2 Chapter II: Texarkana

Prior to the war there had been little serious railroad building activity in the Southwest. Most of the important cotton-producing areas were near rivers, and steamboats, which connected North and South through the great river systems, were deemed sufficient for the area’s needs. During the Mexican War, the federal government had considered supporting a southern transcontinental railway system to carry supplies to the troops stationed along the Californian and Mexican frontiers. Others, in and out of government, had begun to recognize the need for a transcontinental railway system of some sort, although there was debate over which areas the line should pass through. Stephen Douglas, chairman of the Senate Committee on Territories, suggested in Congress that the line should be built through the northern states. Jefferson Davis of Mississippi, then Secretary of War, had considered and indeed had conducted experiments with camels to solve the problems of east-west transportation through the Southwest. He suggested connecting such camel trails with a railroad system to be built from Memphis, Tennessee, or Vicksburg, Mississippi to El Paso, Texas, and through his influence legislation was passed under which builders of such a railroad would be entitled to every other section of land through which the railroad passed, providing that such land was not already owned or inhabited. At the same time, New Orleans businessmen were supporting the idea of a railroad that would extend around the Gulf through the present New Mexico and end at a point on the Pacific Coast.

While talk of such possibilities continued, some railroad companies began tentative steps toward the realization of a southern transcontinental system. In 1851 the St. Louis & Iron Mountain Railroad Company was incorporated by an act of the Missouri legislature and established to build a railroad from St. Louis to Pilot Knob, Missouri. Two years later, the Arkansas legislature approved the incorporation of the Cairo & Fulton Railroad Company, whose purpose was to construct a line from Cairo, Illinois, to Fulton, Arkansas, a town situated on the Red River near the Texas border. The Civil War and several major floods interrupted the work of these two railroad companies until 1870, when the St. Louis & Iron Mountain Railroad established and incorporated an Arkansas division for the purpose of extending the line from Pilot Knob to the Arkansas border, where it would join with the Cairo & Fulton road.

In March 1871, the Texas & Pacific Railway Company was established by an act of Congress, the only line operated under federal charter. Its purpose was to build a road from Dallas that would connect with the Cairo & Fulton road, which intended to extend its line to some major point in the Southwest. Initially, the directors of the Cairo & Fulton had planned to carry their road along the north bank of the Red River from Fulton to Shreveport, Louisiana, but the leading citizens of Shreveport objected to the planned route, fearing that it would compete with and hamper the city’s established and prosperous river transportation business. (1) Officials of the two railroads then met and decided to connect up at Nash, Texas, a town just over the Arkansas-Texas border in the extreme northeast corner of the state. This plan, too, proved unworkable, for the Cairo & Fulton was unable to obtain a charter from Texas. The officials met again and decided this time to tie up at a point due north of Shreveport amid the pine forests at the junction of the Texas and Arkansas borders. Located on a high sandy ridge ten miles west of Red River and ten miles east of Sulphur River, thirty miles north of the Louisiana line, this site was traversed by what had come to be known as the Great Southwest Trail, for hundreds of years the main trunk line of travel from the Indian villages of the Mississippi River country to those of the South and West. It was also strategically located between the city of St. Louis and the commercial centers of Louisiana. It was the area that would become, officially, Texarkana.

Probably this nebulous region was already known unofficially as Texarkana, a name invented to settle confusion, or perhaps to acknowledge the confusion, about the population center that developed there. From a basis of four families in 1864 two scattered settlements had gradually grown up at this site, one in Bowie County, Texas, and one in Lafayette (soon to be Miller) County, Arkansas.

The name Texarkana had been coined before the Civil War, although it had not necessarily been applied to this area. It was the name of a steamboat, one of the twelve that made regular runs on the Red River between Shreveport and Fulton until it sank on August 31, 1870. And according to legend, a man named Swindle, who operated a small grocery store at Red Land in Bossier Parish, Louisiana, manufactured and sold for many years a concoction called “Texarkana Bitters.” Back in 1849 a Dr. Josiah Fort had erected a sign bearing the name on his property after learning that a railroad, which owned adjoining land, had plans for the area. The most directly traceable originator of the official name, however, is Colonel Gus Knobel, a surveyor for the Cairo & Fulton Railroad.

Knobel was ordered to survey and mark the site agreed upon by the Cairo & Fulton and Texas & Pacific directors, and when he had chosen a location for the two roads to connect, he took a pine board, wrote three letters for Texas, three letters for Arkansas, and three for Louisiana and nailed it to a tree nearby. “TEX-ARK-ANA,” he is reported to have said. “This is the name of the town that is to be built here.” (2) The two railroad companies proceeded to buy up land in the area, and the first addition of Texarkana was obtained horn Eli Moores. The Carsner headright survey, which he had purchased back in 1849–50 for a wagon and a team of oxen, had long been in dispute, and when a speculator filed and paid the Carsner heirs $578 for unlocated land, Moores deeded his interest in the property to the Texas & Pacific Railway, although ownership of the land continued to be a matter of dispute. (3)

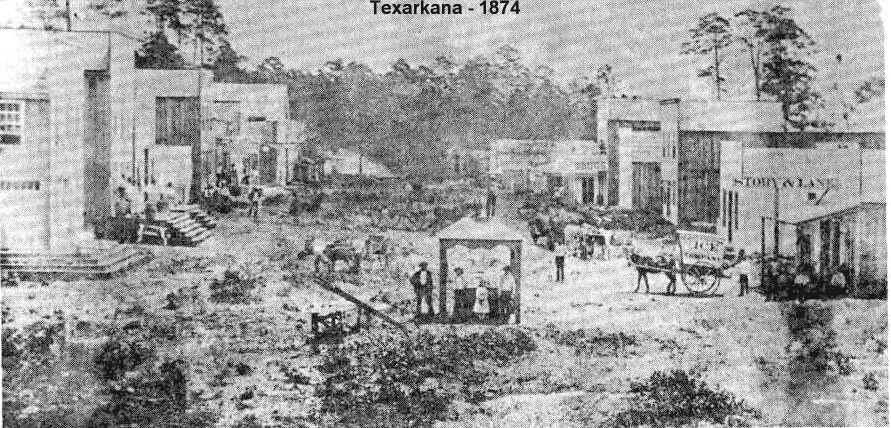

Work by the two railroads began shortly after Colonel Gus Knobel completed his survey, the Texas & Pacific laying its tracks north from Dallas via Nash and the Cairo & Fulton proceeding west from Fulton. With each thud of the mauls on the spikes, with each new section of rail that was laid, Texarkana came a bit more into being. The area experienced a large influx of people—land speculators, clever entrepreneurs, shysters, representatives of every segment of white society. Men found work with the railroads, women arrived in search of husbands or to work in the saloons and gambling houses that were hastily erected to serve the needs and take the money of the railroad men. The sound of nails being pounded into boards was ubiquitous as frame buildings were quickly erected on newly cleared sites. Blacks came, too, for there was little racial discrimination in railroad hiring practices. Although most were employed as common laborers, some were track layers, menders, brakemen, engineers, and mechanics. Jiles Joplin obtained work as a common laborer. (4)

As the standard gauge Texas & Pacific train approached Texarkana, the air for miles around was electric with excitement. The target date for completion of the Texas & Pacific tracks to the Texas border was December 7, 1873. Scott Joplin was five years old, old enough to share in the expectation and jubilation. The small town of Texarkana, Texas, stood proudly, rising up out of the lush surrounding forests. Stumps of varying heights dotted the main streets, and numerous mudholes made travel through the town an adventure for all but the most seasoned visitors. People from outlying districts began to arrive days in advance, in wagons and buggies and on horseback, and by the morning of December 7 the small town was bulging with people camped on the streets and in the surrounding forests. It was a time when the community was united in its pride and jubilation, when Blacks were almost included in the general festivities at the site where the iron horse would enter the town. Small boys ran to the tracks and put their ears to the ground, listening for the approaching train, and when the unmistakable rumbling sound could be heard men mounted their horses and galloped off to meet it. At four o’clock that afternoon the huge black engine roared into view, embers flying from its smokestack and black smoke practically obscuring its form. The train screeched to a halt. The band took up its welcoming tune, and the crowd cheered the debarking railroad officials who had come to preside over the ceremony. But the wildest applause was reserved for the train operators. Grimy-faced, wearing their cloth caps and thick cloth gloves, they were the real heroes. Not one young boy in the crowd did not want to be just like them, and they were joined in these sentiments by a considerable number of grown men.

On December 8, 1873, the day after the arrival of the Texas & Pacific train, Major H. L. Montrose, an agent of the railroad who had arrived on that train, set up business on a wide tree stump in the middle of Broad Street. Texarkana, Texas, was up for sale. The town had been divided into lots, and some forty persons were on hand to buy them, those who already lived on the lots being given first option. Among the first purchasers was Eli Moores, and soon families from Mooresville began moving to Texarkana. (5) No Blacks in the area could afford to buy these lots, which, for residential purposes sold for $200-$250. (6)

With the division of the Texas side of town into lots, a rudimentary system of streets, little more than bypaths, was established, the streets given names like Olive and Pine and Spruce and Maple in consideration of the various types of trees that abounded in the area. This practice was continued on the Arkansas side after it was divided into lots and put up for sale in January of 1874 with the arrival of the Cairo & Fulton Railroad.

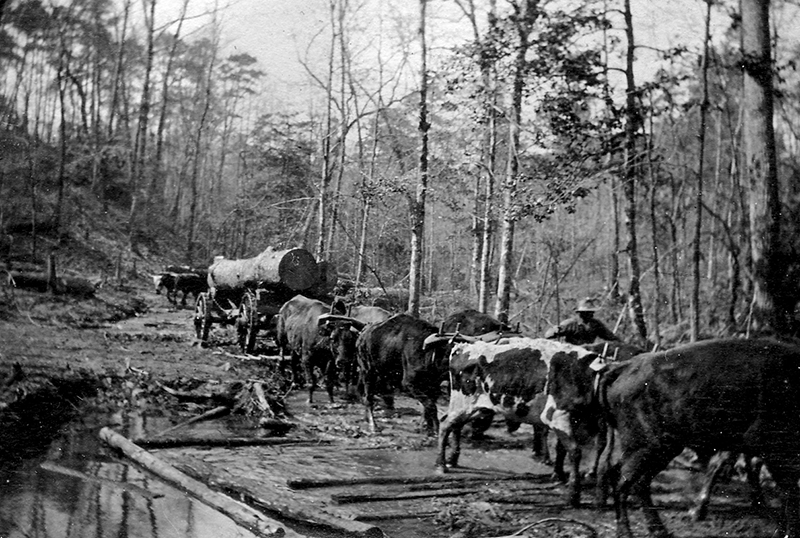

Texarkana was to see more railroad construction in ensuing years and a corresponding influx of both whites and Blacks who brought the population to 2,500 by the time the town was one year old. Initially, the Blacks tended to cluster on the Arkansas side, in an area of rolling hills called Near-Town on the northern edge of the settlement. But a small Black section developed across the state line in Texas as well, and it is here, probably on Pine Street off State Line Avenue, that Jiles Joplin rented a small frame house for his family, (7) which numbered six by 1875. (A daughter, Osie, had been born in 1870. (8)) The area was a Black “quarter” dotted with shotgun shacks rented out by white landlords, but it did not contrast starkly with the rest of Texarkana. All of the buildings were of frame construction. It was a lusty frontier town replete with saloons, gamblers, and gunmen. There was much land yet to be cleared, and wild game such as deer, wild turkey, and prairie chickens abounded in the forests a short distance away. Wagons and oxteams were almost the sole means of transportation other than horses, and a man had to be quite wealthy to own an oxteam.

For young Scott Joplin, Texarkana was an exciting place to be. The sandy hills and spring mudholes presented numerous opportunities for play, and the town was abustle with continual activity. Here land was being cleared, there new frame houses were being erected, often to replace earlier structures that had been destroyed by fire. Tinderbox-like, the town buildings frequently burned, and it was exciting to watch the townspeople form bucket brigades and pass buckets of water to throw on the fire. Perhaps, like most young boys, Scott also looked forward to being part of the bucket brigade, as his father frequently was. (9) The streets were being cleared of stumps by men who satisfied their county tax obligations in doing so. Caravans of cattle moved along the roads on their way to the railroads to the east. Wild ducks were brought in by the wagonload and sold for five cents a head; flocks of wild turkeys were driven through the streets on their way to area markets and these, too, could be purchased. And there were always new people, a constant influx of new people.

Some were freedmen, come to Texas to work on the railroads, or to Texarkana to work in the first sawmill, built around 1874. The majority of the new immigrants who arrived in or passed through Texarkana, however, were whites who had left the older Southern states of Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, and the Carolinas where there was little opportunity for them, lured by the promise of cheap land and a chance for a new start. A few were well-to-do, but according to one observer the majority were a “dense crowd of poor forlorn, wasted ill-clad people . . . They are going to Texas for new homes but with scant means.” (10)

The waves of immigrants boded ill for the situation of the Texas freedmen. Their most visible impact was political, and by the early 1870s the influence of the Republican Party in Texas had been reduced drastically. A new constitutional convention was held in 1875, and attempts to restrict Negro suffrage by levying a poll tax, though defeated, revealed the declining political influence of Black Texans and their Republican allies. Provisions for an elective judiciary and apportionment of districts caused those counties with 30 to 70 per cent Black population to be gerrymandered so as to give whites control in the election of judges.

Harder to measure but also devastating to the Texas freedmen were the anti-Black sentiments of these new immigrants. Most grudgingly acceded to the Negro’s right to personal freedom and to own property, but attempts to grant him social equality met stubborn and sometimes fierce resistance. (11) The 1870s witnessed a gradual decline in Texas legislative provisions for social equality for the freedmen. While they continued to have suffrage, there was growing sentiment in favor of restricting it in various ways. Education laws and provisions were also excellent indicators of the state’s attitudes toward Black social equality.

Although Texas ranked above the other Southern states in providing education for Blacks during the three decades following the war, it did far better in educating its white population. The whole question of education during the Reconstruction era was a complex one, for it involved a shift from a haphazard system of private schools to a system of free public education supported by tax dollars. And if there was considerable initial resistance on the part of whites to paying for the education of other (white) men’s children, then it can well be imagined how fierce was the resistance to educating the freedmen and their children.

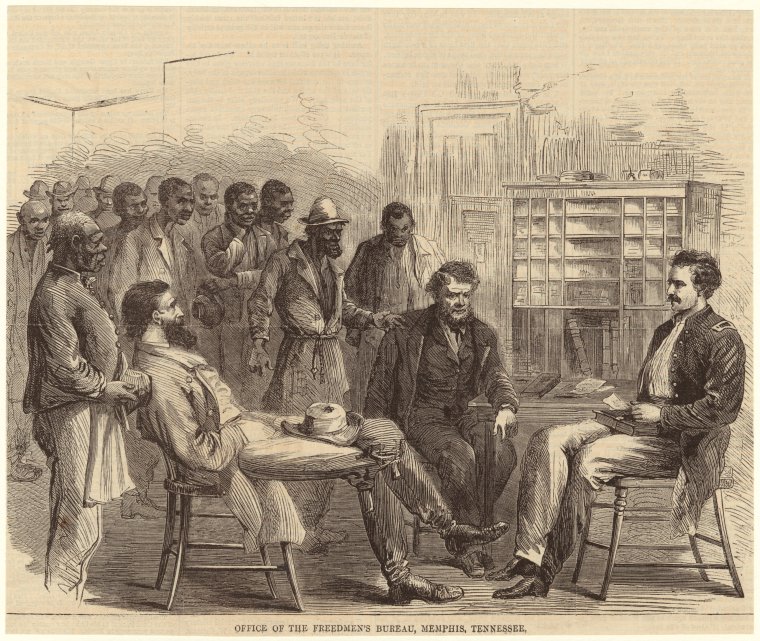

The Freedmen’s Bureau had taken the first steps toward establishing schools for Blacks during the years immediately following the war, but because of white hostility these schools were located primarily in the Houston and Galveston areas. By the time the Freedmen’s Bureau ended its work in 1870, the state had made provisions for at least a rudimentary public school system. The Constitution of 1869, framed by a Republican-dominated convention, provided for a system of public schools for all children ages six to eighteen and for compulsory attendance four months each year. However, in 1872 the Democrats gained control of the legislature and the educational provisions of the Constitution of 1869 were not enforced. In the early 1870s five Negro schools in East Texas were burned, and a number of cases of whipping and persecution of white teachers in Negro schools were reported.

In the early days of Texarkana there were no schools, either for whites or Blacks. By 1875 the formerly state-run public education system had been decentralized and a community system established, which allowed whites in many outlying areas to disregard education for their own as well as for Black children. Texarkana was one such community. But at least some of the Joplin children were being educated in a fashion, through private tutoring, for their parents were anxious that they learn to read and write. (12) Next to land, education was regarded by the freedmen as the most important ingredient of success. After the first public school system was established in Texas in 1871, Blacks were so enthusiastic that the colored schools were overflowing. When it was not possible to lease a building, Negroes offered their churches, and often put up school buildings with their own funds. (13) In Texarkana, as in other small towns, children were taught by members of the Black community who could read and write and who were paid with food by their pupils’ parents. (14)

At the same time, the Joplin children were learning about music. Both Jiles and Florence were musically inclined and talented. Jiles was a violinist and Florence played the banjo and sang. (15) Both parents encouraged musical interest in their children, for music was the life blood of Southern Blacks, the safest and most profound medium for expression of their feelings. In Black Texarkana, music was as integral a part of life as breathing. Indeed, it might be considered one reason why Black people in the 1870s were breathing at all.

Music had contributed significantly to Black survival during slavery. When the slaves were brought to the New World from Africa, a common practice among slave masters was to avert possible revolts by grouping together slaves from different tribes, speaking different dialects. In order to communicate with each other verbally, it was necessary for the slaves to learn the pidgin English their owners used when speaking to them and to speak to each other in that dialect.

For a time, they communicated with each other by means of drums which they fashioned from wood and whatever other materials were available. But when white owners discovered the slaves were using the drums to send messages from plantation to plantation, they were outlawed. The slaves then circumvented the laws by devising ways to re-create drum sounds, most notably by tapping their heels in a particular way on a wooden floor. Even after drums were allowed once more, heel-tapping and handclapping remained an integral part of plantation slave music. (16)

For centuries music was the slaves’ only effective means of communication, and the highly developed African rhythmic system allowed for considerably greater and more subtle mood variations than Western European systems. For the slave, rhythm could create as well as resolve tension, and tonal variation could encourage an individualism otherwise denied to the slaves—the individualism of the single person as well as that of the group. The nature of the slaves’ work precluded expressive use of the hands and feet, for they were engaged in rapidly moving along the rows of cotton and picking the cotton bolls or swinging pickaxes on the roads, or unloading cargo on the docks. The voice, however, was free, and the slaves sang constantly as they worked, particularly songs employing a call-mass response form.

I’m gwine to Alabamy, Oh…

For to see my manny, Ah…

She went from Ole Virginny, Oh…

And I’m her pickaninny, Ah…

She lives on the Tombigbee, Oh…

I wish I had her wid me, Ah… (17)

Each individual developed his or her own unique cry, to which the rest would respond appropriately, although there were of course some particularly talented “leaders.” Such songs helped to make the long hours of work more bearable to the slaves, and were an aid to them in tasks requiring them to work in rhythm together. Masters and overseers welcomed any device that contributed to the slaves’ work efficiency, and did not, apparently, notice that the songs were often satirical and replete with double-entendre.

Work songs, mood songs, taunt songs, chants—each form evolved to express a different feeling, but within each form resided a plethora of variations of feeling. Even simple Western songs taught to the slaves were embellished with cries and moans in a manner quite inexplicable to their white owners. Their songs were always marked by a syncopated vocal or rhythmic line. First generation slaves had difficulty mastering the Western scale, for their own musical heritage, particularly the “blue notes” or areas in the scale where tones are smeared together, interfered. Succeeding generations learned the Western scale but retained through the tradition of plantation songs the African musical forms. (18) Thus, it was possible for Jiles Joplin, when he was a slave, to play one night at his owner’s home the waltzes, schottisches and quadrilles familiar to the white guests and the next night to accompany his fellow slaves in renditions of plantation songs.

In Texarkana, Scott Joplin heard the plantation songs and felt the plantation rhythms freshly imported from the river bottom country to the east; and he heard those, altered by time and Northern influence, that his mother played on her banjo and sang. At a very early age he was able to pick out these songs on his mother’s banjo, on which he was proficient by the age of seven.

A further, and very important, influence on young Scott Joplin was the Black church, an institution still in its infancy in the former slave states were separate Black worship had been outlawed prior to the Civil War. Whites feared the slaves would use their churches as meeting places and centers of unrest, and slaves had been traditionally provided certain sections in the white churches, or separate services. One of the earliest manifestations of the slaves’ recognition of their new status as freedmen had been their withdrawal from white churches and the establishment of their own. The general reaction among whites was consternation and contempt, for Black religion was considered “woefully mixed with ignorance and superstition.” (19)

There was considerable superstition in the Black subculture, a combination of carry-overs from the African past, adaptations of white, European myths, and misconceptions of the prevailing white religions. Denied full access to organized religion and faced with an otherwise inexplicably harsh existence, the slaves had developed a rich folklore of magical and mystical elements, of superstition and conjuration. That Scott Joplin was exposed to superstition as a child is evident in his opera Treemonisha, a major theme of which is the conquering of superstition by education. To which particular superstitions he was exposed is not known, but it is likely that in the Black community of Texarkana at that time illness was attributed to being “crossed” or “hoodooed” by an enemy, graveyard dust was considered an exceptionally powerful substance, and one’s front steps were important for a variety of reasons: enemies tended to bury charms under them, so they had to be examined frequently; scrubbing them with special solutions brought good luck; washing them with urine protected the household. Borrowing or lending salt and pepper would break a friendship; sneezing in the morning foretold bad luck; a sore tongue meant a lie had been told. Few events or actions did not carry a plethora of hidden meanings. (20) Having been born free and in a northern state, Florence Joplin probably did not share many of these superstitions and instilled in her children her feeling that they helped to keep Black people in poverty and ignorance.

The boundaries between Black religion and Black superstition in those days were fuzzy. Prayers were an integral part of some hoodoos, and mystical chants were often heard in religious ceremonies. Little wonder that whites looked down on Black religion. There were few trained and educated Black ministers, and Black religion in this period was not only riddled with superstition but also charged with emotionalism.

The only Black church in Texarkana was on the Texas side, at Fourth and Elm Streets. Mt. Zion Baptist Church had been established in 1875, and it served the Black communities in both towns. (21) Like most Black churches of the period it was a frame construction with twin towers on the front, contained about thirty by sixty feet of floor space, and was financed primarily by whites interested in the moral character of the freedmen. (22) In this church, Scott learned something about religion and a lot more about sound. He sat in the room when it was unpeopled and silent, and when it served as a social gathering place, members of the congregation greeting each other and exchanging pleasantries. He saw the same room come alive with religion, rocking with shouts, singing, the clapping of hands. He learned that a song with the most mournful theme could be accompanied and its sadness intensified by a persistent, staccato clapping. And in church, as in the outside Black community, once he had apprehended the larger significance of race, he learned and understood the ways Black people had caused the white Christian religion to work for them during slavery, to use their spirituals to convey literal messages, such as this one sung when an escaped slave was being pursued by bloodhounds:

Wade in the water, wade in the water

Children, God gonna trouble the water. (23)

He learned, too, that in church as well as outside it, wherever possible his people turned a song into a dance, for the rhythm of tapping feet and moving bodies was considered essential to the expression of religious feeling. One of the most popular of these forms was the ring shout, described by an observer in 1867. ” . . . all stand up in the middle of the floor, and when the ‘sperichil’ is struck up, begin first walking and by-and-by shuffling round, one after the other, in a ring. The foot is hardly taken from the floor, and the progression is mainly due to a jerking, hitching motion which agitates the entire shouter, and soon brings out streams of perspiration. Sometimes he dances silently, sometimes as he shuffles he sings the chorus of the spiritual, and sometimes the song itself is also sung by the dancers. But more frequently a band, composed of some of the best singers and of tired shouters, stand at the side of the room to ‘base’ the others, singing the body of the song and clapping their hands together or on their knees. Song and dance alike are extremely energetic . . .” (24) Like the other children, Scott was encouraged to participate and could shout at any time. The adults, more mindful of the religious meaning of the shout, refrained unless sincerely overcome by religious fervor. (25)

The ring shouts and spirituals, the work songs and blues songs, his mother’s banjo playing, his father’s fiddling—the varied musical stimulation to which Scott Joplin was exposed as a small child is enviable. Had he been purposely taught the Western European musical forms and the rhythms and blue notes so strongly rooted in the African tradition, he would have been incapable of absorbing it all. But these forms were part of his milieu; he learned them hardly aware that he was learning. They were everywhere around him, just as they had been for the generations of Southern Black children who had gone before. But Scott showed a particular musical propensity, one that distinguished him even from his musically talented brothers and sisters. In the small Black community of Texarkana, Scott’s talent was noticed and spoken of and attracted the attention of area music teachers, who offered to instruct him.

One was Mag Washington, a Black woman who lived on Laurel Street and who later taught music at the first Black schools in the town. Another was J. C. Johnson, a small man variously remembered as a mulatto, a Mexican, “Indian looking” and partly of German descent, who engaged in an equally wide range of enterprises. He was a barber (there were no white barbers in Texarkana at the time and barbering was considered a Negro trade), a real estate trader who eventually owned more real estate than any other Black in Texarkana, a musician, and a music teacher. His home on Wood Street was only three or four blocks away from the Joplin residence, and there, in his neat small house, he would give music lessons on the piano, violin, and horn, (26) the strains wafting over his fan-shaped wooden gate and out into the neighborhood. Because he was a musician and music teacher he enjoyed the title Professor and was addressed in this manner by both Blacks and whites. (27) Johnson played in the classical style. “He was a kind of church man,” recalls elderly Texarkana resident George Mosley. “He didn’t play much ragtime (later), and I don’t think he played at dances. A lot of people had guitars or fiddles, but his music was not like most.” (28) From these early music teachers, Scott Joplin learned to read music and gained a better knowledge of Western European musical forms, and because he was talented they taught him for little or no fee.

When he was not practicing his music, or being tutored in academic subjects in the neighborhood, Scott did what the other boys in the neighborhood did. He frequently ran errands, getting lunch for a laborer or water on a hot afternoon. He helped feed the chickens and pigs that most people kept in their yards, and when a flock of wild turkeys was driven through the town, he was often sent to purchase hens for people in the neighborhood. He played stickball in the street and dug in the ubiquitous sand and helped take care of his younger brothers and sisters. In the late spring of 1880, an epidemic of measles spread through the Black section, infecting most of the young children. While ten-year-old Osie had primary responsibility for caring for the younger children, Will, four, and Myrtle, who had been born in March (29), she, too, had contracted measles, (30) and at such times Scott and Robert took on the responsibility. Perhaps the crisis was welcome in some ways, for it helped take their minds off their parents and their problems. Jiles and Florence were not getting along. It is said that they argued over Scott. Jiles felt that Florence overencouraged their son’s interest in music. Music was a fine pastime but certainly not a suitable vocation. Few Black men he knew could make a respectable living at it. Scott’s nephew, Fred Joplin, recalls that this attitude prevailed when he was young and dreamed of being like his uncle. “We don’t want no piano player,” his family said. (31) But it is unlikely that the disagreement over Scott was the cause of their separation, as legend would have it. Whatever the reasons, Jiles left Florence and the children in the latter half of 1880 or the early part of 1881, when Scott was twelve or thirteen years old. (32) He moved to a boardinghouse on Laurel Street on the Arkansas side and entered into another marriage-like relationship with a woman named Laura. But he maintained close contact with the family.

By the time Jiles left his family, Texarkana had progressed substantially. Jay Gould passed through the town in March of 1880. “Texarkana will grow,” he informed Mayor Beidlee. The town had an opera house and brick buildings, a newspaper, and many stump-free streets. A month after Gould’s visit, it had its first Bath Rooms, installed in the rear of the white-managed City Barber Shop. Hot Baths were 25¢, Cold 20¢, Salt 25¢, Sulphur 50¢. Blacks enjoyed some freedoms. In the year 1881–82, half the men who served on juries were Black. But neither material nor social progress affected Florence Joplin to any great extent. Left with the responsibility of five children aged twelve down to infancy (Monroe had a job as a cook and had moved out before Jiles left), she concentrated on providing for them. While she had earned money previously by taking in washing and ironing, (33) it was not enough to support her family.

Probably to find less expensive living quarters, she moved her family over to the larger Black section on the Arkansas side of Texarkana, to the area called Near-Town and to a house at 618 Hazel Street on the corner of Sixth. (34) The area was one of sand flats, the sand so deep that you bogged down in it when you walked; and as it was at the foot of a hill extending downward from the east, it flooded every time there were heavy rains. In the late spring it was a veritable mud flat. (35) The house at 618 Hazel was on the edge of the Black section, in a neighborhood that was quite racially integrated. While Blacks lived on the even-numbered side of the street, mostly whites lived on the odd-numbered side. (36)

At about the same time Florence and her young children moved, the infant and still informally organized Canaan Baptist Church also moved from Mrs. Samuels’ parlor on Eighth Street to the recently evacuated Dyckman Hide house on Ash and East Ninth Street. It was not a church building per se, but it was large and roomy and far better suited to the needs of the congregation than Mrs. Samuels’ parlor. The members made simple board benches and fashioned a makeshift pulpit and looked forward to the time when, new members having been attracted by the existence of a separate building in which to worship, Canaan would be officially recognized and organized by Mt. Zion. (37) Florence Joplin became caretaker of the church. (38)

Florence also worked as a domestic for white families in the area, among them the Cooks on Hazel Street. The Cooks owned a piano, and Florence realized here was an opportunity for Scott to practice on the instrument. She requested and received Mrs. Cook’s consent to take Scott along when she went there to clean. (39) While his mother dusted and mopped around him, young Scott sat on the high bench of the Cooks’ upright in the parlor and practiced the scales his teachers had taught him. As he grew bolder, he began to try his hand at playing the sheet music the Cooks had—sentimental ballads by Stephen Foster, perhaps, minstrel tunes, folios of European piano music, and undoubtedly a march by John Philip Sousa, whose music was becoming immensely popular all over the country. And as he grew bolder still, perhaps he experimented with tunes of his own. He was blessed with two characteristics important to a composer/musician. He had perfect pitch. If a chord were struck on a piano in the next room, Scott could walk into the room and duplicate the chord exactly. (40) He also had the ability to remember tunes and fragments of tunes that he had heard years before. Already he was taking those remembered tunes and incorporating them, with elements of his own, into original compositions.

Scott was probably a teenager before he was able to go to an actual school building for Black students. Although a relatively good public school system had been established in Texarkana for white students, a school for Black children came only later. (41) Located in a frame building on Seventh Street and the Kansas City Southern tracks on the Texas side about ten blocks from Scott’s home, the school was called Central High School, although the “high” part was purely honorary. There would be no upper grades for some years. Later, a small brick building was erected to house the school. Consisting of one above-ground story and a basement, it was typical of the accommodations for Black students at the time. Below street level, the building’s grounds and basement were frequently flooded after heavy rains, necessitating rescue operations by parents. Fill was then added to bring the school grounds up to street level and the drainage canal was levied to check flooding. Another, more spacious building was erected. Students were placed in grades according to their age rather than their educational level, a practice that continued until a centralized state public school system was firmly established, (42) and thus if Scott attended Central High he was probably placed in seventh or eighth grade. There were no extracurricular activities, (48) but in this era so soon after Emancipation parents were eager for proof that their children were indeed securing the magic key called education, and there were numerous assemblies and programs to assure them. If Scott Joplin attended the school, it is likely that he was a sort of musician-in-residence and served as musical accompanist at assemblies, whether indoor activities or outdoor programs such as the annual plaiting of the Maypole. (44) Whether or not Joplin attended the later Orr School will be discussed shortly.

Despite her poor economic circumstances and difficulty in supporting her family, Florence Joplin purchased a piano, primarily for Scott’s use. (46) While this was an extravagance for a poor family, it was not an uncommon one. Music was the chief entertainment in that era, and even some of the poorest homes boasted a piano, usually secondhand. Probably the one Florence purchased was a used model and an old square-type piano

in which the strings were parallel to the keys as in the clavichord. Sheet music could be purchased at the Beasley Music Store for five cents and ten cents, and Scott began spending most of the money he earned doing errands and odd jobs in the neighborhood to buy the popular sheet music of the day. Florence Joplin considered her purchase a worthwhile investment, for she had little doubt that her second son was destined for a musical career. Already he was well known in the Texarkana area, and in this era when Black people grasped with clawing fingers at whatever renown they might enjoy, talent like his was to be encouraged.

There were many opportunities for a young Black musician to perform in an East Texas town in those days. Most Blacks were poor and their lives monotonous, a situation that became more severe with increasing political repression. Correspondingly, the freedmen sought greater solidarity among themselves and more social diversions. The Black church became increasingly the center of Black social as well as religious life. In the cities, Blacks organized fire companies, benevolent societies, fraternal societies (The Grand United Order of Odd Fellows for Negroes was organized in Texas before 1879). Several lodge halls were located in Texarkana’s sand flat. Lodge meetings would be held until about 10 P.M., whereupon the hall would be turned over to the young people for dancing. The music was similar to that played at dances for whites—polkas, schottisches, waltzes, and two-steps. (46) Baseball teams, literary, dramatic, and debating societies—every town of any size had its diversions. On weekends Blacks from outlying areas arrived to purchase supplies and enjoy the company of other Blacks. The towns were sites of numerous festivities throughout the year. The most important were Emancipation Day and Fourth of July, but there were also celebrations at the end of the harvest season and the close of the school year, railroad excursions, and school and church picnics.

Scott Joplin performed at church socials and school functions, later for Black clubs. “He was smart,” Zenobia Campbell, now deceased, recalled, “especially in music. . . He did not have to play anybody else’s music. He made up his own, and it was beautiful; he just got his music out of the air.” (47)

Still later, he played at area dance halls, including that of Webster Crow, a dance teacher, and one on Law Street. All the while, he was listening to and absorbing into his own idiom the marches, the popularizations of the musical forms of the Black church, the minstrel songs and semblances of the blues that were sung and played by other area entertainers. He also probably heard the currently popular tunes played in syncopated style, most notably those of composer Louis Moreau Gottschalk, whose composition The Banjo contained clever banjo imitations and was very popular at the time. Alexander Ford felt sure he had heard Scott play the music found in “Maple Leaf Rag” in Texarkana before he began playing in the larger cities. “Scott worked on his music all the time. He was a musical genius. He didn’t need a piece of music to go by. He played his own music without anything.” (48)

Scott was a small young man of medium-dark complexion who looked remarkably like his father but who had far more ambition than the older man. He yearned to make a living in music and to escape the conditions under which Blacks in East Texas lived. Black boys his age had few opportunities in the Texarkana area. The only employment open to them was railroad work, jobs in the lumber camps and sawmills, or domestic and personal services. Scott’s older brother, Monroe, had gotten a job with a railroad. “He would ride as far as Marshall, and stay there two or three days; then he would come in and take the very next train out to Marshall,” according to Alexander Ford. As a porter, he could pass through any area of the train, but had he attempted to ride as a passenger he would have been confined to the “Colored” section. In the lumber camps and sawmills, Blacks were as signed the most menial and distasteful jobs, and had no hope for promotion or increased responsibility. Scott had no liking for manual labor. He was also a proud young man who did not wish to spend his life serving whites. He admired his music teacher, J. C. Johnson, and emulated him in some ways—in his quiet pride, in his liking for soft and gentle tunes, in his awareness of the importance of education. But J. C. Johnson was an excellent businessman. His real estate investments had already made him one of the wealthiest Blacks in Texarkana. Scott, on the other hand, had little head for business and less interest in it. Besides, he did not wish to spend the rest of his life in Texarkana. The excitement he must have felt as a small boy about the coming of the railroad and the end less possibilities for travel that it represented had remained with him and matured into a desire to see what was at the other end of the line. And thus, while other boys his age played and partied, aware that there was no future and that the present was all, Scott Joplin kept to himself and practiced his music. “Scott was earnest,” Zenobia Campbell remembered. “When a bunch of boys got together on a spree one night and asked Scott to go with them, he said, ‘No sir, I won’t have anything to do with such foolishness. I’m going to make a man out of myself.'” (40)

For this reason, among others, it is probable that Scott attended school longer than most boys his age. The theme of Treemonisha and Joplin legend both indicate that his mother and later Joplin himself believed deeply in the importance of education. Also, there is evidence that Joplin was fairly well educated. He later enrolled in the music school in Sedalia, read such books as Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, wrote well enough to have a brief statement published in a New York newspaper. At least one Joplin family friend claimed to remember Joplin’s attending Orr School, located on the corner of Ninth and Laurel on the Arkansas side of town.

It was organized in 1886 and established in 1887, when Scott was eighteen or nineteen years old. But Zenobia Campbell recalled, “It was in the old two-story building. The little kids like me went downstairs, but the big high school kids went upstairs. Scott was in high school upstairs when I was little and went downstairs.” (50) Although Scott would have been one of the oldest in the school, there would have been little stigma involved. He was something of a celebrity within the Black community, a serious and intense young man about whom older Blacks nodded and assured each other that he would go far.

Scott was also known in the white community and in the surrounding towns. When he was about sixteen, he had formed a vocal group, the Texas Medley Quartette, with his brother Will and two neighborhood boys, Wesley Kirby and Tom Clark. After their first engagement in Clarksville, Texas, about eighty miles west of Texarkana, they secured engagements elsewhere and, though they retained their original name, took on a fifth member, Robert Joplin. The group played in and around the area for some four years, and the money they earned was welcome in the Joplin household. (51) But Scott Joplin had bigger plans, and around 1898, when he was twenty, he left Texarkana to seek his musical fortune. (52)