7 Reflections on the African American Studies Program by Harry B. Shaw

Abstract: This chapter is a reflection on the development of African American Studies at UF by Dr. Harry B. Shaw, the first African American Associate Dean of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences (formerly University College) on two levels: (1) professional and (2) personal. The chapter includes observations by Dr. Shaw about his direct involvement in the development of the African American Studies Program at the University of Florida. Dr. Shaw arrived at UF in 1973 as a faculty member in the Department of English and was engaged in the historical development of the Program, even after his retirement as Emeritus Professor in 2004.

Reflections on the African American Studies Program

My reflections on the history of the African American Studies Program at the University of Florida are both professional and personal and consist of chronicling and examining my observations of and direct involvement in the Program and its development from its beginning in 1970 through its 50th Anniversary in 2020. This examination considers the overall effects of a number of factors that include the Program’s historical context, administrative and academic setting, and leadership through its trials, opportunities, accomplishments, and shortcomings.

More specifically, my views and judgements reflect my observations of the academic development of the African American Studies Program at the University of Florida in 1969 and the hiring of Dr. Ronald C. Foreman as the first Director of the African American Studies Program in 1970; the national, local, and University of Florida sociopolitical context of the early stages of the Program; along with my own professional connections with the University of Florida as a faculty member in the English Department and as an administrator in the University College and the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. In addition, I will address the failure of the Program to attain departmental status during the 30 years of Dr. Foreman’s leadership of African American Studies. I will also offer commentary on the strengths and weaknesses of the African American Studies Program; observations and reflections of the attitudes of the Black community toward the African American Studies Program and the University of Florida; and reflections on my professional life at the University of Florida, including lessons for today’s advocates of African American Studies.

While the history of the African American Studies Program at the University of Florida may not be readily known even to those within the institution, reflection on its inception and development sheds important light on the histories and cultures of the University of Florida, the local community of Gainesville and surrounding area, the state of Florida, and the nation. The African American Studies Program was established in 1969. The first director was Dr. Ronald Foreman, and the Program enrolled its first students in 1970. It is also noteworthy that during the next year, 1971, when there were only three Black professors, one Black administrator, and 387 Black students at the University of Florida, the African American Studies Program awarded its first certificate. Key figures in the establishment of the African American Studies Program at UF included administrators Dr. Manning J. Dauer, Chairman, Social Sciences Division; Dr. Harry H. Sisler, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences; and Dr. Harold Stahmer, Associate Dean, College of Arts and Sciences. The faculty who assisted in the earliest development of the Program included Dr. Hunt Davis, Jr., (History); Dr. Seldon Henry, (History), Dr. Steve Conroy, (Social Sciences), Dr. James Morrison (Political Science); and Dr. Augustus M. Burns (Social Sciences, History). A number of students played important roles in the Program’s beginning, including Samuel Taylor (the President of Black Student Union in 1970 and the First Black Student Government President in 1972); David Horne, a Doctoral candidate in History; and Emerson Thompson and Larry Jordon, undergraduate students (UF Liberal Arts and Sciences, 2020). Going beyond these essential facts, however, to reflect on the impetus and the circumstances that gave rise to the Program is equally telling because doing so allows these facts to be seen in proper perspective.

Like so many Black people at this time, emerging from the turbulent decade of the 1960s, I took personally every chapter, every page, and every sentence of the long history of brutality being played out across the nation against African Americans. I followed closely as this violence spurred an increase in organized Black resistance, particularly that beginning in 1960 with the lunch counter sit-ins in Greensboro, North Carolina. The 1960s were a continuous cycle of brutal racial repression followed by protest in the form of sit-ins, marches, and boycotts, or eruptions into violent riots in major cities, including New York, Newark, Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, and Watts, Los Angeles. It is important to note that in too many instances, the authorities in the nation reacted to Black resistance against oppression by escalating violence against Blacks. The violence was perpetrated by a combination of racist vigilantes, organized mobs, police agencies, or—too often—even federal government entities, particularly the FBI.

The Civil Rights Movement and its rootedness in Black history and the violent response to it forms the historical backdrop to the demands by students for African American Studies departments in the 1960s. The decade was punctuated by a gruesome string of assassinated Black leaders, their sympathizers, and innocent Black citizens—some of the murders committed in prime-time, some in the middle of the night. In 1963 it was Medgar Evers, head of the Mississippi NAACP; four young Black girls, Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley, Carole Robertson, and Carol Denise McNair in the Birmingham 16th Street Baptist Church bombing; and John F. Kennedy, president of the United States. In 1964 it was three young civil rights workers, James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner, in Philadelphia, Mississippi. In 1965 it was Malcolm X, leading figure in the Nation of Islam. In 1968 it was Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert Kennedy, Attorney General of the United States. In 1969 it was Black Panthers Fred Hampton and Mark Clark in Chicago. While clearly the African American Studies Program at the University of Florida grew most immediately out of the unrest caused by the death of Dr. Martin Luther King in 1968, it also had its roots in the culmination of the turbulent, violent decade of the 1960s that prompted positive responses from the University of Florida and other institutions of higher education.

While this bloody and brave decade set the stage for the African American Studies Program at the University of Florida and ushered in a more ameliorative approach by some colleges and universities, the changes came with noticeable imperfections and with many schools reacting largely to the prod of federal court orders to desegregate. Still, institutions of higher education offered some of the nation’s brightest rays of hope. In this setting of struggle—including walkouts and demands primarily by Black students for the African American Studies Program and the Institute of Black Culture—the Program began. The interactive dynamic that played out among violence, protest, and progress called to mind teachings of the great Frederick Douglass who said, “Power concedes nothing without a demand” and “If there is no struggle, there is no progress.” Any progress made by African Americans at the University of Florida stemmed from a struggle against competing entities and often recalcitrant mindsets. From my vantage point of being in the Dean’s Office, I was privileged to witness and be a part of the struggle.

Succinctly, that is the background—the setting—for the establishment of the African American Studies Program at the University of Florida, and my view of it. As I recall some of my own career experiences during the very early years of the African American Studies Program, I provide hints of what the general atmosphere was like locally on the ground.

It is worth mentioning that although I did not become part of the University of Florida African American Studies Program until 1973, three years after it began, I had some awareness of, connection to, and affinity with the Program since its inception. This insight was afforded by my prior colleagueship from 1968 to 1970 at Illinois State University with the Program’s first director, Dr. Ronald Foreman. Together there we experienced some of the vicissitudes of African American professional life in higher education during the 1960s and 1970s. When he left Illinois State University in 1970 to become the Director of the African American Studies Program at the University of Florida, he kept me apprised of the early development of the Program.

As to the local atmosphere, it should first of all be remembered that in 1970 the University of Florida was one of those institutions under a federal court order to desegregate. Therefore, it seemed clear to me that simply because Black students were able to enroll at the University of Florida, to have an Institute of Black Culture, and to begin an African American Studies Program did not mean that suddenly and completely the whole University was converted like Paul on the road to Damascus. Rather, in my experience and observation, what moved things forward was a combination of progressive leadership at various levels of the University and the dogged determination of persons who were involved with the African American Studies Program per se, as well as those Black faculty members who were collectively involved in trying to safeguard the well-being and progress of Black faculty staff and students at the University of Florida. Notable in this effort were Dr. Jacqueline Hart, the Affirmative Action Coordinator, Dr. Roderick McDavis from the College of Education, Law Professor Michael Moorhead, Dr. Carlton Davis from the Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, Drs. Ronald and Grace Henderson from Sociology, and myself. We were some of a group who spent many hours during and after our workdays pooling our strategies to help keep things on a favorable trajectory. We had no choice but to be persistent. Although success was not always guaranteed, giving up was not an option.

The appreciation of the Black community for the efforts and products of the African American Studies Program was largely affected by their prior familiarity with and opportunities for exposure to elements of African American history and culture, often made available by the African American Studies Program. Speakers, artists, and classes were generally well received by Black gown but—not surprisingly—less well attended by Black town.

It should be kept in mind that, in those days, there really were not very many Black students on campus and only a handful of Black faculty. The University of Florida, under a federal court order to desegregate, faced two big problems: the need to hire more Black faculty members and the need to enroll more Black students. Building an African American Studies Program without either of these critical masses would be especially difficult. As a newly appointed assistant Dean in University College, and as a friend of the Director of the Program, I felt a responsibility and looked for opportunities to help.

In the early 1970s there was no College of Liberal Arts and Sciences—it was created in 1978. Before then, there were the College of Arts and Sciences and the University College. University College was the lower division college which was primarily responsible for providing general education for the University of Florida. Arts and Sciences was an upper division college which provided courses leading to various majors. In 1978 the two colleges merged to form the present-day College of Liberal Arts and Sciences (CLAS). The new college moved into the newly constructed General Purpose A building (GPA), later named Turlington Hall.

It is unlikely that the following part of my reflections is recorded in any written history, but by way of providing context and atmosphere, I can reveal that my own situation in University College at first seemed tenuous at best. In 1973, during my interview process for the assistant deanship position in University College, the few Black faculty members who met with me told me that my immediate predecessor, a Black Assistant Dean, had been physically thrown out of his office by the college dean, Robert “Bob” Burton Brown. One of my new colleagues even estimated that I would last as little as two weeks in the job. The full story is very long, but the important thing is that I somehow exceeded this prediction by more than three decades in the college office, serving with four different deans.

It turns out that I was able to help the African American Studies Program in a fundamental way. Although my beginnings seemed tenuous based on the reputation of my very headstrong, irascible dean and his determination to live up to it, as far as I could tell, he treated me fairly. When I went to the first University College Assembly where I was introduced to department chairs and faculty, I was astonished to see only other one Black faculty member. In the following weeks, I carefully but persistently expressed concern about the numbers of Black faculty. One day, the dean came into my office and told me that we needed to hire more Black faculty and that he was putting me in charge. Although I was surprised at this abrupt turn, I did not dare drop the ball.

I was able to convince Dean Brown and Vice President Robert Bryan to try a different approach to hiring Black faculty. Since pursuing Black superstar faculty had been largely unsuccessful because it seemed they were invariably more interested in elite universities like Harvard, Princeton, and Berkeley than they were in the University of Florida, I suggested pursuing promising Black ABDs—that is, doctoral candidates who had completed all but the dissertation.

Working with Dr. Jaquelyn Hart, Affirmative Action Coordinator, we set up what we called the Vita Bank. I sent out letters to Black ABDs across the country requesting vitas. Then I sent letters to all University of Florida departments informing them of the project and asking whether they had vacancies. Altogether in the first year of serious recruitment in 1974, primarily through this process, we hired 14 new Black faculty members in various departments.

One of the Black faculty recruits that I am most proud of is Dr. Mildred Hill-Lubin. In addition to sending her the usual letter, in 1974 I traveled to the University of Illinois to personally invite her to the University of Florida. I mention her not only because she became a lifelong dear friend and colleague in the English Department, but because she became such an important addition to the early African American Studies Program at the University of Florida.

The central administration was so pleased with our success that it turned the green light to red. As a result, very few Black faculty members were hired in 1975 and 1976. In 1977, the green light turned on again and the Vita Bank rolled into action, resulting in an unprecedented 20 Black faculty hires. Once again, the English Department, the African American Studies Program, and the University of Florida considered themselves very fortunate to have landed a star, Jim Haskins, among this group of recruits. Jim Haskins, as a scholar, writer, and professor, added immensely to the overall stock of the African American Studies Program in terms of prestige, attractiveness, and leadership.

Through logic that seemed short-sighted, the University turned the red light on again. Some of these hired Black faculty members remained at the University of Florida for years and the departments were made richer by their added professional resources. However, whenever University of Florida Black faculty left—either perishing for not publishing or excelling here and moving on to something bigger and better—some considered such loss a failure and criticized the system that had been called so successful. The unrealistic expectation was that once Black faculty had gotten into these hallowed halls, they would be content to stay here forever. The reality is that some Black faculty, like astute academics in general, used the University of Florida as a career steppingstone. I think the average time of employment for faculty in general at that time was about four years. Despite our efforts to proceed full speed ahead, the University of Florida continued to play “red light-green light” in hiring Black faculty for a number of years. But purely in terms of numbers and quality of Black faculty, the University of Florida was beginning to compare favorably to prestigious universities around the country.

One lesson here is that the successful recruiting and hiring of Black faculty has to be not only a concerted effort but a continual process. Another sobering lesson is that the University’s central administration was much more easily pleased than we were.

Of course, many of us, remembering the early demands of Black students for Black Studies, were hoping that the increase in the number of Black faculty would positively impact the number of Black students on campus and vice versa. Therefore, simultaneously there was a similar effort to recruit and retain significant numbers of Black students whose presence would be of paramount importance to the prospects of a fledgling African American Studies Program and for whom the African American Studies Program was an attraction.

Because it was difficult and expensive to compete with more prestigious universities offering more attractive scholarships to recruit the top Black students, special efforts were made to locate average students. The bulk of Black students attending the University of Florida in the early years from 1969 through the 1970s were specially admitted. In fact, it was not until the year 1985 that the number of regularly admitted Black students was greater than the number of specially admitted Black students. But from these we had many high achievers, including student body presidents, dean’s list honorees, and honor roll students, showing it is more important what one does with an opportunity than where one begins.

Enrolling specially admitted students meant also providing special programs to assure their retention and success. As Assistant Dean of University College, part of my responsibility was to supervise the directors of several minority programs. Two of these minority programs were federally funded: the Student Support Services Program, a special-admission minority program, and the Upward Bound Program, a minority high-school-to-college bridge program. I also wrote successful proposals for two additional minority programs funded by the University of Florida, the Student Enrichment Services Program (SESP) and the Academic Enrichment and Retention Services (AERS).

Moreover, Mr. John Boatwright, Director of Minority Admissions, and others continued to recruit and support regularly admitted Black students through a growing scholarship program, especially the National Achievement Scholarship Program.

The argument for continuing special efforts to attract and to retain Black students often met with opposition. For example, Vice President Robert Bryan called me into his office one day around 1979-80 and told me that schools in Florida had been integrated for 12 years. As a result, he pointed out, Black children and white children had been in school together and were exposed throughout to the same educational opportunities, therefore clearly there was no more need for any special programs for Black students at the University of Florida. Furthermore, he declared he intended to dismantle them all. Although that dismantling did not happen, the battle to preserve the programs against mindsets misguided by such logic and misinformation set the tone for the ongoing struggle for improving—and at times even defending the very existence of—programs to assist Black students (Lempel, 2018). In this atmosphere, the University’s Black community had to find ways to work with its champions and circumvent its detractors to move forward.

Before 1990, the term “minority” was virtually synonymous with Black or African American. With the arrival of President John Lombardi and his provost, Andrew Sorensen, the—perhaps well-meaning—emphasis on an egalitarian approach to all minorities presented another challenge. Dr. Lombardi served as president of the University of Florida from 1990 to 1999. “Parity among minorities” was the motto of their approach to diversity efforts.

The good news is that minority student enrollment increased significantly.The bad news is that—ironically—Black enrollment first abruptly leveled off and then actually declined during this time.

The reasons were obvious to some of us. In the state of Florida, the academic profiles of admissible Hispanic students were only slightly below that of whites and the academic profiles of admissible Asian students was slightly above that of whites, but the academic profiles of African American students were considerably below the others for historic reasons. Once pitted against the children of wealthy Cuban refugees and the highly selected, talented Asian students, Black students—though capable of doing well—found increasing difficulty competing for scholarships or even being admitted. The lesson here is that friendly fire can obviously be just as harmful as enemy fire.

In 1999, there was a changing of the guard. Dr. Lombardi left the University of Florida and Jeb Bush became governor of Florida. Governor Bush promoted a “race-blind” approach sanctimoniously called “One Florida” striking down Affirmative Action in the Sunshine State (Tucker, 2016). After seven years of Jeb Bush, Black student enrollment did not keep pace with overall growth of other minorities. While in 1999 Black students comprised 14.4% of the student body, their numbers and percentages of the student body began and continued to decline significantly (University of Florida Common Data Set 2006-2007). More recent figures show that percentages of other minorities continued to rise, but African Americans’ enrollment percentages declined even further to below 10 to 5.97 percent of the student body in 2017, and African Americans have become the only minority group at the University of Florida that enrolled less than its percentage in the general population (Data USA: University of Florida, 2017).

The African American community applauds the University of Florida for valuing diversity and it continues to encourage and support a more equitable representation within the diversity.Since the need and the justification are just as great as they have everbeen, hopefully with an abundance of goodwill and genuine desire for the best, the State of Florida and the University of Florida together will earnestly work to discover ways to achieve equitable enrollment of African American students. My observation is that if these efforts fail, it may lead to a bitterly ironic outcome that a diminishing number of Black students will benefit from the success of the African American Studies Program—which owes its very existence to the struggles and demands of African American students in the first place.

Although the solution to the problem of declining Black enrollment has yet to be addressed successfully, this major advancement of African American Studies toward departmental status has paralleled and grown out of the sustained efforts over many years by Dr. Foreman and all the Program directors who followed him to realize their visions of acquiring the key elements of adequate and suitable office space, enough autonomous faculty lines, and a viable interdisciplinary core curriculum. One measurement of the progress made by the Program is to look at the conditions of these elements early on and through the years.

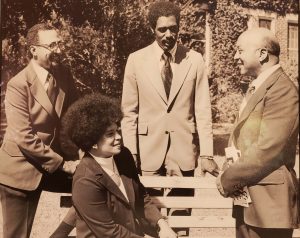

When I came to the University in 1973, the one-room office for African American Studies was located on the 4th floor of Little Hall, and it was by no means a penthouse. Throughout the time that Dr. Foreman and I were at the University of Florida, our offices were usually in the same buildings or in close proximity. We moved from Little Hall to Turlington Hall, back to Little Hall again, and then to Walker Hall. We were moving forward and—for the most part—upward. Figure 7.1 shows some of the first African American faculty members at UF including Dr. Foreman, Dr. Mildred Hill-Lubin, Dr. Richard Barksdale, and myself.

Dr. Ronald C. Foreman, Jr. received his Ph.D. in Mass Communications from the University of Illinois. He taught at Shaw University, Knoxville College, Tuskegee Institute, and Illinois State University before joining the University of Florida in 1970 as the Director of the Afro-American Studies Program and faculty member in the English Department. For 30 years he directed Afro-American Studies, teaching the Program’s core courses as well as a variety of literature courses in the English Department.

Among other duties, he served for many years as faculty advisor for the Black Graduate Student Organization and as a member of the Board of Directors of the Florida Folklife Association. In 1970, along with Dr. Carlton G. Davis of the Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences and Dr. Elwyn Adams of the Music Department, Dr. Foreman was one of the first three tenure-track African American faculty members hired at the University of Florida. He and other faculty and students were instrumental in laying the groundwork for many of the policies and programs that today foster diversity and promote humane enlightenment at the University.

One of Dr. Foreman’s immediate concerns and another measure of moving forward was the curriculum of the African American Studies Program. The curriculum in those early years consisted of one or two introductory courses in African American Studies and an upper division or senior seminar-level course. These were taught by Dr. Foreman. As I remember, one or two other courses might be taught by faculty members in the History Department. The goal of the Program was to have students complete enough credit hours to earn a certificate in African American Studies. Indeed, awarding certificates was supposed to be a way for the Program to justify itself.

There were immediately several challenges to achieving this goal. First of all, the limited number of courses that counted for African American Studies made them easy to overlook among the wide array of course offerings campus-wide. Additionally, at that time, especially among the general student body, the lack of familiarity with and interest in a non-traditional subject like African American Studies combined with the very small number of African American students on campus meant that there were relatively few certificates awarded.

Clearly being able to offer core courses of the African American Studies Program that also provided credit toward fulfilling the general education requirement would help build interest in the Program’s introductory level courses. However, without a core junior and senior faculty to meet students’ needs by providing courses that fulfill general education and certificate requirements, the certificate program enrollment continued to be low as students worked to meet their other graduation and major requirements.

In 1974, as Assistant Dean in University College, which was the college that provided the university’s general education, to complement my efforts to increase the numbers of African American faculty and students, I saw another way to help the African American Studies Program while pursuing my own interests. I created the first African American literature course in the University College English Department. I was able to have the course offered for general education credit, helping to boost the number of students who earned certificates in the African American Studies Program.

It is accurate to say that Dr. Foreman could be conveniently relied upon to be businesslike and diplomatic when making the case for the needs of the Program, as indicated by his early vision and hopes for enlargement of the Program’s library acquisitions and curriculum with a budget sufficient for expanding its core teaching staff to at least six faculty positions.

While Dr. Foreman had the requisite vision to assemble all the necessary parts of the Program to lead a department, during his tenure, he was never able to see the University leaders at various levels sufficiently aligned to accomplish the transition or even move meaningfully toward a minor or major. Mindsets either at the vice president’s level or the president’s level too often did not see the African American Studies Program as central to the mission of the University of Florida. Furthermore, other competing programs also vied for valuable and scarce resources, which had to be husbanded carefully under the watchful eye of the Board of Regents of the State of Florida. I also reflect on the hard fact that the State of Florida during this time was still a Deep South state. Occasionally, I was reminded of this whenever I encountered visual vestiges of the once-pervasive system of racial discrimination. At that time, I could still see the rare residual “Colored” and “White” signs on bathroom doors at filling stations and—more alarmingly—even at the University of Florida’s Shands Hospital. At that time also, very often Dr. Foreman was concerned with fighting for adequate funding to operate the Program, seeking funds for faculty lines, events, speakers, secretarial support, equipment, supplies, etc. In this context, I am reminded of John Milton’s cogent line, “They also serve who only stand and wait.”

In this context, when one wonders about why Dr. Foreman was not successful in achieving departmental status during his 30 years as the director of the African American Studies Program, one should remember that success is sometimes just holding on and not losing ground. While African American Studies programs at some universities achieved departmental status early on, some have never achieved it, even at prestigious schools. At some universities, support for Black or African American Studies programs has been discontinued, or they have become subsets within other academic units such as history departments. At universities across the country African American Studies programs waxed and waned; some flourished and some declined, depending on leadership and on the political/economic environment. The factors that dictated lack of success for Dr. Foreman to achieve departmental status for the African American Studies Program remained operant until very recently, when, under the leadership of Dr. Sharon Austin, the stars and various levels of administration were aligned favorably for the upward transition to begin.

The African American Studies Program directors who followed Dr. Foreman brought credentials and experience from around the country and echoed and extended his vision. Upon Dr. Foreman’s retirement in 2000, Dr. Darryl M. Scott with a Ph.D. in History from Stanford University served as director of the African American Studies Program until 2003. He emphasized the need to attract a diverse faculty with broad interests in the social sciences and the humanities in order to develop a strong major and a well-rounded graduate program.

From 2003 to 2004, Dr. Marilyn M. Thomas-Houston with a Ph.D. in Cultural Anthropology from New York University served as the next director of the African American Studies Program and continued the theme of developing a strong African American Studies Program, stressing the interdisciplinary and holistic foundation of studying the Black experience. Her main goals were to build an undergraduate program that conferred both a Bachelor’s degree and a graduate certificate, establish a strong research component that included internationalization, develop strong community relations through a service-learning component and community outreach initiative, and hire dynamic and productive faculty and administrative staff. She stressed the importance of acquiring outside funding to develop various resources, such as graduate assistantships and post-doctoral fellowships, faculty exchange programs with HBCUs, study-abroad programs that trace the African American Diaspora, and community history projects and exhibitions. Dr. Thomas-Houston’s imaginative approach supported her goals and enriched the African American Studies Program with innovations like the annual Ronald C. Foreman Lecture Series, which features lectures by Black Studies scholars, and the Harry B. Shaw Undergraduate Travel Grant, which sponsors selected undergraduate students to attend and present their research papers at professional conferences.

When I retired from the University of Florida in 2004, Dr. Terry Mills replaced me as Associate Dean for Minority Affairs in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. From 2004 to 2006, Dr. Mills, with a Ph.D. in Sociology from the University of Southern California, served also as the Interim Director of the African American Studies Program. A major accomplishment of his was transitioning the curriculum from consisting largely of “special topics” courses to revising and receiving approval by the University Curriculum Committee for five courses that became general education courses and/or Gordon Rule courses and fulfilled the State of Florida’s writing requirement. The impetus gained from getting these courses approved in turn set the groundwork for his second major accomplishment of the development of an 18-credit minor in African American Studies that was approved by the Curriculum Committee.

From 2006 to 2010, Dr. Faye Harrison with a Ph.D. in Anthropology from Stanford University served as director of the African American Studies Program and continued to strengthen the Program’s minor and to lay the groundwork for the Program’s major by adding to the number of courses eligible for general education and Gordon Rule credit and significantly growing the number of students taking African American Studies Program courses and receiving minors.

From 2010 to 2011, Dr. Stephanie Evans with a Ph.D. in African American Studies from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, served as director of the African American Studies Program and continued to add to the number of students enrolling in African American Studies Program courses, maintaining the momentum of the Program’s minor and continuing en route toward the major.

From 2011 to 2019, Dr. Sharon Austin with a Ph.D. in Political Science from the University of Tennessee served as director of the African American Studies Program. She continued the progress of the Program’s directors before her, and under her helm in 2013, the Program began offering the major and awarded the first BA degrees in 2014. Under her leadership, the Program enjoyed popularity, becoming one of the fastest growing majors at the University of Florida. Most notably, with the aligned support and cooperation of Dr. David Richardson, Dean of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, Dr. Joseph Glover, Provost of the University of Florida, and Dr. Kent Fuchs, President of the University of Florida, she was able to lead the final successful effort to achieve approval to develop the long-sought departmental status for African American Studies.

To facilitate this effort, the African American Studies Steering Committee was established late in 2017 to review the status and make recommendations about the future of the African American Studies Program. The Committee consisted of Dr. Jacob U. Gordon, Professor Emeritus, University of Kansas; Dr. Bonnie Moradi, University of Florida Psychology Department; Ms. Stephanie Birch, African American Studies Librarian, University of Florida Library; Dr. Vincent Adejuma, Lecturer, African American Studies Program; and Dr. Mary Watt, Associate Dean, College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. A final report of the Committee included a strong recommendation for a departmental structure, a new director, faculty, resources, and a strategic plan. On April 23, 2018, African American Studies Program stakeholders (faculty, affiliates, the Advisory Committee, and Associate Dean Watt) overwhelmingly voted to approve the African American Studies Steering Committee Final Report and Recommendations (UF Digital Collections, Institutional Repository).

In the fall of 2019, the dean of the college, Dean Richardson, accepted the Steering Committee’s Final Report and appointed Dr. James Essegbey as Interim Director of the African American Studies Program, pending a national search for a permanent director. Dr. Essegbey, with a Ph.D. in Linguistics from Leiden University in the Netherlands, has served from 2019 to 2020 as interim director of the Program. The dean also promised four new faculty tenure-track positions. Subsequently, Dr. David Canton, who was the Director of the Africana Studies Program at Connecticut College, was selected as the new Director of the African American Studies Program, effective August 2020. He is expected to lead the Program toward a departmental status.

While the approach of African American Studies will continue to be interdisciplinary, a recognized major advantage to the departmental status is greater autonomy to hire full-time tenured and tenure-track faculty in African American Studies without the reliance on faculty from joint appointments in other departments. Goals for the coming department include having a graduate program that offers Master’s and doctoral degrees in African American Studies as well as a Graduate Certificate in Race and Ethnicity. Fittingly, the African American Studies Program in 2019 moved its offices to adequate and suitable space in Turlington Hall.

Recently, I toured the new offices of the African American Studies Program on the first floor of Turlington Hall and can say truly that looking back at office space is one clear measure of the Program’s progress. Dr. Foreman would be pleased with the new offices. He would also be pleased to see the fulfillment of his vision of Program’s needs, including enlargement of the Program’s core teaching faculty, expanded library acquisitions, and broadened curriculum, supported by non-academic career staff.

Fortunately, today African American Studies does not have to be overly concerned with meeting quotas for granting students certificates; the Program is pursuing higher goals. When I look back to where the Program was and see how far it has progressed, I can very much appreciate the tireless talented leadership of the African American Studies Program—including contributions of the aforementioned past directors. Additionally, as applies more specifically to the present trajectory toward departmental status, these efforts could not have been successful without the vision, cooperation, and partnering of Dean Richardson, Provost Glover, and President Fuchs.

As the Program moves forward, there should never be the question about what one can do with a major in African American Studies. Literally the sky is the limit. Dr. Mae Jameson, the NASA astronaut, earned an African American Studies major from Stanford University and former First Lady Michelle Obama holds a minor in African American Studies from Princeton University. In fact, the dynamic, multicultural, multidisciplinary curriculum of African American Studies is the epitome of a liberal education—inclusive of topics often avoided by other curricula, yet vitally relevant in explaining and shaping the world around us.

Speaking of majors, according to the most recent former Program Director, Dr. Sharon Austin, the University of Florida’s African American Studies Program has among the largest number of majors in the country, considerably more than most African American Studies programs or departments at peer universities. This accomplishment speaks highly of the effectiveness and dedication of the directors and the faculty of the African American Studies Program, especially in light of the aforementioned serious enrollment challenges for African American students.

As the Program transitions into a department, it will reasonably anticipate hiring more faculty and recruiting and retaining more Black students at the University of Florida. By doing so, the new department will be fulfilling the stated mission of the University of Florida and thereby helping the University to legitimately put into effect its top tier classification. For all students and faculty at the University of Florida, for all Americans, and indeed for all the world, the kind of unveiling and sharing of the African American experience done by African American Studies scholars and teachers is altogether essential to any true and unredacted version and understanding of the American experience. For this reason, my great expectation for the African American Studies at the University of Florida is that it will indeed look back and move forward.

The light is green now, and the future should be bright.

Chapter 7 Study Questions

- What are some of the critical issues raised by the author about the status of Black Education at UF?

- How do you compare the author’s reflections in this chapter to any other one Black literary writer in African American Literature?

- To what extent are the author’s experiences similar to those experienced by Black faculty and administrators at other Historically White Colleges and Universities (HWCUs)?

References

African American Studies Steering Committee. (2018, April 24). Final Report & Recommendations. University of Florida. Retrieved March 29, 2021, from https://ufdc.ufl.edu/IR00010296/00001

Data USA. (2017). University of Florida: Enrollment by Race & Ethnicity. Retrieved March 29, 2021 from https://datausa.io/profile/university/university-of-florida#enrollment

Lempel. L. R., (2018). The Long Struggle for Quality Education for African Americans in East Florida. Journal of Florida Studies, 1(7), 16-25. Retrieved from http://www.journaloffloridastudies.org/files/vol0107/LEMPEL_Integration.pdf

Tucker, N. (2016, January 7). He got his way. Then he got a mess. The Washington Post. Retrieved March 29, 2021 from https://www.washingtonpost.com/sf/national/2016/01/07/decidersbush/

University of Florida: College Liberal Arts and Sciences. (2020). African American Studies History. Retrieved March 29, 2021 from https://afam.clas.ufl/history

University of Florida. (2007, April). Common Data Set 2006-2007, Enrollment and Persistence: Enrollment by Racial/Ethnic Category. [University data report]. Retrieved from https://ir.aa.ufl.edu/media/iraaufledu/common-data-set/cds2006-07.pdf