4 Chapter IV: Sedalia

Located near the center of Missouri about one hundred ninety miles west of St. Louis and eighty miles east of Kansas City, Sedalia was not yet forty years old when Scott Joplin arrived. Like many towns, it owed its existence to the railroad. In 1859 General George R. Smith, who had learned that the right of way for the Missouri & Pacific road was projected through the area, had purchased one thousand acres along the surveyed route and marked out the boundaries of a small town amid the rolling prairie hills. He called it Sedville for his daughter Sarah, whom he affectionately called “Sed.” Within a few months he had expanded the boundaries and planned a larger town to which he gave the more pleasant-sounding name Sedalia. It was settled in 1860 and the following year the railroad arrived. The town grew quickly after that and by 1895 Sedalia was a prosperous community with a population of some 15,000. It served as the Pettis County seat, the site of the annual Missouri State Fair and a terminal and layover point for not only the Missouri & Pacific but also the Missouri, Kansas & Texas, the railroad to which Scott had dedicated his “Great Crush Collision March.”

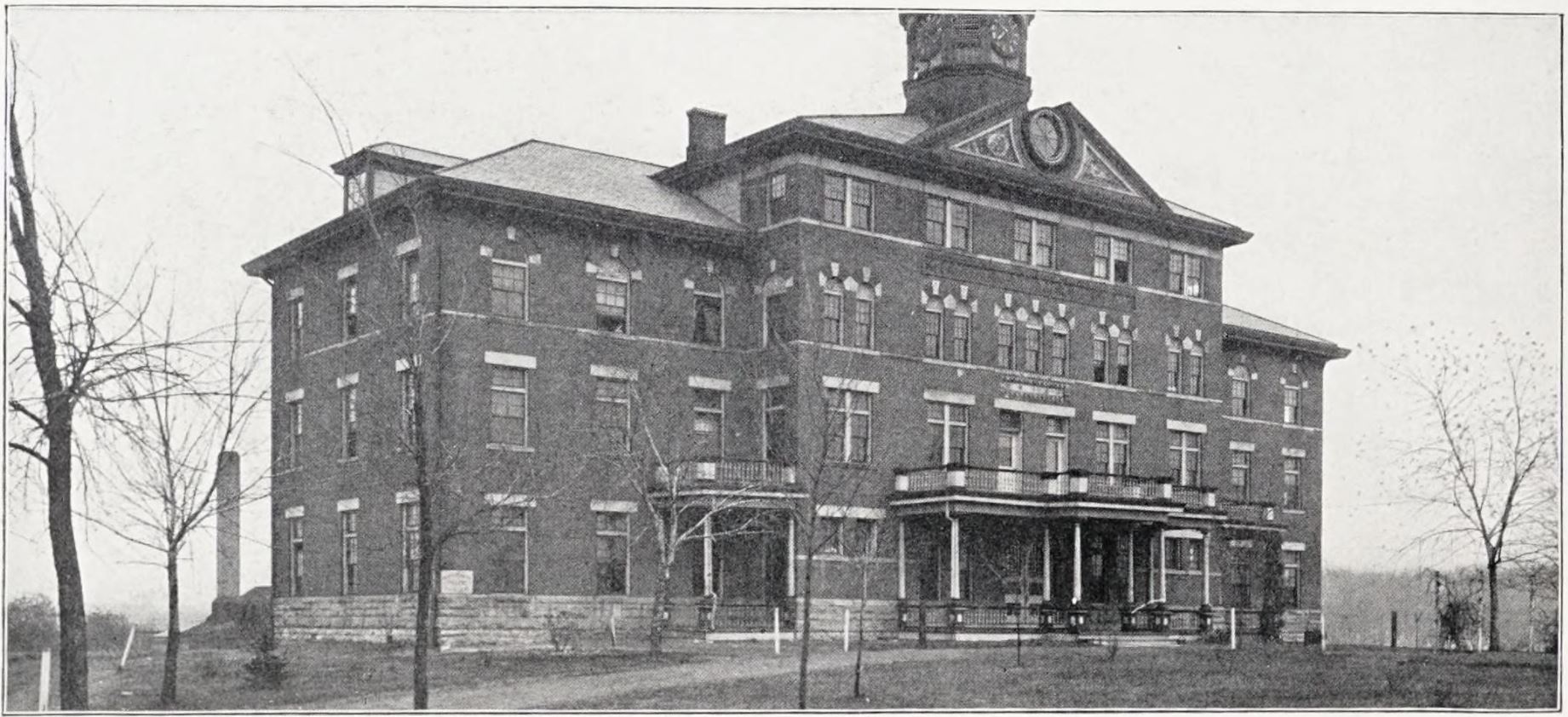

During the Civil War, Sedalia had been a Union military post, and this factor, combined with the numerous opportunities for agricultural work and railroad jobs, had attracted a sizable Black population. Though Blacks were segregated in housing and in social areas (unlike St. Louis directories, the Sedalia city directories identified Blacks as “(col)”), the Sedalia Black community was more prosperous than that of St. Louis. It supported several newspapers, among them the St. Louis Palladium, and boasted the George R. Smith College for Negroes, established by Smith’s daughters and later operated by the Methodist Church.

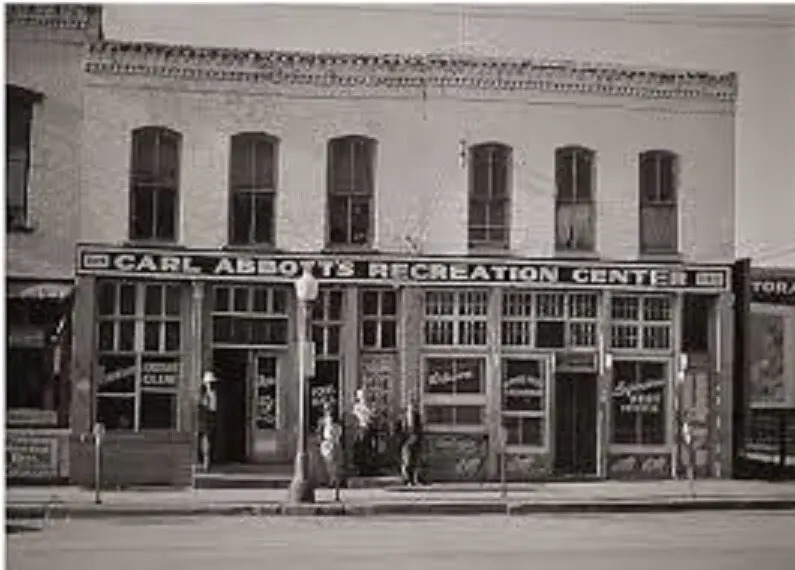

Sedalia also had the distinction of having one of the largest sporting districts in the state. The area, located in the vicinity of Lamine and Main Streets, included more than thirty saloons and attracted a large number of performers, among them Blind Boone, who would offer to pay a thousand dollars cash at his performances to anyone who could play a rag or song that Boone could not duplicate note for note after hearing it just once—and who never had to pay up. (1) Work was plentiful, particularly for those piano players who were facile at playing the new ragtime music, which was already popular in Sedalia and which was beginning to be played in other parts of the country as well.

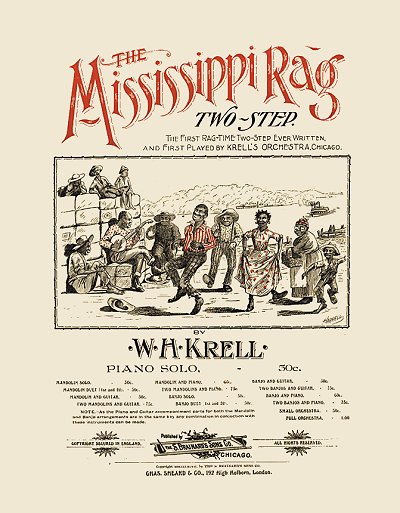

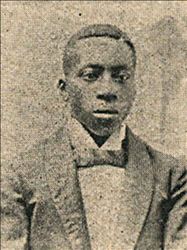

In January 1897 the first true rag, “Mississippi Rag” had been copyrighted by white Chicago band leader William H. Krell, opening the way for the publication of thousands of others and a nationwide ragtime craze. In Sedalia in 1897 ragtime was still in its infancy, but there were in that one city a group of young men who would become among the most famous ragtime composers and performers. They would soon be joined and personally guided by Scott Joplin. When he arrived, however, Joplin was little more than another Black pianist, albeit a published composer with an immersement in his music more singular than that of most others. As Samuel Brunson Campbell, a young white pianist who would arrive in Sedalia in 1899, later wrote, “He liked a little beer, and gambled some, but he never let such things interfere with his music . . . He was then about twenty-nine years old, a very black negro, about five feet seven inches tall; a good dresser, usually neat, but sometimes a little careless with his clothes; gentlemanly and pleasant, with a liking for companionship. . . He and Saunders were inseparable. If one were seen the other wouldn’t be far off.” (2)

Now that he had been published, Joplin was eager to sell more works. But he realized his notational ability was deficient. Though he could improvise a fine piece of ragtime music on the piano, he had difficulty writing it down. According to Campbell, Joplin was then working at a tavern owned by Tony Williams, a Black man who played and taught piano. Williams encouraged Joplin to enroll in the Smith College of Music, part of the George R. Smith College for Negroes on the outskirts of town. Saunders concurred, and shortly thereafter Joplin did take further musical instruction at the college. While studying piano with Mrs. Minnie Jackson and theory and composition with a Professor Murray, (3) he continued setting down on paper his ragtime compositions before he was fully competent to do so. It is likely that he tried to place them with various Sedalia publishers and, finding no success there, journeyed east to Kansas City, where one tune was purchased by music publisher Carl Hoffman. Though it was not published until 1899, “Original Rags” seems an early Joplin composition, written before he had acquired a real facility for notating his music.

The title page of “Original Rags” contained the blurb “Picked by Scott Joplin, Arranged by Chas. N. Daniels.” It is the only Joplin publication known whose arrangement is credited to another. Considering that the composition was published in the same year as the famous “Maple Leaf Rag,” and is definitely inferior in quality, it is possible that Hoffman purchased the work, held it for a while not knowing quite what to do with it, hired Charles N. Daniels to arrange it, (4) and finally issued it two years later. Though the theory has been advanced that Daniels had simply “arranged to have the piece published,” and that Joplin actually did the arrangement himself, it is interesting to note that an article in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, published two years after “Original Rags” was issued, does not mention the composition as one of Joplin’s ragtime works. (5)

Its title notwithstanding, “Original Rags” is a simple composition, not a collection. The title probably refers to the fact that it contained several passages played in the new ragged time, a reference that seems to date the composition to a time when the term rag was not yet solidified in popular terminology as identifying a single tune. Whether or not Joplin did sell “Original Rags” in 1897, the distinction of being the first Black composer to publish a ragtime piece went to his friend, Tom Turpin, whose “Harlem Rag” was published in December 1897.

To support himself while attending the Smith College of Music, Joplin engaged in a variety of musical activities in both the lower-class and better class Black Sedalia societies. He joined Sedalia’s Queen City Concert Band, an all-Black group established in 1891 as the Queen City Negro Band. One of its members was Emmett Cook, who had been a member of the Texas Medley Quartette, and perhaps Cook used his influence to get Joplin into the band. Scott played first B-flat cornet, and under his influence this twelve-piece band became one of the first, if not the first, in the area to play ragtime. In addition, Scott took a nucleus of five pieces from this band—E-flat tuba, baritone cornet, clarinet, drums, and piano—and formed a smaller group to play at parties and dances in the area (6); not because such activity was particularly enjoyable for him but because there was money in it. (7) Elderly Sedalia residents remember dances given in a building at the present 306-308 West Second Street and at a dance hall then on the northeast corner of Main Street and Ohio Avenue. “It was about the time the cakewalk came out,” recalled one such elderly resident, “and Joplin and his friends really made music.” (8)

Joplin also worked in the taverns and bawdyhouses of the sporting district. His first steady job was in a white-owned and operated establishment which contained a tavern on the main floor and a gambling parlor on the second. All its customers were white. (9) Later, he played at the Black 400 Club at 108 East Main Street, a club that he frequented as a patron as well. (10) The club, owned and operated probably by W. J. Williams and presided over by C. E. Williams, (11) was also called the 400 Social Club and the 400 Special Club, and it combined elements of both Black lowlife and Black middle-class life. The cakewalk had been appropriated by whites, and cakewalk music as well as the dance itself had become something of a national craze by 1896, exposing the white general public to syncopated music, deliberately syncopated music, for the first time. Accordingly, the cakewalk had been readopted and refined by Blacks. Every summer the Black 400 Club sponsored an all-day outing that featured a picnic, games, and contests, and at the end a grand cakewalk to cap the day’s entertainment. S. Brunson Campbell recalled that Joplin claimed he had composed one of the first published cakewalks in honor of this annual event, calling it “The Black 400 Ball.” (12)

At the Black 400 Club, where he played primarily for fun, and at the white-owned taverns, where he played chiefly for profit, Scott Joplin impressed his listeners with his perfect pitch, his ability to make ordinary chords and harmonies sound different, his talent at syncopation and rendition of the new ragtime forms. The success of ragtime depended greatly on the quality of its performance, for while its forms indicated the reactions it should inspire, a skilled pianist was necessary to make them a reality, and became more and more necessary as classic ragtime came into being.

A rag’s introduction establishes the key of the first large section of the composition and, in its rhythm and tempo, sets the mood. It captures the attention of the listener and lets him know that a rag is beginning to take form. After these first four measures, the opening chorus commands the listener to pay attention by using syncopated elements over a steady base. The second chorus employs a wider range of elements and greater rhythmic complexity, causing the listener’s excitement to mount. Then, a calming element is introduced; a bridge acting as the device to reach the more relaxed and melodic third chorus. The next chorus, however, surprises and wakes up the listener. The elemental range is widened once more, it is infused with humor, and it has a “ride-out” quality that signals that the end of the rag is approaching. “It is as though the composer was saying through music—I have excited you, then I allowed you to calm yourself, now have fun—enjoy, for this is ragtime—’sir.'” The fourth chorus ends with a closing section, which unmistakably completes the tune. (13)

Before long, Joplin had attracted a group of talented young followers, among them Joe Jordan, Arthur Marshall, and Scott Hayden. Joe Jordan had been born in 1882 in Cincinnati and had come to Sedalia to hang out in the saloon district and learn from the veteran players. A gifted player himself, he had never had a piano lesson and could not read a note. For this reason, among others, he respected Scott Joplin, and later he took music lessons. “Ear players can’t do anything unless they hear it,” he used to say. “You can’t show them some music and tell them it’s going to be a popular song—they have to hear it to play it. How would you like to have the paper read to you all the time to know what’s going on?” (14)

Arthur Marshall, born in 1881 in Kansas City, was about sixteen years old when Joplin arrived in Sedalia and was already a musician of considerable talent. He became a classmate of Joplin at the Smith College of Music and before long also became an unofficial student of the older man. Joplin was invited to stay with Marshall in his rooms at 135 West Henry Street and he lived there during most of his Sedalia years. (15) Some seventy-five years later, Marshall would recall their getting together on the “old-time square piano” in his home. “Joplin would say, ‘go on, play that piece again, play that piece again,’ and we began to get together . . .” (16)

Scott Hayden was about the same age as Arthur Marshall and the two had attended high school together. Marshall introduced Hayden to Joplin and the three became close friends and musical collaborators. On many a night, the two younger men could be found behind a screen or curtain in the bawdyhouses and saloons where Joplin played, smuggled in by the older man because they were too young to enter by the front door.

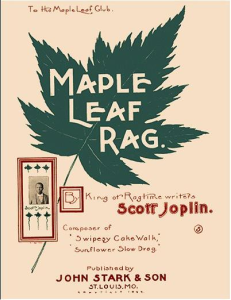

Joplin, meanwhile, had completed the first draft of “Maple Leaf Rag,” a composition the source of whose title continues to occupy the minds of Joplin scholars. It may have been named simply for the maple tree, one of the most abundant shade trees in Sedalia. It may also have been named after Florence Johnson’s “Maple Leaf Waltz,” which was popular in Sedalia at the time. (17) The Chicago Great Western Railroad had a route serving Chicago, Kansas City, and Minneapolis-St. Paul known as the Maple Leaf Route, because its route map resembled a maple leaf. Frank W. Cole’s 1895 composition “The Maple Leaf Two-Step” had been named for the route. (18) Given Joplin’s interest in the railroads, as indicated by “Great Crush Collision March,” this route may indeed have been the inspiration for the title of his composition.

At any rate, Joplin was pleased with the composition, his friends liked it, and he felt sure he could sell it. Sometime in 1898 he took it to a Sedalia music publisher, A. W. Perry & Sons, at 360 Broadway, but to his dismay the firm rejected it. A trip to Kansas City and a visit to Carl Hoffman’s firm also proved fruitless. (19) His friends encouraged him to continue working on the piece, and he liked it so much that he played it frequently in the clubs where he performed. He was gratified by its reception. Joe Jordan recalled hearing and liking the piece but suggesting to Joplin that he change its key. Originally, Joplin had played it in the key of A, since it was the easiest key for his band, which was composed mostly of A instruments. Jordan suggested that Joplin transpose it to A flat for publication to make it easier to read. Joplin followed Jordan’s advice but, Jordan recalled, could not play it in the new key as well as in the original. (20)

Otis Saunders was also convinced of the tune’s merit. Not only did he help Joplin rework the composition, but even before it was eventually sold he talked it up, not just in Sedalia but wherever he traveled. In his unpublished autobiography, S. Brunson Campbell explained how he was introduced to Scott Joplin’s music: “It was in 1898 that fate introduced me to Negro ragtime. A friend and I ran away to Oklahoma City to a celebration being held there. We became separated and I wandered into the Armstrong-Byrd music store and began to play some of the popular tunes of the day. A crowd gathered to listen, encouraged me with applause and called for more. After a time a young mulatto, light-complexioned, dressed to perfection and smiling pleasantly, came forward. He placed a pen-and-ink manuscript of music in front of me entitled ‘Maple Leaf Rag,’ by Scott Joplin. I played it and he seemed impressed. (He afterwards told me I had made two mistakes.) He turned out to be Otis Saunders, a fine pianist and ragtime composer, a pal of Scott Joplin and one of ragtime’s first pioneers. I learned from him that Joplin was then living in Sedalia and that he, Saunders, was joining him there in a few days.” Although he did not mention it to Saunders, Campbell was already making up his mind to go to Sedalia, too.

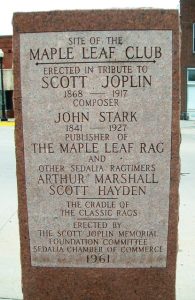

In December of 1898 the Maple Leaf Club applied for official legal status as an organization. The “Articles of Agreement for the Maple Leaf Club of Sedalia, Missouri,” dated December 23, 1898, read in part: “The objects and purposes for which this organization is created is to form and maintain a club, and to maintain a club house for the purpose of advancing by social intercourse the bodily and mental health of such persons as might be or hereafter become its members, and by the friendly interchange of views and discussions, advance the interests of its members; to obtain a place of common and friendly intercourse of such members with each other, to maintain a library for its members, other spheres of amusement and entertainments for the benefit of its members.” The board of directors for the club’s first year were: H. L. Dixon, President; Thomas Tompkins, Vice-President; A. E. Ellis, Secretary; W. J. Williams, Treasurer; and W. B. Williams. Among the first thirty members were Scott Joplin and Arthur Marshall. (21)

Although Joplin’s “Maple Leaf Rag” was not yet either purchased or published, it is possible that the Maple Leaf Club was named for the work. As stated earlier, the composition was popular in Sedalia before it was accepted for publication. However, it is also possible that “Maple Leaf Rag” was named for the club, which could have been in existence in some form for some time before official recognition was sought. (22) Indeed, a charter may have been applied for to allay criticism of the club. On January 18, 1899, the Sedalia Democrat published the following item:

The Colored ministers of the city have made request of the city officials that the Black 400 Social Club and the Maple Leaf Club be closed. ‘By permanently putting an end to these abominable loafing places—hot beds of immorality you will stop a great source of vice, create a better moral atmosphere for our young people, and render some of our homes happier.’

There was no rebuttal from the Maple Leaf Club, but C. E. Williams, president of the Black 400 Club, requested space for this statement in response:

That the Black 400 club room is a den of immorality is not true, and no eyewitness will say so. At the dress balls 40 of the best white people of Sedalia were in attendance as spectators . . . The doors of the club room are always open for the admission of the officers of the city to see what is going on. (23)

Apparently, the Black ministers’ appeal went unheeded. The February 15, 1899, issue of the Democrat contained the report: “The Black 400 gave a Valentine ball last night and the Maple Leaf Club also kept open house.” (24)

Besides being a charter member, Scott Joplin also became resident pianist at the Maple Leaf Club, and naturally “Maple Leaf Rag” was his most popular number. In club publicity he was called “the entertainer,” as the blurb on the back of a club business card shows. The front of the card read simply: “The Maple Leaf Club, Sedalia, Mo. 121 East Main St., W. J. Williams, Prop.” On the back was printed the following:

The Good Time Boys

William’s Place, for Williams, E. Cook, Allie Ellis, Taylor Williams. Will give a good time, for instance Master Scott Joplin, the entertainer. W. J. Williams, the slow wonder said that H. L. Dixon, the crackerjack around ladies said E. Cook, the ladies masher told Dan Smith, the clever boy, he saw Len Williams, the dude, and be said that there are others but not so good. These are the members of the “Maple Leaf Club.” (25)

One twenty-one East Main Street was a wooden building on whose ground floor was located the Blocher Seed Store. (26) The Maple Leaf Club was on the second floor, equipped with a large bar and probably filled with pool and gaming tables. Hanging gas lamps situated over the bar and tables scarcely illuminated the piano in the far corner, and the smoke and sounds of conversation often obscured the view and the sound of the ordinary performer. But not on a night when Scott Joplin was there. Decades later, at the age of eighty-eight, Arthur Marshall would recall how the rafters shook when “Scott took the stool at the ole ’88 in the Maple Leaf.” (27) Tom Turpin would come to the club on his visits to Sedalia, and nearly every itinerant pianist made it a point to go to the Maple Leaf Club to hear Joplin while he was in town.

“Original Rags” was published early in 1899. Joplin could not have been very pleased with the cover, which showed an old “darkie” picking up rags in front of a tumbledown shack. It was the type of “coon cover” that was popular at the time, and Joplin probably understood that Hoffman’s cover choice was simply in the current vogue. “Original Rags” was not of much concern to Joplin, however, for though it was his first published rag already he had developed far beyond it. His “Maple Leaf Rag” was, in his opinion, a fine composition. On the advice of his friends he had reworked it into what he felt was a highly salable piece.

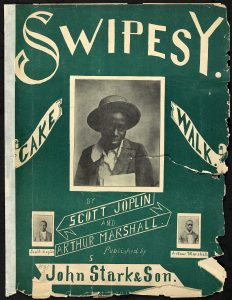

While reworking “Maple Leaf Rag,” Joplin was working with his protégés Arthur Marshall and Scott Hayden on what would be called “Swipesy—Cake Walk” and “Sunflower Slow Drag—A Ragtime Two-Step” respectively. Of the two, the Hayden collaboration progressed more quickly, for Joplin was attracted to Hayden’s young widowed sister Belle. He was a shy man, and not one to declare himself openly, and thus he used the collaborative effort as an excuse to spend a considerable amount of time at the Haydens’ rooms on 133 West Cooper. Joplin took the manuscript for “Sunflower” along with a reworked version of “Maple Leaf Rag” when he visited the offices of John Stark, located at that time at 114 East Fifth Street in Sedalia in the summer of 1899. He had not gone to Stark earlier because the company published primarily sentimental parlor piano music. That Joplin did eventually go to Stark and that the publisher discerned the potential in the music he offered is one of the happy events of history.

John Stark was born in Shelby County, Kentucky, in 1841, and had left home when the Civil War broke out, becoming a bugler in the Indiana Heavy Artillery Volunteers. After the war, he and his bride set out in a covered wagon to homestead in the area of Maryville, Missouri. Finding the life of a homesteader not to his liking, Stark eventually turned to selling musical instruments. In 1883 he moved to Sedalia and established a music shop at 222 Ohio Street, where he concentrated on selling pianos and organs. “They used to drag an organ out to a farmer’s house in an old wagon and leave it there for a week,” the widow of Stark’s son, Will, recalled years later. “When they came back, the farmer invariably had become so attached to the instrument, that he would buy it.” (28)

In 1885, at the age of forty-four, he established his sheet music business, John Stark & Son, with one of his sons, Will. It was a modest enterprise. The two men operated their one handpress themselves and worked not in business suits but in overalls. And the composers whose work they published were frequently friends and members of the family, among them John Stark’s son E. J. (Etilmon Justice), who composed typical nineteenth-century parlor music before the ragtime craze and who later published rags under the name Bud Manchester. A number of the early Stark publications were actually E. J. Stark’s pieces published under pseudonyms. (29) Works by other composers were usually purchased for little money, often only a small percentage of the royalties and no outright purchase amount, and because they operated on a shoestring the Starks favored “safe” pieces and took few risks on music that they were not sure would sell. It took a talent like that of Scott Joplin to cause them to change their policy.

Scott Joplin entered the Stark establishment one day in August 1899, carrying the manuscripts for “Maple Leaf Rag” and “Sunflower Slow Drag” and accompanied by a small boy who had probably been conscripted for the occasion. Dance being the basis of ragtime, Joplin may have realized that a demonstration of the “danceability” of his compositions would make them more salable. As Joplin played “Maple Leaf Rag” and then “Sunflower Slow Drag,” the little boy did a dance, impressing both Stark and son. Although the elder Stark was apprehensive, feeling the compositions were too difficult for the average person to play, Will Stark was so taken by the child’s dance that he decided to buy at least one of the compositions and accepted “Maple Leaf Rag,” (30) beginning one of the legendary relationships in American music history. In the years to come, though they had differences, Stark, the white businessman, and Joplin, the Black composer, dealt with each other from positions of mutual respect, a remarkable relationship for the times.

On August 10, 1899, John Stark and Scott Joplin signed a contract setting forth the terms under which the firm would publish “Maple Leaf Rag.” Scott received no money up front and he was to receive a royalty of only one cent per copy sold. (81) But he was intent on having his work published and willing to agree to almost any terms. In fact, so great was his desire to see his work published that he was shortly to sign an exclusive five-year contract with John Stark & Son. (32)

This, in itself, was quite a remarkable event. At the time it was not common to publish works by Black composers, and those whose works were published were frequently exploited. White publishers could purchase a tune or song for ten dollars and reap a considerable profit. The hapless composers would take anything to see their work in print. John Stark was not above such exploitation, as the contract for “Maple Leaf Rag” indicates; yet he was remembered with fondness by Black composers of the era and regarded as a pioneer for purchasing rags in the early years of ragtime. “John Stark was a very far-sighted man,” Joe Jordan once observed. “Nobody would publish rags in the early years.” Jordan sold his biggest hit, “That Teasin’ Rag,” for twenty-five dollars. (“I thought I was holding the man up!”) Later Stark purchased many rags for twenty-five or fifty dollars, and these were large sums for itinerant composers. (33)

“Maple Leaf Rag” was published in September 1899. The actual music was printed in St. Louis, but it is still called the Sedalia Edition. (34) Its cover was far more tastefully done than that of “Original Rags,” and this would be one characteristic of the Starks’ business that would please Joplin. While their covers would be designed for salability, they would not be exploitative. In fact, the cover illustration for “Maple Leaf Rag” was the most exploitative of any of Joplin’s works published by John Stark & Son. It depicts two Black couples in decorous dress as if engaged in or on their way to a cakewalk, an illustration not originated in the Stark minds but used by permission of the American Tobacco Company, which employed it in their advertising for Old Virginia Sheroots. The Stark firm was not large enough to commission original covers at that time. Clearly, the use of the cakewalk association was to take advantage of the current cakewalk craze. Unfortunately, the cover had not the desired effect. “Maple Leaf Rag” was hardly a smash hit at first. As John Stark later said, “. . . it took us one year to sell 400 copies, simply because people examined it hastily, and didn’t find it.” (35)

The reference is probably to the lilting tune. In those days before radio and phonograph, far more people were able to read music than today. Likely, they skimmed the notes and either decided the tune was too difficult or did not discern its charm. What would eventually sell “Maple Leaf Rag” was word-of-mouth advertising, hearing the piece played in music shops and in saloons and taverns. But at first it was a slow seller, and at fifty cents a copy it was not making either publisher or composer rich. At one cent royalty per copy, Scott Joplin made exactly four dollars in the first year after the piece was published, hardly a big score. He still had to perform in a variety of capacities in order to support himself and he and his band were in considerable demand to play at community functions. The Sedalia Democrat, August 4, 1899, carried the following in an article about the Celebration of Emancipation Day at Liberty Park:

Fourth of August Musicale—Scott Joplin, assisted by John Williams, Lynn Williams, Frank Bledsoe, Arthur Channel and Richard Smith, will render the programme.

He also continued to play at the Maple Leaf Club, where in 1899, fifteen-year-old Samuel Brunson Campbell found him.

As Campbell later wrote, in his autobiography, “I headed for Sedalia and after riding in box cars, cattle cars, and blind baggage, I finally reached there and lost no time seeking out Otis Saunders and Scott Joplin . . . At Saunders’ request I played for Joplin. They both thought I played fine piano and Joplin agreed to teach me his style of ragtime. He taught me how to play his first four rags, the ‘Original Rags,’ ‘Maple Leaf Rag,’ ‘Sunflower Slow Drag,’ and ‘Swipesey Cake Walk.’ I was the first white pianist to play and master his famous ‘Maple Leaf.'”

To be sure, ragtime in general and “Maple Leaf Rag” in particular took some mastering. In typical ragtime form, it consisted of four different tunes or strains, each sixteen bars long. The first strain was sophisticated in its harmony, pleasing in its perfection. The second strain was in a “dance” style, similar to that in “Original Rags.” The third strain was the one now most featured and frequently played, because of its exciting march rhythm and its pounding agitation. Unlike Joplin’s later compositions, it could be played extremely fast without detracting from it, and in fact could not be played slowly and retain its lightness. There was a happy feeling about it, and an impulse to dance that was irresistible. But it had to be played properly for this impulse to be transmitted. The Starks acknowledged this difficulty in one of their later advertisements:

We knew a pianist who had in her repertoire, “The Maple Leaf,” “Sunflower Slow Drag,” “The Entertainer” and “Elite Syncopations.” She had played them as she thought, over and over for her own pleasure and others, until at last she had laid them aside as passé. But it chanced that she incidentally dropped into a store one day, where Joplin was playing “The Sunflower Slow Drag.” She was instantly struck with its unique and soulful story, and—what do you think? She asked someone what it was. She had played over it and around it for twelve months and had never touched it. (36)

Many who tried to play ragtime from sheet music played it less than they played at it, and quite a few didn’t even try. This was one reason why “Maple Leaf Rag” did not sell well at first. Another reason was that ragtime had not yet become a national craze. To many, perhaps the majority of Americans, it was still associated with lowlife Negroes and red-light districts and was hardly entertainment suitable for polite society.

Scott Joplin was deeply aware of this attitude and pained by it. More than anything else, he wanted so-called Negro music to be respectable, understood for its possibilities, seen for what it was, not burdened with negative associations. “As early as the turn of the century,” Campbell would recall much later, “Joplin had the idea that his fine ragtime music could stand up with the best of the so-called ‘better music.’ . . . He thought his music unappreciated and once said, ‘Maybe fifty years after I am dead it will be.’” (37)

Joplin was determined to win respectability for ragtime. For some months before “Maple Leaf Rag” was published he had been at work on a piece unheard of for the time, a dramatic ragtime folk ballet. Based on Black social dances of the era, The Ragtime Dance consisted of a vocal introduction followed by a series of dance themes directed by the vocalist: Ragtime Dance, Clean Up Dance, Jennie Cooks Dance, Slow Drag, World’s Fair Dance, Back Step Prance, Dude Walk, Sedidus Walk, Town Talk, and Stop Time. In retrospect, it can be seen as a logical early step in Joplin’s development toward full-length opera. But in the fall of 1899 it was a rather strange and somewhat pretentious undertaking for a man who had published relatively few compositions and only two ragtime compositions, none of which had sold particularly well as yet, despite the local popularity of the “Maple Leaf Rag.” And it was highly pretentious for a Black man.

Scott Joplin, however, was not a practical man. His desire to make ragtime music respectable outweighed any misgivings he might have had about the reception of his folk ballet. And perhaps his popularity in and around Sedalia—the sheer idolatry with which his young proteges viewed him—clouded his vision. They praised his work, helped him with it; Arthur Marshall spent weeks copying in longhand the many parts of the orchestration. Joplin’s brother Will encouraged him. It is understandable that for a brief, heady time Scott Joplin thought he might be able to influence the path of ragtime and change the predominant attitude about Negro music.

Joplin formed the Scott Joplin Drama Company, whose members included Will Joplin and Henry Jackson, with whom Scott would later collaborate on a song. (38) Late in 1899 he rented the Woods Opera House in Sedalia for a single performance, which he hoped would be sufficient to arouse excitement about the composition, for a single performance was all he could afford. He invited nearly everyone he knew, including the Stark family, and no doubt let it be known to the others that a favorable reception to the piece might influence the Starks to purchase the ballet for publication.

The curtain went up. In the orchestra pit below, Scott Joplin on piano conducted the small orchestra that was the nucleus of the Queen City Concert Band. On stage, before a simple scenery backdrop, Will Joplin sang his introduction, then acted as a caller as four couples dressed in their own most festive clothing danced the various steps. When it was over, the audience applauded heartily, but John Stark was not moved to purchase the composition. “Maple Leaf Rag,” after all, had not been out long and had not begun to sell at any great pace. This was an ambitious undertaking and Stark was too good a businessman to take such a gamble. In his opinion Joplin had not yet proved the marketability of his works, and this was far from the ordinary rag anyway. In retrospect, Joplin showed bad timing; but even if he had waited until “Maple Leaf Rag” had really begun to sell he probably would not have been successful in convincing Stark to publish The Ragtime Dance. It was too far ahead of its time. Even so, Joplin blamed John Stark for his lack of foresight. The matter of The Ragtime Dance would linger in the background of their relationship and cloud it for some years to come.

Though Joplin was disappointed at Stark’s failure to purchase his ragtime ballet, he remained undaunted in his intention to keep setting down his ragtime compositions. They came easily to him, and with his training at the Smith College of Music they became increasingly easy to set down. Then, too, he was buoyed by the support and encouragement of his friends and protégés, who were constantly helping to spread his music and his name around Sedalia and its environs. One of these protégés was Samuel Brunson Campbell, who late in 1899 announced that he was leaving Sedalia. He wanted to return home to his family in Kansas, but everywhere he went, he informed his idol, he would play Scott Joplin’s rags. Just before he left, Campbell had an encounter with Joplin: “As I was leaving him and Sedalia to return to my home in Kansas he gave me a bright, new shiny half dollar and called my attention to the date on it. ‘Kid’; he said, ‘this half dollar is dated 1897, the year I wrote my first rag. Carry it for good luck and as you go through life it will always be a reminder of your early ragtime days here at Sedalia’: There was a strange look in his eyes which I shall never forget.” (39)

Scott Joplin, too, would always remember his days in Sedalia, for there he was the acknowledged “King of Ragtime” and was indeed referred to by that title. He had the city by its nose. He took, for example, to organizing ragtime playing contests, and performers from all over the state would come to compete with him. Many, especially those from St. Louis and Kansas City, were accompanied by rooting sections, but all the Sedalia people would favor Joplin. When it came time to choose the winner for the contest, he would always win by acclaim.

His name and his music were being spread at the same time in the other towns and cities throughout the Midwest by Samuel Brunson Campbell in Missouri, Kansas, and Nebraska and by Otis Saunders in Oklahoma City and Memphis. And Scott Joplin, too, traveled away from Sedalia at times, playing for college students and performing at least once in Warrensburg, Missouri. In some of the communities he visited, Maple Leaf Clubs were formed. (40)

By 1900 ragtime was becoming a national craze, and in fact it would give the new decade its popular name, the “Gay Nineties.” One reason for its popularity was the “amateur music movement.” In the decades since the Civil War the parlor piano had become the mainstay of American middle-class culture, and thus a music specifically or primarily for the piano was almost assured of popularity. But two other elements were important to the success of ragtime music. One was the emergence of the commercial music market as a major cultural force. Based in New York, this mass music market very shortly began to demand the new ragtime but in simpler form, and New York-based composers and musicians quickly created the supply to meet the demand. Beginning about 1900, these composers and musicians supplied the numerous New York music publishing firms with pieces marked by the syncopation of classic ragtime (classic ragtime is defined very simply by most musicologists as the music of Scott Joplin, James Scott, Joseph Lamb) but far simpler to play and much more commercialized. Their “tinny” sound gave rise to the name Tin Pan Alley, which the world of the New York-based ragtime musicians was called. True to the history of American music, these commercialists of ragtime were primarily white, had adopted and adapted a chiefly Black musical idiom, and were now busily engaged in popularizing it.

The other element was the perfection of the Pianola, forerunner of the player piano, a mechanism that enabled the piano to be played mechanically. A paper roll was passed over a cylinder containing apertures connected to tubes, which were in turn connected to the piano action. As often as a hole in the paper passed over an aperture, a current of air passed through a tube and caused the corresponding hammer to strike the string. The performances of the finest pianists could be reproduced with some skill. With the emergence in the United States of a strong middle class, the attitude that with enough money the proper results could be achieved had begun to prevail. Time is money, and if a middle-class family could afford a Pianola and piano rolls, then they did not have to waste time learning to play on a standard piano the tunes they wanted to waft through their front parlor. A lot of poor, commercialized ragtime was beginning to be published in both piano roll and sheet music form, but it did riot overshadow the more classic ragtime compositions. There was plenty of business to go around.

John Stark was convinced that “Maple Leaf Rag” could take advantage of this growing popularity, but he felt handicapped in Sedalia. He needed to be based in a larger city, and late in 1900 he and his son Will journeyed to St. Louis because, as Will Stark’s widow later recalled, “they thought they would have a better chance of putting it over here.” They set up shop in their hotel room and, operating a small handpress, turned out some ten thousand copies of “Maple Leaf Rag,” which they traded for a small printing plant at 3615 Laclede Avenue. (41)

John Stark & Son was still very much a one-horse operation, and in fact operated a tuning business during the first two years or so in St. Louis. (42) Wishing to establish themselves as a bona fide St. Louis publishing firm, the Starks made haste to issue a new title and chose “Swipesy—Cake Walk,” the Joplin-Marshall collaboration. Published at the end of 1900, the first Stark publication to bear the St. Louis address, “Swipesy—Cake Walk” is also the first true slow drag, as the instructions on the first page—”Slow”—indicate. Its variations of speed are meant to conform to similar variations in the dance that was the current rage, and it was specifically titled a cakewalk. Although it has not the imaginative flair of “Maple Leaf Rag,” it is a respectable work and does not deserve some of the criticism it has received from musicologists who feel that it is primarily a Marshall composition with a few Joplin strains inserted rather than a real cooperative effort. (43)

Stark designed his own cover for this composition, and though it depicts a small Negro boy it is done tastefully. According to legend Stark discovered the little newsboy squabbling out in front of his office one day, was taken with him, and decided to bring him in and have him photographed for the cover of the new composition. Looking at the photograph, Stark decided the boy’s shy expression was that of a child who had just been into the cookie jar. “Let’s call it Swipesy,” Stark said, and thus was the title of the composition born. (44) Many rag titles came about in just such a casual manner.

The little boy’s photograph was not the only one to grace the sheet music cover. Below him were two smaller photographs of the collaborative composers, the first and one of the few published photographs of Scott Joplin, a solemn-looking man in a three-piece suit, his stiff pose resembling that in a front-view police mug shot. Perhaps he was concerned that the public would be less likely to buy a composition whose writers were clearly identified as a Black. Many Black composers were aware that the public purchased their compositions thinking they were written by whites.

Sometime in the fall of 1900 “Maple Leaf Rag” suddenly took off. A flood of orders came in, many of them—perhaps the largest number—from the F. W. Woolworth five-and-ten-cent stores, and John Stark & Son was barely equipped to handle them. Shortly they hired a staff, exchanged their work clothes for business suits, and set up an operation more in keeping with the sort associated with the publishers of a work like “Maple Leaf Rag.” (45)

The St. Louis edition of “Maple Leaf Rag” had a different and considerably less interesting cover. In the spring of 1901 the cheroot business of the American Tobacco Company was transferred to American Cigar Company, (46) who apparently refused to allow further use of their illustration by the Starks. A cover illustration showing a simple maple leaf was substituted.

Back in Sedalia, Scott Joplin continued his composing and his performing at the Maple Leaf Club. While he was considering moving to St. Louis, there were things that held him back. One was his disagreement with Stark over the marketability of The Ragtime Dance. Joplin wanted the work published, and after Stark left Sedalia, the composer visited other publishers in the city trying to sell the work. While he was unsuccessful in selling The Ragtime Dance, he did manage to sell another rag, “The Favorite,” to A. W. Perry & Sons of Sedalia. (47) Clearly, Joplin was angry at Stark for not seeing the possibilities in The Ragtime Dance and thus did not feel totally obligated to the five-year contract between the two. Yet he did not wish to lose Stark’s friendship or his publishing business altogether. It is likely that he secured an agreement from Perry not to publish “The Favorite” until 1904, when the five-year contract, entered into in 1899, would be finished.

Then, too, Joplin was courting Belle Hayden and did not wish to leave her. By most accounts, Belle loved Joplin but was not in the least interested in music—his or anyone else’s. She would thus not have been particularly understanding of the reason for the move and would have preferred not to leave her family and friends. Sometime in late 1900 or early 1901, however, Joplin met a man from St. Louis who would have a strong effect on him and on his music and whose presence in St. Louis would make it even more important to Joplin to be there too. This man was none other than the legendary German music teacher whose identity would subsequently be one of the unsolved mysteries in the search for material on Joplin’s life. Joplin’s widow, Lottie, recalled after his death that there had been a German music teacher to whom her husband was indebted and to whom he sent letters and gifts after they had moved to New York. There can be little doubt that Alfred Ernst was this man. This author discovered the man’s identity by accident, while searching for suitable illustrations for this book.

The February 28, 1901, issue of the white St. Louis Post-Dispatch carried an article that departed from the paper’s usual type of reportage. Under the headline “To Play Ragtime in Europe” was a photograph of Scott Joplin, Black ragtime musician. The article read:

Director Alfred Ernst of the St. Louis Choral Symphony Society believes that he has discovered, in Scott Joplin of Sedalia, a negro, an extraordinary genius as a composer of ragtime music.

So deeply is Mr. Ernst impressed with the ability of the Sedalian that he intends to take with him to Germany next summer copies of Joplin’s work, with a view to educating the dignified disciples of Wagner, Liszt, Mendelssohn and other European masters of music into an appreciation of the real American ragtime melodies. It is possible that the colored man may accompany the distinguished conductor.

When he returns from the storied Rhine Mr. Ernst will take Joplin under his care and instruct him in the theory and harmony of music.

Joplin has published two ragtime pieces, “Maple Leaf Rag” and “Swipesey Cake Walk,” which will be introduced in Germany by the St. Louis musician.

“I am deeply interested in this man,” said Mr. Ernst to the Post-Dispatch. “He is young and undoubtedly has a fine future. With proper cultivation, I believe, his talent will develop into positive genius. Being of African blood himself, Joplin has a keener insight into that peculiar branch of melody than white composers. His ear is particularly acute.

“Recently I played for him portions of ‘Tannhauser.’ He was enraptured. I could see that he comprehended and appreciated this class of music. It was the opening of a new world to him, and I believe he felt as Keats felt when he first read Chapman’s Homer.

“The work Joplin has done in ragtime is so original, so distinctly individual, and so melodious withal, that I am led to believe he can do something fine in compositions of a higher class when he shall have been instructed in theory and harmony.

“Joplin’s work, as yet, has a certain crudeness, due to his lack of musical concatenation, but it shows that the soul of the composer is there and needs but to be set free by knowledge of technique. He is an unusually intelligent young man and fairly well educated.”

Joplin is known in Sedalia as “The Ragtime King.” A trip to Europe in company with Prof. Ernst is the dream of his life. It may be realized.

This was the first of only a few articles that would ever publicly recognize and laud Joplin’s talent during his lifetime. To be praised in such a way was to be accorded an honor known by few other Black musicians of the era, an honor Scott Joplin had never before experienced and would experience pitifully few times. Like his relationship with Stark, his relationship with Ernst would be quite singular for the era. He would be indebted to Ernst for the rest of his life, and as a result of Ernst’s influence, he would aspire to achievements few other Black musicians would dare consider: he would presume to write ragtime opera.

The reasons for making the move from Sedalia to St. Louis now far outweighed any reasons against doing so, and sometime probably in the early spring of 1901 Scott Joplin and Belle Hayden left Sedalia to settle in the Gateway City. (48)