6 Chapter VI: St. Louis

Arriving in St. Louis, Scott and Belle moved into a second-floor flat in a row house at 2658-A Morgan Town Road, (1) and in keeping with his new domestic status Scott began a more settled life, performing only rarely and concentrating on composing and teaching. He listed himself in the city directory as simply “Joplin, Scott, music.” Now that he was in the same city with his mentor, he spent considerable time with Ernst, who would shortly leave for Europe. Although there is no documentary evidence regarding Joplin’s whereabouts in the summer of 1901, it is unlikely that he accompanied Ernst, as the St. Louis Post-Dispatch hinted he might. (2) He and Belle had moved to St. Louis so recently and their financial condition was probably too modest for such an extravagance. Then, too, Ernst may have wished to introduce Joplin’s music to his countrymen before introducing them to its composer. Joplin probably remained in St. Louis that summer.

Not long after the Joplins arrived in the city, Scott Hayden followed them with his bride, Nora Wright, whom he had married in Sedalia. The couple also moved into the house on Morgan Town Road. Arthur Marshall had gone on tour with McCabe’s Minstrels, a popular group at the time, but other Sedalians, among them Otis Saunders, would visit frequently. In some ways it was as if an important segment of the Sedalia musical world had simply been transplanted to St. Louis. Certainly, Belle enjoyed these visitors and their news from home, and she later became closer than ever to Arthur Marshall, for one, although she still did not share or understand their interest in music.

For Scott, moving to St. Louis was like coming home. His younger brother Robert was living in the city, in rooms at 2617 Lawton Street, working as a cook. He had stayed in Texarkana and married, and with his wife Cora he’d had a daughter, Essie. But the marriage had failed, and although he was not as musically talented as his brothers, Robert enjoyed the excitement of the big city musical world. Perhaps as a result of Scott’s reports of this excitement in his letters home, Robert had decided to move to St. Louis and try to make a new beginning. Within the next year, Will Joplin would also move to St. Louis, taking rooms in a large rooming house at 2117 Lucas Avenue and listing himself in the 1902 city directory as “Joplin, William, music.” Once again, a segment of the Joplin family would be together.

And then there were the Turpins, with whom Scott had been so close during his earlier stay in St. Louis. Since Joplin had left St. Louis around 1896, the Turpins’ fortunes had risen and fallen with the speed of a roller coaster. Tom’s cafe, established in late 1894–early 1895 after his father’s Silver Dollar Saloon had closed, had itself folded within a year and Tom had been forced to work as a laborer. By all accounts, with his rugged physique—he is said to have weighed 360 pounds—and huge, meaty hands he looked more like a laborer than a composer-musician anyway. He had continued to work on his music and in late 1895, inspired by a trip to New York, had written his “Harlem Rag,” which he sold to DeYoung of St. Louis. Issued in 1897, “Harlem Rag” was the first rag by a Black composer to be published, and it would become a minor classic. DeYoung later sold the piece to Stern of New York, which printed it in two different arrangements. (3)

With the money and the optimism gained from the publication of his first rag, Turpin had opened another saloon at 100 N. Nineteenth Street, but this, too, had lasted only about a year. Another trip to New York, where a dance called the Buck and Wing was the rage, inspired his second published rag, “Bowery Buck,” issued in 1899. For a time around 1899, Tom Turpin had exchanged the insecure life of a saloonkeeper for the steady income of a police constable, but he had soon decided against such a career, preferring instead to work at menial jobs while pursuing his music, (4) while his father, John, operated yet another saloon. (5)

When Scott Joplin arrived in St. Louis, Tom Turpin was teaching music and functioning as a mentor to a number of talented youngsters, among them Joe Jordan, who had come from Sedalia a year or so before, Sam Patterson, and Louis Chauvin. All were in their late teens or early twenties, and all were seasoned performers. Chauvin and Patterson, seventeen and nineteen respectively in 1900, had been born next door to one another in St. Louis and had attended elementary and junior high schools together. Both had displayed early musical talent, and while Patterson had been given the benefit of lessons and Chauvin had not, Patterson always maintained that Chauvin was the more gifted player. Patterson had dropped out of school at the age of fifteen and Chauvin had quit too. He was thirteen at the time. That summer they went on the road with a company called the Alabama Jubilee Singers. Back in St. Louis, they formed a vocal quartet, the Mozart Comedy Four, and played the city’s red-light district as well as gigs in surrounding towns. They also continued to do piano performances. Whenever they were not working they could be found with Tom Turpin, picking up pointers on playing technique. Turpin’s technical brilliance was acknowledged throughout the district, although Charlie Thompson, who arrived in St. Louis around 1907, used to say he got more credit than he deserved because he was Scott Joplin’s “runnin’ buddy.” (6) They also exchanged ideas with Turpin. Chauvin was himself a talented composer, but he rarely perfected one strain or harmony before he was off on another. Turpin tried to persuade him to slow down and to think seriously about getting his work published, but Chauvin was unable to concentrate on any one tune for that long.

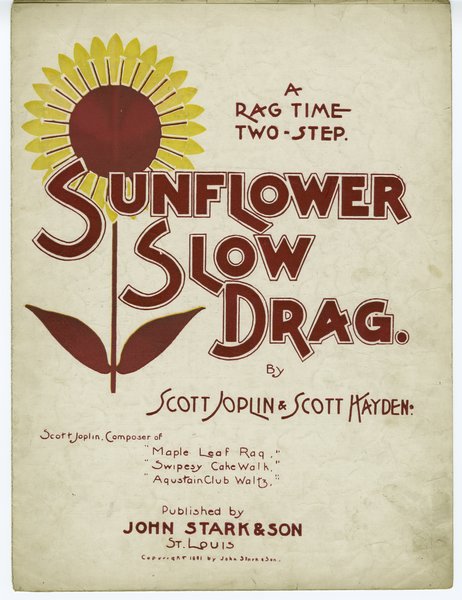

The interest in Joplin on the part of Alfred Ernst did not cause the composer to forsake his earlier friends of the red-light milieu. He rejoined the Turpin circle and was welcomed with great delight and pride. His “Maple Leaf Rag” was fast making him the most famous rag composer on the circuit, and in the early spring of 1901 three more tunes were added to his list of published works. The compositions, “Sunflower Slow Drag,” “Peacherine Rag,” and “Augustan Club Waltz,” had all been in Stark’s possession for some time. “Sunflower Slow Drag,” on which Joplin had collaborated with Hayden, was the other composition that Joplin had taken with him on his first visit to the Stark offices in Sedalia. The delay in publishing these new works had been due to the tremendous popularity of “Maple Leaf Rag” and the initial unpreparedness of the Stark firm to fill all the orders that came in. Enlisting the help of every member of the family as well as that of paid employees, the Starks had finally caught up with the backlog of orders and established facilities equipped to handle their mushrooming business, so that by early 1901 they were able to consider publishing new compositions. Encouraged by Joplin’s frequent reminders that they had new material of his that they were supposed to publish, and envisioning the coattail effect “Maple Leaf Rag” would have on sales of these new works, John Stark was just as eager to issue them as Joplin was to see them in print.

Probably “Sunflower Slow Drag” and “Augustan Club Waltz” were issued almost simultaneously, for each cover lists the other among Joplin’s earlier compositions. “Augustan Club Waltz,” dedicated “To the Augustan Club, Sedalia, Mo.,” is a typical waltz in the waltz tradition and is in no way a ragtime waltz. And yet it has a hint of Joplin-type ragtime charm, and some have identified elements of its second strain with his later composition, “The Entertainer.”

“Sunflower Slow Drag,” is in the cakewalk style of ragtime, and it is a truly inspired composition. Perhaps, as John Stark suggested in his advertisement, this inspiration came from Joplin’s courtship with Belle Hayden. Stark called it “a song without words,” and there are sections for which this is a perfect description.

It is likely that “Peacherine Rag” came later in the year. It is the first whose cover boldly proclaims, “By the King of Ragtime Writers, Scott Joplin,” and it lists the four other Stark-published compositions. Not particularly distinguished, it would nevertheless sell well, and thenceforth Joplin would be known by that proud title.

That title would prove to have disadvantages, however. Despite the fact that it placed Joplin at the head of ragtime writers, not performers, there were those who viewed him much as, out West, young men looked upon well-known gunfighters. Their goal was a showdown. By the time Scott Joplin returned, the style of ragtime playing in St. Louis had changed. Gradually, the heavy march two-beat, the oom-pah of the left hand, had disappeared and been replaced by four evenly accented beats in the same interval. At the same time, right-hand play had become more complicated in its accenting. It was a speedier, more infectious type of playing, and those who were good at it viewed as inferior performers those who could not. Tom Turpin, Sam Patterson, Joe Jordan, and most of the others who frequented the district favored the faster style. Only Louis Chauvin preferred the older tempos.

A popular pastime among musicians in the district was “cutting contests,” in which two pianists vied with each other to play faster and more varied versions of the same tune. There was no quicker path to acceptance for a young newcomer than to get the best of a veteran of the district in a cutting contest. As soon as word got around that Scott Joplin was in town, many piano players were anxious to challenge him to cutting contests, and at first he complied. “Every time he sat down at the piano he played ‘Maple Leaf Rag,’” Charlie Thompson once said. Nor did Joe Jordan ever remember hearing Joplin play any but his own compositions, and Jordan remembers that Joplin played them almost exactly as they were written in sheet music form. (7) When he found that many of his listeners favored the new style and considered his style heavy and plodding, Scott refused further competition, no doubt sadly remembering the Sedalia days when he won every ragtime playing contest. Undaunted, the challengers would pretend real interest in one of his compositions and after persuading him to play it, would sit down at the piano and play their own variations of his work at lightning speed. Though men like Tom Turpin and Louis Chauvin, secure in their own talent, did not feel the need to build themselves up by breaking others down and remained his steadfast supporters, Joplin was deeply affected by these experiences. His visits to the musicians’ hangouts in the district became less frequent, and when he did appear he refused to go near the piano. Though the sporting life had never been comfortable for him and though he was happier living his quiet life composing and teaching and learning from Ernst, Joplin had been a performer for too many years not to miss playing for a crowd. But he had tremendous pride, and he would not play for people who did not understand his style.

This is not to say that Joplin fell from favor in St. Louis. He was a published composer and much respected. Most in the district stood by him. And though his rags were slower and more serious than others, many appreciated their musical value and even two-stepped to them.

There were two traditions in ragtime, the composing tradition and the performing tradition, and very few people managed to straddle the line between the two, for they required radically different temperaments. The performing tradition emphasized the moment, the one-shot improvisation, the transitory joy of an exciting variation that would never be played quite the same way again. A tradition that would reach its height in New York’s Tin Pan Alley, it was associated with all the lowlife images of the sporting district, and with some reason. That was an underground, bohemian life, an escape from the prejudices of the larger society to be sure, but in its own way a trap. It was a fast-paced life, stimulated by drink and drugs. People died of drug overdose, of syphilis—deaths in the early twenties were not uncommon for this subculture—and once you got in, you rarely had the opportunity to get out.

The other tradition, the composing tradition; was the more attractive, even to the performers. If you could write, then getting your work published was the name of the game. And if you were Black and published, you were particularly admired. Even those who delighted in “cutting” Scott Joplin would have preferred to have half his compositional talent. Jelly Roll Morton, for example, became famous for his “left-hand” piano playing, for his prowess in the new style of performance. Charlie Thompson remembers that when Jelly Roll visited St. Louis he delighted in showing off his talent. A short man, he would rear himself up to his full height as someone else played. Then, when the performance was over he would say, “Now let me show you how that piece is supposed to go.” (8) Yet Jelly Roll’s compositions were greatly influenced by Joplin’s. Louis Armstrong credited Joplin as the principal source of Jelly Roll’s ideas, and Lottie Joplin would later state, “In the early 1900s Jelly and another man named Porter King were working on a number of their own. Apparently, they got stuck. Anyway, they mailed it off to Scott, asking him to help. Later, when he completed it, Scott mailed it back, but it didn’t get published until years afterward. By then, Scott and Porter King were dead, so Jelly named it after his old friend, calling it ‘King Porter Stomp.'” (9)

Scott Joplin’s compositions had provided his ticket out of the sporting district. Teaching was far more suited to his temperament than holding his own in boisterous, smoke-filled saloons against young upstarts who could not write a note. Though he would perform on occasion, Scott Joplin’s commitment to the composing tradition was firm, and his works from then on would indicate his feelings about the proper course for ragtime—elevation to a serious musical form, not denigration to a carnival sound.

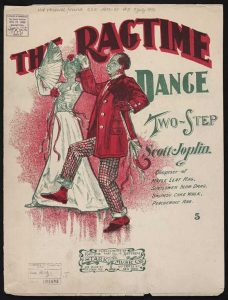

Perhaps with this in mind, and encouraged by Ernst, Scott returned to work on The Ragtime Dance, hoping that Stark would agree to publish it. The work was a source of continued dissent between the author and his publisher, and may be the reason why Joplin himself published his next work. “The Easy Winners,” issued in October 1901, bears on its cover the logo “Published by Scott Joplin, St. Louis, Mo.” and carried also the legend “Composed by Scott Joplin: King of Ragtime Writers.” As it is a fine piece, melodic and flowing, Scott Joplin was probably not forced to publish it himself. It has been suggested that Stark, being puritanical in nature, might have been loath to publish a piece that glorified sport, including horse racing (four different sports are depicted on the cover). (10) However, if this were so, Joplin could easily have sold the composition to another publisher. It is probable that Joplin chose to publish the piece himself to demonstrate independence, a subtle warning to Stark that Joplin was dependent on no one publisher.

Publication of “The Easy Winners” in October 1901 may also have been planned as a method of persuasion to get Stark to reconsider his refusal to publish The Ragtime Dance, for toward the end of 1901 Joplin presented his performance again, this time in a private hall and for the Stark family alone. Among those present was John Stark’s daughter Nell, who had recently returned from studying music in Europe. Impressed by the performance, she prevailed upon her father to publish it. (11) Pressured from several directions, Stark nevertheless remained firm in his opposition, and the rift between the two men widened.

So Joplin bypassed Stark in publishing two more compositions. In April, 1902, “I Am Thinking of My Pickaninny Days,” his first song since “A Picture of Her Face” (issued in 1895), was published by Thiebes-Stierlin Music Company of St. Louis. Written with his friend Henry Jackson, who composed the lyrics, the song was in the still popular romantic and sentimental Stephen Foster vein, and beautifully harmonized so as to appeal to a barbershop quartet type of rendition. Joplin may well have written it primarily for the money, although it reportedly did not sell very well. In May, S. Simon of St. Louis issued “Cleopha,” a “March and Two-Step” that enjoyed immediate popularity and became a favorite piece for the John Philip Sousa band.

Scott Joplin may have been quiet, rarely speaking in a voice higher than a whisper. He may have been sensitive to the sort of criticism he had borne from the “cutters.” But no one had ever called him wishy-washy. As a youngster he had been determined to make something of himself. As an adult, he was equally determined. For him, it was not enough to be published. He wanted to compose and publish an elevated type of music. And, as John Stark was learning, he could be downright ornery about it. In the meantime, Stark was probably experiencing some guilt feelings as well as concern about finances. He was aware of the importance of “Maple Leaf Rag” to the success of his business, the acquisition of a fine house for his family at 3967 Cleveland Avenue, and an excellent business plant at 306 N. Eighteenth Street. At length he consented to publish The Ragtime Dance.

With Stark’s promise secured, Joplin returned to the John Stark & Son fold, and toward the end of 1902, Stark issued two Joplin pieces, “March Majestic” and “The Strenuous Life.” The first is a fine work that marks Joplin’s coming to maturity as a composer of marches; the second is a not particularly distinguished rag. But these were hardly all of Joplin’s publications with Stark that year. Partly because his life style was now much more conducive to composing, partly because Stark had agreed to publish his dance composition, and partly, perhaps, to show his detractors that performance was not all there was to ragtime, Scott Joplin was extremely prolific that year. At the end of 1902, three more of his works were published, almost simultaneously with The Ragtime Dance, bringing the number of his works published in that single year to eight.

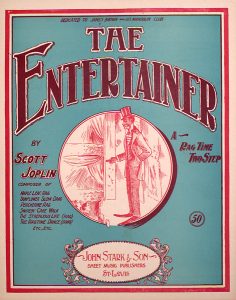

The three works were “A Breeze from Alabama,” “Elite Syncopations,” and “The Entertainer.” Of the three, the first is weakest, another march two-step, dedicated to “P. G. Lowery, World’s Challenging Colored Cornetist and Band Master.” “Elite Syncopations” is, as its title suggests, only modestly syncopated and meant to be played in the steady Joplin tempo. “Not fast,” the note over the first bar cautions, and such instructions appear over and over again in published Joplin compositions. Interestingly, they begin with the first Stark publications in St. Louis and indicate Joplin’s reaction to the new, faster style of playing he encountered in that city. From then on, in whatever terms he couched his instructions—”moderato,” “slow,” “not fast,” “not too fast”—Joplin exercised his composer’s prerogative over the mere performer.

“The Entertainer” carries these instructions (“not fast”). Some of its melodies recall the plucking of mandolins, instruments that were popular in that day, played by small groups of wandering string musicians called “serenaders”; and the rag is dedicated to “James Brown and his Mandolin Club.” Melodious, with a happy and restful quality about it, in terms of sales, the piece was the most successful of Joplin’s 1902 publications (12) and it is the best known of Joplin’s works today as a result of Joshua Rifkin’s recording and its adaptation by Marvin Hamlisch in the score of the motion picture The Sting. Its title may have come from the Sedalia period, when the Maple Leaf Club advertised Scott Joplin as “the Entertainer.” However it is unlikely that Joplin had any say in the choice of the sheet music cover, which depicts a Black in caricature, his feet fully as long as the area between his knees and his ankles—a “coon” type cover of the sort that Stark generally avoided. Not that Joplin had a mid-twentieth century type of Black consciousness: some of the words in the opening section of his piece The Ragtime Dance are embarrassing by today’s standards—references to “coon,” “razor fight,” and “dark town,” for example.

The lyrics notwithstanding, The Ragtime Dance was Joplin’s answer to the prevailing association of ragtime with lowlife. Essentially a folk ballet, it is not a denial of folkways but a presentation of them in a sympathetic, joyful light. Some of Joplin’s finest musical passages are contained in this piece, whose words give little indication of either the melody or the choreography:

Let me see you do the “rag time dance,”

Turn left and do the “cake walk prance,”

Turn the other way and do the “slow drag”—

Now take your lady to the World’s Fair

And do the “rag time dance.”

Let me see you do the “clean up dance,”

Now you do the “Jennie Cooler dance,”

Turn the other way and do the “slow drag”—

Now take your lady to the World’s Fair

And do the “rag time dance.” (13)

The entire piece filled nine printed pages and was very expensive to produce. Stark issued it reluctantly, still convinced that it would not sell well. It required more than twenty minutes to perform and was beyond the ability of the average parlor pianist. But Joplin was pleased, productive once more, and for that Stark could be thankful.

For his part, Joplin was optimistic about sales and already well into his first ragtime opera, which he had titled A Guest of Honor, news of which probably caused John Stark to groan privately. Actually, an opera by a Black man was not unheard of. Harry Lawrence Freeman, a Negro, had written The Martyr some years before, and it had been produced in Denver in 1893. (14) A Guest of Honor was one act in length and contained twelve tunes, all rags. Joplin was certain it would be popular; John Stark was not so sure.

Besides publishing more works that year than in any previous or subsequent single year, Joplin was beginning to receive more than merely local newspaper publicity. W. H. Carter, editor of the Sedalia Times, visited St. Louis in April. Some years before, he had written editorials criticizing as mere “piano-thumping” the music pouring out of the smoke-filled rooms of Main Street. By 1902, however, he had been swept up in the ragtime tide and, on his return to Sedalia from St. Louis, praised Joplin in one of his articles:

. . . Mr. Scott Joplin, who is gaining a world’s reputation as the Rag Time King. Mr. Joplin is only writing, composing and collecting his money from the different music houses in St. Louis, Chicago, New York and a number of other cities. Among his numbers that are largely in demand in the above cities are the “Maple Leaf Club” [sic], “Easy Winners,” “Rag Time Dance” and “Peacherine,” all of which are used by the leading players and orchestras. (15)

The St. Louis Fair was scheduled to open in 1903, and Tom Turpin wrote a rag in honor of the event, “St. Louis Rag.” While it was an excellent piece, unfortunately it turned out to be premature, for the opening of the fair was postponed until 1904, destroying the initial sales potential of the composition. Various people and situations were blamed for the delay, none of which caused Tom Turpin to feel any better. However, he had other reasons to be happy that year, for it was the year in which he opened what would become the most famous of the various Turpin establishments, the Rosebud Bar. (16)

Located at 2220-22 Market Street, and reportedly a multifaceted business that included gambling and prostitution upstairs, it was open “all night and day” and immediately became a favorite hangout for the best ragtime performers and for the youngsters who sought to learn from the masters. Indeed, it was advertised as a “Headquarters for Colored Professionals.” There was no question how important the piano was to Turpin. He had it on blocks about a foot high so one had to stand up to reach its keys. “He wouldn’t let just anybody play it either,” Charlie Thompson once recalled. (17) Scott Joplin was among the few who were allowed access to it, and in fact he was invited to play whenever he dropped by. In that friendly atmosphere, Joplin would indeed perform on occasion—always his own compositions and always exactly as they were written—but no one showed any disrespect, not in Tom Turpin’s place.

The Rosebud was not to be merely a saloon. Turpin quickly took steps to establish it among higher classes of society as well, and in 1902 he would inaugurate the first of many annual Rosebud Balls held in a large hall and featuring a piano contest. All the “best people in town” would attend.

In 1903, the Joplins and the Haydens moved to 2117 Lucas Avenue, where Will Joplin lived. They rented a number of rooms, some of which Belle in turn rented to visiting musicians who sought out Joplin. (18) It was a happy period for Scott. His compositions were selling respectably well, and new ideas came to him easily. Work on A Guest of Honor was progressing and he was optimistic about the future.

In February, Scott wrote to the Copyright Office in Washington, D.C., to apply for a copyright for the opera, (19) probably indicating in his letter that the manuscript copies were on their way under separate cover. Shortly thereafter he began rehearsing his drama company for a performance. The April 1903 issue of the Sedalia Times printed the following item:

Scott Hayden has been in the city all week visiting parents and friends. He has signed a contract with the Scott Joplin Drama Company of St. Louis in which Latisha Howell and Arthur Marshall are performers.

Arthur Marshall had arrived in St. Louis in 1902–3 after two years playing piano on tour with McCabe’s Minstrels. According to Marshall, (20) the opera was presented in a large dance hall in St. Louis and was quite well received—well enough to attract two of the major booking agencies in the city, Majestic and Haviland, who were interested in producing it. Joplin, of course, was also interested in the opera’s publication, and the Stark family had been invited to the performance. The Starks were fairly pleased with the opera, but according to legend felt that Joplin should write a stronger libretto. Joplin thought his book was strong enough as written.

Meanwhile, the school of ragtime known as Tin Pan Alley had arisen in New York City, primarily because New York was the center of the music publishing business but also because it was a large and busy city, demanding tempos speedier and more “nervous” than did other places. It was a commercialized style of ragtime, the style with which we in the latter twentieth century are most familiar. Also, it was primarily a ragtime played by white men, of whom composer Ben Harney was perhaps the earliest and most famous example. It was another example of whites adopting and exploiting an initially Black form. These considerations must be borne in mind when reading the following, written by a prominent Tin Pan Alley composer, Monroe H. Rosenfeld, and which appeared in the June 7, 1903, issue of the St. Louis Globe-Democrat:

St. Louis boasts of a composer of music, who despite the ebony hue of his features and a retiring disposition, has written possibly more instrumental successes than any other local composer. His name is Scott Joplin, and he is better known as “The King of Rag Time Writers” because of the many famous works in syncopated melodies which he has written. He has, however, also penned other classes of music and various local numbers of note.

Scott Joplin was reared and educated in St. Louis. His first notable success in instrumental music was the “Maple Leaf Rag” of which thousands and thousands of copies have been sold. A year or two ago Mr. John Stark, a publisher of this city and father of Miss Eleanor Stark, the well known piano virtuoso, bought the manuscript of “Maple Leaf” from Joplin. Almost within a month from the date of its issue this quaint creation became a byword with musicians and within another half a twelfth-month, circulated itself throughout the nation in vast numbers. This composition was speedily followed by others of a like character. Until now the Stark list embraces nearly a score of the Joplin effusions . . .

Probably the best and most euphonious of his latter day compositions is “The Entertainer.” It is a jingling work of a very original character, embracing various strains of a retentive character which set the foot in spontaneous action and leave an indelible imprint on the tympanum . . .

Rosenfeld’s factual errors regarding Joplin’s birthplace, the year “Maple Leaf Rag” was published and the early success of the piece notwithstanding, (21) this is a remarkable tribute to a Black composer of classical ragtime from a white composer of “pop” ragtime. Men like Rosenfeld were publishing rags that sold far better than most of Joplin’s; in addition, they were schooled in a radically different style of performance. And yet, a discerning man like Rosenfeld could see Joplin’s brilliance and praise it publicly. The Rosenfeld article continues:

Joplin’s ambition is to shine in other spheres. He affirms that it is only a pastime for him to compose syncopated music and he longs for more arduous work. To this end he is assiduously toiling upon an opera, nearly a score of the numbers of which he has already composed and which he hopes to give an early production [in] this city.

It is clear that Joplin sorely wanted to establish a reputation as a composer of operas and ballets, of serious works—not the simple rags he effortlessly dashed off. But as 1903 wore on, it appeared that such a reputation would not be established through the sales of his works. The Ragtime Dance was selling poorly, as John Stark had expected it would. The two still had not come to an agreement on A Guest of Honor. Once again a rift developed between the idealistic composer and the business-minded publisher.

Again Scott Joplin decided to show John Stark that he didn’t need the company as much as the company needed him. All four of the Joplin pieces published in 1903 were issued by other publishers. The Val A. Reis Music Company of St. Louis brought out ‘Weeping Willow” and a second Joplin-Hayden collaboration, “Something Doing.” Victor Kremer of Chicago published “Palm Leaf Rag,” and Success Music Company, also of Chicago, issued a song, “Little Black Baby.” (22)

The first three works are unmistakably in the Joplin tradition, and all are very songlike, perhaps indicating his concentration on his opera at the time. Both “Weeping Willow” and “Palm Leaf Rag” have about them a “plantation melody” aura that is especially evident in “Weeping Willow,” which Trebor Jay Tichenor, for one, considers one of his most moving creations. Deceptively light in format, it has about it a dark and introspective air. Thus, the title is very descriptive. (23) “Something Doing,” the second collaboration between Joplin and Hayden, has given rise to controversy over which composer contributed what elements. It is a smoothly flowing, rhythmic, and melodious piece, clearly a whole, not a collection of parts. Although no mention is made of Joplin’s earlier works on the cover, the cover illustration contains elements clearly borrowed from the first cover of “Maple Leaf Rag.” A Negro couple, dressed in their finery and on their way to a cakewalk, are depicted in almost the same position, but reversed as in a mirror image, as one of the couples on the “Maple Leaf Rag” cover, and the decorations on the man’s sleeve and on the hook of his cane are similar. The “Something Doing” cover, however, depicts a gallery of well-to-do white people ogling (some using opera glasses) the couple and acting thoroughly amused. A “coon cover” of the more genteel sort, to be sure, but a “coon cover” nevertheless.

“Little Black Baby” is best forgotten. Clearly a potboiler, it may have been done by Joplin as a favor to Louise Armstrong Bristol, who wrote the words and copyrighted it. Joplin’s name does not even appear on the cover, an omission he may have insisted on. The publisher, Success Music Company, was a vanity press, and indeed no other publisher but a vanity press would likely have accepted it. A sample of the lyrics: “What says dis little black baby to little black mammy by its side? Goo-goo-goo-e, goo-garee-goo; Tra-la-la-ra-ba-ma-oo.” Somewhat puzzling is that the cover illustration is of a white baby. Joplin’s melody is fittingly trite.

It is interesting to speculate that Joplin may have collaborated on the song to earn some extra money for the care of his own baby, for probably sometime in early 1903 a baby daughter was born to Scott Joplin and Belle Hayden. (24)

Both parents greeted the event with hope that the child would bring them closer together. They had not been getting along very well. To get along with Scott Joplin, a woman either had to share his consuming interest in music or understand him enough to nurture him in his interest and not to resent it. Belle apparently did neither. Scott spent long hours shut up in his study, composing at his oak rolltop desk and at his beloved piano, leaving her alone for extended periods of time; and perhaps when he did have time to give her the attention she sorely required she complained to him and forced him away. Not to put the blame entirely on Belle, Joplin appears to have been very critical of her lack of musical talent, although he must have been aware of it from the start. He may have been a very demanding genius. If the birth of their daughter was a source of hope for an improved relationship, that hope was soon dashed. Ill from birth, the little girl lived only a few months, and with her death all hope for the Joplins’ relationship seems to have died too. Arthur Marshall’s stated recollection of the situation is a sensitive and tactful one:

Mrs. Joplin wasn’t so interested in music and her taking violin lessons from Scott was a perfect failure. Mr. Joplin was seriously humiliated. Of course unpleasant attitudes and lack of home interests occurred between them.

They finally separated. He told me his wife had no interest in his music career. Otherwise Mrs. Joplin was very pleasant to his friends and especially to we home boys. But the other side was strictly theirs. To other acquaintances of the family other than I and Hayden and also my brother Lee who knew the facts, Scott was towards her in their presence very pleasing. A shield of honor toward her existed and for the child. As my brother . . . Hayden and I were like his brothers, Joplin often asked us to console Mrs. Joplin—perhaps she would reconsider. But she remained neutral. She never was harsh with us, but we just couldn’t get her to see the point. So a separation finally resulted. (25)

Probably the Joplins parted in the late summer or early fall of 1903. He moved out of the house on Lucas Avenue and to a room in the house where the Turpins lived, but he would not stay there long. The past few months had been fraught with tension and unhappiness. St. Louis held unpleasant memories for him, and before long he would leave the city.