8 Chapter VIII: The Last Years

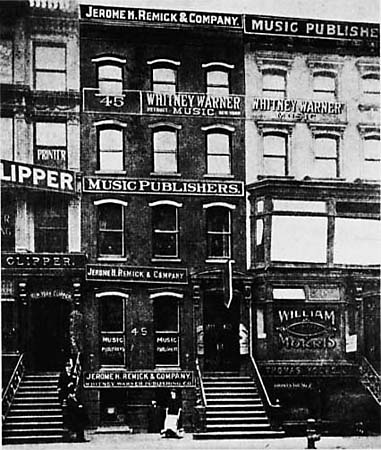

The Joplins finally settled down in late 1911 or early 1912, renting rooms in a boardinghouse at 252 West Forty-seventh Street between Broadway and Eighth Avenue in Manhattan. Scott was listed for the first time in the 1912 city directory as a composer. Forty-seventh and Broadway was the center of Tin Pan Alley in those days. Broadway was literally lined with rows of small music shops, long, narrow establishments each featuring at the front a pianist who played whatever tune a customer wanted to hear. All the latest songs and instruments were clipped onto overhead wires running the length of the store, and the customer walked along the rows of sheet music, reading the titles and making his selections. (1)

Though the area was near the Tenderloin and Hell’s Kitchen sections, both of which contained heavy concentrations of Blacks, it was not a predominantly Black neighborhood. Its many boarding establishments housed the show people, entertainers and musicians who made their living on Broadway and elsewhere in New York’s busy entertainment world, transient people who enjoyed a close camaraderie with one another. The Joplin rooms were frequently filled with people, for Lottie was jovial and outgoing and Scott, though rather shy and quiet, enjoyed having around him people who appreciated his kind of music. For their part, the visitors were attracted to both Scott and Lottie. There was always good food and good talk at the Joplins’, and Scott did his best to help out his friends whenever he could.

Unfortunately, none of his friends was in a position to give him the help he needed. They were not moneyed people, and they enjoyed no connections with people who were. Though they encouraged him in his efforts to produce Treemonisha, they could not help him to realize his dream. He was forced to pound the pavements himself and he did so, tirelessly, for months on end, armed no doubt with copies of the laudatory review that had appeared in The American Musician, but becoming increasingly frustrated by the lack of interest in his opera. When he worked, he worked on Treemonisha, and he published only a single composition in 1912, “Scott Joplin’s New Rag,” issued by Stern. A joyful, melodic piece, it may well have been written back in the spring or early summer of 1911, after the score of Treemonisha had been published and had received the one glowing review. Interestingly, the tempo instruction is not the usual “Do Not Play This Piece Fast,” but is instead “Allegro Moderato,” as if to indicate Joplin’s view of himself as primarily a composer of opera. The title, too, indicates an ego-involvement not previously seen. It is a fine rag, viewed by some musicologists as being in the “old vein.” Perhaps it was a piece that he had roughed out years before.

Certainly Scott was not doing much new composing, not even of potboilers for the sake of ready cash. Scott had apparently sworn off such commercialism; he would make it with Treemonisha or he would not make it at all. The small amounts of money he received in royalties and Lottie’s earnings working as a domestic maintained a roof over their heads and kept their other creditors at bay. Scott tried to do his part, listing himself in the 1913 city directory not as a composer but as a musician and taking whatever jobs he could find. He also reworked some of the tunes in Treemonisha, and in 1913 he published in sheet music form revised versions of two of the numbers, “A Real Slow Drag” and “Prelude to Act 3.” Since he published both pieces himself, he put an additional strain on his and Lottie’s already meager financial resources.

Money was probably the least of Joplin’s worries, however. He was far more disturbed at the decline of ragtime and the attacks on ragtime that were increasing in such publications as the New York Age. In April 1913 he wrote to the music editor of that publication a letter that may explain his refusal to do any more potboilers and that definitely states his high opinion of true ragtime:

I have often sat in theatres and listened to beautiful ragtime melodies set to almost vulgar words as a song, and I have wondered why some composers will continue to make the public hate ragtime melodies because the melodies are set to such bad words.

I have often heard people say after they had heard a ragtime song, “I like the music, but I don’t like the words.” And most people who say that they don’t like ragtime have reference to the words and not the music.

If someone were to put vulgar words to a strain of Beethoven’s beautiful symphonies, people would begin saying: “I don’t like Beethoven’s symphonies.” So it is with the unwholesome words and not the ragtime melodies that many people hate.

Ragtime rhythm is a syncopation original with the colored people, though many of them are ashamed of it. But the other races throughout the world today are learning to write and make use of ragtime melodies. It is the rage in England today. When composers put decent words to ragtime melodies there will be very little kicking from the public about ragtime.

Barely four months after his letter was published in the Age, Scott got his first break, or so it appeared. The following item appeared in the August 7, 1913, issue of the Age:

Scott Joplin, the well known composer of ragtime, has interested Benjamin Nibur, manager of the Lafayette Theatre [in Harlem], in the production of his ragtime opera, “Treemonisha.” The opera will be produced at the Lafayette in the fall.

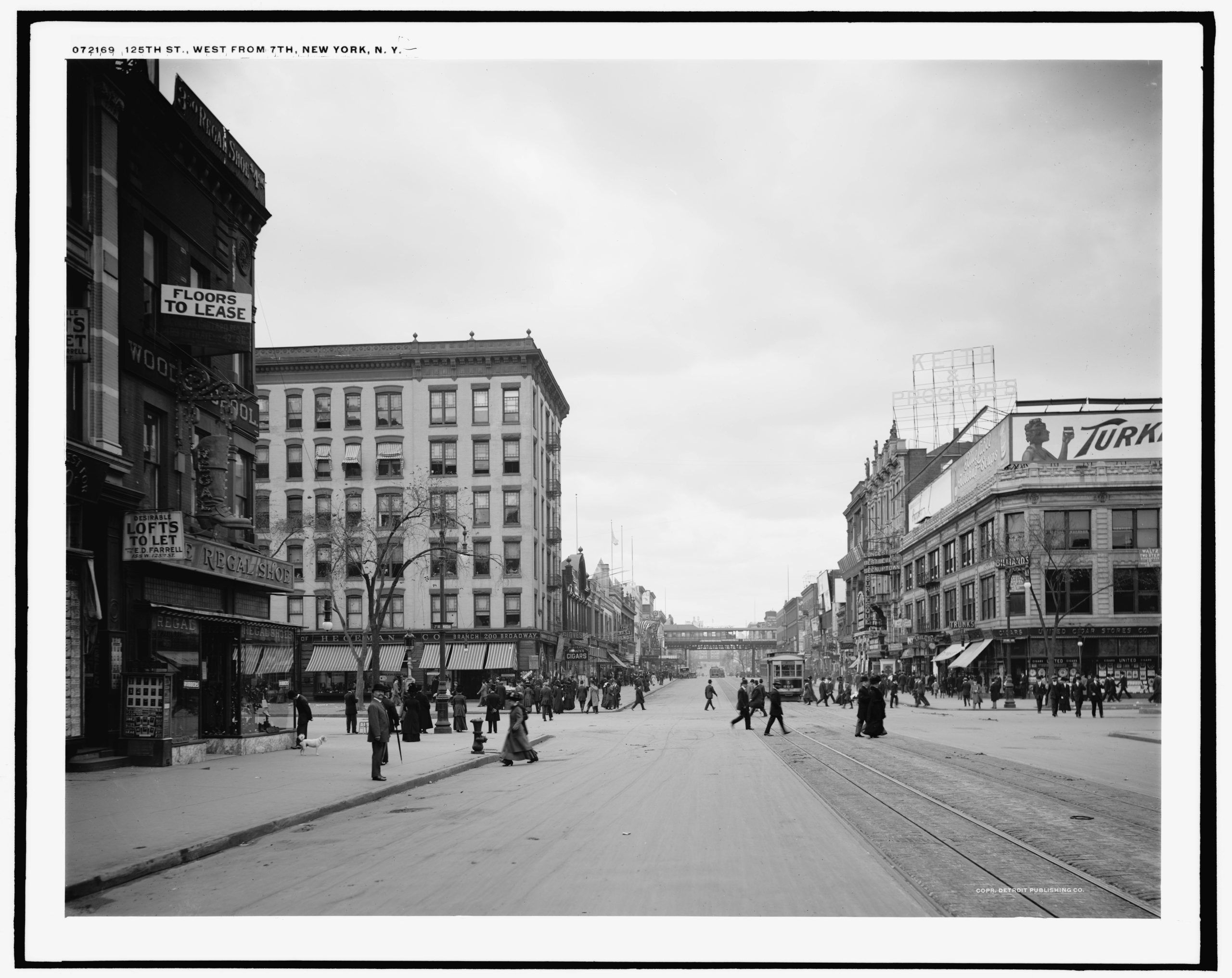

By 1913, the area known as Harlem was changing in complexion. The former poor rural community had developed rapidly after the 1870s, when it was annexed by New York City. Older and wealthier New Yorkers had moved to this “residential heaven,” whose undeveloped periphery housed poor Italian immigrants and a substantial scattering of Blacks (although they were far more disparate in Harlem than in the Tenderloin, for example). What set off the radical alteration of Harlem’s population was the construction of new subway routes into the neighborhood in the late 1890s. Speculators quickly bought up all the available Harlem land and property and erected apartment buildings to receive the waves of new people who would move to the area once it had become accessible to downtown Manhattan via the subways. Speculation reached fever pitch, and prices of land and property increased out of all proportion to their actual value. By 1904–5, the subway was nowhere near completion and the speculators realized they were saddled with too many empty buildings and astronomical mortgage payments to the banks. Landlords competed with one another to attract tenants, reducing rental rates or offering other “deals.” In desperation, some even began to rent to Negroes, charging them the traditionally higher rentals that Negroes usually paid.

It must have seemed to many of these new Harlemites that the millennium had come. After the squalor of their tenements in the Tenderloin and Hell’s Kitchen districts, they were suddenly offered brand new buildings, many of which had not even been occupied before. Harlem proper, with its wide, tree-lined avenues, was a genteel environment, and if its rents were high it was worth scrimping to live there. By 1914, some 50,000 Blacks would be living in Harlem, and many of its institutions would integrate.

The Lafayette Theatre, at 2227 Seventh Avenue, was built in 1912 to present white entertainment. The 2,000-seat theater originally had a segregated seating policy, but within a year it had changed to Negro entertainment and desegregated its seating. (2) Joplin’s Treemonisha was to be one of the first Black performances at the Lafayette.

It was August, and if the opera was to open in the fall, Joplin would have to work quickly. The August 14 issue of the Age carried the following notice:

Singers wanted at once—call or write Scott Joplin, 252 West 47th Street, New York City. State voice you sing.

But the opera never opened. Perhaps Joplin was unable to get enough performers and rehearse them in time. More likely, the change in plans resulted from a change in the theater’s management. The Coleman brothers, who took over that fall, preferred musical comedy offerings, and the show that opened in Treemonisha’s stead was a musical comedy production. After coming so close to seeing his dream of a production of Treemonisha realized, Scott was plunged into deep despair. For some weeks he was morose, inconsolable.

John Stark brought out Joplin’s final collaborative work that year, “Kismet Rag,” written with Scott Hayden. As in the case of “Felicity Rag,” though Hayden’s name appears on the first page, it does not appear on the cover, on which the name “Scott Joplin” alone appears. Also like “Felicity Rag,” it appears to be composed of material written some years earlier, but it is more effective. There is a vaudeville quality to it that is infectious. Evidently, Stark, with perhaps some prodding from Hayden, had relented and decided not to maintain his earlier policy of not publishing Joplin compositions. He may have learned of Joplin’s difficulties and obsession with Treemonisha, or he may simply have decided that publishing Joplin compositions was still good business.

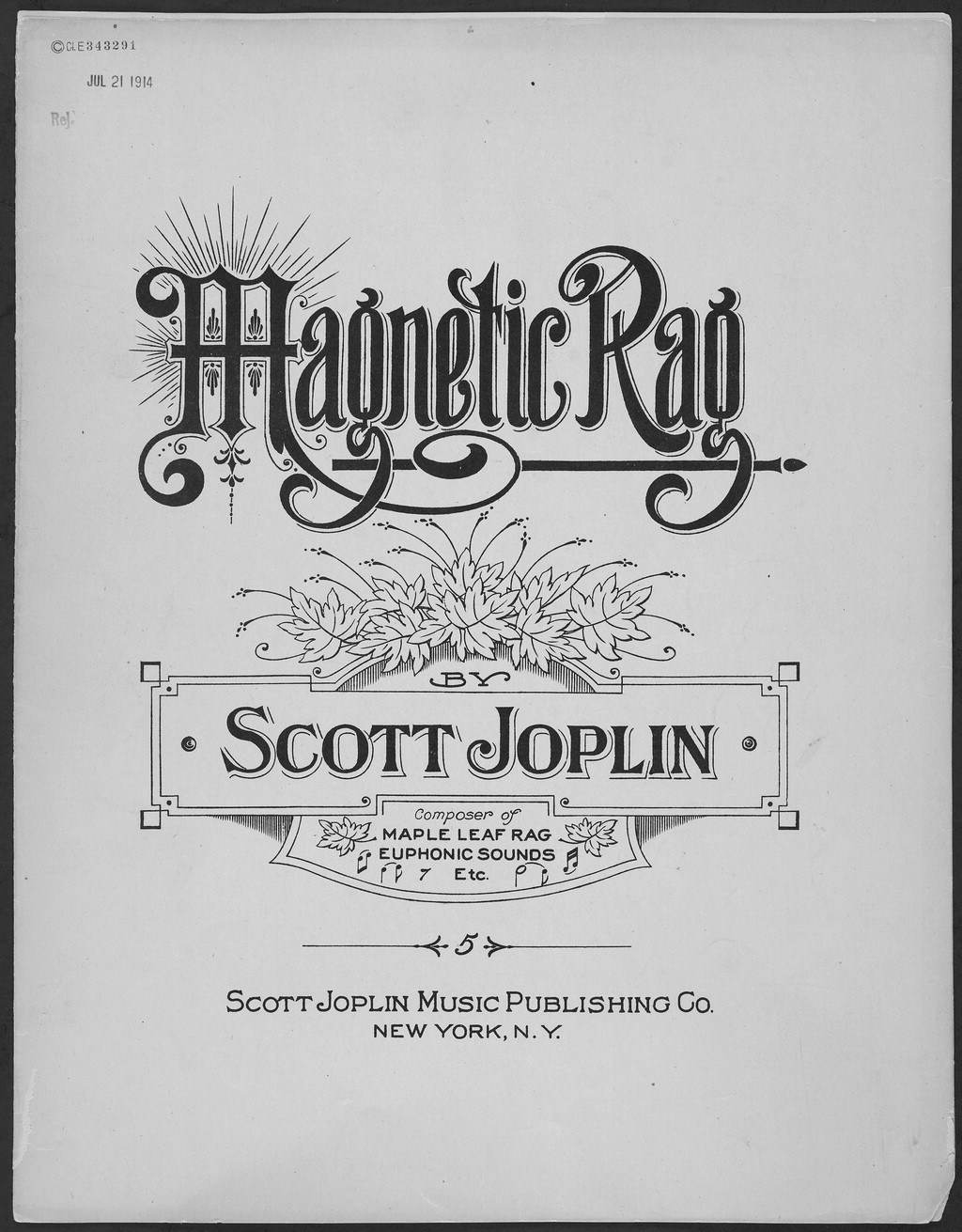

Scott managed to pull himself up out of his depression toward the end of 1913, and his creative spark returned with gusto. Early in 1914 he completed what many consider his finest rag, “Magnetic Rag,” which he published himself that same year. It has about it a gentle quality like “The Entertainer,” and its distinctive form and range of moods suggest to some musicologists a breakthrough to a Chopinesque form of ragtime, albeit a breakthrough that came too late. (3) He also renewed his efforts to revise various parts of Treemonisha, and early the next year he published at his own expense a revised version of “Frolic of the Bears.”

In 1915, the Joplins joined the general migration of New York Blacks northward to Harlem, renting rooms in a building at 133 West 138th Street. (4) Money was short, and the rent was substantial. To bring in more cash, Scott listed himself in the city directory as a music teacher. His declining fortunes in New York are clearly seen in the city directories. From “Scott Joplin, composer” in 1912–14, he becomes “Scott Joplin, musician” in 1915, and finally “Scott Joplin, music teacher” from 1916 until his death. Encouraged by his friends to keep revising his opera, Scott continued to work on Treemonisha and soon his former protégé Sam Patterson arrived in New York to help him. (5)

Since the death of Louis Chauvin in Chicago some years earlier, Patterson had traveled about and had eventually made his way to New York, still the music capital of the country. Meeting up with Joplin again, he urged his old mentor to press on with his work on Treemonisha. Joplin confided that he hoped to stage a performance of the opera in order to attract backers, and Patterson agreed to help him with the orchestration. They would work all day, Scott completing pages of the master score, and Sam copying out the various parts. At noon, Lottie would bring them lunch, and they would take a short break before resuming their work. Years later, Patterson recalled a typical lunch:

Joplin said, “Let’s knock off, I hear Lottie coming.” Just then the phone rang and I went to answer it. When I came back there were fried eggs on the table and Lottie was opening a bottle of champagne some folks she worked for had given her. I said, “These eggs are cold,” and Scott said, “Look, Sam, if they’re good hot, they’re good cold.” (6)

Scott’s and Lottie’s was a warm and gentle relationship. Though she worried about him, Lottie was always supportive of her husband, and she took great pains to provide a home atmosphere conducive to his work. In return, Scott treated her as the lady she most assuredly was. His last years were replete with disappointments, but they were also the years during which Scott enjoyed his most satisfying personal relationship.

Scott rented the Lincoln Theatre (7) on 135th Street in Harlem for a performance of Treemonisha sometime in the early part of 1915, hoping thereby to attract backers for a full-scale production. Quickly, he gathered together a group of young singers and dancers. As Sam Patterson recalled, he “worked like a dog” rehearsing the cast, who were likely working for little or no pay. There was no money for scenery, or costumes, or musicians, and Joplin hoped that the performance would succeed on the merits of its music, songs, and choreography alone. He was wrong. The performance was a flop. The small, mostly invited audience was polite but unenthusiastic. Sitting alone at the piano, playing all the orchestral parts himself, Scott Joplin despaired once again. That night he realized that further attempts on behalf of Treemonisha were futile.

Unfortunately, even if Treemonisha had been presented as a full production rather than as little more than a preliminary rehearsal, it would probably have not been a success. The Harlem audience, indeed the Black New York audience, was not ready for the subject matter of the opera. Many were familiar with opera, and with opera presented by Blacks. Black musicians were beginning to get jobs in the opera field. A Black singer named Theodore Drury had formed a Black troupe and beginning in 1903 presented such operas as Carmen, Faust, and Aida at the Lexington Opera House. (8) But Southern plantations and Black superstitions were too much a part of many Black New Yorkers’ recent past. Though they could view such subjects objectively, they were not ready to elevate their folk past to the level of art. Their tastes ran to other things, as stated in an article about the Lincoln Theatre that appeared in The Theatre magazine in 1916:

Having experimented with drama of many types, the director has discovered a marked preference for productions permitting the use of drawing rooms and pretty clothes. It is always a great point in a play’s favor if the actors, and more especially the actresses, are well dressed. The negro is essentially interested in ladies and gentlemen and has scant sympathy for crooks or Western bandits. (9)

Nor did the whites who witnessed the production, if indeed there were any whites in the audience, see any value in it. Undoubtedly, Scott had invited the critic who had written so glowingly about the published score of Treemonisha to attend the performance, but if the man did attend, he did not consider it worth writing about. Not one review, not one word about the performance appeared. Had it been panned, Scott would have had reason to continue fighting for his opera. But it was completely ignored. “American dillettanti,” wrote a critic in the London Times in 1913, “never did and never will look in the right corners for vital art. A really original artist struggling under their very noses has a small chance of being recognized by them . . . They associate art with Florentine frames, matinee hats and clever talk full of allusions to the dead.” (10) Scott could withstand anything, but he could not take silence.

He lapsed into depression once again, but this time he began to exhibit erratic behavior that worried Lottie. He developed strange tics of his facial muscles, began to stumble over difficult words; his handwriting deteriorated alarmingly, and he appeared physically weak. But when Lottie or Sam Patterson or one of his other friends suggested that he seemed tired, he insisted he’d never felt better, and then he would begin to talk excitedly about writing a musical comedy drama, or perhaps a symphony. He was exhibiting the symptoms of dementia paralytica, a disease that is a late manifestation of terminal syphilis. (11)

Having spent their small savings on the ill-fated production of Treemonisha, Scott and Lottie were nearly broke, and early in 1916 they moved once again, this time to 163 West 131st Street, where, at Lottie’s suggestion, they rented more rooms which she in turn rented out to transients. (12) Rumor has it that some of her boarders were extremely transient, using the place for their one-night stands. Though he appreciated the necessity of running such an enterprise, Scott could not work in that atmosphere. He rented a room two blocks away, at 160 West 133rd Street, where he worked and where he taught his students. But his productivity was minimal. He worked in spurts and, like his young protégé Louis Chauvin before him, seemed unable to complete anything, though he started numerous projects, among them orchestrations of “Stoptime Rag” and “Searchlight Rag” and two new piano pieces, “Pretty Pansy Rag” and “Recitative Rag.” (13) He became irritable, undependable. He neglected his students, and one by one they stopped coming.

His mind and his physical dexterity were deteriorating rapidly. He would sit down at the parlor piano and not be able to remember his own compositions. Sometimes, when he tried to compose, his mind went blank. For a number of years, his playing had been inconsistent. Eubie Blake heard him play “Maple Leaf Rag” in 1911 and thought he was terrible. Ragtime musician Dai Vernon had an entirely different impression in 1913. In that year, a friend took Vernon to a publisher’s office on Broadway. They found Scott in one of the composing/arranging rooms, playing “Maple Leaf Rag.” Vernon remembered that he played it “very, very well—but not too fast. It was in strict time with a positive beat, but it seemed to flow very beautifully. He didn’t appear to add any extra notes outside of what were on the music, except that he added an introduction and a fill at the end . . . a nice, quiet fellow, obviously engrossed in his music.” (14)

By 1916, however, his playing inconsistency had become even more marked. Pianolas and player pianos had become very popular, and because classic ragtime pieces were too difficult for the average person to play, classic ragtime piano rolls sold particularly well. In April 1916, Joplin recorded several rolls for the Connorized label, among them one of “Maple Leaf Rag” and one of “Magnetic Rag.” In June, he recorded “Maple Leaf Rag” again, this time for the Uni-record Melody label. The second version is disorganized, amateurish, a startling departure from the Joplin reputation even as a mediocre player. It is difficult to ascertain whether the difference in these rolls is due to differences in Joplin’s playing or to editing on the part of the people at the Connorized company. Though most of the Connorized rolls specifically state “played by Scott Joplin,” in the early days of piano rolls the manufacturing companies loved to orchestrate the rolls. The Connorized version of “Maple Leaf Rag” contains some notes that a human could not have played. (15)

Scott still had lucid periods, but they became fewer and were of increasingly shorter duration. During those periods, he worked frenetically at his music, aware, perhaps, that his time was running out. Defiantly, he pursued the extended forms that had played such a crucial role in his demise. In the fall of 1916 he sent the following notice to the New York Age, which ran it in the September 7 issue:

Scott Joplin, the composer, has just completed his music comedy drama “If,” and is now writing his Symphony No. 1. He has studied symphonic writing. (16)

Increasingly that fall and winter, however, Scott hadn’t the capacity for an emotion as strong as defiance. His emotions and senses were dulled. He felt neither pleasure nor sorrow and he was oblivious to physical pain. On good days, he was preoccupied with the safety of the unfinished manuscripts that littered his desk and piano, and one day in late December 1916 or early January 1917 he burned most of those scripts. Shortly thereafter he descended into the final stage of his disease. (17)

Scott was admitted to Manhattan State Hospital on February 5, 1917. (18) He was so mentally feeble that he could not even recognize the friends who came to visit him. Paralyzed, he lay motionless in his bed, dying slowly from weakness. In the March 29 issue of the New York Age there was this brief note:

Scott Joplin, composer of the Maple Leaf Rag and other syncopated melodies, is a patient at Ward’s Island for mental trouble.

Scott died at the age of forty-nine on the evening of April 1, (19) a fitting date, in the cynical view, for the death of a poor, Southern-born Black man who had aspired to write opera and to elevate a “low-class” music to the level of symphonic writing. The very month he died, Carl Van Vechten, who would later become such a champion of Black culture, wrote in Vanity Fair an article praising ragtime as a true American music. However, it was white composers like Louis Hirsch, Irving Berlin, and Lewis F. Muir, whom he singled out for praise. “. . . the best ragtime,” he stated, “has not been written by negroes.” (20)

“You might say he died of disappointments, his health broken mentally and physically,” Lottie Joplin later said of her husband. “But he was a great man, a great man! He wanted to be a real leader. He wanted to free his people from poverty and ignorance, and superstition, just like the heroine of his ragtime opera, ‘Treemonisha.’ That’s why he was so ambitious; that’s why he tackled major projects. In fact, that’s why he was so far ahead of his time…You know, he would often say that he’d never be appreciated until after he was dead.” (21)

A modest funeral was held at the G. O. Paris funeral home at 116 West 131st Street on the afternoon of April 5, 1917, (22) and Scott was buried in a common grave in St. Michael’s Cemetery on Long Island. Years before, Scott had made a request: “Play ‘Maple Leaf Rag’ at my funeral,” he had said to Lottie. But when the time came, Lottie decided it just was not appropriate to do so. Years later, she sadly confided, “How many, many times since then I’ve wished to my heart that I’d said yes.” (23)

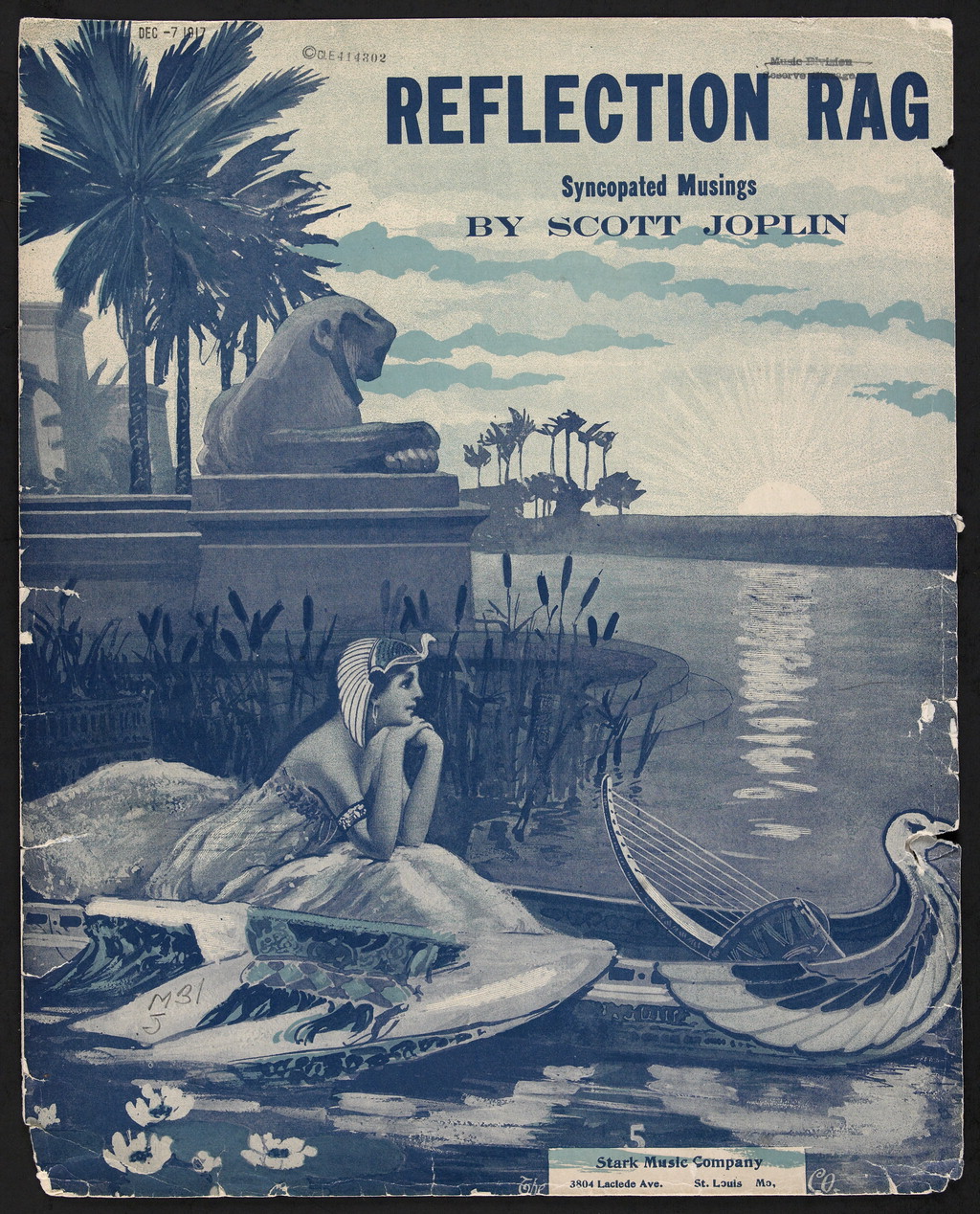

Eight months later, as a memorial tribute, John Stark issued the last Joplin rag, “Reflection Rag—Syncopated Musings.” Some musicologists feel it is one of his most classical and most beautiful. Others believe it was a piece that Stark had kept in his files for some time, and consider it so untypical of Joplin that its attribution is questionable. What is important is the intent of the publication, for despite their differences Joplin and Stark had enjoyed a high respect for each other. “Here is the genius,” wrote Stark, “whose spirit . . . was filtered through thousands of . . . vain imitations.” (24)