6 University of Florida and Black Community Engagement by Barbara McDade Gordon, Gwenuel W. Mingo, and Sherry Sherrod DuPree

Abstract: A review of the literature in Community Engagement provides the conceptual framework for documenting the University of Florida’s engagement with the Black communities in Gainesville. Community Engagement may be defined as a dynamic relational process that facilitates communication, interaction, involvement, and exchange between an organization and a community for a range of social and organizational outcomes. As a concept, Engagement features attitudes of connection and interacting participation. It is in this context that selected major engagements between the University and the local Black communities are examined. It focuses on three relational Community Engagement Models: Faculty Research & Service, Educational Outreach, and Religious Connections. The Chapter concludes with outcome-based strategies for future stronger Community Engagement Networks.

Section 1: Faculty Research and Service – Missions of a Public University by Barbara McDade Gordon

According to its mission statement, the University of Florida is a comprehensive learning institution dedicated to excellence in education and research to shape a better future for Florida, the nation, and the world. The three interlocking elements—teaching, research, and service—represent the University’s commitment to serve the state of Florida, the United States, and the global community. Central to the mission is the commitment to share the benefits of UF research and knowledge for the public good.

This chapter highlights research and service activities by UF faculty members that involve the African American/Black communities in the Gainesville area. The selections are organized by UF colleges and departments. Selections were made from perusing the faculty websites that showcased their research interests and activities; contacting Department Chairs and colleagues; discovering relevant presentations; and browsing the UF website, faculty publications, and reports of community activities. Research by faculty members is ongoing and continuous. Therefore, information in this publication may be updated, as necessary.

College of Agriculture and Life Sciences

Sally K. Williams, Ph.D. Associate Professor, Department of Animal Sciences.

Dr. Williams’ primary subject area is on poultry research in Florida, and she has also done work in Africa. She is one of a few African American faculty members in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences and has been awarded for her mentorship service in the UF Multicultural Mentoring Program for students of color. Through her sorority, Delta Sigma Theta, she has worked with girls and young women in Gainesville area, particularly encouraging them to consider and prepare for careers in the STEM fields. Dr. Williams often serves as a judge at science and engineering fairs hosted by Alachua County Public Schools. She also mentors students in these schools.

College of the Arts

Dionne Nicole Champion, Ph.D. Research Assistant Professor, Center for Arts in Medicine

Dr. Champion’s work focuses on the design and ethnographic study of learning environments that blend STEM and creative embodied educational activities, particularly for children who have experienced feelings of marginalization in STEM settings (for example, African Americans and girls).

She works with youth, K-12, and college students. Dr. Champion is currently developing a research program that studies ways to engage children in authentic STEM experiences and works with African American children at the UF Virtual Creative Arts Academy (VCAA). The VCAA successfully launched a pilot program with Gainesville’s Howard Bishop Middle School’s summer enhancement program (HBVCAA) and has received funding to help implement a one-year, in-school version of the program. She said that Howard Bishop administration actually reached out to VCAA to help design a program that would help students adjust and become more productive in the virtual classrooms which the Alachua County School District adopted as safety precautions due to the coronavirus pandemic. There are 17 total schools in Florida’s community partnership network who are becoming aware of the project. The program was a brainchild of the College of the Arts (COA) Center for the Arts, Migration, and Entrepreneurship (CAME), led by Director Osubi Craig. Her program with the COA/CAME/School of Music has procured the old fire station on Main Street as a location for community activities. They will work with people in the community to enable them to conduct their own research and evaluation to develop solutions to issues in the community. For more information you may visit the VCAA online: www.UFVCAA.com.

Welson Alves Tremura, Ph.D. Professor, School of Music and Center for Latin American Studies

Dr. Tremura organized a program of concerts held at the Bo Diddley Plaza in downtown Gainesville and other open spaces in the city, such as parks, to provide the community with the opportunity to intersect with the Arts at the University of Florida and to facilitate new possibilities for collaboration. He and another UF faculty member, Dr. Larry Crook, coordinated these concerts with the City of Gainesville Cultural Affairs Department. Students and local artists were invited to assist in the production and to perform at the concerts. As an ethnomusicologist, he explores the possibilities of acculturation among Latin American, African, and World Music an essential step towards building good communities. The following links are to concerts at the Bo Diddley Plaza in downtown Gainesville.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5cn6fhh6JkA. World Music Fest. October 14, 2011.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nbOkdiwHsas. World Music Concert. December 22, 2013.

Joan Frosch, Ph.D. Professor, School of Theatre and Dance; Director of the Center for World Arts

Dr. Frosch founded the Center for World Arts (CWA) with Dr. Larry Crook, an ethno-musicologist in the School of Music. She describes it as a living laboratory exploring the interface of arts and society. Her primary research and teaching are in African contemporary dance. The CWA links local artists from the Gainesville communities (African American and others) with global communities to expand the international reach and artistic breadth of UF’s academic programs. Recognizing the diverse and interconnected nature of the contemporary world, the Center tests new paradigms of research, curriculum, cultural programming, and public outreach. The CWA seeks to integrate a socio-artistic aesthetic into practice and study of the arts, exploring issues of identity, migration, race, gender, and privilege through the lens of the arts. More information on the CWA: https://arts.ufl.edu/centers/center-for-world-arts/about.

The Harn Museum

Eric Jefferson Segal, Ph.D. Director of Education and Curator of Academic Programs

Dr. Segal (see Figures 6.1.2 and 6.1.3) is responsible for designing the Harn Museum programs that engage faculty and students at UF, Santa Fe College, and other area colleges. According to the Harn website, “As Director of Education, Segal leads a remarkable staff of educators who develop innovative and sustainable programs supporting learning for diverse audiences, including families and children and diverse community leaders” (Harn Museum of Art, n.d.).

For many years, Bonnie Berneau, M.S., now retired, was Education Curator of Community Programs and was very much involved with Friends of Elementary Arts. The organization raises funds to support field trips to attend events at the Philipps Center for the Performing Arts and to the Harn Museum by school children in the Gainesville area.

Below are some of the outreach programs conducted by the Harn Museum that serve the African/American Black communities in the Gainesville area.

Exhibitions:

- Exhibition Advisory groups that include members of Gainesville’s African American communities.

Figure 6.1.3: These young children listen to a docent explain a popular painting at the Harn Museum. - Jacob Lawrence Exhibition and Community Day. History Labor Life – Prints of Jacob Lawrence. 2018

- I, Too, Am America. 2019

Programs with schools in largely African American neighborhoods or with diverse populations:

- Early Learning at the Harn Museum.

- Science Night with Florida Museum of Natural History.

- Eastside High class tours.

- Collaborations with Nicole Harris, English and African American History teacher at Gainesville High School: The Harn has facilitated art gallery tours for her classes and plans to collaborate with her in the future on programming.

Outreach:

- Tabling and engagement at Fifth Avenue Arts Festival

- Art kits (individual backpacks with art supplies and projects) distributed through SWAG Family Resource Center and by the Gainesville

- Chapter of the Links (working with Rawlings and Caring and Sharing schools).

- Program with PACE Center for Girls (currently paused due to the pandemic).

- Elementary Art at the Library – program for Head Start Program 4-year-olds to visit the Harn, make art, and enjoy parent engagement activity.

- Program with Reichert House School for at-risk boys (discontinued).

- Tours – free tours for K-12 schools; support for field trip busses; digital educator resources; virtual tours developed and distributed during COVID-19 pandemic.

College of Business

Hector H. Sandoval, Assistant Professor. Director, Economic Analysis Program and Bureau of Economic & Business Research

Sandoval, H. (Project Director). (2018 January). Understanding Racial Inequity in Alachua County. Prepared by the University of Florida Bureau of Economic and Business Research (BEBR). The report provides a baseline of racial disparity data in the county, showing differences between whites and four minority groups: Blacks, Hispanics, Asians, and other. The report was commissioned by Alachua County, Alachua County Public Schools, City of Gainesville, Gainesville Area Chamber of Commerce, Santa Fe College, UF Health, and the University of Florida.

College of Design, Construction, and Planning

Ruth Steiner, Ph.D. Professor, Department of Urban and Regional Planning. Director, Center for Health and the Built Environment

Kristin E. Larsen, Ph.D., AICP. Professor, Department of Urban and Regional Planning. Director, School of Landscape Architecture and Planning

Kathryn Frank, Ph.D. Associate Professor, Department of Urban and Regional Planning

Laura J. Dedenbach, Ph.D., AICP. Lecturer, Department of Urban and Regional Planning

The research included here about Gainesville’s African American communities has often been a collaborative effort among Drs. Larsen, Frank, Dedenbach, and Steiner:

- Frank K., Larsen K., Dedenbach L., Redden T., & Wright, S. (2018). Neighborhoods as Community Assets: The Porters Community, Gainesville, Florida. Grant-funded Research Report (Figures 6.1.4 and 6.1.5).

- Dedenbach, L. J. (2019). A Report on UF-Gainesville Collaborative Engagement Initiatives. Technical Report.

- Larsen, K. (2002). Housing Studio, Duval Neighborhood, Gainesville, Florida. A housing plan for this African American majority community. Unfunded Research.

- Larsen, K. (1990). The Low-Income Housing Tax Credit: Examining an Incentive for the Productive of Affordable Housing in Gainesville’s Pleasant Street District. [Master’s thesis, University of Florida].

- Steiner, R. (Principal Investigator). (n.d.) Safe Routes to School Technical Assistance Phase 2. Department of Urban and Regional Planning. Director, Center for Health and the Built Environment. [Ongoing project].

College of Education

Thomasenia Lott Adams, Ph.D. Professor and Associate Dean for Research and Faculty Development, Office of Educational Research

Dr. Adams’ (Figure 6.1.6) specialty is Mathematics Education in the COE School of Teaching and Learning. She submitted the following publications about research about African American/Black students in Gainesville.

Research with African American female students at Howard Bishop Middle School:

- West-Olatunji, C., Yoon, E., Shure, L., Pringle, R., & Adams, T. L. (2020). Exploring how school counselors position low-income African American girls as mathematics and science learners: Findings from two-year data. In B. Polnick & B. Irby (Eds.), Girls and Women of Color in STEM: Navigating the Double Blind in K-12 Education (pp. 205-225). Information Age Publishing.

- Pringle, R. M., Brkich, K. M., Adams, T. L., West-Olatunji, C., & Archer-Banks, D. A. (2012). Factors influencing elementary teachers’ positioning of African American girls as science and mathematics learners. School Science and Mathematics, 112(4), 217-229.

- West-Olatunji, C., Shure, L., Pringle, R., Adams, T. L., Lewis, D., & Cholewa, B. (2010). Exploring how school counselors position low-income African American girls as mathematics and science learners. Professional School Counseling, 13(3), 184-195.

- West-Olatunji, C., Pringle, R., Adams, T. L., Baratelli, A., Goodman, R., & Maxis, S. (2008).How African-American middle school girls position themselves as mathematics and science learners. International Journal of Learning, 14(9), 219-228.

- Adams, T. L., Laframenta, J., Pringle, R., & West-Olatunji, C. (2010). The positionality of African American girls toward mathematics. Proceedings of the 31st annual meeting of the North American Chapter of the International Group for the Psychology of Mathematics Education, Atlanta, GA., Vol. 5, pp. 477-482.

The following research programs were conducted with an African American teacher and her students at Duval Elementary School:

- Adams, T. L., & Bonner, E. (2018). Distinguishing features of culturally responsive pedagogy related to formative assessment in mathematics instruction. In E. A. Silver & V. L. Mills (Eds.), A fresh look at formative assessment in mathematics teaching: Leveraging connections to tasks, discourse, equity, and more. (pp. 61-79). National Council of Teachers of Mathematics.

- Peterek, E., & Adams, T. L. (2009). Meeting the challenge of engaging students for success in mathematics by using culturally responsive methods. In D. Y. White & J. S. Spitzer (Eds.), Responding to diversity, grades preK-5 (pp. 149-160). National Council of Teachers of Mathematics.

- Bonner, E., & Adams, T. L. (2012). Culturally responsive teaching in the context of mathematics: A grounded theory case study. Journal for Mathematics Teacher Education, 15(1), 25-38. doi: 10.1007/s10857-011-9198-4.

Vicki Vescio, Ph.D. Clinical Associate Professor, School of Teaching and Learning

Dr. Vescio’s doctoral dissertation, awarded by the University of Florida (2010), was about 4th grade African American boys and their identification with academics. When asked about this research, she answered as follows:

I came to this topic because I had spent a lot of time working in the East side elementary schools during my doctoral studies and was disheartened by patterns that I saw in how Black boys were being treated…It was an enriching experience for me, but it was not without its difficulties as I struggled with “taking” from the boys and the community for my research and wondered what I was giving back. In recent years, I have been trying to find the 6 boys whom I worked with who are now young college-aged men. I have had success in connecting with people who know where a few of them are but I have not actually had the chance to connect with any of the young men who were in my study when they were 10 years old—although I will continue to try (Vescio, 2018).

College of Engineering

Juan E. Gilbert, Ph.D. The Banks Preeminence Chair in Engineering, Department of Computer & Information Science & Engineering. (CISE)

Dr. Gilbert’s research and outreach have not focused specifically on the Black communities in Gainesville. However, he specializes in human-centered computing and artificial intelligence and has committed himself to increasing diversity in the STEM field and supporting and empowering other Black scientists in the scientific community. He created a set of guidelines to structure and support inclusion in the CISE department at UF. One of the guidelines is to engage the local community. Seek opportunities to engage the local Black community in research and development. Offer technology learning classes, provide broadband access, etc. Work with them as partners not as subjects.

Like many in the Gainesville Black communities, Dr. Gilbert was the first person in his family to go to college and he was the only African American in his Computer Science Ph.D. program at the University of Cincinnati. This and other experiences have led him to become not only an advocate, but a leader at UF and nationally. According to his website, in 2006 Gilbert launched Applications Quest, a software tool which uses artificial intelligence in evaluating and comparing student’s applications to increase diversity without sacrificing quality. Most recently, he created the Prime III Software Voting System as a model to make elections more secure, equitable, and inclusive. His inventions were used in recent elections in several states. In order to help students to expand their awareness of opportunities in computer science engineering, he regularly speaks to students at local schools, and particularly aiming to inspire African American/Black students.

Christina Gardner-McCune, Ph.D. Assistant Professor, Computer & Information Science & Engineering

Dr. Gardner (Figure 6.1.7) has been engaged in the African American/Black Communities in Gainesville over the past six years since she came to UF. She has also involved her graduate students in project design and implementation. In response to our inquiry, she submitted the following research publications and outreach service projects.

Publications that have resulted from this community engagement:

- Aggarwal, A., Gardner-McCune, C., & Touretzky, D. S. (2017, March). Evaluating the effect of using physical manipulatives to foster computational thinking in elementary school. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM SIGCSE Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education (pp. 9-14).

- Rivera, R., Gardner-McCune, C., & McCune, D. B. (2017, June). Engagement in Practice: University & K-12 Partnership with Robotics Outreach. In 2017 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition.

- Jester, E. (2014, December 11) Students get early glimpse at the joy of computer coding. Gainesville Sun. https://www.gainesville.com/article/LK/20141211/news/604159224/GS

- Isaac, J., Yerika Jimenez, Y., and Gardner-McCune, C. (2020). (In Press) Engaging 4th and 5th Grade Students with Cultural Pedagogy in Introductory Programming. 2020 Research on Equity and Sustained Participation in Engineering, Computing, and Technology (RESPECT), Portland, Oregon.

Outreach events reported by Dr. Gardner-McCune:

- In 2014, we collaborated with Eastside High School and conducted an all-day Hour of Code for CS Education Week for over 1000 students.

- In 2015, we offered a Cybersecurity Summer Camp in collaboration with Gainesville Parks and Recreation at McPherson Community Center. We had 15 AA students grades 4th through 7th participate.

- In 2015-2016, I participated in the Alachua County School District’s Vex Robotic program training undergraduate STEM (mostly engineering) students in how to teach robots. We were in several of the elementary and middle schools including Lincoln Middle School.

- In 2016, we ran a six-week after-school program in collaboration with the Passage Christian Academy with 10 African American students in elementary and middle schools.

- Two of my Ph.D. students, Yerika Jimenez and Joseph Isaac, Jr., have run six-to-eight week summer programs in 2019 and 2020 for 50 4th and 5th graders at Caring and Sharing Learning School’s STEM Summer Camp.

- From 2015-2019, I have worked with eight African American small businesses owners and entrepreneurs to build web applications for their businesses through my software engineering course.

College of Health and Human Performance (CHHP)

Bertha Cato, Ph.D. Associate Professor Emeritus, Department of Tourism, Recreation, and Sport Management

As the principal investigator, Dr. Cato received a $434,000 grant from the U.S. Department of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevent and the state of Florida Juvenile Justice Department. Known as Project WISE-UP this case study used a logic model to plan and evaluate an intervention project for African American students at a Gainesville middle school. The aim of the project was to reduce the risk of using drugs and alcohol and becoming involved in criminal activities. The study considered a continuum of integrated interactive activities that comprised the students’ environment: community, school, peer group and family. Two of the publications from this research:

- Chen, W. W., Cato, B. M., & Rainford, N. (1999, January). Using a Logic Model to Plan and Evaluate a Community Intervention Program: A Case Study. International Quarterly of Community Health Education. Retrieved from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.2190/JDNM-MNPB-9P25-17CQ

- Cato, B. (2006). Enhancing Prevention Programs’ Credibility through the Use of a Logic Model. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education. 50(3), 8-20.

Delores C. S. James, Ph.D. Associate Professor, Department of Health Education and Behavior

Dr. James’ (Figure 6.1.8) research lays the groundwork for understanding how African Americans use technology to improve their health, their motivations for (and barriers to) to participation in mHealth interventions, as well as recruitment strategies and desirable program elements for mHealth interventions. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) defines mHealth as “the use of mobile and wireless devices (cell phones, tablets, etc.) to improve health outcomes, health care services, and health research (n.d.).” Dr. James’ current research focuses on creating and sustaining online health communities. She created a blog and website, Keep It Tight Sisters, https://keepittightsisters.com, and Facebook page focused on Black women’s health issues. She also uses the social media platform Pinterest as a digital clearinghouse for resources on self-care and wellness. In response to our inquiry about her research and service involving the Black/African American communities in Gainesville, Dr. James sent an extensive list of publications conducted in Gainesville over more than 20 years. In addition to her academic research and service, she has served the community as Chair of the Affordable Housing Advisory Committee for the City of Gainesville.

Five topic areas of her research are presented below. Because of space limits of this chapter, two of Dr. James’ publications in each topic were selected.

Health, Social Media, and Technology Use and Access among African Americans:

- James, D.C.S. (2019). Willingness of African American men to participate in mHealth weight management programs. International Journal of Health Sciences, 7(4), 13-21.

- James, D.C.S., Harville, C. (2019). Online Health Information Seeking among African Americans. International Journal of Health Sciences, 7(3), 19-32.

Health Issues among African American Women:

- James, D.C.S., Harville, C. (2017, June 1) Electronic publication ahead of print: Smartphone Usage, Social Media Engagement, and Willingness to Participate in mHealth Weight Management Research among African American Women. Health Education & Behavior. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1090198117714020

- James, D.C.S., Pobee, J., Brown, L., and Oxidine, D. Using the Health Belief Model to Develop Culturally Appropriate Weight Management Materials for African American Women. Journal of the American Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2012 112:664-670.

Health Literacy and eHealth Literacy and African Americans. Health literacy is a key social determinant of health:

- James, D.C.S. and Harville, C. (2016). Assessment of eHealth Literacy, Online Help-seeking Behavior, and Willingness to Participate in mHealth Chronic Disease Research among African Americans, Florida, 2014-2015. Preventing Chronic Disease, 13, https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd13.160210

- James, D.C.S., Harville, C., and Efunbumi, O. (2015). Health Literacy and Online Health-Seeking Behaviors among African Americans. The Health Education Monograph Series, 32(2), 22-32.

Cultural Influences on the Diets of African Americans:

- James, D.C.S. (2009). Cluster Analysis Defines Distinct Dietary Patterns for African American Men and Women. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 109(2), 255-262.

- James, D.C.S. (2004). Factors Influencing Dietary Intake among African Americans: Application of a Culturally Sensitive Model. Ethnicity and Health, 9(4), 349-368.

Development of Culturally Relevant Health Education Messages and Programs:

- James, D.C.S. (2013). The Right Size for Me: A Weight Management Guide for African American Women. The American Dietetic Association.

- James,D.C.S. (2000). The Temple Project: A Spiritually Based Health and Wellness Curriculum. Florida Department of Health.

College of Liberal Arts and Sciences

Patricia Hilliard-Nunn, Ph.D. Senior Lecturer, African American Studies Program

Dr. Hilliard-Nunn (1963-2020) passed during the Fall Semester. In tribute to her organized by the College of Liberal Arts & Sciences (CLAS), she was lauded for bridging the gap between the University and the local communities through her research and service activities. She worked in several different media. Her research addresses Africana history and culture, media representations, the history of Blacks in Gainesville and Alachua County, lynching in Alachua County, Black Seminoles, and African Cultural Retentions. Her most recent article, “The Agency of Black Female Protagonists in Haile Gerima’s Bush Mama and Sankofa,” is in African American Cinema Through Black Lives Consciousness (Reid, 2019).

She researched and produced 100 Years of Gracious Dignity: The Chestnut Funeral Home (Gainesville, FL) [DVD] (2014), 45 Years of Triumph and Struggle: African American Studies at UF [DVD] (2014), and First Footsteps: The Struggle for Racial Desegregation at UF [DVD] (2012) for the Levin College of Law. She also researched and wrote the script for In the Shadow of Plantations, a video about enslaved laborers in Alachua County that was produced by the Alachua County Communications Office. With a mini grant from the Florida Humanities Council, she collaborated with Kenneth Nunn to write and produce the Sankofa Black History Flash radio spots which aired on Magic 101.3 in Gainesville, FL. She served as the first host of the Alachua County NAACP public affairs radio program called The Voice.

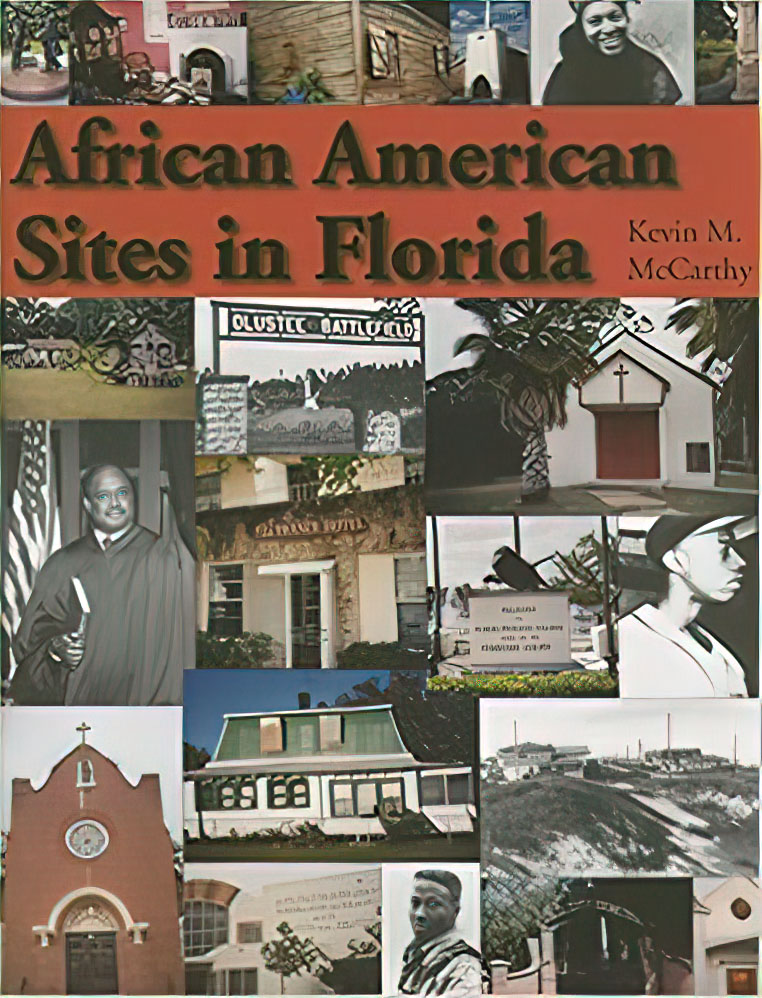

Kevin M. McCarthy, Ph.D. Professor Emeritus, Department of English

Dr. McCarthy has published over 35 books, the majority of which deal with Florida history and culture. Relevant to this chapter are his books on African American History and Culture (Figures 6.1.9 and 6.1.10).

- McCarthy, K. M. (2019). African American Sites in Florida. Pineapple Press, Inc. (Original work published 2014).

In this book, Dr. McCarthy alphabetically organizes Florida’s 67 counties. Alachua County—in which Gainesville is located—is the subject of the book’s first chapter. It covers major historical figures such as Josiah Walls, the first Black Congressman from Florida, after whom the Supervisor of Elections office in Gainesville—among other things—is named. - McCarthy, K. M. (1995). Black Florida. Hippocrene Books, Inc.

This book is a city-by-city guide to churches, schools, homes, and other significant sites in more than 70 towns across Florida, including Gainesville.

Figure 6.1.10: Gainesville’s African American community is featured in Dr. McCarthy’s book that takes a geographical tour of Florida’s counties. - Jones, M. D. & McCarthy. K. M. (1993). African Americans in Florida. Pineapple Press.

This book tells the story of 400 years of African American presence and contributions to the state beginning with “Estevanico the Black” who arrived in 1528 as an explorer to 20th century discussing Floridians such as musician Ray Charles and author Zora Neale Hurston. - Jones, M. D. & McCarthy, K. M. (2014). Teachers’ Manual for African Americans in Florida. Pineapple Press, Inc. (Originally published 1993).

- White, A. and K. M. McCarthy. (2012). Lincoln High School: Its History and Legacy. Pineapple Press, Inc.

Heidi Lannon, Ph.D. Adjunct Professor, Department of Geography

Dr. Lannon worked on a four-year National Science Foundation grant to recruit, retain, and transfer local high school students from underrepresented groups, including but not exclusively for African Americans in the local community. The grant was a joint effort between UF and Santa Fe College. Students took basic geography courses, did research with UF faculty, and participated in a summer internship at the Orlando Science Museum. Four students currently enrolled in the UF Geography Department were participants in the NSF grant. She is currently working with an African American student from Gainesville who graduate from Santa Fe College and will apply for admission to UF.

Dr. Lannon is developing a service-learning course for the UF Geography curriculum. She believes that it has much potential for students taking the course to work with local African American organizations and encourage youth members to consider careers in geography. The aim of service-learning is to extend traditional classroom-based education by placing students into the community. The objectives of the class (GEO/GEA 2000 or 3000) are: enhanced civic responsibility, citizen engagement with geography, awareness of career interests and opportunities in service, science, public policy, and the environment. Focus areas include Medical Geography/Global Health, Sustainability/Global Environmental Change, Geopolitics, and the Global Economy.

Dr. Lannon also assists geography teachers in local high schools, particularly those that offer AP Geography courses such as P.K. Yonge, Eastside, and Santa Fe.

Gabriela Hamerlinck, Ph.D. Lecturer, Department of Geography

Dr. Hamerlinck and Graduate Student Sarah VanSchoick have started an outreach initiative for local K-12 students. The aim is to increase enrollment in Geography Department and to reach out to students from diverse backgrounds. The project will connect with local schools, clubs, and programs to provide resources to inform the students about majors and careers in geography.

Paul Ortiz, Ph.D. Professor, Department of History and Director of the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program (SPOHP). See also Chapter 3.

The mission of SPOHP is to gather, preserve, and promote living histories of individuals from all walks of life: https://oral.history.ufl.edu.

The Proctor Program was founded in 1967 by University Historian Dr. Samuel Proctor. SPOHP engages students, scholars, and local communities throughout the world in gathering, preserving, and promoting living history through academic publications, public programs, electronic media, and other forums in order to document the human condition. Its motto: “One community, many voices.”

The Joel Buchanan Archive of African American Oral History is an archive of 1,000+ oral history interviews conducted with African Americans in Alachua County, as well as Florida, the Gulf South, and other parts of the nation. The Joel Buchanan collection is one of the premier archives of African American oral history in the United States. It also includes scores of public programs, symposia on Black history, oral history workshops, documentaries, and podcasts on many facets of African American Studies. The collection has been used by scholars, students, film makers, radio producers and many others: https://oral.history.ufl.edu/projects/aahp.

Carolyn M. Tucker, Ph.D. Professor, Department of Psychology.

Dr. Tucker (Figure 6.1.11) has over 40 years of experience in conducting community engaged and patient-centered research to promote health and culturally sensitive health care, particularly in racial/ethnic minority, low-income, and medically underserved communities. According to her website, she is the founder of the culturally sensitive Health-Smart Program to Prevent and Reduce Obesity and Related Diseases. She uses an academic-community partnership approach and the community-based participatory research model.

She has over 140 published, refereed, research articles that span from 2020 to 1980. Her current research was featured on the UF Website in April 2020: “Golden Years. New Program Looks to Improve Lives of Seniors in Need.” Led by Dr. Tucker, this community-based program provides resources that empower participants to improve their own mental, physical, and spiritual health (Figure 6.1.12). This project was initially launched in the Jacksonville area. Much of her life-long research and clinical work have embraced the Gainesville communities, both urban and rural.

Dr. Tucker’s research publications span over 20 pages. A small sample of her most recent publications is provided here.

- Tucker, C. M., Roncoroni, J., & Buki, L. P. (2019). Counseling Psychologists and Behavioral Health: Promoting Mental and Physical Health Outcomes. The Counseling Psychologist, 47(7), 970-998.

- Tucker, C. M., Kang, S., & Williams, J. L. (2019). Translational research to reduce health disparities and promote health equity. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 5(4), 297-301.

- Tucker, C. M., Kang, S., Nmezi, N. A., Linn, G. S., Disangro, C. S., Arthur, T. M., & Ralston, P.A. (2019). A culturally sensitive church-based health-smart intervention for increasing health literacy and health-promoting behaviors among Black adult churchgoers. Journal of health care for the poor and underserved, 30(1), 80-101.

- Wall, W. A., Tucker, C. M., Roncoroni, J., Guastello, A. A., & Arthur, T. M. (2019). Clinical staff’s motivators and barriers to engagement in health-promoting behaviors. Journal for Nurses in Professional Development, 35(2), 85-92.

- Roncoroni, J., Tucker, C. M., Wall, W.A., Wippold, G., & Ratchford, J. (2019). Associations of health self-efficacy with engagement in health-promoting behaviors and treatment adherence in rural patients. Family & Community Health, 42(2), 109-116.

- Wippold, G.M., Tucker, C. M., Smith, T., Ennis, N., Kang, S., Guastello A.A., Morrissette T.A., Arthur, T.M., & Desmond, F.F. (2019). An examination of health-promoting behaviors among Hispanic adults using an activation and empowerment approach. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, 13(1), 7–18.

- Tucker, C. M., Roncoroni, J., Wippold, G. M., Marsiske, M., Flenar, D. J., & Hultgren, K. (2018). Health self-empowerment theory: predicting health behaviors and BMI in culturally diverse adults. Family & Community Health, 41(3), 168-177.

- Tucker, C. M., Smith, T.M., Hogan, M. L., Banzhaf, M., Molina, N., & Rodriguez, B. (2018). Current demographics and roles of Florida Community Health Workers: Implications for future recruitment and training. Journal of Community Health, 43(3), 552-559.

- Tucker, C. M., Roncoroni, J., Wippold, G. M., Marsiske, M., & Flenar, D. (2018). Health self-empowerment theory (HSET): Predicting health behaviors and BMI in culturally diverse adults. Family & Community Health, 41(3), 168-177.

- Wippold, G., Tucker, C. M., Smith T. M., Rodriguez, V., Hayes, L., & Folger, A. C. (2018). Motivators of and barriers to healthy health-promoting behaviors among culturally diverse middle and high school students. American Journal of Health Education, 49(2), 105-112.

Brian Cahill, Ph.D. Lecturer, Department of Psychology

Dr. Cahill established a year-long internship with the Gainesville Public Defenders Office, exclusively for Psychology undergraduate students. Students will be working directly with lawyers who represent low-income clients facing criminal charges in Alachua County, both misdemeanors and felonies.

Research by faculty members is ongoing and continuous. Service activities respond to both faculty interests and community initiatives and needs. Therefore, information in this publication can be updated as faculty and community engagement inevitably continue. These activities are the human faces of the mission of the University of Florida as a public institution.

Chapter 6, Section 1 Study Questions

1. Discuss in 200-300 words what you consider to be three major substantive issues in this section.

2. How relevant are the research and services cited in this section to your studies and future career?

3. What is your overall assessment of the content in this section?

Section 2: Educational Outreach – The Upward Bound Program at UF by Gwenuel W. Mingo

Since the mid-1960s, institutions of higher education like the University of Florida have facilitated federally funded programs designed to serve low-income students from their local communities. Three initial programs were known as the TRIO programs: Upward Bound, Talent Search, and Supportive Educational Services. The Upward Bound Program was first and was created out of the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964 and the War on Poverty (“History of TRIO Programs,” 2020). The Program serves students from low-income households and families in which neither parent holds a Bachelor’s degree. Upward Bound (UB) is designed to provide the support necessary for low-income students to succeed in their high schools, graduate, then enroll in and earn a degree at a post-secondary institution.

From April of 1974 until he retired in June of 2003, Dr. Gwenuel W. (G.W.) Mingo directed the Upward Bound Program at UF. The reflections presented here represent that period. (For Directors after Dr. Mingo, see Notes #2). In applying for federal funds for this program, post-secondary institutions had to submit a proposal to the U.S. Department of Education (USDOE) specifying how they would provide academic instruction, counseling, tutoring, and educational and cultural activities for the students to facilitate success.

Funded institutions were not required to show how parents would be involved in Upward Bound, but parents played a critical role in the Program at the University of Florida, where Mingo created specific objectives regarding parental involvement. The Parent Advisory Board as outlined in Mingo’s proposal reviewed policies, carried out fundraising activities, advocated for the Program and shared beneficial information to all of the families in the Program. The Parent Advisory Board also shared strategies and information between other Upward Bound Programs throughout the nation.

The Parent Advisory Board was designed to help the Director accomplish the Program’s objectives more efficiently by providing guidance in locating and utilizing community resources. The Advisory Board consisted of elected officers, mainly a President, Vice President, Secretary, Assistant Secretary, Treasurer, Assistant Treasurer, and Chaplain. The officers and other parents were empowered and educated by the Director on matters impacting their children both in the classroom and in the community. The Parent Advisory Board was the primary source of community engagement between the University of Florida and the Black Communities in Gainesville. Although Upward Bound is open to all students, the majority of participants were Black.

- Parents of students in the University of Florida’s Upward Bound Program’s engagement in the community included:

- Assisting in the mobilization of community resources for Upward Bound activities.

- Serving as the liaisons between the Program and community personnel.

- Recruiting volunteer services from individuals and agencies in the community.

- Assisting in finding solutions for families with problems such as housing, welfare, transportation, employment, legal, and social issues.

- Advising the University on issues that were confronting the Program.

- Assisting with the grant application.

- Providing suggestions for Program improvement.

- Suggesting ways of expanding the influence of the Program in the community.

- Conducting UB events at churches in the community.

- Conducting fundraising activities in the community.

During each academic year, parent meetings were scheduled at least once per month where the agenda items often included discussing Upward Bound Program activities, attending workshops, participating as chaperones on education and cultural field trips, as well as planning and implementing fundraising activities. The Parent Advisory Board was effectively leveraged by the Director to help minimize challenges by dealing with hostile parents and students, disciplining students who broke rules, discouraging drug and alcohol use, motivating unmotivated students, informing uninformed community members about the merits of the Program, and dispelling any negative publicity. Knowing the data, especially for the support of students in minoritized communities, and believing that parents should play an active role in the education of their children, the Director encouraged parents to be effective educational team members. This included partnering with teachers at Upward Bound and the high school their child attended, as well as the Upward Bound Staff (Director, Coordinator, and Counselors), and the students.

Expanding the Reach Through Fundraising

Mingo worked to establish a rapport and maintain open lines of communication with the parents over the years, which served as the basis for a helpful partnership. Parents and students had a clear understanding of the educational and cultural goals and objectives of the University of Florida’s Upward Bound Program and they worked to help the Director achieve those goals by raising additional funds to supplement the resources from the federal government, creating avenues for their students to gain greater exposure. Table 6.2.1 lists annual fundraising activities that were executed by the UB Parent Advisory Board.

|

Month |

Fundraising Activities |

|

September – November |

Worked the Concession Stands at University of Florida Football Games Sold Sweet Potato Pies during Thanksgiving |

|

December |

Assembled Financial Aid Packets for the University of Florida |

|

January |

Conducted a Gospel Jubilee at Mt. Olive A.M.E. Church in Gainesville |

|

March |

Worked the Concession Stands at the Gator Nationals |

|

April |

Held a Fashion Show in the UF and P.K. Yonge Auditoriums Sold Candy tins |

|

May |

Held a May Day Festival at T.B. McPherson Center and Citizen’s Field |

|

June |

Held Car Washes throughout the city |

Mingo encouraged the parents to attend seminars and workshops at the University of Florida specifically targeted for the students including College/Career Fairs, Financial Aid Workshops or Recruitment Conferences that Upward Bound students attended. Parents were also taught techniques of effective communication so they could advocate on behalf of their students, they were given clarity on high school course requirements and college preparation strategies so their children would not only attend college, but successfully graduate from college. The exposure to higher education provided by Upward Bound was helpful in educating not only students—many of whom would go on to become first-generation college students—but also preparing parents to support their students’ pursuit of higher education. By enthusiastically sharing the benefits—academic preparation, cultural expansion, and overall student success—gained through participation in Upward Bound, the Parent Advisory Board served as an effective recruitment vehicle for other parents and students in the community who were not familiar with the Upward Bound Program. As partners within the community, parents also assisted local groups in increasing attendance at events by distributing flyers and calling parents and students to publicize their programs.

The Parent Advisory Board and the Director regularly conducted workshops on parental involvement in high school (which could contribute to academic success), college admission procedures, and applying for financial aid. Recognized beyond the local arena for their strong impact with the program, occasionally, the Director would take a group of parents to State, Regional, and National TRIO Conventions to participate as presenters on parental involvement in the Upward Bound Program. The parents provided their own funding for the trips to the conventions.

Maintaining a clear and distinct financial separation between the Parent Advisory Board and the Upward Bound Program, the parents’ funds were in a checking account at a local bank where they deposited funds from their fundraising events. The Treasurer kept records of all monies received as well as all monies dispersed. The President, Secretary, and Treasurer had the authority to sign checks; two signatures were required for any checks written by the Treasurer.

Political Advocacy for Federal Funding and Support

During the 1982 academic year, Mingo submitted the proposal to the U.S. Department of Education (USDOE) for Upward Bound funding only to learn that the Program would not be funded. The Dean of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences at the University of Florida, Charles F. Sidman, was informed of this matter and he informed Robert Bryant, the Vice President of Academic Affairs. Bryant responded, “I do not believe it is appropriate to use general revenue dollars to fund a Program that has as its participants people who are not students at this university or persons who may never enroll as students at this university.” He went on to say that the University should make no attempts to restore the funding for the Upward Bound Program.

After calling the USDOE many times to inquire about the proposal, specifically the scores earned for each evaluated objective and the data which justified the need for the Program, the USDOE would not provide any information. It was suggested that the Director go to Washington, D.C. to meet with someone face-to-face. Understanding the importance of the Upward Bound Program to the community and the critical partnership with the parents, not only did Mingo prepare to go to Capitol Hill, but he also involved the parents.

Two parents, Mrs. Lucille Miles and Mrs. Deloris Johnson, who served as the Vice President and Treasurer of the Parent Advisory Board respectively, accompanied Dr. Mingo to Washington to meet with the Program Officer at the USDOE, who was responsible for the University of Florida Upward Bound Program. While in Washington, they went to the offices of Florida Congressional members including Senator Lawton Chiles to solicit their help before going to meet with the Program Officer. The parents prayed for guidance before the meetings. The parents were professionally dressed, and they asked direct and logical questions of those they met with. The USDOE officials thought that they were Upward Bound staff members. They were surprised to find out that parents used their limited resources to travel to Washington and obtain an explanation for the retraction of funding for the University of Florida’s program.

The two Parent Advisory Board leaders—representing many other parents back in Florida—asked questions about the scoring process and how USDOE determined there was no longer a need for the Program in the Gainesville area. The parents cited the names of students from Gainesville who had gone to college who were now teachers, engineers, pharmacists, and productive citizens. The parents also conducted some research on their own while they were in the USDOE facility, which was used to appeal the decision to not fund the University of Florida’s Program. After two days in Washington, the Director and parents returned to Gainesville and immediately sent a written appeal to the USDOE regarding the funding, which was successfully approved. The University of Florida’s Upward Bound Program had been saved and the Parent Advisory Board played a significant role in this victory.

The parents in UB were active and involved citizens who understood the political and philosophical battles surrounding the funding of UB Programs, so they did not hesitate to participate in the letter writing campaigns or to place calls to the offices of Representatives. The Upward Bound parents at the University of Florida were definitely fighters seeking to expand the funding and benefits of all Upward Bound Programs. The experiences of the Upward Bound parents in writing to their senators and representatives concerning funding of the program was a real-life civics lesson that inspired and empowered them to use their voices in other ways to benefit their neighborhoods.

In 1987, President Reagan proposed a 44% cut to the funding of the Upward Bound Programs around the nation (Eksterowicz & Gartner, 1990). Students and their parents wrote letters asking their Congresspersons to increase funding for these programs rather than cutting them, as President Reagan proposed. With an introduction by Senator Lawton Chiles, G.W. Mingo made his first appearance before the Senate Subcommittee on Appropriations on May 5, 1987 in Washington D.C. testifying in support of the TRIO Programs and helping influence a positive funding outcome for Upward Bound Programs (see Notes #1). Galvanizing support of students, parents, and community members, the letter-writing campaigns of all Upward Bound Programs nationwide ultimately proved effective in increasing funding to the Programs. Both the Senate and House passed a Continuing Resolution for a 16.7% increase in the funding of the Upward Bound Programs for the 1988 Fiscal Year. While his testimony helped make the case for funding, Mingo is clear that the bombardment of heartfelt letters written by parents to their Congresspersons describing the impact of Upward Bound on their family undoubtedly had a greater effect than that of one person testifying before a committee.

Encouraging Political Involvement

In this day and time of volatile political activity, it is unthinkable and unwise not to write or call your Congresspersons to solicit their support for keeping legislation and appropriation favorable to the Upward Bound Programs. As modeled by Dr. Mingo during his tenure at the University of Florida, Program Directors should not be the only ones emailing, calling, texting, and faxing the Congressperson about Upward Bound matters. They should also enroll students, parents and guardians of the students, and friends of the Upward Bound Program to contact the Congresspersons from their districts and advocate for Upward Bound.

Mingo found that the first step in empowering parents to become politically active was getting them registered to vote. As registered voters, parents can be more effective advocates for political change. Upward Bound Directors and parents of the students can establish an effective political advocacy team in conjunction with the Upward Bound educational team.

Parents must be encouraged by the Directors to involve themselves in the political processes in their communities. Parents should be involved in political groups at the lowest levels, in areas such as crime watch groups, parent/teacher associations, school boards, city and county commissions, etc. Directors and parents should find ways to utilize their talents to form educational and political teams for the purpose of enhancing the services rendered to their children. A team consisting of parents and UB personnel who advocate for better education in their school districts can also be effective advocates for education on the national level.

Cultural Exposure Within and Beyond Gainesville

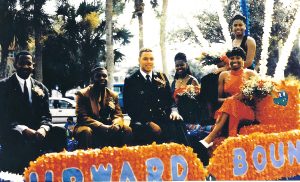

Participation in the Gator Homecoming parade was a major activity that the parents used to publicize the Upward Bound Program in the Gainesville community. Each year, the Program had a float in the parade with Mr. and Ms. Upward Bound and their royal court dressed in gowns and suits riding on the float, looking very distinguished. The parents secured a trailer from contacts in the community and the Chestnut Funeral Home donated garage space to allow the students and parents to build the float—in case of inclement weather. One year, the UF Student Government Association decided not to let the Upward Bound Program participate in the parade, and that made the parents upset. The Student Government Association was going to let groups not affiliated with the University (such as the Shriners) participate, but not the Upward Bound Program, which is an official University of Florida program. The parents and the Director told Student Government officials that if Upward Bound was excluded then the parade should be cancelled. After some heated discussion, the SGA allowed the UB Program back in the parade.

The Upward Bound parents were not only focused on helping to make a difference and positive impact in the Gainesville community, but they were also cognizant of helping others outside of their local community. In 1992, when Hurricane Andrew hit South Florida, the Upward Bound Parent Advisory Board contributed $800 to the University of Miami’s Upward Bound Relief Fund to help Upward Board families that suffered losses. In 1995, the parents sent $1,600 to the U.S. Virgin Islands to help Upward Bound families that were devastated when Hurricane Marylin hit their island.

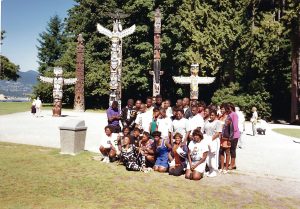

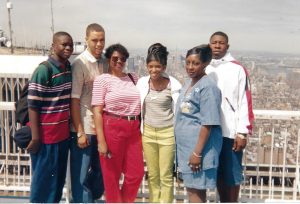

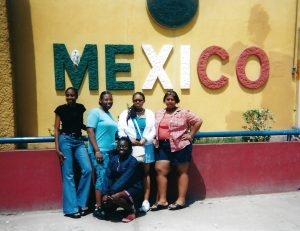

Every summer, students from the University of Florida’s Upward Bound participated in an educational and cultural field trip to various states around the country, Puerto Rico, Canada, Mexico, or the Caribbean (See Figures 6.2.1. to 6.2.4). Prior to departing on these trips, participants were given preparatory instructions or experiences to acquaint them with the people and their culture. These trips to exhilarating, exotic, and enchanting destinations were planned by the Director, but the students and parents voted on whether they wanted to go on the trips. However, without the fundraising efforts of the parents, the trips would have been limited to a 300-mile radius and students would not have gained the exposure the Director desired.

Upward Bound students at UF travelled to the following destinations:

- Nassau, Bahamas – 1980, 1984, 1985, 1993, 1996

- Jamaica – 1986, 1999

- Puerto Rico – 1987, 1990, 1995, 2002

- U.S. Virgin Islands – 1990, 1995, 2002

- Florida to California (Cross-Country Tour) – July 17th – 31st, 1988

- Key West – 1982, 1984, 1991

- Seattle and Vancouver – 1991

- New York, Montreal, Quebec – 1989, 1992, 2000

- Tuskegee, Selma, Montgomery – 2000

- California, Mexico, Nevada – 2001

Whenever it was possible during the field trips, the Director made sure students stopped at institutions that had Upward Bound Programs. If the stop included an overnight stay, they coordinated with the directors of those programs to meet with their students and have a social activity. The following provides insight into the types of educational and cultural activities students engaged in during a domestic summer field trip.

Fourteen Days on the Road – A Cross–Country Tour

This 14-day “Marathon Tour” went from Florida to Alabama to Tennessee to Missouri, Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, California, Texas, Mexico, Louisiana and then back to Gainesville, Florida. It was a trip to remember, and included stops in historic Tuskegee, Alabama, where students and parent chaperones toured Tuskegee University and the George Washington Carver Museum. In Memphis, all were respectfully silent when we visited the Lorrain Hotel where Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated.

Visits to colleges that students might want to apply included LeMoyne-Owen College in Memphis, Metro State Park City College, University of Colorado, the Community College of Denver, the Air Force Academy, Pike’s Peak Community College, Colorado College, Northern Arizona State University, Arizona State University, University of Nevada-Las Vegas, and University of Southern California. Then the tour headed back east to Texas Southern University and Huston-Tillotson University. Then Dillard, Loyola, and Xavier Universities in New Orleans.

Highlights of the trip included the Grand Canyon, Pike’s Peak, Chinatown, Beverly Hills, Los Angeles Philharmonic Concert, and a live TV viewing of the hit daytime program Family Feud. Then back to the Alamo in San Antonio, the high-tech Motorola Plant in Austin, and the Superdome in New Orleans.

The extensive coast-to-coast trip wound back to Panama City and Tallahassee before arriving on the 14th day in Gainesville.

This cross-country trip would not have been possible if it had not been for the Upward Bound parents. They raised a considerable amount of money for the trip and they served as outstanding chaperones for the duration of the 14 days on the road. In addition to the two Upward Bound staff members, a total of five parents served as chaperones on this trip. In order to develop a strong Upward Bound Program, Mingo found that it was important to mobilize and utilize a wide variety of community resources including parents and guardians to facilitate an efficient and effective program.

Conclusion

As a clear marker of the program’s success, 85% of the over-3,000 high school students from low-income or first-generation college backgrounds who participated in the University of Florida’s Upward Bound Program while Mingo was the Director attended colleges and universities throughout the United States, with some electing to attend the University of Florida. Parental involvement made a difference not only while their children were high school students taking weekend and summer academic enrichment classes on the University of Florida campus, but it also prepared them to support their students as they pursued higher education. Some of the parents became inspired by their children to enroll in college, which resulted in many older adults earning Associate’s and Bachelor’s Degrees and establishing new legacies of academic achievement in their families. Some went on to work in local education systems as teacher’s aides and office administrators in the Alachua County Public Schools.

The Upward Bound Parent Advisory Board at the University of Florida served as a model for increasing relational educational and community engagement for the Alachua County Public Schools, Santa Fe Community College, and the University of Florida to follow. Each year, parents, students, and staff cooperated in decorating a float in the UF Homecoming Parade which showcased Mr. and Miss Upward Bound (Figure 6.2.5 below). Upward Bound parents and key individuals in the community formed a natural communication bridge that created positive social capital for the educational institutions in the local area.

The Upward Bound parents functioned as an unofficial liaison from one Program at the University to churches, clubs, schools, and many social and fraternal organizations in Gainesville, particularly within the Black community. The Parent Advisory Board provided the University of Florida with a great opportunity to connect with the Black community, but the University failed to recognize and utilize the talents and skills of the parents. Many educators and administrators tend to bypass direct contact with parents and did not solicit their input in matters related to educating their children.

During his tenure as Director, G.W. Mingo educated and empowered parents by including them in the planning and operation of the Program. Many of the parents personally benefitted from their involvement, with some becoming inspired to further their own educational pursuits and following in their children’s footsteps to earn Bachelor’s Degrees, which enabled them to increase their incomes with better job opportunities.

The parents in the University of Florida’s Upward Bound Program through the Parent Advisory Board operated as an integral and critical component of the Program. The Advisory Board reviewed Program policies, carried out fundraising activities, and shared information beneficial to all families in the Program through a variety of official and semiofficial activities. The parents have been a great asset and a salient tool in fighting funding cutbacks. Their advocacy on the state, local, and national level has resulted in greater benefits for the low-income children and families connected to TRIO Programs in the United States.

Overall, the parents of the University of Florida’s Upward Bound Program were dedicated advocates and partners in the educational, cultural, and community activities in Gainesville and the surrounding counties. Thus, the impact of the program on Black and low-income families and the Gainesville communities was significant. During the period of more than 38 years when Upward Bound was funded at the University of Florida, over 3,000 students were enrolled in this college preparation program.

Notes

- G.W. Mingo testified before the U.S. Senate on two occasions in support of TRIO Programs on May 5, 1987 and June 7, 1988. The testimonies are recorded with the Department of Labor, Health and Human Services, Education and Related Agencies Appropriations in H.R. 3058 and H.R. 4783 during the first and second session of the 100th Congress for fiscal years 1988 and 1989 (the fiscal years end in September).

- Dr. Mingo was succeeded as Director by Beatrice Peak (2003-2004), and Dr. Barbara McDade Gordon (2004-2012), who served with shared appointment as a faculty member in the Department of Geography and Center for African students. The Upward Bound Program was not funded by the USDOE after 2012.

Chapter 6, Section 2 Study Questions

1. Based on this essay and related materials—what, in your opinion, is the value of Upward Bound in American higher education?

2. Conduct interviews with at least three students to get their views about programs such as Upward Bound.

3. To what extent did the Upward Bound Program contribute to the University of Florida’s mission as a public institution?

References: Chapter 6, Section 2

“History of Federal TRIO Programs.” Retrieved August 10, 2020, from https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ope/trio/triohistory.html.

Eksterowicz, A. J. and Gartner J. D. (1990, July). Funding the Department of Education’s Trio Programs. Public Affairs Quarterly, 4(3), 233-247.

Section 3: Religious Connections – The Pentecostal Initiative at UF and the Community by Sherry Sherrod DuPree

The role of community engagement in developing information sources in the area of African American Studies, including historical primary sources, has not been well documented by scholars. This case study on community engagement focuses on the University of Florida’s (UF) interactions with the African American Eastside communities in Gainesville, especially Seminary Lane. The new information sources, which were produced by the Pentecostal Initiative discussed herein, were the result of an ongoing dialogue and cooperation between university administrators, scholars, and community members. For the purposes of this paper, the term community engagement is defined as “the collaboration between institutions of higher education and their larger communities (local, regional/state, national, global) for the mutually beneficial exchange of knowledge and resources in a context of partnership and reciprocity” (Carnegie Classification, 2020, p.1). Since 1981, the University of Florida’s Division of Sponsored Research (DSR) has supported grassroots research for the exploration and development of learning tools for students, scholars, church leaders, and laypeople who study Black Church history. By highlighting the process of building ties to the local Black communities and the eventual resulting scholarship in the area of Black Pentecostal church history and culture, this study may point the way toward a more inclusive approach to religious research in the United States and around the world.

UF Division of Sponsored Research: Pentecostal Initiative

In 1980, a building construction student came to the reference desk at UF’s Library West asking for information on Rev. Charles Harrison Mason (1864-1961), the founder of the Church of God in Christ (COGIC) in Memphis, Tennessee. This male UF student, Mr. Lee, was studying to be a minister in the COGIC under Reverend Dr. D.R. Williams, pastor of Williams Temple COGIC, located on Seventh Avenue, in the Seminary Lane community. Lee was completing his studies at UF.

A search of available religious, non-religious, and African American reference sources did not produce any results. Reference librarian Sherry DuPree asked him to allow a few days for the return of a query from academic and public libraries for a biography or other information on COGIC. These searches did not yield any new sources. A query was also sent to the UF interlibrary loan desk to African American librarian, Marva Coward. In two weeks, DuPree received a pamphlet from the church headquarters with a telephone number that DuPree called to speak with the assistant. The next week, she received an envelope with several items which were given to the student. Lee took the items to his COGIC class. Next, DuPree received a telephone call from Williams, thanking the UF library for help. He shared the documents with his class and invited DuPree and family to visit his church.

The problem in researching early African American church leaders of the African American Holiness Pentecostal Movement, such as Mason, is that scholars found sources were not available, especially sermons. The primary and secondary sources often contain claims that were difficult to substantiate, since they were usually republished stories with little or no research to clarify claims. (DuPree, 1990, p.3).

In the process of aiding this information-seeking student, DuPree realized that a lacuna in African American religion research needed to be filled. Therefore, DuPree spoke to Dr. William Simmons, Director of the Institute of Black Culture (IBC) about establishing a Pentecostal research project. Although the history and culture of Baptist and Methodist African American churches have been documented, information about Holiness Pentecostal churches was omitted in academic literature due to the fact that they have been considered a subculture. In order to rectify this omission, Simmons, a Methodist minister, agreed to bring awareness to this specific area of religious culture. Simmons and DuPree spoke to Dr. James Scott and Dr. Art Sandeen of the Division of Student Services (DSS), about conducting and engaging UF in this research. Scott put Simmons and DuPree in contact with Vice President Donald Price in the Division of Sponsored Research (DSR). A meeting was held with Dr. Samuel S. Hill, Professor of Religion and Social Ethics (RSE). As a result of these interactions, DuPree wrote a proposal for a research study, with an emphasis on COGIC and founding of the African American Pentecostal Movement in the United States. The proposed study resulted in providing a reference book that included the locations of items from other academic institutions. UF administrators approved the research study and encouraged IBC to include the African American Studies Program and the Eastside African American communities in Gainesville.

A pilot study with a DSR grant of $500 included funding to carry out a survey. From that survey, DuPree and Simmons learned they needed to communicate with church historians, such as Dr. Ithiel Clemmons, the COGIC historian in Greensboro, North Carolina. In addition, the pastor of Mount Carmel Baptist Church in Gainesville, Rev. Dr. T.A. Wright, directed the project to Howard University Divinity School Director, Dr. N. Jones, and Dr. James S. Tinney, of Howard’s journalism department, for their far-reaching contacts and support communities. The initial report convinced those involved at DSR to continue the African American Pentecostal research. Several grants were written, and funds were received from the Howard University School of Divinity, the National Humanities Council, International Business Machine Corporation (IBM), the National Council of Churches, the Southern Regional Education Board, and the Lilly Foundation. Each grantor provided funds of between $1,000 to $15,000, which were used for recording equipment, travel, and archival supplies. Additional funding from the UF Gatorade Trust were used to hire and pay data entry clerks to enter items on spreadsheets. UF African American students were hired part-time, and tasked with the responsibilities to send letters, return phone calls, acquire items, and conduct other office duties under the supervision of Ms. Alma Johnson Small, the IBC administrative assistant.

Many oral interviews of family members in Pentecostal churches were conducted by DuPree and other African American researchers. A Pentecostal clearinghouse of materials was formed with scholars contributing and requesting information from all over the world, including Canada and London, England.

DuPree asked the National Archives and Records Administration in Washington, DC to detail the existing scholarship, in order to provide a historical overview of the African American Pentecostal movement that would provide sources for scholars. That question was the genesis of what became the Holiness-Pentecostal Movement Initiative, out of which came a network of supporters. Several major project goals were agreed upon by project stakeholders. The goal of the project was to promote gathering documentation from Black organizations, religious institutions, and individuals. Secondly, the project joined other academic institutions in encouraging scholarship on Pentecostalism. Third, the project explored both primary and secondary resources in academic settings and in the possession of individuals. Fourth, the project examined the academic perspective of students and scholars, who would use the information to produce theses and dissertations. This was in keeping with the realization that Holiness Pentecostals are a diverse group. Finally, organizers were committed to the idea of making this collection accessible to the general public. (DuPree, 1988, p.10-12).

As the existence of this project became known, many more African American Pentecostal organizations donated documents. In 1996, African-American Holiness-Pentecostal Movement: An Annotated Bibliography was published by Garland Publishing, for which Hill at RSE wrote a two-page preface. He mentions that one of the major repositories for the Pentecostal movement in the American Black Church was the Federal Bureau of Investigations. “A trip to the nation’s capital to see FBI reports belongs on your research trip itinerary” (DuPree, 2013, p.vii).

The Pentecostal Initiative produced A Biographical Dictionary of African-American Holiness-Pentecostals 1880-1990, printed in Washington, DC by the Middle Atlantic Regional Press, 1989. In the foreword written by Simmons at IBC, he observed,

It is surprising to learn that Pentecostalism in America began with an African American preacher in Los Angeles, California. From this publication, Pentecostals, as well as other Black Denominations, will gain pride in the knowledge that the Black church was in the forefront of a multi-ethnic religious movement in America. This dictionary should stimulate research and encourage our youth to gain a greater appreciation for the many contributions of Blacks in America (DuPree, 1989, p.vii).

After years of data collection and archival research, the question raised by a UF engineering student about the founding of the Black Pentecostal church can be answered, thanks to the cooperative effort known as the Pentecostal initiative. It all started with Rev. C.H. Mason.

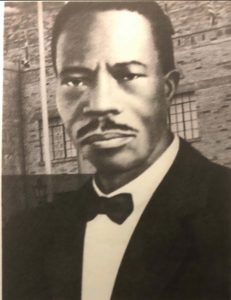

Rev. Charles Harrison Mason, Founder of COGIC

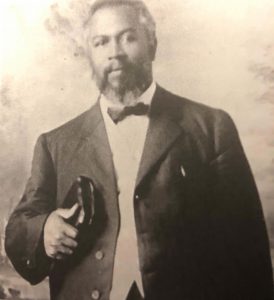

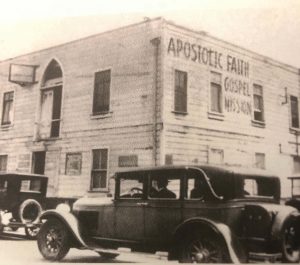

Mason (Figure 6.3.1) was raised in a rural area, near Pine Bluff, Arkansas to a family of ex-slaves. Mason was not allowed to have a formal education; he worked on farms. Yet, Mason learned to read, write, and understand the Bible (Stewart et al., 2017, p.42). Mason was raised in the Baptist Church and involved in the Sanctified Holiness Movement with Rev. Charles Price Jones (who died in 1949) in Los Angeles, California. Mason heard about the baptism of the Holy Ghost and he along with Rev. D.J. Young and Rev. J. Jeter traveled from Mississippi to Los Angeles, California, to learn and receive this New Testament blessing. Mason received his baptism in the Holy Ghost at the famous Azusa Street Mission Revival, under leader Rev. William Joseph Seymour (1870-1922) in March 1907 (Stewart et al., 2017, pp.22-24).

The Azusa Street, Apostolic Faith Gospel Mission, Revival signaled a new approach to religion, and a new oral tradition of speaking in tongues or glossolalia. Historian and President of the William Seymour College and Educational Foundation, Estrelda Y. Alexander, stated Seymour changed his approach to worship to a personal relationship with Jesus Christ, using scripture from Acts 2:4 (Alexander, 2011, pp.124-125).

After Mason returned from Los Angeles to Mississippi, he was disfellowshipped (similar to being shunned) by Jones and others. Mason and his followers changed COGIC from Holiness (living a clean life, set apart from worldly processions) to Pentecostal. Until 1916, Mason had integrated congregations in COGIC, but after the film Birth of A Nation, which opened in 1915, societal racism caused COGIC to become a predominantly Black Church (Stewart, et al., 2017, p.42). At COGIC churches, members were baptized in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost, known as the Holy Trinity. Baptism in the Holy Ghost is the evidence of speaking in unknown tongues. Pentecostals believe they should share, love and be led in brotherhood with all men and women from all cultures (Faulkner & Smith, 2017, pp.58-60).

Because few early Pentecostal church records were saved, one of the most important government sources on Mason and others in Black church history have been Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) reports, which were written (often daily) surveillance notes that are accepted by scholars as factual. It is through the FBI primary documents from 1917 about Pentecostal leader Mason that scholars have been able to verify he was opposed to COGIC participating in World War I (DuPree, 2013, p.412). Aided by increased access to archival documents, research continues to bring to light a more nuanced understanding of the founding of African American Pentecostalism and the context from which it sprung.

Community Engagement Outcomes

UF students and senior leadership have periodically forged bonds with Black community organizations which may not be directly connected to the Pentecostal Initiative. For instance, campus members took part in a broader coalition to encourage Gainesville City Commissioners and others to consider saving the remainder of the Black Historic neighborhood, Seminary Lane, an area close to UF’s campus. UF African American leaders, faculty and students have connected with this neighborhood to save Gainesville’s oldest underserved Eastside community. Furthermore, UF scholars created a UF African American studies community syllabus and shared it with African American community network leaders. Other UF affiliated groups have identified immediate COVID-19 pandemic educational needs, such as after-school tutoring to support secondary students in these challenging times.

Although UF and local African American communities have co-existed for decades in the adjacent neighborhoods, the Seminary Lane community housing issues have been problematic. Gentrification has caused Black families to lose their homes vis-à-vis higher-priced housing developments geared to college students (DuPree, 2020).

In the era of the Global Pandemic, the UF Gator Jewish Student Center (GJSC), located near Seminary Lane on 5th Avenue, has played a part in strengthening UF’s ties with Black neighborhoods by helping to distribute governmentally funded face masks, in a collaboration with the African American community churches and civic organizations. The cloth masks were washable and were a great help to families in the Seminary Lane community and other Eastside African American communities.

UF GJSC leaders collaborated with African American church leaders. An agreement was reached between organizations to distribute protective face masks. African American churches sent members to the UF GJSC to pick up masks for transport to Black churches for broader, free distribution to adults as well as school children. On the day of the mask giveaway, African American church members directed long lines of traffic to African American church parking lots, as drivers rolled down their car windows to receive packages of masks. This was a team effort to distribute and to help maintain healthy habits by wearing a mask and keeping a social distance.

Now, as citizens and students walk down the street in Gainesville they wave and smile at each other and talk with their masks on. The communication has supported better understanding of each other’s culture. African American and Jewish religious leaders made Gainesville a better and healthier place for all residents.

The UF African American Studies Program presented a proposal for educational opportunities where UF students communicated and earn class credit with various church and community organizations. Gainesville City Commissioners formed a partnership with UF to discuss housing problems related to gentrification. They also worked together to ameliorate inadequate housing conditions in Black neighborhoods. Thus, a long-term African American community housing need has been identified and acknowledged.

Religious Engagement Outcomes

Increased use of African American Holiness Pentecostal resources has influenced the evolution of academic research and community engagement during the last four decades. Reference sources have been available online and in print to enhance the study of the Pentecostal movement, which has been the fastest growing religious group (Banks, 1993).