in the towns along the rivers was always an occasion, during the war years it was especially so. When a boat arrived during the day, nearby slaves were allowed to interrupt their work to go down to the dock and witness its landing. At night, the slaves lit pine knot torches to facilitate the docking, the excitement of the event heightened by the flickering lights. The arrival of a steamboat was a welcome interruption in the monotony of their lives.

On June 19, 1865, the Emancipation Proclamation was issued at Galveston. It came as no surprise to most Texans, for the so-called irresistible conflict between the states had been effectively over for some time. Still, whites in the slave counties of Texas worried about the effects of Emancipation. While they had expected it to come, they had hoped for a more gradual process, and if such a sudden change in the slaves’ status must occur they questioned why its official announcement had to be made so close to harvesttime.

Across the South it was a time of social and economic upheaval. The Civil War had rent the nation, tearing North and South apart. The Confederate states were economically devastated. Yet, these same states were expected somehow to provide economic and other opportunities for the freedmen within their borders, freedmen unprepared for freedom. Clearly the states neither could nor intended to provide adequately for the former slaves, and for their part, many of the former slaves did not care to remain in the South anyhow. Theoretically, the mid- and late 1860s were the first time that they were able to move about freely. The North could not absorb all who wanted to leave the South; the West seemed large enough to accommodate all comers and it conjured up magical images in the minds of Blacks just as it did in those of whites.

So they traveled westward, doing their best to avoid the bands of white men that patrolled the country roads to drive back wandering Blacks, not to look at the bodies of murdered Negroes who were frequently found on or near the highways and roads, to escape the reign of terror that prevailed in many regions of the South. Some who made it to the Texas border managed to continue on, to the frontier areas where they acquired land or became cowboys or soldiers working for the federal government, which had assumed responsibility for frontier defense in Texas. Others stalled somewhere en route. They needed money, contracted to work on farms along the way, and after a couple of years lost the sense of idealism that would have kept them going. Or, they chose to remain in the more prosperous and more liberal population centers, taking the menial jobs that were available to them.

The newly freed slaves of eastern and southeastern Texas were even less prepared for freedom than their counterparts in the Southern states. Slaves in Arkansas, Louisiana, and Georgia, for example, had seen tangible evidence of the fight to make them free. In those areas where federal troops had moved in, the slave population had even gained some freedoms before the end of the war and had thus been given the opportunity to “try out” freedom before it was formally conveyed. Most slaves in Texas had been far removed from the war and cut off from much of its propaganda. On being informed that they were now free, many had so little comprehension of the concept that their lives remained relatively unaffected. Others misapprehended the role of the federal government, believing that if it had set them free then it would also provide for them materially. During the summer and fall of 1865 white farmers anxiously tried to contract with their former slaves as paid laborers or sharecroppers, but often with little success. A Wharton County planter named Green C. Duncan complained that “the negroes still wont [sic] hire—want to wait until Christmas.” (19) Many of the freedmen believed that at Christmas the Government would confiscate their former masters’ lands and redistribute them among the newly freed slaves.

Christmas passed, and no such steps to make economic provision for the freedmen occurred. After brief, brave forays away from the plantations, most returned to their former masters, defeated by the irony of a policy dictated by the North and resisted by the South. Eventually they entered into labor contracts with white farmers. However, during the year 1865–66 there was sufficient migration of freedmen to constitute a social and agricultural problem.

Jiles and Florence were probably not among these migrants. It is likely that they remained in the vicinity of what is now Linden, near Florence’s father and grandmother. They were in familiar surroundings and chose to remain there rather than risk the unknown. Besides, they had a small son to raise, and traveling around the country was no condition under which to raise a child. They signed on as laborers with William and Elizabeth Caves at Caves Springs, as had Susan and Milton Givins. (20)

Two other families of Black freedmen were living on the Caves property, the Crows and the Shepherds. Though theoretically free and under labor contracts with the Caveses, these three Black families, like those in other former slave counties of Texas, were hardly more than slaves. Forced to purchase their essentials from the Caveses and to give them a percentage of their crop, they were left with little to show for a year’s work.

There were certain differences between their former and present statuses, however. With Emancipation and Presidential Reconstruction in 1865, a constitutional convention had been convened in Texas. The new constitution provided for more civil rights for the freedmen than did the new constitution of any of the other former members of the Confederacy. Freedmen, though denied the franchise, were legally able to own property, enter into contracts, and seek recourse in the courts for alleged wrongs done to them. On August 20, 1866, President Johnson had declared Texas reconstructed and readmitted to the Union. But most Texans were unwilling, to accept the liberal provisions contained in the new state constitution. By the time of the President’s declaration, the constitution had already begun to be eroded by a series of “black codes” passed by the legislature. While their wording did not specifically mention the freedmen, their provisions were clearly aimed at them and at restoring the stability of the labor market. Laws regulating apprenticeships, vagrancy, and labor contracts, combined with proscriptions against intermarriage, holding public office, suffrage, serving on juries, and testifying in cases in which Blacks were not involved, effectively reduced the status of the freedmen to second-class citizenship at best.

With the passage of the harsher Congressional Reconstruction acts, the social and political status of the freedmen would change once more. The first of these acts became law on March 2, 1867, whereupon Texas was declared unreconstructed and placed under provisional government once again. A new constitutional convention was convened in 1868, the year Scott Joplin was born.

Scott, the second son of Jiles and Florence Joplin, was born on November 24 of that year, although no record of his birth has ever been found. (21) In most Southern and Western states at that time the birth of a Black infant was not considered sufficiently noteworthy to be officially recorded. During slavery, records of births and deaths of slaves, although they were not usually listed by name, were kept by slave masters, much as they recorded the acquisition or loss of other property. After Emancipation, few such records were kept. Federal censuses continued, however, and after Emancipation they included names and ages of freedmen and their families. In 1975, Charles Steger of Longview, Texas, was researching old Cass County families in Shreveport, Louisiana, municipal archives when he came upon a previously undiscovered Joplin entry. In the 1870 census, under the name of Caves were listed Jiles Joplin, Florence, Monroe, and Scott, age, 2. It is an extremely important “find,” for it is the earliest known record of Scott Joplin’s existence. (22)

Theoretically the milieu into which Scott was born was a hopeful one for Blacks in Texas, although it is unlikely that his parents were very much aware of the new laws affecting him. The 1868 constitutional convention had drawn up a new document, the Constitution of 1869, that granted more rights to Negroes, notably suffrage and an equal share in the distribution of money appropriated for public schools. But the convention had been marred by extreme factionalism between representatives from the western portions of the state, where there were few Black inhabitants, and those from the eastern sections, where there were many. In fact, some delegates from western Texas favored division of the state and creation of a new state from the areas inhabited by large numbers of Blacks. Nothing came of the proposal, and the new constitution was adopted, but it was not generally adhered to in the eastern regions of the state. While more well established than western Texas, eastern Texas was still relatively young. Disputes were frequently settled by means of arms, and the rudimentary legal system had little power. When whites were brought to trial, juries were generally very lenient, particularly when a case involved the killing or injuring of a Black. On the other hand, juries were very strict in dispensing “justice” when a Black was accused of assaulting a white. Blacks needed very little coaching on how to behave when they were around whites. After all, they’d had years of practice before Emancipation.

White backlash was considerable. In the first eight months of the year Scott was born there were 379 murders of freedmen by whites (ten of whites by Negroes) in Texas. Despite the constitutional guarantee of schooling for Blacks, in the outlying areas opposition to such schools was so great as to be almost prohibitive. (23) What few schools there were in these areas were frequently attacked; some were burned, and the teachers whipped, beaten, and otherwise persecuted. It was considered the lowest condition for a white to be a teacher of Blacks.

In the larger population centers, and in cities like Houston and Galveston, where the Freedmen’s Bureau made strong inroads, Blacks were enjoying a period of opportunity, wherein they were able to exercise their civil rights, elect Black officeholders, and enjoy some of the fruits of political influence. But for the most part the Blacks who reaped the greatest benefit during that period simply parlayed their influence while Texas was under federal supervision. For Blacks in the outlying areas, the liberal provisions of the Reconstruction constitution only made life more complicated and gave whites more reason to resent them. They dared not try to exercise their rights, for they had no Freedmen’s Bureau to support and protect them. Typical descriptions of such outlying districts from the Texas Almanac of 1867: Nacogdoches County—”Negroes work tolerably well, without a Bureau; their behavior is very good . . .”; Jasper County—”the Negroes behave very well . . . They are very contented as there have been no Freedmen’s Bureau or Federal troops, white or black, to make them otherwise.”

Back in 1865, noted Black abolitionist Frederick Douglass had optimistically declared: “Everybody has asked, ‘What shall we do with the Negro?’ I have but one answer. Do nothing with us! If the apples will not remain on the tree of their own strength, let them fall! I am not for tying them on the tree in any way. And if the Negro cannot stand on his own legs, let him fall also. All I ask is, give him a chance. If you see him on his way to school, let him alone. If you see him going to the dinner-table at a hotel, let him go! If you see him going to the ballot-box, don’t disturb him. If you see him going into a workshop, just let him alone. If you will only untie his hands and give him a chance, I think he will live. He will work as readily for himself as the white man.” (24)

But Blacks were not given the opportunity to work for themselves, nor were they let alone. After Texas was admitted to the Union for the second and last time in 1870, the Freedmen’s Bureau left the state, and Blacks were left on their own, economically weak scapegoats, symbols of what the war had cost, symbols of what white former slaveowners had lost. Like so many other Black families, the Joplins had settled into a condition of semislavery, one that differed little from slavery times except that it was in some ways less secure. They lived on and worked another man’s land in exchange for a roof over their heads and food for the growing number of mouths in the household; one year after Scott, the Joplins’ third son, Robert, was born. They were restless, looking for greater opportunity. They moved farther south, settling for a time near the town of Jefferson (25) until the chance for railroad work caused Jiles to take his family to Texarkana. (26)