Prologue: The Rediscovery of Scott Joplin

In April 1917 the family back in Texarkana did not know that Scott Joplin had just died. They learned about it some months afterward, and gradually the news spread to the far-flung cities and towns where other members of the family were scattered. Fred Joplin, Scott’s nephew, had disregarded the wishes of his elders and gone on with his piano playing. In 1916, he had left home to pursue his career, but he had not sought out his uncle Scott, if indeed he knew where Scott was living; instead, he had traveled to join friends in Kansas City. At the time of Scott’s death he was in Montana, and it was not until some years later, on a return visit to Texarkana, that he learned of his uncle’s death. (1)

The Joplins were not a close family. Most of the Joplin men seemed to have traveling in their blood. Scott’s brother Robert continued to travel through the Midwest, working as a cook, and giving concerts whenever he could. “I lived in Chicago and he and his wife came to visit me in the early twenties,” Fred Joplin recalls. “He was a baritone, and he put on two or three concerts. Now Willie, I never did see him.’” (2)

Will, another brother of Scott’s, had spent some years in St. Louis with Scott and Robert. He had married there, but his wife had died (3) and he had returned to Texarkana for about a year in 1912, taking a room at 411 Hazel Street and listing himself in the city directory as a laborer. He left the town sometime in late 1912 and began to travel again.

Scott’s older brother, Monroe, had remained in Texarkana until sometime in early 1912. In 1910 he had listed himself in the city directory as a car cleaner, although he had usually worked as a cook. In 1912 he moved his family to Texarkana’s Iron Mountain addition, but shortly thereafter he got a job in Naples, Texas, and went to live there, leaving his family in Texarkana. Rosa, his second wife, became ill, and in 1913 she and her children went to live with a sister in Marshall. She died in 1915 and Monroe remarried. He died in Naples, Texas, in 1933. (4)

Between 1906 and 1913, Scott’s father, Jiles Joplin, lived with his granddaughter, Mattie, who had married Reverend Titus Harris and moved over to the Iron Mountain addition. When Rosa and her children went to Marshall, Monroe moved Jiles into their vacated house in the Iron Mountain addition, where the old man lived until he died on September 4, 1922. Monroe, who supplied information for the death certificate, said his father was “100 or more” when he died; actually, Jiles was about eighty. (5)

Eventually, Fred Joplin returned to Texas, where he and his sisters, Mattie Harris, Donita Fowler, and Ethel Brown, maintained the Joplin family ties to the area. (6) But neither they nor other members of Scott Joplin’s family, while they were still active, appear to have made much attempt to keep Scott’s name alive. Nor did most of Scott’s onetime protégés, Scott Hayden, Arthur Marshall, Sam Patterson, and Joseph Lamb among them. Not that any of these people had the influence necessary at that time to bring about a Scott Joplin music festival, or even a Scott Joplin memorial of some sort.

For a time, only Scott’s widow, Lottie Joplin, carried the torch. Left alone in New York City, this resourceful woman had continued her boardinghouse business and made it respectable. She remained at 163 West 131st Street, where she had lived with Scott until 1921 and thereafter operated similar establishments at 251 West 131st Street and 212 West 138th Street, (7) housing at various times such music greats as Jelly Roll Morton, Wilbur Sweatman, and Willie “The Lion” Smith. Knowing how important the opera Treemonisha had been to her husband, she worked hard to get it produced. “I tried to get it on Broadway for years,” she said in 1950, “and I remember that Earl Carroll once seemed really interested in the idea . . . But things never materialize when you want them to, and next I knew, Earl Carroll had gotten into difficulties over some girl and that bathtub of champagne, and he told me, ‘Lottie, I guess there’s no chance now.’” (8)

Around 1930, Samuel Brunson Campbell, a white pianist whom Scott had befriended during his Sedalia period, took up the cause, stimulated by a rather unusual incident. Years before in Sedalia, Scott had given Campbell a half dollar, dated 1897, and told him to keep it for good luck. Campbell later recalled:

“Well, I carried that half dollar as a good luck piece as Joplin suggested. Then in 1903 I met another pianist in a midwestern city and we became chums. One day we decided to go frog hunting down at the river nearby. We got into a friendly argument as to who was the best shot, so I took my silver half dollar and placed it in a crack on top of a fence post as a target. We measured off and my friend fired and missed. I shot and hit it dead center. The impact of the bullet really put it out of shape, so on our return to the city I went to a blacksmith shop and with a hammer reshaped it as best I could and then carried it as a pocket piece as before. But one day I somehow spent it.”

Many years later, Campbell married and moved to California, where he set up a business. On May 1, 1930, a customer paid for a purchase with a silver half dollar—the very same half dollar that Scott Joplin had given him and that Campbell had used as a target twenty-seven years before. Quite naturally, he considered it an omen. It recalled old memories, especially the look in Scott Joplin’s eyes as he had presented the coin to Campbell. As Campbell later recalled, “that half dollar seemed to say: ‘Why don’t you write about Scott Joplin and early ragtime. Write his biography and other articles and sell them to magazines and newspapers?’

“And then it seemed to say: ‘Don’t you think it would be nice to make a piano recording of his “Maple Leaf Rag” just as he taught you back there in Sedalia, and use the money from these sources to erect a memorial monument over his unmarked grave for what he did in the field of early American music?’ I did all that with the exception that I never erected the monument. Instead I sent the money to his widow to help her in an illness of long standing . . . His widow once wrote me, ‘Of all Scott’s old friends, you are the only one who has ever offered to do anything for him.’ It was the least the ‘Ragtime Kid’ could do for an old friend.” (9)

Campbell did indeed write about Joplin, initially in an article called “The Ragtime Kid (An Autobiography),” but it was never published in his lifetime. How hard he tried to get it published is not known, but it is unlikely that it would have inspired much interest. America was in the throes of the Jazz Age. Duke Ellington reigned with his Cotton Club Band. Ragtime seemed dull and mechanical by comparison, and Scott Joplin had been all but forgotten, except by those who had known him or by those few diehard ragtime enthusiasts who quietly set about collecting ragtime memorabilia. Among these enthusiasts was R. J. Carew, who had first heard “Maple Leaf Rag” played by a local music teacher in Gulfport, Mississippi, around 1906, when he was a teenager, and who had devoted much of the rest of his life to collecting Joplin rags. Having learned around 1916 that Joplin had written an opera, Treemonisha, he made every effort to secure a copy but was unable to do so.

The ragtime underground continued to operate; as if by telepathy, ragtime aficionados learned of each other and sought each other out. In the summer of 1944, a young ragtime enthusiast from Portland, Oregon, Donald E. Fowler, called on Carew to discuss ragtime in general and Joplin’s ragtime in particular. The meeting resulted in collaborative articles on Scott Joplin that The Record Changer published that year. S. Brunson Campbell saw the articles and contacted Carew. In May and June 1945, The Record Changer carried two articles by Campbell/Carew on Joplin’s days in Sedalia.

“We were happy to learn that these articles were a source of some pleasure to Joplin’s widow, Mrs. Lottie Joplin, who is still living in New York,” wrote Carew in 1946. “Not so long ago the postman left a flat rectangular package inside my screen door. A rather heavy package for its size, I thought, as I tore off the wrappings. With the excess paper out of the way I found myself with a prize in my hands. Yes, it was a copy of Scott Joplin’s opera, ‘Treemonisha,’ autographed by Mrs. Scott Joplin. My thirty-year search for the work had finally ended. S. Brun Campbell wrote me shortly afterward that he had suggested to Mrs. Joplin that she send me a copy of the opera. Needless to say, I am exceedingly grateful to Mrs. Joplin and Mr. Campbell for their kindness in this matter.” (10)

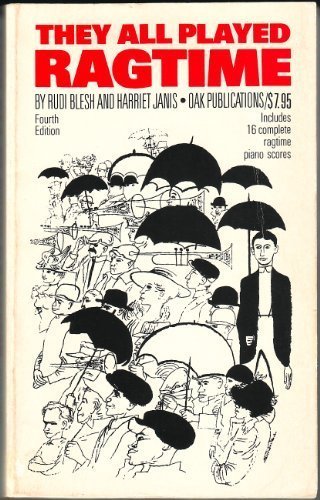

Ragtime in general and Scott Joplin’s music in particular were beginning to enjoy a renaissance, albeit a minor one, as evidenced by such articles, and about the time they began to appear, Rudi Blesh conceived a book about ragtime and its foremost exponents. With Harriet Janis, Blesh researched the lives of the ragtime greats, and the co-authors were in the enviable position of being able to interview such men as Joseph Lamb and Sam Patterson and Arthur Marshall, for though they were old they were still very much alive and filled with vivid memories of the ragtime era. The resulting book, They All Played Ragtime, first published in 1950, brought to the general public for the first time the stories of the early ragtime greats and proved to be the generative work in literature on Scott Joplin. Based to a considerable extent on interviews with Lottie Joplin, the information on Joplin has provided source material for nearly every subsequent work that includes mention of him. The book did not, however, spark a popular Joplin revival.

Interest remained chiefly within the ragtime underground, which began slowly to grow. Here and there across the country pianists began to rediscover ragtime, which led to an appreciation of Joplin’s music, which led to curiosity about his background. In April 1959, John Vanderlee, a ragtime pianist in Fort Worth, Texas, and his wife Ann, now deceased, visited Texarkana. Through interviews with the Joplin family and friends and research into city directories and old census records, they compiled the most accurate and detailed account of Joplin’s early life up to that time. Their findings were not published, however, until 1973-74, when the Rag Times carried their account in two installments.

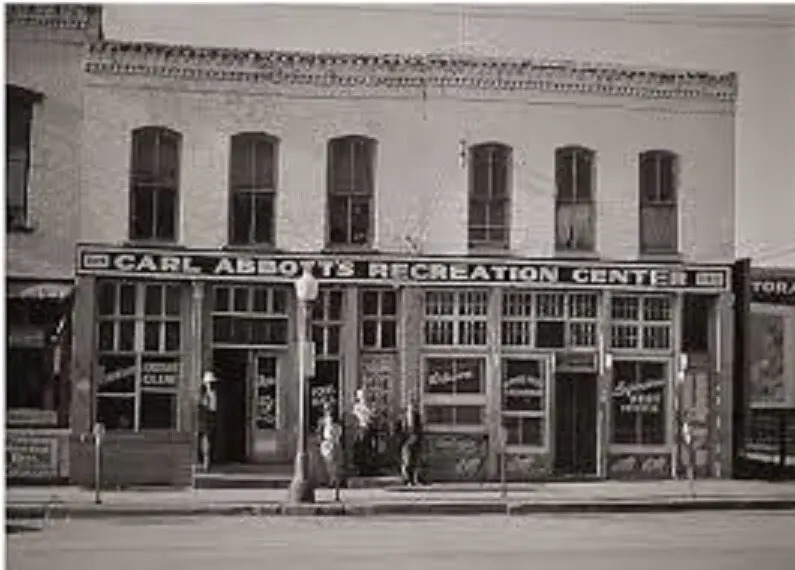

In 1953 in St. Louis, thirteen-year-old Trebor (Robert spelled backward) Jay Tichenor heard “Maple Leaf Rag” and immediately became a devotee of ragtime and Joplin. He grew up to become a ragtime “professor” himself and the pianist in the saloon of the Goldenrod Showboat, a registered landmark in St. Louis. By 1972 he had amassed countless rags in sheet music form and seven thousand piano rolls, between eight hundred and one thousand of them rags. His Joplin collection is one of the finest in the country and includes a swinging door (he suspects it was to one of the toilets) rescued from the old Rosebud Cafe, where Joplin had played before it was torn down. Proud of Missouri’s role in the birth of ragtime and proud that Joplin had spent some years in St. Louis, Tichenor has spent considerable time going through old telephone directories and culling bits of information on Joplin and other Black ragtimers in St. Louis from Black newspapers of the period.

As time went on the Tichenors and Vanderlees multiplied, and in the late 1960s the underground movement began to surface and coalesce. Dick Zimmerman, a ragtime pianist in California, founded Rag Times in May 1966, devoted to the resurgence of the form. Its motto was “Scott Joplin Lives!” and among the articles about ragtime greats, past and present, and current ragtime events, articles on Joplin appear frequently in its pages. The organization that functions as an umbrella for the periodical is called the Maple Leaf Club.

Also in the late 1960s a young musicologist and pianist named Joshua Rifkin, who had previously been interested in ragtime as a precursor of jazz, began to recognize classic ragtime as akin in many respects to classical music. At the time, he was acting as an informal adviser to Nonesuch, a recording company that specialized in Renaissance and Baroque music. He persuaded Nonesuch to issue a recording of Joplin’s works. “I felt the music should be treated seriously, that it should be put out on a classical label, with a dignified cover, and literate notes,” he says. (11)

Interestingly, some fifty years earlier a writer for the Detroit News had urged that ragtime be appreciated by the classicists. “If any musician does not feel in his heart the rhythmic complexities of ‘The Robert E. Lee,’ I should not trust him to feel in his heart the complexities of Brahms. I cannot understand how a trained musician can overlook its purely technical elements of interest. It has carried the complexities of the rhythmic subdivision of the measure to a point never before reached in the history of music.” (12) Unfortunately, both the writer of the article and Scott Joplin were too far ahead of their own time. Joplin had often said that his music would be appreciated only after he had been dead fifty years. He was off by only about three years in his prediction.

The first of three Rifkin recordings of Joplin’s work was issued in December 1970 and was an immediate success, not just by classical music recording standards but by music recording standards in general. In the next four years, Nonesuch would issue two more Rifkin recordings of Joplin. Like subsequent recorders of Joplin works, Rifkin played the rags slowly, as Joplin had insisted, giving listeners the opportunity to appreciate the beauties and the intricacies of the works. American musical tastes having changed once again, as is the cyclical tradition of history, American listeners were ready to appreciate them.

At least one segment of American listeners, that is. Reviewing the first Rifkin recording in the Sunday New York Times in January 1971, Harold C. Schonberg declared: “Scholars, get busy on Scott Joplin.” And among other musicologists, Addison Walker Reed did. His 1973 doctoral thesis at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, included the findings of the Vanderlees and material gathered by the Texarkana Historical Society and Museum. Scott Joplin and his music were still of interest primarily to ragtime enthusiasts and musicologists, however, as pianist and music collector Vera Brodsky Lawrence learned when she tried to find a publisher for a collected edition of Joplin’s piano pieces. Twenty-four publishing houses turned her down, feeling the book would not have a sufficiently wide market, before the New York Public Library agreed to do it. Both that first volume of piano pieces and her subsequent collection of Joplin’s works for voice have sold exceedingly well. This is not to suggest that the publishers who rejected the idea had poor market-forecasting procedures; they could not foresee that the name Scott Joplin would shortly become a household word and his music as familiar as that of Stevie Wonder.

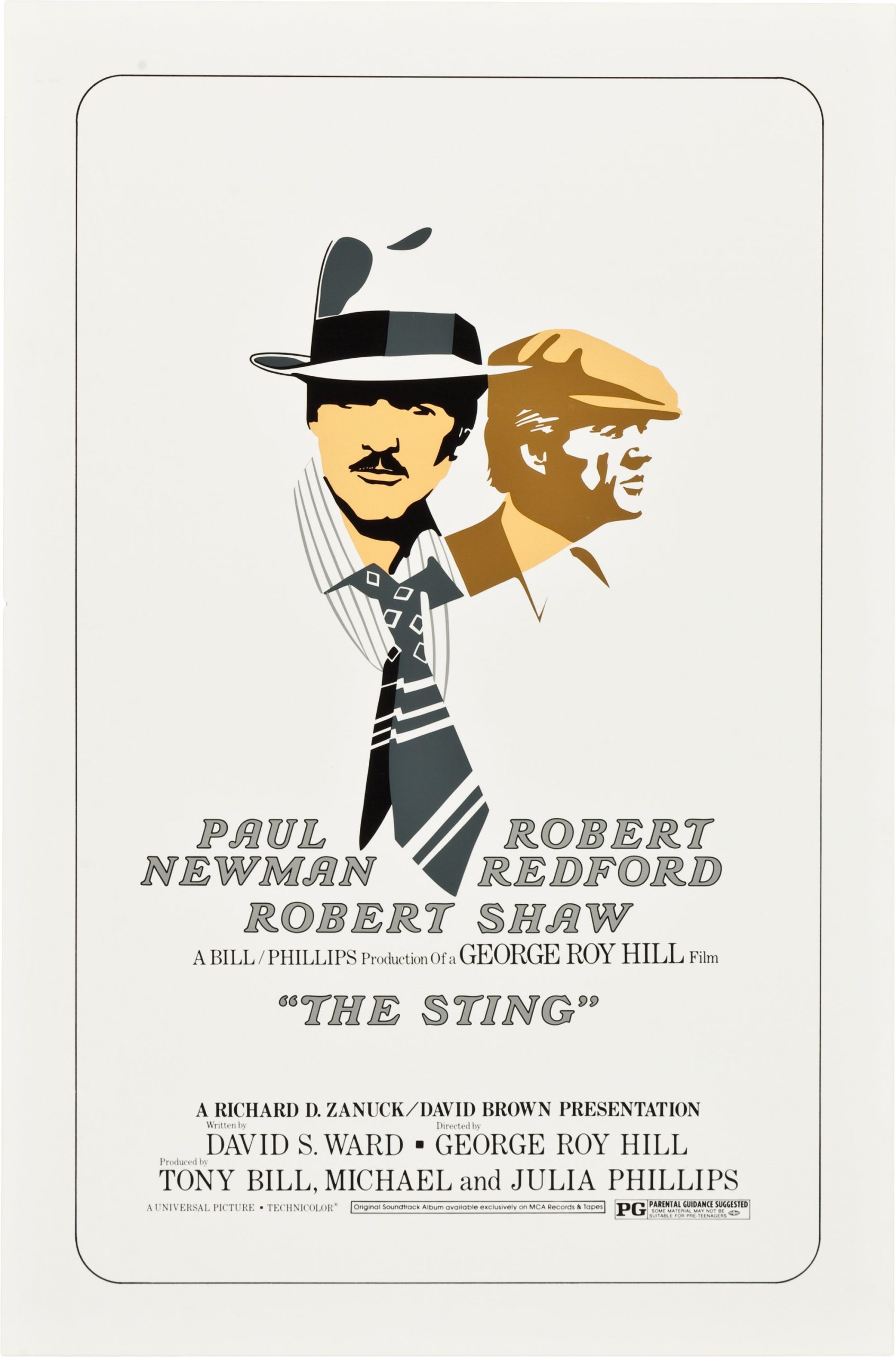

George Roy Hill, film director, heard a Rifkin recording of Joplin that his oldest son had purchased, and decided the music would make an excellent background for the movie on which he was then working, The Sting. Though he was aware that the era of classic ragtime and Joplin’s music had preceded the period of the film, which is set in the 1920s, he felt the humor and high spirits of Joplin’s rags captured the feeling he wanted. Hill brought in composer Marvin Hamlisch and together they selected the music for the score, which includes “The Entertainer,” “Gladiolus Rag,” “Pine Apple Rag,” “The Ragtime Dance,” and “Solace.” “The Entertainer” was renamed “The Sting” and served as the title song. Released in 1973, the film The Sting, won the Academy Award for Best Picture of the Year in 1974, and the score and title song also won Oscars. By the fall of 1974 the soundtrack of The Sting had sold over two million in records and tapes. (18) Suddenly, Joplin’s music and Joplin’s name were everywhere. By an extremely circuitous route, Scott Joplin had again reached the popular market.

Now, Joplin’s rags are available in recordings on a variety of labels by numerous pianists and ensembles. “Maple Leaf Rag,” in these recordings, has sold over a million copies. Ragtime pianists proliferate and major ragtime festivals are held each year in cities and towns across the country. The pages of ragtime periodicals are replete with announcements and reports of such gatherings. Rags by many composers are featured, but Scott Joplin seems to hover over these proceedings, never far from rag devotees’ minds, his name frequently on their lips.

The towns and cities where Joplin lived at different times in his life have taken steps to acquaint the world with their role in his career and in his music. In Missouri, particularly in Sedalia and St. Louis, the role of the region in the birth of ragtime was being rediscovered by the mid- to late 1950s. Many Sedalians had not even heard of Scott Joplin until the local newspaper carried an article about him, but once they had learned of him and his connections with Sedalia, they were quick to start a Scott Joplin Memorial Foundation. In 1961 a marble memorial plaque was installed on the corner of Main Street and Lamine Avenue, where the original Maple Leaf Club stood and where a parking lot now operates. It paid tribute not only to Joplin but also to John Stark, his first and most supportive publisher, Arthur Marshall, and Scott Hayden. At first there was talk of exhuming Joplin’s body from his grave in New York and bringing it to Sedalia to rest beneath the memorial, but the idea was given up when it was discovered that he was buried in a common grave with two other individuals and it would be difficult to ascertain which one was Scott. (14) In July of 1974, the first Scott Joplin Ragtime Festival was held in Sedalia. The sponsors had hoped to persuade the U. S. Postal Service to issue a Scott Joplin commemorative stamp, but the suggestion was rejected without explanation.

In St. Louis, the building at 2658-60 Delmar Boulevard (formerly Morgan Town Road), Joplin’s first residence in the city, was placed on the National Register of Historic Places by the U. S. Department of the Interior in 1977.

About the same time Missourians were beginning to rediscover Joplin, Texarkanans began to learn about their famous former citizen. In 1956, a group of jazz musicians presented a concert to benefit a local church. The master of ceremonies, George Beasley, mentioned Joplin in his introductory remarks and sparked the interest of one of the musicians, Jerry Atkins, a Texarkana businessman. Over the next twenty years, Atkins researched Joplin’s Texarkana period, though he found relatively few sources. Through the work of D.A.R. genealogist Mrs. Arthur Jennings and others interested in Texarkana history, a respectable amount of information has been compiled, and in 1971 the Texarkana Historical Society and Museum began to collect in earnest information on Joplin and memorabilia for a special, permanent Joplin exhibit.

In 1973, when the twin cities of Texarkana, Arkansas, and Texarkana, Texas, celebrated their centennial, their most famous citizen was honored with a Scott Joplin Centennial Concert, at which eighty-two-year-old John Vanderlee, who fourteen years earlier had come to town with his wife to gather information on the early life of Scott Joplin, played a selection of the master’s rags, and at which Joplin’s surviving relatives were honored guests. On November 24, 1975, a bust of Joplin commissioned by the twin city Bicentennial Commission was unveiled at the museum; in December 1975 the Texas side opened the Scott Joplin Park; in March 1976 the Arkansas Historic Preservation Program nominated Orr School for the National Register of Historic Places; in April the Texarkana Museum received a Scott Joplin plaque from the National Federation of Music Clubs; and in 1977 the Texas Historical Commission placed an historical marker on the Texarkana library grounds.

Joplin spent only a brief period of time in Chicago and was listed in the city directory for just one year, but Chicago, too, has paid its tribute. In the late winter of 1975, an elementary school was rededicated as the Scott Joplin Elementary School and the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers unveiled at the ceremony a bronze plaque honoring Joplin. (15)

Brunson Campbell would have been pleased with all these tributes and memorials. However, he died in 1952 and so did not live to witness them.

The paucity of information on Joplin’s life has moved music collectors and Joplinophiles to search for more, and a number of recent discoveries have helped to fill in the many and sizable gaps in his story. Additions have also been made to the list of Joplin memorabilia. Though Joplin’s opera A Guest of Honor has yet to be found, (16) one important discovery was made in 1970 by “Piano Roll” Albert Grimaldi. In preparation for a move, Grimaldi was sorting through a group of old piano rolls he had stored in his Los Angeles garage, when he came upon “Silver Swan Rag—Scott Joplin.” He had purchased the roll for a quarter from a thrift shop in Los Angeles some fifteen years earlier, when he knew nothing about either Joplin or ragtime. The original titled leader was missing, but Albert had copied the title and composer from the leader onto the roll when he had purchased it. Because the leader was missing and the brand of the roll was unknown, some questioned that the rag was indeed Joplin’s. However, subsequently a nickelodeon roll of the rag surfaced in the collection of Don McDonald of Balwin, Missouri, and the rag was found listed in a roll catalogue, credited to Joplin and dated 1914. The roll was transcribed and copyrighted in the name of the Joplin estate, and it was included in Scott Joplin: Collected Piano Works. (17)

In 1976 James Fuld of New York found a previously unknown song that Joplin had arranged. “Good-bye Old Gal Good-bye,” by H. Can-all Taylor, was published in 1906 by the Foster-Calhoun Company, Evansville, Indiana. Though the sheet music states the song was copyrighted, it was not. (18)

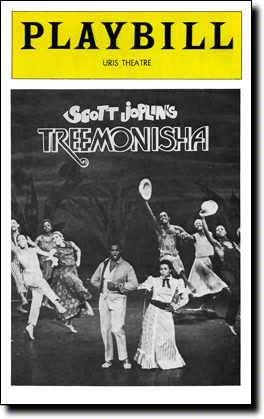

It was inevitable that someone would decide to stage a production of Joplin’s opera Treemonisha, and in 1972 its world premiere took place at the Atlanta Memorial Arts Center in connection with an Afro-American music workshop sponsored by Morehouse College. Later in the same year, a second production was presented at Wolf Trap Farm outside Washington, D.C. Both of these early productions were relatively straightforward renderings based closely not only on Joplin’s orchestrations but also on his choreography and staging instructions. Had Scott been alive, both would have “done him proud.” But others saw greater potential in Treemonisha, the potential for a truly grand production. In May 1975, such a production opened at the Houston Grand Opera. Directed by Frank Corsaro, choreographed by Louis Johnson, and orchestrated by Gunther Schuller, who has recorded several volumes of Joplin rags, this production of Treemonisha realized all of the opera’s possibilities, and it received excellent reviews.

Finally in September 1975, Scott Joplin’s dream was realized. Treemonisha opened at the Uris Theater on Broadway and played a limited engagement before packed houses, and though it departed in some ways from Joplin’s original concept, it remained true to his basic intent. To overcome the inadequacies of the story, Corsaro concentrated on much movement and high-spirited dancing and emphasized the whimsy and fantasy in the libretto. Franco Colavecchia’s costumes and stage sets helped the audience to follow the story, which was at times a difficult task, for Joplin included no spoken dialogue whatsoever. The producers could have added dialogue and more material to the plot, but they chose to remain true to the Joplin libretto.

Gunther Schuller was equally loyal to Joplin in the orchestration. “If you want to criticize Treemonisha from a cold, academic point of view, you can find plenty of weaknesses,” he has said. “For one thing, Joplin had never heard a lot of the music of his day—Stravinsky or Mahler, say—and he used the musical language of the eighteen-forties. But . . . it has a period charm that’s indestructible. When I orchestrated it, I resisted the temptation to ‘do something’ with it. I wrote as closely as possible to what Joplin would have done in terms of the instrumentation and abilities of pit bands of his day. I tried to keep in mind what Joplin would have had in his ear. If I had jazzed it up, it would have killed the period feeling . . . [Treemonisha] is a very uneven piece and certainly not a great piece of drama but, on the other side of it, it has some of the most beautiful music Joplin ever wrote.” (19)

The theater was small, intimate. The audience had about them an air of expectation, for they realized they were about to witness not just an opera but a bona fide historic event, and as the lights dimmed they leaned forward to register in their memories every moment. At times early in the performance there was an uncomfortable murmur, as they strained to understand the words that were sung and that alone told the story. But as the opera progressed they picked up the unspoken cues that communicated the action—in the expressions in the singers’ voices, the fantastical costumes and props, the tremendously expressive dancing. They were no longer constrained to enjoy the show because they wanted so much to see Scott Joplin succeed; they were able to relax and relish it without a sense of obligation. When the curtain came down, they did not want to leave, and when the dancers launched into a second and final rendition of “Aunt Dinah Has Blowed de Horn,” the theater fairly rocked with joy. The master would indeed have been pleased. Sadly, Lottie Joplin, who had tried so hard to get Treemonisha on Broadway, did not live long enough to witness the triumph. She had died, at the age of seventy nine, on March 14, 1953. (20)

The production of Treemonisha provided the impetus for the awarding to Scott Joplin posthumously of a Pulitzer Prize in 1976. It is probable that the prize was actually awarded to Joplin for the sum of his work and that Treemonisha was simply the obvious “hook” on which to hang it. Some critics did not wholeheartedly applaud the award. Gary Giddins, writing in the May 24, 1976, Village Voice, stated: “One hesitates to throw a wrench at such a pleasantly ironic, self-congratulatory, but deserving award, except that poor Scott, who died in 1917, is being used as a lever against more considerable black achievement. He has been found worthy because he has been discovered by the conservatory, because his music does not require improvisation, and because he wrote an opera to prove his seriousness.”

Many Joplinophiles were not overgratified by the award; for them, the real gratification has been the rediscovery of Joplin by the general public; the enjoyment his music has brought to millions, and their part in helping to make it all happen. But there is a certain pleasure in the knowledge that such vaunted recognition has been given to the man whose common grave remained unmarked for fifty-seven years.

In October 1974 that “oversight” was ameliorated. ASCAP (American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers) held a brief service at the site of the fifth grave in the second row of St. Michael’s Cemetery in Astoria, Queens. There, on the stubbly patch of ground between two other graves marked by stones, the bronze marker was placed. It read simply “Scott Joplin, American Composer,” and gave his birth and death dates. During Joplin’s lifetime, most of his fellow composers did not recognize his importance; now, at last, they paid him the honor due him. As the dignitaries stood viewing the marker, a soft breeze came up, wafting across the gravesite brightly colored maple leaves from the large tree nearby.