3 Chapter III: Itinerant Pianist

At that time a throng of itinerant pianists crisscrossed the South and the Midwest by train and river steamer, by wagon and on foot, performing wherever they could and for whatever they could get. They were in great demand in those days, when sources of musical entertainment were few and the arrival of a traveling performer or minstrel show was a notable event in a small town. Up and down the Mississippi River they traveled, and over into Kansas and Missouri, Oklahoma and Nebraska and Texas, in a time when these areas were in a constant state of flux. Hundreds of people were traveling westward in railroad cars, covered wagons, buggies, buckboards, on horseback and muleback. A few even rode big, high-wheeled bicycles. There was a fever in the country—a fever for cheap farmland and the independence that land ownership could offer to these mostly poor travelers. The Government was opening up former Indian territory for settlement, and people from older states were heading westward searching for new opportunity. (1)

Enterprising businessmen established trading posts and general stores to serve the needs of these travelers. Traveling salesmen and hucksters schemed to relieve them of their small savings. Itinerant entertainers were everywhere. They rode the paddle-wheelers up and down the rivers and stopped at riverbank taverns. They barnstormed with small minstrel and variety shows and accompanied medicine men, attracting a crowd with their music before the "Doctor" or "Professor" appeared to convince his audience how sorely they needed his homemade elixir. They accompanied tent shows to the small towns and frequented the saloons and honky-tonks in the large population centers, and over the years they formed a musical subculture.

They represented a variety of geographical and musical backgrounds. Some had been trained in European musical forms; some had not. Some could read music; others could not. They were from the South, the West, the Midwest, and the North, and as they affected the area around the Mississippi Valley, so that area affected them. They learned the folk songs and dances of the people for whom they played, added to them their own folk songs and dances, their hymns, and included, too, the marches, dances, and tunes from popular sheet music to produce an amalgamation of assorted forms and themes which over the years had taken on a rather distinct form, an extended melodic line of syncopations in conjunction with a regularly metered bass.

Neither they nor their music was socially acceptable. They existed on the fringes—of towns, of society—and yet it was this very semi-outcast status that gave them a sense of belonging to each other. They shared a love of music, of travel, of new experiences—a commonality that overshadowed whatever differences separated them. They ranged from little more than adolescents to old-timers in their sixties and seventies. They were mostly Black, but by the late 1880s there were also a considerable number of whites.

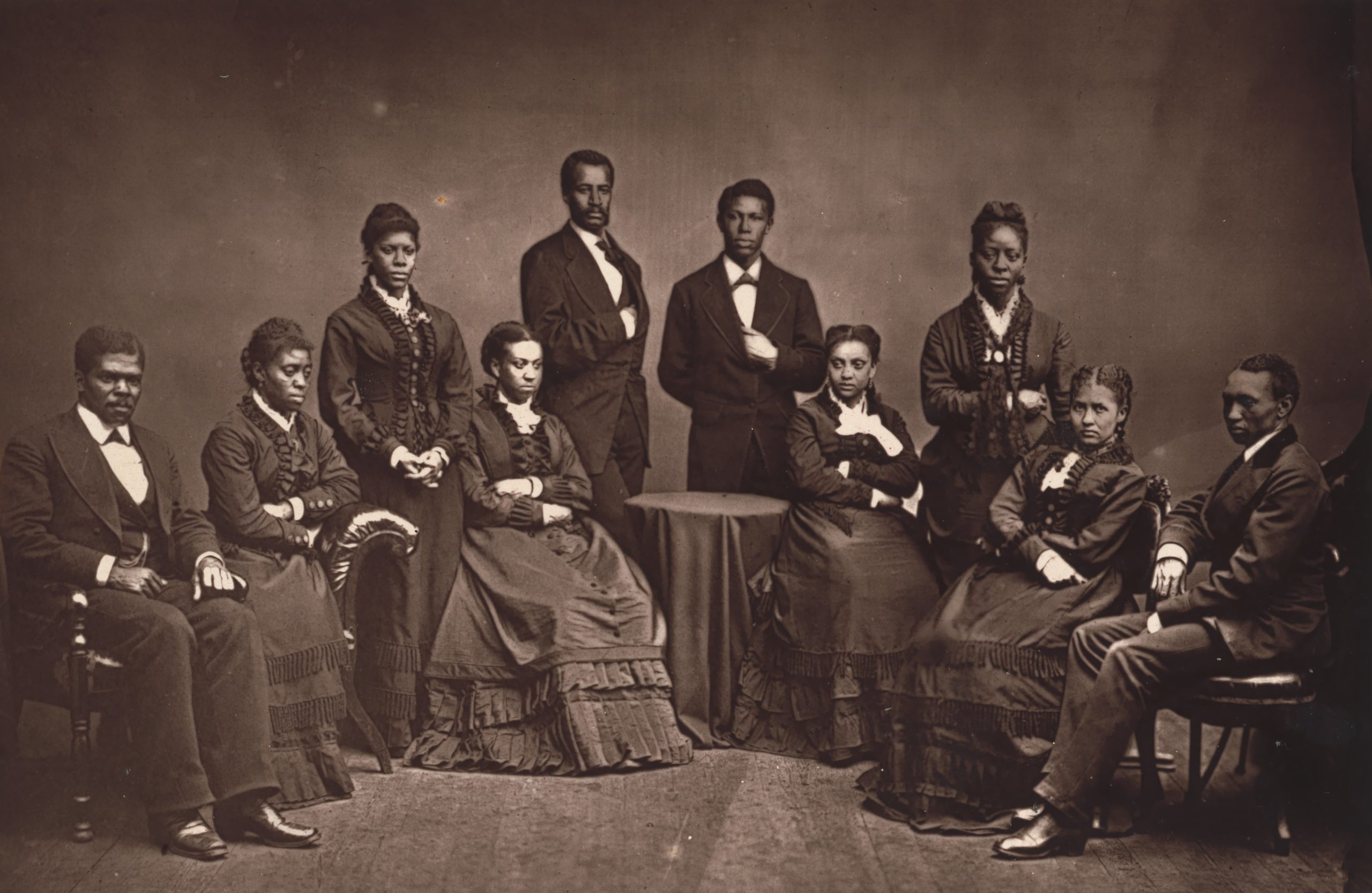

The two groups of itinerants, the whites and Blacks, existed sometimes separately, sometimes together, within the same milieu. Rather like a double helix, they separated, then came together, then separated again according to the social and geographical environment through which they happened to be traveling. Often their paths paralleled each other, as did the social lives of their respective audiences. Both lower-class Blacks and lower class whites engaged in similar yet separate socializing. Both had their fairs and their excursions, their dances and lodge outings. In the towns, Saturday was the day when people from the countryside would come to do their shopping or selling and then linger on into the evening to attend a dance or patronize a local drinking or gambling establishment in the white or Black section of town according to their own racial heritage. The traveling musicians, appearing singly or in groups of two or three, were essential to all these activities, whether among the poorer classes of Blacks or the poorer classes of whites. The better classes of both races, the straitlaced, conservative, churchgoing pillars of their respective communities, had their own bands and string orchestras, and had little use for the musical drifters. Only Negro groups like the Fisk (University) Jubilee Singers, who began touring in 1871 and were highly successful, gained entree to the better classes of Black and white society.

In the larger towns the white and Black itinerants came together. The well-established red-light districts in these towns sported a minimum of segregation. White or Black, a talented musician was a talented musician, a charming madam was a charming madam, and a man with money to spend was a welcome sight. Blacks and whites in these districts were all outcasts of one sort or another, and racism seemed rather beside the point.

Life was never monotonous for the traveling musician. Arriving in a small town, he was likely to set up on a sidewalk corner and play for coins tossed at his feet, until he was hired to play for a picnic or a railroad or steamboat excursion. Hearing of a fair or a race in some other town, he would set out for it, walking or riding the train or steamboat depending on his financial circumstances at the moment. On the way, he might meet up with a medicine show whose owner was looking for a musical pitchman, and find himself traveling in a direction quite different from the one on which he had set out that morning. Nearing one of the larger towns, he might leave the show to spend a few weeks in an established red-light district. He lived from day to day and from hand to mouth. At times, he would play almost continuously for three days or more and have money for a woman, for a keg of beer and a bag full of food. At other times, he would be so broke he would have to play for his supper or sleep in a corncrib. If he was near a larger town or city, he would try to sell a quick song or tune to a local music publisher. It might not be entirely his composition, but then the music of the itinerant musician in those days was an amalgam of influences and styles, of melodies heard in the fields and songs picked up on the levees and phrases picked out on barroom pianos. Every itinerant in those days was a composer in a sense, and the traveling musicians, white and Black, sharing their ideas with each other, learning from one another, also shared the musical idiom that had already become known as ragtime, for music played in "ragged time." (2)

The term ragged time is a colloquialism for syncopation, the placing of emphasis in the melodic line where it would not be expected to fall in a "straight" rendering of a piece, and it was the syncopation of the music that had the greatest impact on the unschooled white listener in the late 1880s. Even though syncopation is not the defining element of ragtime, it differed so radically from European rhythms and the popular arrangements of folk tunes that it must have been positively shocking. Yet to us nearly a century later, a period of decades that has seen the development of jazz and rock music, the syncopation of ragtime seems quite tame. Indeed, even then it was far tamer than that of the forms out of which it grew, most notably the staccato clapping that often accompanied songs sung in Negro churches and the foot-produced drum sounds of plantation dances. (3)

The term ragtime was not then nor is it today a particularly appropriate label, being far too simplistic in definition. But there is no one-word definition that adequately defines the form. Ragtime is essentially a collection and integration of little melodies, played in a manner similar to the way in which Black plantation and church songs were sung and Black plantation dances were performed, all of which forms included syncopation but were not determined by it. There is also no smooth developmental line on which one can pinpoint the emergence of ragtime—no single predecessor or successor in the evolution of distinctly American music. It represents an amalgamation of forms and trends. The one identifiable pattern it follows is that it conforms to the custom in American music of interracial influence. Whites adapt Black forms which are in turn adapted and parodied by Blacks, which are once again adapted and parodied by whites, not always with the most sympathetic intentions.

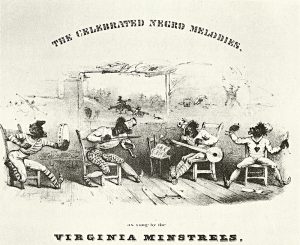

Minstrelsy represents an excellent example of this process, and ragtime owes much to the minstrel tradition. The roots of minstrelsy lie in the plantation slave quarters, which inevitably had a talented individual or band that could sing and dance to the accompaniment of the banjo, the tambourine, and the "bones" (ribs of a sheep or other small animal) and tell jokes.

These individuals and bands frequently entertained for their masters and fellow slaves, and some became semiprofessional, although their travel was circumscribed during the slavery period. At the same time, white entertainers were traveling wider and whiter circuits, but inevitably they came into contact with the Negro groups. Negro mannerisms and customs being inherently funny to whites, the white entertainers began to adapt them for comic appeal. As early as 1810, blackface impersonations were being presented by what can best be described as circus clown-type performers, although the modern circus had not as yet been organized. By the next decade, solo blackface acts with the traditional slave instruments had become popular. The use of these percussive instruments, the banjo, tambourine, and bones, helped to establish the rhythmic foundation of later minstrel shows. (4)

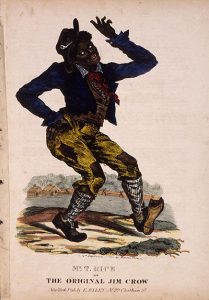

Minstrelsy in the form with which we are most familiar began around 1828–29 when, according to legend, an actor named Thomas Rice included in his act the song and dance of an old Black man who worked in the stable next to the Louisville theater where Rice was appearing. Edmon S. Connor, who claimed to have been an eyewitness to this birth of minstrelsy, recalled:

As was then usual with slaves, they called themselves after their owner, so that old Daddy had assumed the name of Jim Crow. He was very much deformed, the right shoulder being drawn up high, the left leg stiff and crooked at the knee, giving him a painful, but at the same time laughable limp. He used to croon a queer old tune with words of his own, and at the end of each verse would give a little jump, and when he came down he set his "heel a-rockin'." He called it "jumping Jim Crow." The words of the refrain were:

"Wheel about, turn about,

Do jis so,

An' ebry time I wheel about,

I jump Jim Crow!" (5)

Intrigued and amused, Rice adapted the character of Jim Crow for his act, using not only the old man's song and his funny little dance but also his name. Thomas Rice became known professionally as Daddy 'Jim Crow' Rice. "Jump Jim Crow" was an immediate hit, in the United States as well as in Europe, and Rice's act spawned a host of imitations, (6) almost exclusively white actors in blackface. Parodies of Negro songs became popular sellers in sheet music. Stephen Foster was perhaps the most successful composer in this genre. By the middle of the century troupes of white entertainers were traveling the circuits presenting blackface performances that included music, dancing, and jokes, the full minstrel show that was the precursor of vaudeville.

Minstrelsy enjoyed its Golden Age from about 1850 to 1875. During that time, though the minstrels' material consisted of adaptations and parodies of Negro music and mannerisms, they adapted it creatively and with some sympathy. There was in these imitations a certain sense of poignancy and romanticism about the slave and his life (although this hardly benefited the slave, since it glorified the slave regime) and a freshness that would be lost in the post-Civil War period.

By about 1875 minstrelsy had lost its creative spark. Since Emancipation, Black entertainers had enjoyed more freedom of movement and been allowed onto the minstrel circuits, but minstrelsy had become so formularized by that time that even the Black minstrels performed in blackface. The wit, imagination, and brightness of early minstrelsy had degenerated into a standard routine of not particularly funny jokes, wooden dancing, and undistinguished songs, and while the emphasis on so-called Negro characteristics, mannerisms, and speech idioms was stronger than ever, there were no longer clever adaptations but unimaginative parodies. Perhaps partly in an effort to enliven the form, and partly in response to the social upheaval caused by Emancipation and the Reconstruction period, minstrelsy became harsher in its Negro characterizations, and it was this period that fixed in the white American mind the unfortunate stereotype of the Negro as happy-go-lucky, dancing, shuffling, irresponsible, etcetera. (7)

While the minstrel shows were variety presentations and not primarily associated with musical performance, they affected the itinerant musicians. Lay audiences, accustomed to the style of minstrelsy, often demanded it of the musicians who played for them, a confining and frustrating position for the musicians exposed to a wealth of musical styles and creative possibilities. And for the Black itinerant musician the minstrel-engendered Black stereotypes were a difficult cross to bear. For a serious young man like Scott Joplin, they must have provided some impetus to present Negro musical idioms with the dignity and understanding they deserved. By the mid-1890s Blacks would infuse minstrelsy with a new creativity. In the middle and late 1880s itinerant Black musicians had already begun this rescue process, by adapting elements of rhythm and swing in minstrelsy to the ragtime form.

Ragtime can also be related to Negro songs and Negro influenced songs—not to their words or tunes but to their form. Traditional slave songs were fluid in form, or open-ended, for their purpose was to communicate the feelings of the moment. The call-mass response form of work songs and many spirituals depended greatly on the effectiveness of the leader, the inflection of whose call would produce a corresponding inflection in each chorus. (8) Calls and choruses related in subject matter to one theme, but potential variations were endless, and the more effective the leader the more varied but related the verses.

Jordan River, I'm bound to go,

Bound to go, bound to go, —

Jordan River, I'm bound to go,

And bid 'em fare ye well.

My Brudder Robert, I'm bound to go,

Bound to go, etc.

My Sister Lucy, I'm bound to go,

Bound to go, etc. (9)

White minstrels had adapted the Negro song form but introduced theme combinations that Blacks would never have used. The following is obviously a gross parody of a Black spiritual:

Monkey dressed in soldier clothes

All cross over Jordan

Went in de woods to drill some crows

O Jerusalem— (10)

Yet the call-mass response form was maintained, introduced to, and accepted by the general audience, and later appeared in ragtime. In rag the composer/performer essentially plays the part of both leader and chorus, his effectiveness dependent upon his skill at inflecting the various choruses. In plantation songs, each chorus is unique in the manner in which it introduces and develops the theme and relates to the other choruses. (11) Rag, too, is open-ended and was particularly so in this early period of ragtime, before the music was actually written down. Effectiveness of communication was more important than structural perfection.

Musicologist Addison W. Reed has suggested a further relationship between Black vocal forms and ragtime. "One may notice particularly the melodic rise at the end of a spiritual which automatically lets one know that we have or are approaching the end, the same may be said for the 'ride-out' (grandiose ending) of a rag. And the changing character of a holler or work song may be compared to the rhetoric of each chorus of a classic rag . . . It may be argued that the very nature of the introductions, closing sections, bridges and codettas (of a rag) relate to the vocal forms of the Negro . . . Just as the introduction to a rag denotes the mood, the same can be said for the leader of a spiritual. As the closing sections and codettas add an additional phrase which compliments the preceding chorus, so did the leader in his emphasis of what the congregation had previously sung. The same may be said of bridges since they provide a link between two related passages, as did the leader and so was the function of the call in relation to the response." (12)

Work songs and hollers, spirituals and blues, the percussive rhythms of the banjo and bones—all contributed in some way to the development of ragtime. But the most important basis of ragtime is dance music—particularly Black dance music. In some ways, it was the character of the life of the itinerant pianist that led to the development of ragtime. The wine rooms and saloons, the cafes and bawdyhouses where they played were often transient, fly-by-night affairs, known neither for their permanence nor their opulence. Entertainment "budgets" in these places were small, the chief investment being a single piano. Musicians who played other instruments of course furnished their own, but rarely was anything more than a small combo provided. The chief entertainment was the lone pianist, who worked not for a guaranteed salary but for whatever tips he could get. In return, he was called upon to provide a variety of musical entertainment—background music, music to sing by, and especially dance music. Over in respectable society, a dance band would be available. In the red-light districts, the piano was all, and the most popular and successful musicians were those whose music made their listeners want to dance, want to tap their feet and move their bodies to its rhythms.

Naturally, this music also had to conform to the types of dances that the audience wanted to do and that were in vogue. The popularity of marches, most notably those by John Philip Sousa, had spawned the two-step. In fact, that dance became identified with a Sousa march, the Washington Post March, so thoroughly that it was often called The Washington Post. (18)

Blacks, as was their custom and their irresistible impulse, had subsequently adapted and amended the two-step and created the "cakewalk." Originating in the South around 1880, its primary characteristic was promenading in an exaggeratedly dignified manner. Contests were held among Blacks for which the prize was usually a cake, giving rise to the expression "That takes the cake." By the mid-90s, whites had in turn adopted the cakewalk and white composers would make a fortune selling cakewalk sheet music. More fluid and imaginative than the established two-step, the cakewalk was nevertheless a regularized form, one that allowed for more improvisational possibilities than its precursors but that would be considered highly formalized compared to later dance styles such as the Charleston, Black Bottom and Lindy Hop.

Black folk dances were also popular in evolved form. Originating in the United States in plantation slave quarters (and undoubtedly containing elements of African tribal dances, although this is difficult to document), these dances were first brought to the attention of the larger white public via the white minstrel shows and were then reprocessed through the Black imagination to be accepted first by the low-class segments of white society and eventually by all classes. Ragtime incorporated all these dance traditions, and dancing was its primary impulse. A piano rag was like a keyboard dance suite intended to inspire and accompany expressive physical motion. (14)

Just when and by whom the first piano rag phrase was played will never be known, for this was a time when music went unrecorded except in the ears and minds of its listeners. It is likely that certain rag elements were present in the playing of itinerant pianists many years before the ragtime style seemed to coalesce and become a recognizable form in the 1890s. In 1892, Tony Jackson, a New Orleans Negro pianist, composed a tune called "Michigan Waters" that contained some elements that could be classified as ragtime, and the next year, 1893, the word "ragtime" appeared for the first time on a sheet music cover—Fred Stone, a Negro musician in Detroit, published "Ma Ragtime Baby." It will be remembered also that an old-timer in Texarkana believed that he had heard parts of "Maple Leaf Rag" even before Joplin left the town to strike out on his own.

Scott Joplin joined the ranks of the itinerant musicians who moved across the South and West developing the music that would become ragtime. It is not known where he went or how long he roamed. It is likely that he caught the excitement of the frontier West, the rush for land, the influx of people from more established sections of the country. He probably encountered the Indians who traveled some forty thousand strong to Arkansas City from Indian Territory every three months to receive their government allotments, paid to them through the First National Bank of Arkansas City. By day they traveled, most of them walking, wrapped in blankets; at night they set up their camps along the riverbanks. (15) In another era, they might have presented quite a spectacle, but in those days they were simply a part of the phenomenon that was the frontier West.

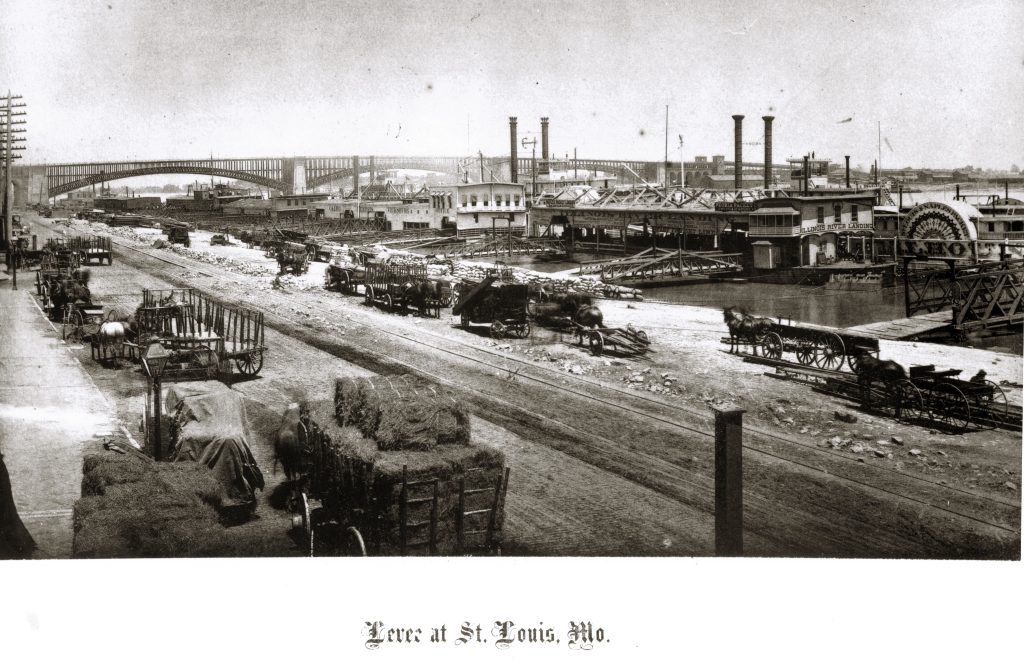

Eventually, Joplin made his way to Missouri, where he settled for a time in St. Louis, probably about 1890. A large, sprawling city known as the "Gateway to the West," in its variety and bustle St. Louis resembled a seaport, although it was far from the sea. The major population center of the Midwest, it fronted on the Mississippi and thus had naturally become one of the chief commercial centers for the river traffic from and to the South. Railroads had joined the river byways, and by the time of Joplin's arrival the city had become the Midwestern center for rail as well as riverboat travel.

By 1900, Blacks in St. Louis would number 35,516, or 6.17 per cent of the population. They were concentrated within two of the city's ten wards, but within these wards there was considerable residential and social variety. The higher class boasted its own social and literary clubs and church-sponsored entertainment, its own brilliantly uniformed bands, and its own lodges and fraternal organizations. Still, members of this class were rarely seen at a downtown theater or even at one of the summer gardens, resorts which were popular among all classes of white society. The mass of St. Louis Blacks had their railroad and steamboat excursions, barbecues, cakewalks, picnics and church sociables, once again, entirely segregated affairs. And then there were the low-class Blacks, among them the operators of saloons, who were probably financially better off than some of the upper-class Blacks. By 1901, St. Louis Blacks would own eleven saloons, representing a capital investment of $ 17,000, employing a total of forty-eight people. Wrote a white observer at the time: "The saloons are perhaps the most profitable enterprises engaged in. One has been established since 1879 and has $5,000 invested in it . . . The color line seems not to be drawn among their clientele, but the white customers are, of course, of the lowest class." (16)

About half of these Black-owned and operated saloons were located in the city's sporting district, a section not far from the waterfront and near the Union Railroad Station, whose main thoroughfares were Chestnut and Market Streets. A rather large section, as befits a city that called itself the "Gateway to the West," it boasted numerous saloons, cafes, cheap boardinghouses and brothels, among the most colorful of which was Babe Connors' place. According to S. Brunson Campbell, the most beautiful and elegant Black women were to be had there, and their pimps, or "Macks," were equally glamorous. Supported in style by their women, they dressed in silks and diamonds, sported jewelry made from twenty-dollar gold pieces, and spent most of their time showing off their finery and checking up on their women. Ragtime was the music played at Babe Connors' place, and Campbell recalled that Scott Joplin's compositions would be heard there before they were set down on paper. (17)

As in every red-light district, there were certain establishments in Chestnut Valley that the musicians frequented, although they might be performing elsewhere. One of the newest and most popular of these was the Silver Dollar Saloon at 425 South Twelfth Street, owned and operated by Black "Honest John" Turpin, a pianist himself and a former laborer who had opened his saloon in 1890 with his three sons, Robert, Charles, and Thomas. (18) Here at almost any hour of the day or night St. Louis's piano players could be found, waiting for a messenger from some other establishment to come looking for a musician, playing for one another, and talking about music. Not long after arriving in St. Louis, Scott Joplin found the Silver Dollar, and for the next seven years he was to be a constant visitor to the saloon, which would serve as one of the most important "schools" he would ever attend.

There was constant competition among the musicians who frequented the Silver Dollar, and though they were as supportive as a family to young and talented newcomers, they were also the harshest of critics to those whose pretensions outweighed their skill or creativity. One had to earn the respect of the Silver Dollar crowd, and by all accounts Scott Joplin did so. He particularly impressed his fellow musicians with his improvisational and compositional abilities, skills he had shown even as a youngster in Texarkana. He also became close friends with John L. Turpin and his sons, who functioned at least officially as bartenders at the Silver Dollar.

They were large, burly young men. Some years before, Charles and Thomas had tried their hand at mining, and had spent some time at the Big Onion Mine in Searchlight, Nevada, (19) and they often regaled their listeners with stories of their adventures. They contrasted sharply with the slightly built, quiet Scott Joplin, but they liked him immediately. It is said that he had a magnetic quality about him that attracted people to him.

Tom Turpin shared Scott's interest in music and also aspired to a musical career. Within a short time, due to his being "talked up" by Turpin and other musicians, Joplin was able to play in other Chestnut Valley establishments as well as in surrounding towns and cities. The excellent transportation network around St. Louis made it possible for Joplin to make frequent brief trips to Hannibal, Carthage, Columbia, and Sedalia and occasional longer journeys to Cincinnati and Louisville.

He always played in saloons and brothels, in the sporting districts of the cities he visited. As a young Black man, he had few other forums for his music. One was the Black church. Considering his quiet temperament and his desire for respectability, the church atmosphere might have suited him better, but it was impossible to make a living playing in churches. Besides, church music did not allow for Joplin's creativity. Such opportunities could only be found in the sporting districts. Another was one of the local Black bands, but a musician had to be settled in a locality to play with such a band.

One could still dream, however, particularly when one's dream was shared by a friend. Tom Turpin, five years Joplin's junior, also wished for a more respectable career, one that would be creative and lucrative and not be confined to bawdyhouses and saloons. Like Scott, he was not merely a performer but a composer as well. In 1891 he listed himself in the St. Louis City Directory as a musician rather than as a bartender.

Scott did not list himself in the city directories at all, and it is likely that he was traveling a great deal at this time and perhaps staying with the Turpins at 1422 Market Street, or at 9 Targee Street, where they moved in 1892, or renting a room here and there in the Chestnut Valley District. He was not and did not consider himself sufficiently settled to advertise as Tom Turpin did. He traveled around, performing wherever he could. While doing so, he was picking up more work songs, more folk dances and idioms. As ragtime musician and historian Trebor Tichenor says, "Joplin was a musician who could store away things that he heard and bring them out later. Classical European composers do this all the time, too, take folk material and use it in their own style, in their own way." (20)

At the time, however, Joplin had no realistic aspirations to be a composer. Although he and Tom Turpin had often talked about composing in earnest and getting their compositions published, they, and particularly Scott, were highly aware of the odds against their ever doing so. At that time, few Blacks had ever published. And then there was the problem of the type of music they played. It was associated with lowlife Blacks, saloons, and bawdyhouses; it could hardly attract the mass market. It was not the sort of music that was generally written down. Scott could have written down his compositions and, according to legend, was urged to do so, but he did not. In a natural defensive reaction, he was not interested in doing anything he believed to be futile.

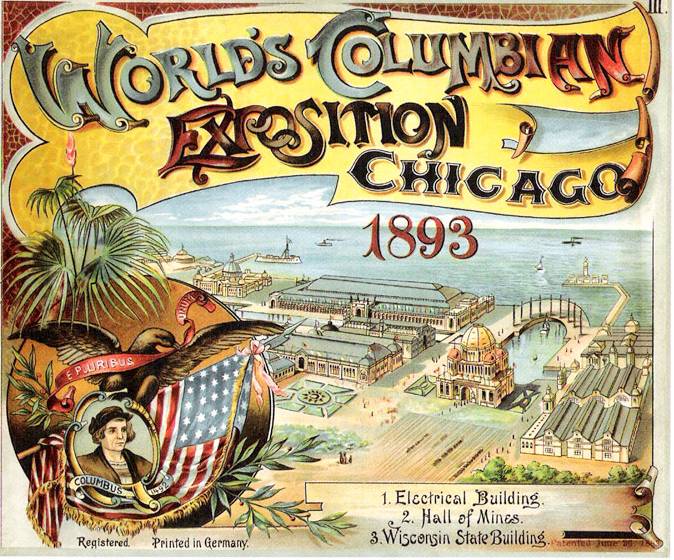

A turning point in Joplin's thinking and in his career seems to have occurred in 1893, when he journeyed to Chicago, site of the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition. (21)

The very idea of a world's fair was still so new and exciting in the 1890s as to be difficult for later generations to understand. Anyone who could afford it, and many who couldn't, managed to visit the city that year, and accordingly anyone who could make money from that huge influx of people managed to get there, too.

As was customary, the itinerant musicians were relegated to the fringes of the event, but as was also customary, they made the most of their opportunities on the fringe. A sporting district soon ringed the fairgrounds, providing, with Chicago's established tenderloin district from Eighteenth Street to the Illinois Central Railroad tracks, racy entertainment for the out-of-town visitors who could not have known to what a formidable array of talent they were privy. There, Scott met musicians whose experience was different from his own but whose ragged time music was similar in many respects. It broadened his perspective to learn that others, coming from different areas, could have adopted a similar musical form to express their experience. He was particularly impressed with two of Chicago's most prominent ragged time pianists, "Plunk" Henry Johnson and Johnny Seymour.

Joplin formed his first band in Chicago. It probably consisted of a cornet, clarinet, tuba, and a baritone horn. In arranging pieces for the band, he developed his instrumental notational ability. (22) He also met fellow pianist Otis Saunders, a native of Springfield, Missouri, and two years his junior, who was in Chicago for the fair. The two became close friends, and Saunders proved very important to Joplin, for he admired Joplin's piano compositions and convinced him to write them down.

No doubt Joplin had received such encouragement before, but his stay in Chicago probably was the first time when he began to believe that Black music and music by Blacks might have a chance at respectability. The Creole Show, an all-Black revue which had opened in 1891, played a whole season at the World's Fair in 1893. Although its performers were veterans of the minstrel circuit, the show was anything but in their tired minstrelsy tradition. It broke tradition by dispensing with blackface and by emphasizing not only music but musical talent, bringing dancing and singing to the fore and de-emphasizing the banal jokes and skits. Another revitalized minstrel show played at the fair that year. W. C. Handy's "Mahara's Minstrels" incorporated strains of Memphis and Mississippi music never before heard in the music of a show. Scott Joplin recognized it, and he recognized, too, a new respectability accorded Black music, a respectability still in its infancy, to be sure, but unmistakably present.

In 1894, Scott Joplin and Otis Saunders left Chicago and together made their leisurely way to St. Louis, stopping frequently to perform in saloons and cafes and bawdyhouses. They arrived back in St. Louis in late 1894 or early 1895 and found that the Turpins had established a new business. John now served as manager of Tom's new restaurant at the site of their former residence, 1422 Market Street, above which they now lived once again. Robert and Charles had gone their separate ways. Joplin confided to the Turpins that he had changed his mind. He had begun to write down some of his original compositions and intended to try to get them published. His experience at the World's Fair in Chicago had given him reason to be optimistic, and Otis Saunders had caused him to believe his work was good enough to sell, even if he was a Negro. Tom Turpin also decided to try to sell his compositions. It was a frightening but hopeful time for both young men. Joplin did not stay long in St. Louis. Whether it was wanderlust, or prodding from Saunders, or insecurity about his ability to write publishable compositions, he did not try to establish another band. Instead, he and Saunders continued on to Sedalia, Missouri, where in 1895 his brothers Robert and Will joined him. (23)

Scott had kept in touch with his family, (24) and his reports of the opportunities for traveling musical entertainers excited Robert and Will. Robert was about twenty-six and had worked for a time as a laborer in Texarkana, boarding at 830 Laurel Street with his father and Laura Joplin. Will was about nineteen and had been working as a porter at the McCarthy Hotel in Texarkana. (25) Both had maintained their interest in music. Will sang and played the violin and guitar, and Robert, in addition to singing and playing several musical instruments, had also tried his hand at composing popular songs. With Scott they revived the Texas Medley Quartette, which was not actually a quartet this time either but an octet or double quartet. Scott served as leader, conductor, and soloist. Robert sang baritone and Will tenor. Other members were: John Williams, baritone; Leonard Williams, tenor; Emmett Cook, tenor; Richard Smith, bass; and frank Bledsoe, bass. The group traveled extensively under the auspices of Oscar Dame and the Majestic Booking Agency. Toward the end of 1895 they probably appeared in or around Syracuse, New York, for Scott Joplin's first two songs were published in that city. (26) Leiter Bros. published "A Picture of Her Face" and M. L. Mantell issued "Please Say You Will," whose title page bore the inscription "Song and Chorus by Scott Joplin of the Texas Medley Quartette." (27)

Although both songs are well constructed and harmonized, they indicate Joplin's initial desire to "play it safe" in attempting to get his work published. Neither contains intimations of his later instrumental genius. Both are typical sentimental ballads of the era, whose most popular hit was "After the Ball," published in 1892 by Charles K. Harris. Judging from the lyrics of the songs in this genre, the Gay Nineties were misnamed. These were the words Scott Joplin wrote for "A Picture of Her Face," a song in waltz time:

This life is very sad to me, a sorrow fills my heart,

My story I will tell you, from me my love did part,

The village church bell sadly tolled, the one I loved had died,

She was a treasure more than gold, when she was by my side.

But now she's gone beyond recall, in a silent tomb she sleeps,

The one I loved yet most of all has left me here to weep;

Though death so ruthless stole my love, my dear and only Grace,

I've yet a treasure in this world, a picture of her face.

(Refrain)

It brings joy to me when ofttimes sad at heart,

Her picture I can see, and sad thoughts then depart;

Although my love is dead, my only darling Grace,

My eyes are ofttimes looking on a picture of her face. (28)

These two songs probably sold modestly well, for it was an era when nearly every parlor had its square or upright piano and sheet music sold for under half a dollar. Piano benches were frequently made large enough to store hundreds of copies of such music. However, these songs of Joplin's could hardly compare to the success of a song like "After the Ball," and perhaps it is best that they did not. For if they had, by circumstance Scott Joplin might have continued writing chiefly in this genre and not ventured as wholeheartedly into instrumental and particularly ragtime composition.

Having published two songs, Joplin was encouraged to compose more works and try to get them in print, and in 1896 he published three compositions in Temple, Texas, once again presumably while with the Texas Medley Quartette in Louisiana and Texas. All three were instrumental works, a waltz and two marches, and their order of publication seems to indicate Joplin's imaginative development and growing boldness. The first to be published was "Harmony Club Waltz," issued by Robert Smith. (29) Smith also published the second, "Combination March." Both compositions compared favorably with other published marches and waltzes of the time, but, like Joplin's two ballads, they were not particularly distinguished. The third work is different. "Great Crush Collision March," published by John R. Fuller under the agency of Robert Smith, is in some ways a novelty piece, and it may have been intended as such. The sheet music cover contains the blurb, "Dedicated to the M. K. & T. Ry.," (Missouri, Kansas & Texas Railway), and it is possible that a collision had occurred in 1896 in or near Temple, through which the road ran. Joplin may have written the piece under the inspiration of the event; or he may have added sound effects and descriptive narrative to an already completed work to make it timely and cause it to fit the event. It is the first of Joplin's published compositions to contain between-the-lines notes indicating the spirit in which certain passages were to be played—"The noise of the train while running at the rate of sixty miles per hour"; "Whistling for the crossing"; "Noise of the trains"; "Whistle before the collision"; "The collision." Discords become higher and more piercing as they build up to "The collision," which is marked by a crashing fortissimo chord in the base, and in these days when commercial arrangers did not know how to notate anything but regular or "square" meter, such descriptive sections were absolutely necessary. It has been suggested, however, that in his own playing of the composition Joplin would have infused it with considerable syncopation, and that "Great Crush Collision March" is the first publication of Joplin's to contain elements of ragtime. (30)

The Texas Medley Quartette ended this, their last, tour in Joplin, Missouri, in 1897, after which the group disbanded. With Saunders, (31) Scott made his way to Sedalia, which would serve as his base for the next four years. Although he was now a published composer, financially he was not much better off than he had been before his compositions were published. It is unlikely that the terms of his agreements with his publishers included royalties. The common practice among small publishers was to pay twenty-five dollars or fifty dollars outright and acquire all rights to the compositions they purchased. Even if Scott managed to negotiate a contract providing for royalties, his earnings would have been minimal. None of these early works of his were hits, and at the customary 5 per cent royalty rate, many thousands of copies of forty-cent or fifty-cent sheet music would have to be sold to net him more than pin money.