7 Chapter VII: Treemonisha

Scott Joplin and John Stark were having another one of their disagreements. Scott had excitedly talked about Treemonisha to Stark, only to be rejected almost out-of-hand. Since the commercial failure of the full-length version of The Ragtime Dance, Stark had no interest whatsoever in another lengthy, “high-class” work. Even if he had personally liked Treemonisha, he would have been forced to turn down its publication. He simply could not afford it.

Competition within the New York music publishing world was fierce. Between 1900 and 1914 there were nearly a hundred companies in the city publishing ragtime sheet music. And though the former piano and organ peddler was by no means a business novice, his ideas of competitiveness differed somewhat from the New York norm. His were based on hard work and straightforward dealings, not on “slickness.” Also to his disadvantage was his deep commitment to classic ragtime in an era when Tin Pan Alley dominated the field in popular music. Years later, his descendants would look back on the businessman Grandpa Stark with some bitterness and criticize him for not being more commercially minded. (1) However, even if he had been shrewder and sharper, and less committed to a particular quality of ragtime music, Stark would have had a hard time making it in New York as a small, independent music publisher.

The music publishing industry was beginning to consolidate, larger companies like Feist and Remick crushing competition from smaller concerns by either buying them out or forcing them out. A price war began, five-and-ten cent stores like F. W. Woolworth constituting the main offensive front. Larger concerns began to offer their sheet music at reduced prices and to send out pianists to plug their publications in the stores. Small, independent publishing companies could not compete on the same level. The best they could do was to send out protesting flyers to the retail dealers with whom they did business. This is what Stark had to say in one of his circulars:

Well, it’s like this. Some time ago the Whitney Warren Co. (Remick) impatient with the publishing business alone, conceived the idea of appropriating to himself the retail business of the country also. To this end he began buying up stands of the department stores.

Sol Bloom and others followed suit and soon there was a merry war on in retail prices. The “hits” have been persistently sold at gets . . . Leo Feist—nettled at seeing a competitor’s “hits” going faster than his own filled up the Woolworth 5 and 10ct. stores with music on sale . . . The New York Music Co (Albeit Von Tilzer) actually sends a man to these 10ct. stores to sing and push their pieces. It is said that Chas. K. Harris sold Knox 50,000 pieces at one order . . .

No one can tell what the end of this foolish greed will be. Were it not for the copyrights all music would be dragged to the level of cost for paper and printing.

Fortunately, as it is each publisher can only degrade his own publications. We will try to protect the dealer in a profit on our prints and hope we will not be dragged into junk-shop methods. It will be some time yet before our prints are found on sale in barber shops and livery stables.

Though many advertisements were equally verbose in those days, Stark’s advertisements were frequently and clearly aimed at a different trade from those of the larger music publishers. He might have done better if he had succumbed to a few gimmicks, but he was not that type of businessman, and in New York if you were not that type of businessman, you lost.

Leo Feist had started out as a small, independent dealer, too, back in 1899, when he had given up the corset business to go into music publishing. But Feist had come up with a gimmick. He created the Feist Band and Orchestra Club, which bands and orchestras could join for a dollar per year and in return receive twelve monthly issues of music, each piece a guaranteed new hit. He advertised heavily in The Metronome and before long his club was a huge success. “At the time we were jeered and laughed at, like most great inventors,” Feist recalled in 1923. “But the fact that practically every publishing house, especially the popular ones, has an orchestra club today proves that the idea was not ill conceived or carried out.” Feist also claimed to have created the “freak title,” with the publication of “Smoky Mokes,” by Abe Holzmann, another gimmick that attracted the public. John Stark refused to depart from the pretty titles he had traditionally used. Leo Feist prospered; John Stark struggled along. (2)

Added to his commercial difficulties were some grave personal hardships for Stark. His wife, Sarah Ann, was seriously ill, and the medical bills were mounting. Shortly, he would take her back to St. Louis, where she could be cared for by relatives. Stark was a stoic man, but his problems weighed heavily on him and affected his business and personal relationships. Joplin was a sensitive and understanding man, but his concern with his most monumental work overshadowed his awareness of his publisher’s difficulties. What eventually brought about a permanent break in the relationship, however, was a purely financial matter.

Early in 1909, beset by financial difficulties, Stark suggested to Joplin that in the future the composer’s works be purchased outright rather than on a royalty percentage basis. (3) Since all contracts between the two subsequent to that covering “Maple Leaf Rag” had been verbal ones, in a strictly business sense Stark was not actually remiss in suggesting such an arrangement, but he should have realized what Scott’s reaction would be. Naturally, Joplin preferred a royalty arrangement; outright purchases were for struggling new composers. Though he did not receive a substantial amount of money in royalty payments, there was always the possibility of a hit and a sizable profit. No, Scott preferred the old arrangement, and he stood firm in the face of Stark’s protestations.

Stark did not take lightly Joplin’s refusal of his suggestion. He felt Joplin owed him something for his long years of support for classical, Joplin-style ragtime. He considered the composer ungrateful. A stubborn man, unable to see the other person’s viewpoint when his ire was aroused, he vowed not to publish anymore of Joplin’s compositions. Angry himself at his publisher’s overbearing manner, Scott indicated that was fine with him.

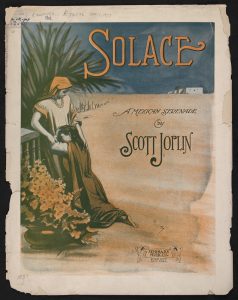

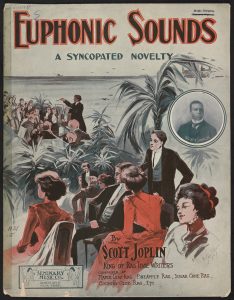

All of Joplin’s 1909 publications were issued by Seminary Music Company. It was a productive year for him. No less than six superb piano pieces were issued under his name that year, their very titles attesting to the happiness and peace he had found with Lottie: “Solace—A Mexican Serenade,” “Euphonic Sounds,” “Pleasant Moments.”

“Solace—A Mexican Serenade,” is Joplin’s only work in tango rhythm, a form not unknown in American music, having been introduced in 1860 with “Souvenir de la Havane” by Louis Moreau Gottschalk. Meant to be played in “very slow march time,” it is filled with warmth and with the unmistakable Joplin style, mellowed perhaps by his happy relationship with his second wife. Since the tango form probably originated in Argentina, the adjective “Mexican” likely indicates a searching for a new market. Having traveled across the Atlantic to achieve prominence in England and on the Continent, ragtime was now making inroads south of the U.S. border.

“Wall Street Rag” is a composition that has little to do in mood with its title. Once again its mood is optimistic. Descriptive headings for each of the movements’ areas are provided: Panic in Wall Street, Brokers feeling melancholy; Good time coming; Good times have come; Listening to the strains of genuine Negro ragtime, Brokers forget their cares. Yet the headings could have referred to any situation in which hope prevails. Tom Turpin continued to visit New York from time to time, and to see Joplin while he was in town. It is highly possible that Turpin, author of “Harlem Rag” and “Bowery Rag,” suggested the title of “Wall Street Rag” to him.

Another of Joplin’s 1909 publications, “Pleasant Moments,” was a further attempt to produce a ragtime waltz, although it is less experimental than his earlier “Eugenia.” This is a gentler waltz, fine to be sure, but not brilliant. The cover depicts a couple in the nostalgic boat on the water situation (in this case a canoe), the man paddling, the woman trailing one hand in the water and holding a parasol in the other. Altogether, a tender and gentle production.

The title of Joplin’s fourth 1909 rag, “Country Club Rag,” further suggests an urge to the “high class” and genteel. In musical form, it is a mixture of song and ballet and perhaps indicates Joplin’s concentration at the time on such forms in Treemonisha. Indeed, it has been suggested by one Joplinophile that, had the times and the circumstances been different, Scott Joplin might well have distinguished himself as a composer/choreographer. (4)

The 1909 publications are distinctive in their variety, and “Euphonic Sounds” is no exception. It may well be his most forward-looking piece, for it is a legitimate rag without the customary ragtime stride bass, and indeed, Joplin indicates this departure by subtitling the work “A Syncopated Novelty.” “Euphonic Sounds” was considered then and is considered now one of Joplin’s finest pieces. James Johnson, who recorded it in 1944, said, “Joplin was a great forerunner. He was fifty years ahead of his time. Even today, who understands ‘Euphonic Sounds’? It’s really modern.” (5) Years later Joshua Rifkin concurred.

The final 1909 rag, “Paragon Rag,” has a plantation sound, noteworthy in view of the plantation setting of Treemonisha. The second strain introduces the right-hand breaks or lead-ins that would later distinguish the player piano style of roll-recording players. This second theme also echoes a traditional New Orleans red-light district song, “Bucket’s Got a Hole in It—Can’t Get No Beer,” indicating that, though Joplin had traveled far away from his early days as an itinerant piano player, he had stored away for future use literally everything he had ever heard. His brain was an encyclopedia of folk melodies.

Altogether, the six 1909 compositions form the most stylistically successful group of Joplin pieces. These six alone would have assured him a place in musical annals, for they illustrate the versatility not only of Scott Joplin but also of the rag form. In these compositions, he showed that the rag could be adapted to everything from the waltz to the tango, and, perhaps most importantly in terms of the popular conception of ragtime, could dispense almost entirely with the traditional “oompah” bass and still be a rag.

Yet another rag in which Joplin was involved might have been published that year, a collaboration with Joseph Lamb, who recalled years later, “Scott wrote the first two strains and I wrote the last two and, so far as I recall our talking about it, if someone were told that either of us wrote the whole thing, no one would question it. If, as some people say, we both wrote pretty much alike it was certainly evident in that rag . . . I do not remember the name of the piece we wrote together and I don’t even remember how it went. I don’t know if he [Joplin] was able to have someone else publish it, but I don’t think he tried much because he was beginning to feel kind of low about his trouble with Stark. Stark liked it very much but he was as stubborn as Joplin about their differences and just wouldn’t take it.” (6)

The May 19, 1910, issue of the New York Age carried a Seminary Music Company advertisement for three of the Joplin rags it had published in the two previous years: “Pine Apple Rag,” “Euphonic Sounds,” and “Wall Street Rag.” Though these rags, and others Joplin had published in 1908–9, were among the finest of his career, they were not selling well, and Seminary Music Company would publish no subsequent Joplin compositions. Indeed, classic ragtime had been all but eclipsed by Tin Pan Alley, and even that highly commercialized form was beginning to decline in popularity. It had become little but cheap trash, and a reaction against it was inevitable. Most of the up and coming young Black composers in New York wanted nothing to do with ragtime and looked down on it as low-class Negro music much as many white composers did. They did not distinguish, and in their social insecurity did not care to distinguish, the beautiful and intricate compositions of Joplin, or James Scott or Joseph Lamb, from the hack music that came out of Tin Pan Alley. Men like Scott Joplin thus found themselves composing for an ever-diminishing audience. Their compositions were too difficult for the average parlor pianist and misunderstood by too many of those with the skill to play them.

There must have been times when Scott deeply despaired of the state of ragtime. He had devoted the better part of his life to achieving respectability for the form, and for himself as a purveyor of the form. He had seen ragtime struggle against the tide of public opinion and for a brief time to be carried along by that tide, only to see it thrown back, spit out, and forced to struggle against the tide once more. Had all his efforts been fruitless? There were two paths he could have taken. He could have abandoned ragtime, as most other ragtime professors were doing, and concentrated on more socially acceptable music, which he was certainly capable of writing. Or, he could have stubbornly kept on. He chose the latter course, defiantly refusing to admit he had committed himself to a form that would not make it. His defiance was particularly courageous, for not only did he continue writing classic ragtime, he reached higher. For Scott Joplin, a Black man deeply committed to American Negro folk rhythms, to focus his energies on writing the folk opera Treemonisha was like W. E. B. Du Bois mounting a serious campaign for the presidency of the United States.

He worked on Treemonisha like a man obsessed, despite the paucity of favorable conditions for composing. Unable to live off royalties from the sale of his music, Scott was forced to continue touring. It had been some five years since he had lived a settled life, and though Lottie was supportive and willing to travel with her husband, both she and Scott longed for the stability of a permanent address and a dependable income. They would not settle down for another year or so, and during the year 1910 they lived an essentially hand-to-mouth existence, supported to some extent by Lottie’s work as a domestic. (7) Scott published only two compositions in 1910, and one, “Pine Apple Rag-Song,” was merely a reissue of an earlier rag to which lyrics had been written by a Tin Pan Alley hack named Joe Snyder. Even as an instrumental, “Pine Apple Rag” had been very songlike, and it is likely that “Pine Apple Rag-Song” was primarily a potboiler intended to make some fast money.

The other composition, “Stoptime Rag,” is one of the happiest Joplin ever produced. He may well have written it during a period when work on Treemonisha was going well, perhaps after he had completed one of the gay numbers in the opera. It is the only post-“Eugenia” Joplin rag in which the by now traditional tempo admonition is missing. Instead, in a rather radical departure, Joplin gives the tempo direction as: “Fast or slow.” “Stoptime Rag” also includes this instruction: “To get the desired effect of ‘Stoptime’ the pianist should stamp the heel of one foot heavily upon the floor, wherever the word ‘Stamp’ appears in the music,” nearly the same instruction as is given in the “stamp” section in both versions of his earlier The Ragtime Dance. In “Stoptime Rag,” however, the “Stamp” instruction is used throughout, and the song rollicks from beginning to end, an exercise in folk dance that he would perfect in Treemonisha. Jos. W. Stem & Company, who published “Stoptime Rag,” also copyrighted the piece in Britain and in Mexico, where ragtime was enjoying considerable popularity.

By the end of 1910, Joplin had completed a second draft of Treemonisha and was hard at work trying to find a publisher for the book. It proved to be a frustrating task. “What headaches that caused him!” Lottie Joplin recalled years later. “After Scott had finished writing it, and was showing it around, hoping to get it published, someone stole the theme, and made it into a popular song. The number was quite a hit, too, but that didn’t do Scott any good.” (8)

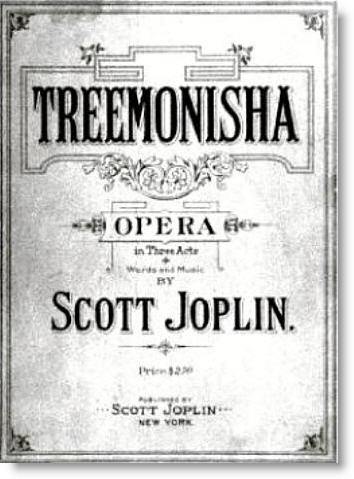

Somehow, Scott managed to get the money to publish Treemonisha under his own imprint, “Scott Joplin Music Pub. Co., New York City, N.Y.,” in May 1911. “Treemonisha—an opera in three acts,” was 230 pages in length and contained twenty-seven songs. Following is the story, as given in Joplin’s own words in the preface:

The Scene of the Opera is laid on a plantation somewhere in the State of Arkansas, North-east of the Town of Texarkana and three or four miles from the Red River. The plantation being surrounded by a dense forest.

There were several negro families living on the plantation and other families back in the woods.

In order that the reader may better comprehend the story, I will give a few details regarding the Negroes of this plantation from the year 1866 to the year 1884.

The year 1866 finds them in dense ignorance, with no-one to guide them, as the white folks had moved away shortly after the Negroes were set free and had left the plantation in charge of a trustworthy negro servant named Ned.

All of the Negroes, but Ned and his wife Monisha, were superstitious, and believed in conjuring. Monisha, being a woman, was at times impressed by what the more expert conjurers would say.

Ned and Monisha had no children, and they had often prayed that their cabin home might one day be brightened by a child that would be a companion for Monisha when Ned was away from home. They had dreams, too, of educating the child so that when it grew up it could teach the people around them to aspire to something better and higher than superstition and conjuring.

The prayers of Ned and Monisha were answered in a remarkable manner. One morning in the middle of September 1866, Monisha found a baby under a tree that grew in front of her cabin. It proved to be a light-brown-skinned girl about two days old. Monisha took the baby into the cabin, and Ned and she adopted it as their own.

They wanted the child, while growing up, to love them as it would have loved its real parents, so they decided to keep it in ignorance of the manner in which it came to them until old enough to understand. They realized, too, that if the neighbors knew the facts, they would some day tell the child, so, to deceive them, Ned hitched up his mules and, with Monisha and the child, drove over to a family of old friends who lived twenty miles away and whom they had not seen for three years. They told their friends that the child was just a week old.

Ned gave these people six bushels of com and forty pounds of meat to allow Monisha and the child to stay with them for eight weeks, which Ned thought would benefit the health of Monisha. The friends willingly consented to have her stay with them for that length of time.

Ned went back alone to the plantation and told his old neighbors that Monisha, while visiting some old friends, had become mother of a girl baby.

The neighbors were of course, greatly surprised, but were compelled to believe that Ned’s story was true.

At the end of eight weeks Ned took Monisha and the child home and received the congratulations of his neighbors and friends and was delighted to find that his scheme had worked so well.

Monisha, at first, gave her child her own name; but, when the child was three years old she was so fond of playing under the tree where she was found that Monisha gave her the name of Tree-Monisha.

When Treemonisha was seven years old Monisha arranged with a white family that she would do their washing and ironing and Ned would chop their wood if the lady of the house would give Treemonisha an education, the school-house being too far away for the child to attend. The lady consented and as a result Treemonisha was the only educated person in the neighborhood, the other children being still in ignorance on account of their inability to travel so far to school…

The opera begins in September 1884. Treemonisha, being eighteen years old, now starts on her career as a teacher and leader.

To summarize the rest of the story, by virtue of her education, Treemonisha represents a threat to Zodzetrick, the neighborhood conjurer, and his cohorts, Luddud and Simon. Unable to trick her through conjuration, they kidnap her and prepare to throw her into a wasps’ nest in the forest. She is saved just in time by her friend Remus, who disguises himself as the Devil and frightens the plotters, who run away.

The other people of the plantation are jubilant at Treemonisha’s safe return but vengeful toward Zodzetrick and his cohorts, who they feel should be punished. But Treemonisha advises forgiveness, and the people come to understand that they have been victims of their own ignorance. They ask her to be their leader, and when she suggests that the men might not want to follow a woman, she is assured that they will. The entire community then celebrates together.

It seems a rather simple and unsophisticated libretto, yet it deals with an important and profound subject—the birth and rise of a Black leader and the questions of self-determination and self-government. It can also be viewed as somewhat autobiographical. It is set near Texarkana and begins in 1884, when Joplin was still in the town. Though it is not known whether or not Scott ever had white teachers, his level of literacy indicates that his own mother stressed education as Treemonisha’s mother did. And his heroine can be said to reflect his own aspirations to do for the Negro’s music and for Black people through his music what Treemonisha did for her people in leading them out of ignorance and superstition. Not that he was egotistical about his mission. His opera is a historical one in the sense that Treemonisha triumphs over this ignorance and superstition back in the 1880s, more than twenty years before the opera’s publication. By placing the action at such a time, Joplin is saying, in effect, that Black people have already learned the lesson of Treemonisha and are free to determine responsibly their own futures.

Treemonisha was intended as a fantasy with enough reality about it to appeal to the essentially pragmatic American mind; and it is possible that Joplin was influenced by Lewis Carroll, whose Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland we know he read some years before 1911, for Carroll’s works can be read on either a purely fantastic or highly political level. Though he incorporated a number of fantasy elements, such as the huge wasps’ nest, the setting is the real world, the words are the Southern Black vernacular, and the music is pure American Black music.

Though the story may appear naïve to the modern mind, the music is not, and in Treemonisha, Joplin achieved what many consider his greatest musical accomplishment, for he synthesized in it all the ragtime forms which he had developed and experimented with throughout his career, while incorporating the ragtime form in a subtle and integrated manner. Musicologists distinguish in the tune “A Real Slow Drag” elements similar to those in Joplin’s 1904 composition “The Chrysanthemum” and his 1903 work “Something Doing,” in the prelude to Act III of Treemonisha, the dotted rhythm pattern in the C strain of the 1906 work “Eugenia,” and the upbeat interval of the fourth that is so prominent in “Maple Leaf Rag.” (9)

Of the twenty-seven tunes in the opera, two stand out as particularly remarkable—the beginning theme; “Aunt Dinah Has Blowed de Horn,” which captures the joy felt by the field workers when “quittin’ time” was signaled; and “A Real Slow Drag,” the haunting, dude walk melody that closes the opera. But there are many other memorable tunes: the strong and complex “The Bag of Luck,” the happy stoptime rhythm of “The Com-Huskers,” the ragtime waltz “Frolic of the Bears,” and the comic “We Will Rest Awhile,” in the best barbershop quartet tradition.

The music of Treemonisha is completely and distinctively American, and it is the first truly American opera, not imitative of the European form. Scott Joplin also choreographed the work. The dancing is as effective in emphasizing the mood as the music is. Here are his “Directions For the Slow Drag”:

- The Slow Drag must begin on the first beat of each measure.

- When moving forward, drag the left foot; when moving backward, drag the right foot.

- When moving sideways to right, drag left foot; when moving sideways to left, drag right foot.

- When prancing, your steps must come on each beat of the measure.

- When marching and when sliding, your steps must come on the first and third beat of each measure.

- Hop and skip on second beat of measure. Double the Schottische step to fit the slow music.

In published form, Treemonisha was available to anyone who was interested, and the fact that it was reviewed in only one publication should have indicated to Scott that there was not much interest in his opera. The one review, however, was laudatory, and it gave impetus to his stubborn optimism about the work. The review, which appeared in the June 24, 1911, issue of The American Musician, was a lengthy one. Following are excerpts:

. . . In literary productivity the colored man has not yet made himself very prominent. The works of Booker T. Washington and Lawrence Dunbar, however, are good examples of the products of the negro mind. In other departments of art the negro has heretofore practically achieved nothing, although his proclivity toward music is universally recognized. It is therefore an occasion for wonderment as well as for admiration when a work of undeniable merit has been wrought by one of this race.

Scott Joplin, well known as a writer of music, and especially of what a certain musician classified as “classic ragtime,” has just published an opera in three acts, entitled “Treemonisha,” upon which he has been working for the past fifteen years. This achievement is noteworthy for two reasons: First, it is composed by a negro, and second, the subject deals with an important phase of negro life . . . A remarkable point about this work is its evident desire to serve the negro race by exposing two of the great evils which have held this people in its grasp, as well as to point to higher and nobler ideals. Scott Joplin has proved himself a teacher as well as a scholar and an optimist with a mission which has been splendidly performed. Moreover, he has created an entirely new phase of musical art and has produced a thoroughly American opera, dealing with a typical American subject, yet free from all extraneous influence. He has discovered something new because he had confidence in himself and in his mission.

Scott Joplin has not been influenced by his musical studies or by foreign schools. He has created an original type of music in which he employs syncopation in a most artistic and original manner. It is in no sense rag-time, but of that peculiar quality of rhythm which Dvorak used so successfully in the “New World” symphony. The composer has constantly kept in mind his characters and their purpose, and has written music in keeping with his libretto. “Treemonisha” is not grand opera, nor is not light opera; it is what we might call character opera or racial opera. The music is particularly suitable to the individuals concerned, and the ensembles are noteworthy examples of artistic conceptions which conform to the character of the work . . . It is always a pleasure to meet with something new in music. In the many years that we have been associated with printed musical pages, this is the first instance we have observed some wholly strange notations. This composer has employed a very unique method of notating women crying and calls.

There has been much written and printed of late concerning American opera, and the American composers have seized the opportunity of acquainting the world with the fact that they have been able to produce works in this line. . . Now the . . . question is, are the American composers endeavoring to create a school of American opera, or are they simply employing their talents to fashion something suitable for the operatic stage and satisfactory to the operatic management? If so, American opera will always remain a thing in embryo. To date there is no record of even the slightest tendency toward the fashioning of the real American opera, and although this work just completed by one of the Ethiopian race will hardly be accepted as a typical American opera for obvious reasons, nevertheless none can deny that it serves as an opening wedge, since it is in every respect indigenous. It has sprung from our soil practically of its own accord. Its composer has focused his mind upon a single object, and with a nature wholly in sympathy with it has hewn an entirely new form of operatic art. Its production would prove an interesting and potent achievement, and it is to be hoped that sooner or later it will be thus honored.

Such words were “music” to Scott Joplin’s ears. What a fine review! How often he read and reread those words of praise from a (white) reviewer in a respected (white) publication, and though there were no more rave reviews, indeed no more reviews at all, Scott proceeded with his plans for Treemonisha, an action he probably would have taken had there been no reviews at all.

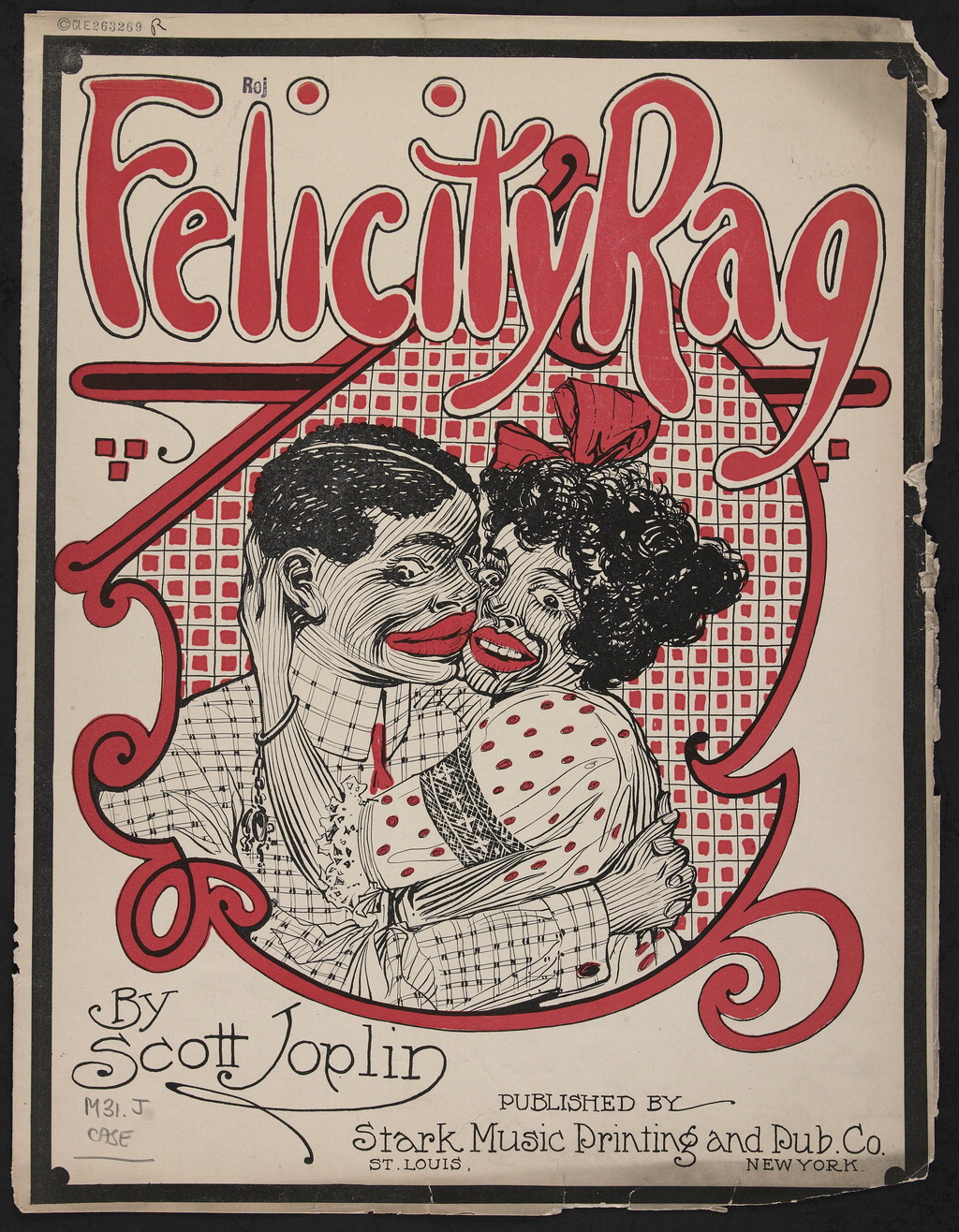

Joplin had no personal hand in the publishing of the other 1911 work that bears his name, “Felicity Rag,” another collaboration with Scott Hayden that John Stark published. In fact, given the state of Joplin’s relationship with Stark, it is probable that the rag is one Stark had purchased some years before. Considering Stark’s response to Joseph Lamb’s collaboration, it is unlikely that he would have purchased “Felicity Rag” subsequent to the break in 1909.

“Felicity Rag” was one of the last works to be published under the label Stark Music Printing and Pub. Co., St. Louis-New York, for shortly thereafter John Stark closed up his New York shop and went back to St. Louis. (10) Competition in New York was too much for an independent company like Stark’s, and with the death of his wife in 1910 he found the city an intolerably lonely place. Back in St. Louis, he went to live with his son E.J. and his family, and stubbornly continued to publish classic ragtime compositions from the printing plant “that ‘The Maple Leaf Rag’ had built.” (11) As late as 1916, the Stark company was running ads such as the following:

CLASSIC RAGS

DON’T LET THAT EVER FADE FROM YOUR MEMORY

As Pike’s Peak to a mole hill, so are our rag classics to the slush that fills the jobbers bulletins.

As the language of the college graduate in thought and expression to the gibberage of the alley Toot, so are the Stark rags to the Molly crawl-bottom stuff that is posing under rag names.

This old world rolled around on its axis many long, long years before people learned that it was not flat. Then they wanted to kill the man who discovered it.

St. Louis is the Galileo of classic rags. It is a pity that they did not originate in New York or Paree so that the understudy musicians and camp followers could tip toe and rave about them.

However they still have those Eastern games of wit and virtue “Somebody Else Is Gettin’ It Now”—”It Will Never Get Well If You Pick It,” etc., etc. Such as these they play over and over ad nauseum-and a bunch of French adjectives.

The brightest minds of all civilized countries, however, have seen the light and are now grading many of the Stark Rags with the finest musical creations of all time.

They cannot be interpreted at sight. They must be studied and practised slowly, and never played fast at any time.

They are stimulating, and when the player begins to get the notes freely the temptation to increase the tempo is almost irresistible. This must be kept in mind continuously. Slow march time or 100 quarter notes to the minute is about right.

When played properly the Stark Rags are the musical advance thought of this age and America’s only creation.