5 Chapter V: On the Move Again

In the fall of 1903, Scott took his drama company, renamed the Scott Joplin Ragtime Opera Company, on tour with A Guest of Honor. His first extended period of traveling in some years, the tour took him to Iowa and possibly to Nebraska, as well as to other parts of Missouri. (1) At first, Joplin enjoyed being on the road again. He was greeted as a celebrity in red-light districts and honky-tonks wherever he went, and in the cities and towns far away from St. Louis once again he felt free to go to the taverns and saloons and play his compositions without feeling self-conscious. But within a month the tour was beset by difficulties. There was dissension among the twelve members of the company and by the time they had played their way through Missouri and reached Iowa, the troupe was in serious trouble.

Were there disagreements between Joplin and the members of his company over A Guest of Honor or was the dissension merely a result of conflicting personalities? We will probably never know. We do know that the opera company disbanded and at least five members took leave of the rest. With the remaining members Joplin quickly formed a minstrel show, the cast probably pooling their talents and material remembered from other shows in which they had performed. However, this makeshift minstrel show was not successful either. Items in the “Correspondence” section of the New York Dramatic Mirror in September and October 1903 graphically tell the story:

- September 12, 1903 –

- Missouri, Webb City—New Blake Theatre: Scott Joplin Ragtime Opera Co.

- October 17, 1903 –

- Iowa, Ottumwa—Grand Opera House: Joplin Opera Co. – Sept. 29 failed to appear; reported disbanded

- Mason City—Parker’s Opera House: Scott Joplin Opera Co. 12

- Nebraska, Fremont—New Larson: Joplin Ragtime Minstrels 7

- Beatrice—Paddock Opera House: Scott Joplin’s Ragtime Minstrels 6

- October 24, 1903 –

- Iowa, Mason City—Wilson Theatre: Scott Joplin Opera Co. 12 canceled

- Nebraska, Fremont—Love’s Theatre: Joplin Minstrels 7 canceled.

The failure of the tour must have been a heavy blow for Joplin, but if he had any apprehensions about returning to St. Louis, they were dispelled when he arrived back in the city. Perhaps having heard of the abortive tour and wishing to show their support, the people of the district welcomed him with a parade along Market Street. Thereafter, every time he returned to St. Louis he was greeted with such a parade. (2)

In late 1903 or early 1904, Joplin returned to Sedalia, taking a room at 124 West Cooper and listing himself in the 1904 city directory under “music.” He had known happy times in Sedalia and perhaps he felt the need to return there for that reason. He would visit St. Louis from time to time, but he did not return for Tom Turpin’s third annual Rosebud Ball and piano-playing contest. The absence of his name is noticeable in the following account of the event that appeared in the February 27, 1904, issue of the St. Louis Palladium:

On Tuesday last the Rose Bud club gave its third annual ball and piano contest at the New Douglass hall . . . and it was one of the largest, finest and best-conducted affairs of the kind ever held in St. Louis. The hall was packed and jammed, many being unable to gain admission, and the crowd was composed, well-dressed, good-looking and orderly people, from all classes of society. A great many of the best people in town were present, among them being The Palladium man, to enjoy the festivities and witness the great piano contest.

Mr. Tom Turpin presented an elegant gold medal to the successful contestant, Mr. Louis Chauvin. Messrs. Joe Jordan and Charles Warfield were a tie for second place . . . The club desires to thank their many friends for their generous support, and promises on the occasion of their next annual ball to see to it that every piano player of note in the United States enters, and will give an elegant diamond medal to the winner . . . Mr. Samuel Patterson came from Chicago just to attend the Turpin ball. (3)

By the time Scott returned to St. Louis, John Stark was looking more favorably on A Guest of Honor. Whether this change of heart involved his desire not to lose Joplin’s friendship or business is not known; certainly it was not because of the abortive tour. Plans to publish the work went ahead, and despite the fact that their initial five-year contract was up, Joplin would publish two excellent rags with John Stark & Son. Two other pieces published that year were issued by other firms. One was “The Favorite,” the rag that was sold to A. W. Perry & Sons back in 1899 and whose publication Joplin may have requested delayed until his contract with Stark was completed. (4) The other was “The Sycamore,” published by Will Rossiter in Chicago, where Joplin probably visited while on tour with his opera company. Billed as “A Concert Rag,” it indicates Joplin’s increasingly ambitious attitude toward ragtime and has been described by some as a “ragtime etude.”

The St. Louis Fair finally opened on April 30, 1904. Huge, lavish, it was eagerly greeted by the district, for the out-of-towners would bring many dollars to spend there when they came to the fair. Come they did. From its opening at the end of April to the closing on December 1, an average of more than 100,000 new visitors came each day, and of course many visited again and again. It was a fascinating exhibition, including the largest number of foreign exhibits of any fair to date. Electric lights were everywhere—an exciting new invention—and one hundred automobiles were on display, one of which had actually made the trip from New York to St. Louis “on its own power.” (5)

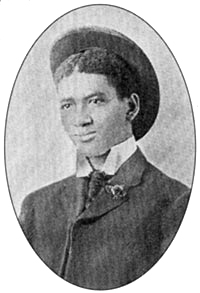

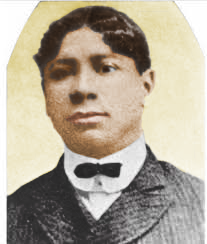

One of the major attractions of the fair was the Cascades Gardens, a huge watercourse of falls and fountains, ponds and lagoons that flowed down the main thoroughfare. Capitalizing on and memorializing the fair’s main attraction, Joplin wrote “The Cascades” and caught in it the bubble and flow of the watercourse. It was billed as “The Masterpiece of Scott Joplin,” an accolade that Joplin probably liked. Evidently, he also liked the photograph of himself that appeared in an oval frame on the cover of the first edition of the sheet music, for he used the same photograph on a rag published by another company five years later.

One of Stark’s advertisements for “The Cascades” poked fun at those who deplored ragtime without understanding it:

A FIERCE TRAGEDY IN ONE ACT

SCENE: A Fashionable Theatre. Enter Mrs. Van Clausenberg and party—late, of course.

MRS. VAN C: “What is the orchestra playing? It is the grandest thing I have ever heard. It is positively inspiring.”

YOUNG AMERICA (in the seat behind): “Why that is the ‘Cascades’ by Joplin.”

MRS. VAN C: “Well, that is one on me. I thought I had heard all of the great music, but this is the most thrilling piece I have ever heard. I suppose Joplin is a Pole who was educated in Paris.”

YOUNG AM.: “Not so you could notice it. He’s a young Negro from Texarkana, and the piece they are playing is a rag.”

Sensation—Perturbation—Trepidation—and Seven Other Kinds of Emotion.

MRS. VAN C: “…. The idea. The very word ragtime rasps my finer sensibilities. (Rising) I’m going home and I’ll never come to this theatre again. I just can’t stand trashy music.” (6)

Stark is understandably laudatory, but he is not alone. In the opinion of many musicologists, “The Cascades” is one of the peaks of classic ragtime, one of the best of Joplin’s works. Its happy, swinging elements show Joplin’s rare ability to adapt the folk rhythms and moods that are the source of ragtime in a continually creative and refined manner. Most other rag composers at this time had stalled in a rote formula and were simply “ragging” already established forms. Joplin was constantly developing the possibilities of ragtime and improving his compositional abilities through study, on his own and with Ernst. Among his personal effects when he died was a well-thumbed and marginally notated copy of A Manual of Simple, Double, Triple, and Quadruple Counterpoint. (7)

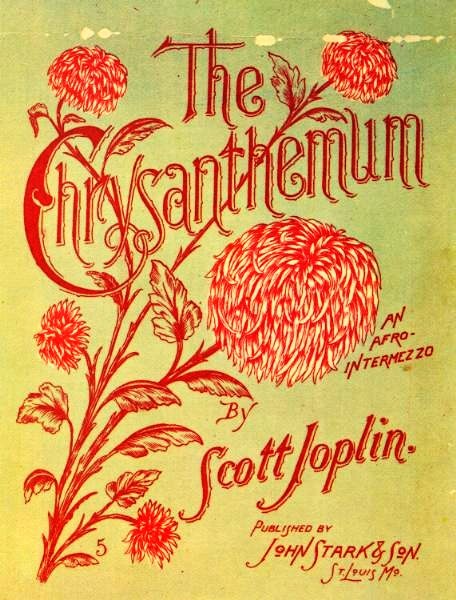

“The Chrysanthemum,” the other work published by Stark in 1904, shows Joplin’s continued search, aided by Alfred Ernst, into the classical possibilities of rag. Subtitled “An Afro-Intermezzo,” it has no discernible African elements in it other than those out of which the bases of ragtime developed. Marked “Fine” with a firm, final chord, it represents a further exploration into classical form and has a minimum of syncopation. Like many of Joplin’s works, however, it has a deep, introspective quality. Indeed, Stark advertised that Joplin wrote the composition as a result of a dream he had after reading Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, and the fantasy-aura about it lends credence to this legend. (8)

Sometime in late 1904–early 1905, Stark moved his family to 4500 Shenandoah Street in St. Louis and established his business in the city. He is listed in the 1905 City Directory as President, Music Printing and Publishing Company. Largely due to Scott Joplin, Stark was becoming highly successful. For his part, Joplin may have felt that Stark owed him more serious consideration of A Guest of Honor for publication, given his relative loyalty to the publisher. It appears that they were disagreeing again, for Stark published only one of the Joplin works is sued in 1905. Called “Rosebud Two-Step,” and dedicated to “my friend Tom Turpin,” it is a gay march in the typical two-step pattern and destined for some fame not so much because of its tune as because of its name.

Of the six works Joplin published that year, four are named for women. Only once before, in 1902, had he published a composition with a woman’s name—”Cleopha.” And only one more would be so named after “Antoinette,” published in 1906. “Bethena” is a waltz, and one of the finest Joplin ever published. Subtitled “A Concert Waltz,” it is perhaps the first true ragtime waltz ever written. An enchanting, almost haunting melody, its mood is heightened by the photograph of a beautiful Black girl on the cover. Who was Bethena? Perhaps she was just a beautiful girl whose photograph was chosen by the T. Bahnsen Piano Manufacturing Company, which published the work. The same company published the other Joplin waltz to be issued that year, “Binks’ Waltz,” which has little in the way of comparison with “Bethena.” A pleasant waltz in the polite Victorian style, it seems to have been written for children, with which its cover is illustrated. The same company published the Joplin song of that year, “Sarah Dear,” with words written by Joplin’s friend and member of the Scott Joplin Drama Company, Herny Jackson. It is not an entirely original tune. The chorus is the same tune used in the Ben Harney rag “St. Louis Tickle.” But the tune wasn’t original to Harney either, for it had long been in use as a riverboat drinking song.

Will Rossiter, a Chicago firm that had published Joplin before, issued “Eugenia” that year. The first page of the composition contains the blurb: “Notice! Don’t play this piece fast, It is never right to play ‘Ragtime’ fast. Author.” Clearly, Joplin was becoming increasingly concerned with what he considered the adulteration of ragtime by those who emphasized speed over form. Clearly also, he was not yet comfortable with the term ragtime, setting it off by quotation marks as if he still considered it a colloquialism. “Eugenia” is an involved piece of writing, done specifically, as the cover says, “for Band and Orchestra.” Some musicologists hail it as the first of the mature Joplin pieces; others bemoan its lack of spontaneity. (9)

The final piece bearing a woman’s name is “Leola,” issued by a new publisher for Joplin, American Music Syndicate of St. Louis. This, too, carries the warning not to play it fast. Like “Eugenia,” is seems to indicate a Joplin striving for form over spontaneity, but it is not as successful as “Eugenia.” Although it is the first Joplin piece to have been copyrighted simultaneously in Britain, (10) it did not sell particularly well and indeed did not come to light until the 1950s. What makes it an interesting document is its possible biographical importance, for despite its dedication to “Miss Minnie Wade,” the composition is likely named for a woman with whom Joplin was in love. Ragtimer Charlie Thompson once said “Joplin’s one love was a girl named Leola who jilted him! For sometime afterward he was not interested in women.” (11) Were Bethena and Eugenia, and, later, Antoinette real women too? We may never know.

It would seem that Scott Joplin was rather unlucky with women in that period of his life. By contrast, he attracted young musicians who, having met him, and even before actually making his acquaintance, idolized him and were forever loyal to him. In that year a nineteen-year-old named James Scott came briefly into his life. Scott had been born in Neosho, Missouri, in 1886, and had moved with his parents first to Ottawa, Kansas, and then to Carthage, Missouri, where his father purchased his first piano for him. When he was sixteen, he went to work for Dumars music store, washing windows. When the owner learned that he could read and play music, James was put to work plugging the latest tunes. He had a natural talent for composition, and his first work, “A Summer Breeze—March and Two Step,” was published by Dumars in early 1903, when he was just seventeen years old. By 1904 two more compositions sold respectably in the area, but not enough to constitute a going business. Dumars ceased publishing, and Scott set off for St. Louis to find a new publishing company.

One of his favorite pieces, and one that had often inspired him, was “Maple Leaf Rag.” Finding himself in St. Louis, and learning that Scott Joplin was in town for a visit, he located the master and asked him to listen to his work. Flattered by the youth’s attention and always interested in young talent, Joplin listened to Scott’s rag and, recognizing merit in it, introduced the youth to John Stark and recommended that Stark purchase the work. Stark published it the next year as “Frog Legs Rag.” Joplin had little way of knowing that the young man he had helped would later become one of the only two composers considered on the same level as he was—indeed, second only to him. (12)

For his own part, Scott Joplin seems to have entered a very nonproductive period toward the end of 1905. Perhaps his having been jilted by Leola affected him; perhaps he was simply “written out” after having produced a number of fine pieces. Whatever the reason, he apparently decided it was time to hit the road again, and sometime late in 1905 he set out for Chicago, where Arthur Marshall was living with his bride and playing at Lewis’s Saloon (13) and where Louis Chauvin had become firmly and fatally ensconced in that city’s red-light district.

Scott stayed with Marshall while he rather half-heartedly made the rounds of the music publishers. (14) It is likely that he did not have a substantial amount of material to offer, and he seems to have been primarily interested in making contacts, in case he decided to remain in Chicago. Making his way to the city’s red-light district, he met with Louis Chauvin, an experience that was not likely to have increased his optimism about the lot of a Black ragtime composer. The brilliant young composer pianist who had won the piano contest at Tom Turpin’s Rosebud Ball back in February 1904 was only twenty-two, but it was tragically evident that he would not live to be thirty. Like too many other young members of the musical subculture, he had become addicted to drugs and had contracted syphilis. He and Sam Patterson were still together, the more stable Patterson concerned about his friend but powerless to help him.

Chauvin smoked opium constantly and was already showing signs of the terminal syphilis that would eventually kill him in 1908, but he continued to compose, creating the most exquisite themes at times. Unfortunately, he remained too undisciplined to incorporate these themes into a finished, and publishable, work.

Thanks to Scott Joplin, at least some of those themes were eventually published in “Heliotrope Bouquet—A Slow Drag Two-Step.” When Joplin visited Chauvin in a bawdyhouse parlor, he was shocked at the young man’s appearance and physical condition, but he had seen such things before and knew there was little he could do. He inquired about Chauvin’s composing and was promptly treated to a rendition of two beautiful themes. Perhaps aware that the best thing he could do for his young friend was to get those themes published, he promptly sat down at the parlor piano and composed two themes of his own. Sam Patterson, who witnessed the event, marveled at Joplin’s ability to work out two complementary themes on the spur of the moment. (15) Joplin and Chauvin worked together a while longer, smoothing over the rough places, but it was Joplin who did the final polishing, Chauvin’s mood being too fitful to permit extended concentration on any one thing even if it was to be one of the few published works to bear his name.

During his stay in Chicago, Joplin also worked on a collaborative piece with Arthur Marshall. In this piece, too, the work of Joplin’s collaborator came first, in the two beginning strains, while the trio and final strain were Joplin’s. It attested to Joplin’s genius and to his generosity that he allowed his protégés to set the tone of the piece in his collaborations with them, and composed material that complemented theirs. The Joplin-Marshall collaboration, “Lily Queen—A Ragtime Two-Step,” would be published in 1907, the same year that “Heliotrope Bouquet—A Slow Drag Two-Step” would be issued.

After staying with Marshall for a few weeks, Scott found a place of his own at 2840 Armour Avenue and listed himself as a musician in the 1906 city directory. But he did not stay in Chicago long. According to Arthur Marshall, he was very eager to go to New York. (16) John Stark had just moved there, establishing his publishing business at 127 East Twenty-third Street. New York was undeniably the center of the music publishing business in the United States, and Scott, now that he had no real ties in the Midwest, was eager to try his own luck there. He did not go immediately to New York, however. Psychologically, he was not prepared for such a major move. While maintaining contact with Stark, he returned to St. Louis, using the Turpin place as a base while he toured the area vaudeville circuit. (17)

Too disturbed mentally to compose very much, and too unsettled to make a living teaching music, he succumbed to performing again. At times, he enjoyed it, especially going out to Clayton, Missouri, with newspaperman Harry La Mertha, with whom he collaborated on a potboiler song called “Snoring Sampson.”

It was a time of rather aimless wandering for Scott, and perhaps in an attempt to re-establish his equilibrium he returned to his roots. Sometime in 1907 he went back to Texarkana, the first time he had been home in several years. (18)

Sadly, his mother was not alive to see him. Florence Joplin had died some years earlier, in her early sixties. (19) A strong, determined woman, Florence had managed to support herself to the end. A few years after Scott had left Texarkana, Canaan Baptist Church had moved from the old Hide house into its own building on Laurel between Eighth and Ninth Streets. (20) Florence had become caretaker of that church, performing a variety of functions. She scrubbed the floors and kept the lamps filled with oil. “She was a little bitty woman, couldn’t have weighed more than ninety pounds,” recalls George Mosley. “I’d often go down and get the lamps off the wall for her and put oil in them so she wouldn’t have to do it.” Florence also rang the church bell, which was employed to announce church services or otherwise to call the congregation together, and to report deaths in the community. “That old lady rang the bell whenever somebody died,” says Mosley. “If it was midnight and she got the word, she tolled that bell. And she had a way of tolling it that would tell you whether it was a child or an old person, or a middle-aged person. The way she tolled that bell . . .” (21)

Florence had lived to see all her children grow up. Monroe, who had gone to live with his father and Laura before Scott left to go on the road, had married and had two children, Mattie and Fred, by his first wife, who had subsequently died. Later, around 1900–1, he had married his second wife, Rosa, by whom he’d had two more children, Donita and Ethel. Robert had married a woman named Cora and had a daughter, Essie, (22) but the marriage had failed, and around 1901 he had left Texarkana to join his brothers Scott and Will in St. Louis. Both Osie and Myrtle had worked as cooks and sung in and around the area before marrying and moving into Arkansas. (23) While only Scott had achieved any renown, none of Florence’s children had died or been imprisoned, and all had learned trades of some sort, in itself a source of pride for a Black mother in Texas at the turn of the century.

Scott’s father, Jiles, was still very much alive, although he no longer worked for the railroad. Swinging the huge mauls to pound spikes into the tracks, dragging the heavy sections of track, and heaving them into place had been tough, backbreaking work. Indeed, the average working life of a railroad laborer was between ten and fifteen years. Jiles had developed leg trouble, and though he had still listed himself in the 1906 Texarkana City Directory as a laborer, he had done little heavy labor for some years. Now, at the age of sixty-four, he hobbled around on a stick and did yard work when he felt up to it. (24)

Some years earlier, he and Laura had separated. (25) Zenobia Campbell recalled, “The boarding house lady [at 830 Laurel Street] tried to get him and his second wife back together, but it didn’t do any good. They never did live together anymore.” (26) When Scott returned to Texarkana in 1907, Jiles was living with Monroe and Rosa at 815 Ash Street, and during his visit Scott, too, stayed with his older brother and family.

Scott’s visit was one of the most exciting events the family could remember. Not only was he a famous composer of music, but he was a brother and son who had traveled, who had been to the big cities of St. Louis and Chicago, met famous and interesting people, and, not least, seen his two brothers, Robert and Will, neither of whom had evidently been home in some years. “They kept him up all day till late at night,” recalls Scott’s nephew, Fred. (27)

Scott’s return was also a major event in the life of the Texarkana Black community, and an occurrence of some interest to the white community as well, for Scott was a ”home boy” who had made good, the composer of piano pieces that were played on parlor pianos and performed by itinerant pianists across the country. Scott was aware of his position as a returning hero and exploited it for what he could. As George Mosley puts it, ‘Well, he did act kind of famous.” Soon after Scott’s arrival, he went down to the Beasley Music Store and began to play some of his compositions on the piano in the back room of the store, attracting passers-by, and word quickly spread that not only was Scott Joplin back in town, but also he was playing his famous music. They gathered around him and questioned him about his life, openly admiring. “When they came home, it was after midnight,” Fred Joplin recalls. It was an exhilarating experience for Scott, and though it was late, he sat right down at the Joplins’ parlor piano and continued playing. “He was playing,” says Fred Joplin, “I heard the music and I got out of bed and just sat there, listening.” (28)

Fred Joplin remembers something else, although his memory is hazy. During an interview in 1976 he said that by the time Scott returned to Texarkana around 1907 he had been to Germany. “He was playing somewhere and a German got in with him and when he [the German] went back to Germany he carried Scott back with him. . . . So he went over there, and I don’t know how long he stayed. But when he did come back, he had played so much and wrote a lot of music and he had started his fame.” Although none of the other Texarkanans interviewed could recall any mention of a German or a trip to Germany by Scott, these statements of Fred Joplin’s are intriguing. The possibility that Scott did visit Europe continues to be a viable one, and hopefully someday someone will be able to document it.

The days were filled with music. Mattie, Monroe’s eldest daughter, was studying music, and Scott taught her to play “Maple Leaf Rag” on the parlor piano. (29) And he played at least once at one of the weekly dances held at J. C. Johnson’s pavilion down on Ninth Street. (30) Perhaps one of the most gratifying aspects of Scott’s visit was being able to show his old teacher and mentor that he had made good. Johnson was a classicist and it is likely that he did not entirely approve of Scott’s ragtime compositions, but he would have understood and encouraged his former pupil’s urge to create ragtime opera. Perhaps Scott played excerpts from The Ragtime Dance and A Guest of Honor for Johnson.

Scott stayed only a few days in Texarkana before he was off again, to return no more. He left behind him warm feelings and happy memories, and the seed of a small amount of family dissension, for his uncle’s visit had caused Fred Joplin to decide he wanted to be a piano player too. “I wanted to play like my uncle. That’s what started me wanting to play, was seeing him. So I started banging on the piano, and in six years I had learned it so good that I played for all the commencement exercises. But my aunties, who were school teachers, they wanted me to be a doctor. ‘We don’t want no piano player,’ they said.” (31) Fred says that the family did not talk about Scott much after he left; perhaps they did not want to encourage Fred.

Scott returned to the Midwest and eventually settled for a time in St. Louis. His spirits lifted somewhat after his visit with his family, but his productive spark was missing still. In terms of published compositions, the year 1906 was the leanest of Joplin’s career so far. Only two works were issued, both by Stark from his New York office, and one, The Ragtime Dance, was a condensed piano version of the original, a version no doubt intended to recoup some of the losses the Stark concern had sustained as a result of publishing the full-length work. Even the second work, “Antoinette,” a conventional 6/8 march, appears stylistically to have been written a year or two before or even earlier. It was a bad time for Joplin, who must have wondered if his compositional ability had left him completely. Why else would he have listed himself in the 1907 St. Louis directory as a laborer?

Yet Scott Joplin soon rose out of his melancholy. The impetus may well have been a trip to New York. White composer Joseph Lamb, ranked in music history with Joplin and James Scott as one of the three “greats” of ragtime, recalls that his first meeting with Joplin occurred in the offices of the Stark Publishing Company at 127 East Twenty-third Street in Manhattan. Lamb was a young, struggling composer who had tried to sell two rags to the Starks, both of which had been rejected. Nevertheless, he was one of the best customers of their sheet music business. He bought so many rags from them that he had a standard discount. On the happy day in 1907 that he met Joplin, he did not recognize the Black man sitting in the store talking with Mrs. Stark. Lamb would hardly have noticed him at all if the man had not sported a bandaged foot and a cane. Lamb told Mrs. Stark that he liked the rags of Scott Joplin best and wanted to buy any he did not already have. The stranger spoke up, naming several pieces and asking if Lamb had them. Lamb bought those he did not already own, thanking the stranger for his help. Scott made no attempt to identify himself. As he was leaving, Lamb commented that Scott Joplin was one composer he would like to meet.

“Really,” said Mrs. Stark. “Well, here’s your man.”

Scott learned of Lamb’s own attempts to get his rags published and hobbled beside the younger man as they walked along Twenty-third Street. They sat on a bench in Madison Square and talked about the music business. At length, Scott invited the young white man to his home. Eagerly, Lamb went to the boardinghouse where Joplin was staying. When he entered a room filled with Blacks, he must have felt some trepidation about his ability to compose works in a musical genre that was identified primarily with Blacks. Once he started playing, his fears subsided. Those around him stopped talking to one another and listened; then they approached the piano to watch him. He was playing “Sensation—A Rag,” and when he was finished, Joplin paid him a high compliment. “That’s a good rag,” Scott said, “a regular Negro rag.” He offered to present the piece to Stark personally, and to lend his name as arranger (a title which in those days often referred to the one who had arranged to have a piece published).

A week later, Stark offered to buy the piece for twenty-five dollars, with the pledge of another twenty-five dollars after the first printing of one thousand copies was sold. Lamb eagerly accepted and, thanks in large measure to the interest and help of Scott Joplin, the career of Joseph Lamb was launched. (32)

Scott’s own career took a decided upturn that year. His creative spark returned, perhaps simply because of the stimulus of the New York environment. Like so many other out-of-towners before and after him, Joplin was awed by New York, and like other newly arrived Blacks he was astonished at the city’s large Black population, which was growing rapidly in that first decade of the twentieth century. Between 1890 and 1910, the Black population of New York nearly tripled, and Manhattan received the greatest influx. The majority were from the southern coastal states, and they grouped together, partly out of choice and partly because of residential segregation, in areas like the Tenderloin, Twenty-fourth to Forty-second Streets from Fifth Avenue westward, and Hell’s Kitchen. They were mostly poor, mostly young, and mostly unskilled, but there was a largeness about New York and an energy that made anything seem possible, at least for a time.

Eight compositions were published under Joplin’s name that year, 1907; two songs, two collaborative works, and four individual pieces. In all probability, the songs were mere potboilers: “Snoring Sampson,” with words by Scott’s St. Louis newspaper friend Harry La Mertha, and “When Your Hair Is Like the Snow,” with lyrics by a man who called himself Owen Spendthrift. Joplin may well have done the music for them in order to earn money to finance his trip from Chicago to New York. Of the two, “Snoring Sampson” is the more interesting. Its “coon cover” depicts a huge-lipped, prickly-headed man snoring loudly while his wife, sporting pickaninny braids that radiate from her head, watches him with extreme displeasure. Subtitled “A Quarrel in Ragtime,” the song also has “coon lyrics”:

“Samuel Sampson was a coon with a basso voice . . . I tells you that I loves you and I hate to squeal but, I information you this bed’s no automobile . . .”

Joplin’s arrangement, however, contained a number of original ideas, and his employment of them in the song makes it better musically than the run-of-the-mill ragtime song of the period. Perhaps because of his friendship with La Mertha, Joplin put more effort into the music for this song than he did for the other songs on which he collaborated.

Of the collaborative instrumental works, one was “Heliotrope Bouquet,” which Joplin had worked on in Chicago with Louis Chauvin. Sadly, Chauvin was not around to reap the financial or artistic benefits of the collaboration; he died shortly after “Heliotrope Bouquet” was issued. The other collaborative work, “Lily Queen,” written with Arthur Marshall while Joplin was in Chicago, appears to contain some Chauvin-like elements (in the third strain) as well. While not as successful artistically as the Joplin-Chauvin collaboration, it is nevertheless a graceful and harmonious work. The Stark Company published “Heliotrope Bouquet,” but a new publisher, W. W. Stuart, 48 West Twenty-eighth Street, New York, issued “Lily Queen.” Whether Stark rejected the Marshall-Joplin collaboration, or whether Joplin deliberately sought out a new publisher for the piece is not known.

It is likely that Joplin was searching for new publishers. They abounded in New York, and some were interested in publishing works by “The King of Ragtime.” Of the four compositions written alone by Joplin issued in 1907, only one was published by Stark, and it is the one of the four that is nearest in style to Joplin’s Sedalia-St. Louis period works. “Nonpareil,” in fact, might have been written earlier and held by Stark for a year or two before being issued. If so, then Scott did indeed strive toward independence once he arrived in the East.

Two of the 1907 works were published by Jos. W. Stern & Company, 102–104 West Thirty-eighth Street, New York. “Searchlight Rag” was clearly named in honor of the Turpin brothers, who had tried their hand at gold mining in Searchlight, Nevada, years before; its rolling bass calls to mind the rough-and-tumble life of the frontier prospector. The other, “Gladiolus Rag,” is true Joplin in its floral title and in its perfect unity. Artistically, it is one of Joplin’s most successful rags.

The final individual work published in 1907 was “Rose Leaf Rag,” and with “Searchlight Rag” and “Gladiolus Rag” it signals a new stage in Joplin’s development and a new meaning for the term “classic rag.” In these compositions, ragtime reaches its maturity and becomes not an amalgamation of elements but a unified and highly individual form. Stylistically, there is little question that Joplin composed these works while in New York, or at least after he had left St. Louis. They represent a new era in his career.

“Rose Leaf Rag” was issued by a Boston publisher, Joseph Daly. Scott was moving around a lot at that time. Though he regarded New York as his base, he traveled extensively and did not list himself in the New York City directories. Under the billing “King of Ragtime Composers—Author of Maple Leaf Rag,” he toured the East Coast during the next few years, and even ventured back into the Midwest, if Jess Williams’ recollection is at all accurate.

Williams, an eighty-four-year-old pianist from Lincoln, Nebraska, recalled in 1976 that he was in a musician’s clubroom in Lincoln one summer day when a man walked in and identified himself as Scott Joplin. One of the people in the room expressed disbelief, and so to prove his identity Joplin sat down at the piano and played “Maple Leaf Rag” so well that before he was finished everyone in the room knew it had to be the master himself. Joplin, Williams recalls, was in Lincoln to place copies of his rags in the town’s music shops on a consignment basis. The teen-age Williams immediately attached himself to Scott, not just because the man was famous and an excellent piano player but because he was attracted to him personally. “You felt as though you could put your trust in him,” Williams remembers. Joplin shortly left Lincoln, but he went away leaving Williams with a precious memory and a greater piano-playing repertoire, having taught him the “walking bass” that he has used in his piano playing ever since. (33)

During his travels, Scott visited Washington, D.C., where he met Eubie Blake. A native of Baltimore, Blake was then in his mid-twenties and already a veteran ragtime pianist. He had started playing in the Baltimore red-light district at the age of fifteen, sneaking out of his home at night so his mother, who disapproved of ragtime, would not find out. In his late teens he had gone to Washington’s substantial red-light district and was firmly ensconced there by the time he met Scott Joplin. “I met Scott Joplin in 1907, ’08 or ’09,” Blake recalled on the occasion of the presentation of Treemonisha at Wolf Trap Farm. “I can’t remember just which year—oh my, there goes my memory—I met him right here in Washington. He was very ill then and I didn’t get to see his greatness, but I remember there was a party for both of us at a colored cabaret.” (34)

There Scott also met Lottie Stokes, age thirty-three and five years his junior. Being a spinster, she would not have attracted the average itinerant pianist, but Scott Joplin was not the average itinerant pianist. He was not looking for a passionate love affair; he’d had that and was the worse for it. He was looking for stability, for peace, and for a mature woman who could provide it. Lottie Stokes was that kind of woman. They were married, (35) and Lottie accompanied him in his travels, which now seemed to take on added meaning. They were tours now, not somewhat aimless wanderings. Though the two were often penniless, Lottie was committed to and supportive of Scott. At peace and happy with the love the need for which is infused in so many of his compositions, Scott began to be a productive composer once again.

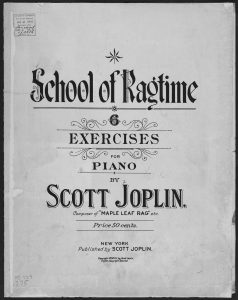

About that time, he started to write a ragtime instruction manual. He had long been concerned about the “new” style of ragtime piano playing that emphasized speed over correct execution. And the purpose of the manual was to encourage the style he preferred. He also re-emphasized his conviction that ragtime should be accorded respectability as a musical form and that his rags in particular be played and viewed in the manner he wished. The booklet was prefaced with the following “Remarks”:

“What is scurrilously called ragtime is an invention that is here to stay. That is now conceded by all classes of musicians. That all publications masquerading under the name of ragtime are not the genuine article will be better known when these exercises are studied. That real ragtime of the higher class is rather difficult to play is a painful truth which most pianists have discovered. Syncopations are no indication of light or trashy music, and to shy bricks at ‘hateful ragtime’ no longer passes for musical culture. To assist amateur players in giving the ‘Joplin Rags’ that weird and intoxicating effect intended by the composer is the object of this work.”

And so he composed a booklet containing six piano exercises in the “correct” way to play ragtime and called it The School of Ragtime. He issued it himself in 1908, and thus became the first Black ragtime composer to publish such a manual. (Back in 1897, it will be remembered, white ragtime pianist, Ben Harney had issued Rag Time Instructor). Joplin evidently hoped to reach a wide audience with his manual, for he priced it at only fifty cents per copy.

“Sensation—A Rag,” Joseph Lamb’s first published rag and the one to which Joplin had lent his name as arranger, was issued that year. With it Stark and Lamb would begin a profitable collaboration. Joplin would get no royalties from sales of the sheet music; his intent in lending his name to the piece had been solely to help the young and struggling composer.

Joplin published three rags of his own in 1908, “Fig Leaf Rag,” “Sugar Cane,” and “Pine Apple Rag.” “Fig Leaf Rag” was issued by Stark and, of the three compositions, is the one that harkens back most to his earlier style. However, it contains considerable experimentation, notably a heavily chorded trio and a distinctive choral quality in the final section. Its subtitle, “A High-Class Rag,” joins the introduction to The School of Ragtime in emphasizing Joplin’s concern with the respectability of his compositions.

Having established a good relationship with Seminary Music Company, Joplin published with them the two other rags issued that year. Both reflect his constant experimentation, particularly with choral and songlike qualities. Both are workmanlike in quality. Both sheet music issues contain the standard admonition about not playing the pieces fast as well as an added bit of instruction, a tempo marking = ♩ 100. Curiously, this is a faster tempo than many Joplinophile pianists prefer, and may indicate that at the time Joplin was being influenced toward faster tempos in spite of himself. He departed from his customary behavior in another manner at about that time. Generally described as a modest man and a good but not flashy dresser, Scott may have rather surprised ragtime musician Chauf Williams when he happened to bump into Joplin in New York in 1908. Williams remembers that Joplin was dressed up like a Fancy Dan, and sporting diamonds! (36)

Joplin was hard at work on his second opera, the first draft of which he had completed while still in St. Louis. (37) It was a story about a young Black woman on a Southwestern plantation who attains a position of leadership within the local Black community by virtue of her education. He may already have decided to call it Treemonisha. Joseph Lamb recalled that Joplin played some of the music for him in New York in 1908 and confided in him his dream of its production. (38)

Unlike the earlier A Guest of Honor, Scott did not call this a ragtime opera. It was a folk opera, and evidently he told a lot of other people besides Joseph Lamb about it. The March 5, 1908, issue of the New York Age carried in its theater section the following article:

COMPOSER OF RAGTIME NOW WRITING OPERA

Since syncopated music, better known as ragtime, has been in vogue, many Negro writers have gained considerable fame as composers of that style of music. From the white man’s standpoint of view he at present is inclined to believe that after writing ragtime the Negro does not figure.

There are many colored writers busily engaged even now in writing operas. Music circles have been stirred recently by the announcement that Scott Joplin, known as the apostle of ragtime, is composing scores for grand opera.

Scott Joplin is a St. Louis product who gained prominence a few years ago by writing “The Maple Leaf Rag,” which was the first ragtime instrumental piece to be generally accepted by the public. Last summer he came to New York from St. Louis and it was the opinion of all that his mission was one of placing several of his ragtime compositions on the market. The surprise of the musicians and the publishers can be imagined when Joplin announced that he was writing grand opera and expected to have his scores finished by summer.

From ragtime to grand opera is certainly a big jump—about as great a jump as from the American Theatre to the Manhattan and the Metropolitan Opera Houses. Yet we believe that the time is not far off when America will have several S. Coleridge Taylors who will prove that the black man can compose other than ragtime music.

The composer is just in his thirties and is very retiring in manner. Critics who have heard a part of his new opera are very optimistic as to its future success.

In his excitement about Treemonisha, Scott was able to forget his disappointment over his inability to get his first opera A Guest of Honor, produced. Indeed, it is likely that in the face of his hopes for Treemonisha he became dissatisfied with the earlier opera, saw it as a merely adequate first attempt at operatic form, and ceased to value it. This seems the only way to explain the fate he allowed to befall A Guest of Honor.

In the copyright files in the Library of Congress, on the card for A GUEST OF HONOR, there is a 1905 notation that no copies of the opera had ever been received. (39) Scott Joplin must have been aware of this, for he would have received a copyright notice had the piece reached the Copyright Office.

During his years of traveling before he settled permanently in New York, Scott was frequently short of funds and at times unable to pay his bills. It is said that one time when he could not pay his rent at a Baltimore boardinghouse, he left a trunk full of his possessions with the landlady, intending to reclaim his possessions when he was able to pay the money he owed. He never returned for the trunk. (40) A copy of A Guest of Honor may have been in it.