8 The Life and Times of Stephan P. Mickle (1944-2021): First UF African American Graduate and the College of Law Connection by Jacob U’Mofe Gordon

Abstract: The life and times of the first African American Senior District Judge of the United States District Court for the Northern District of Florida is presented in this chapter by Professor Emeritus Jacob U’Mofe Gordon, University of Kansas. Judge Stephan P. Mickle was the first African American to receive an undergraduate degree from the University of Florida (1965). He subsequently earned two UF degrees: a Master of Education 1966 and a Juris Doctor in Law in 1970. Judge Mickle received the University of Florida’s Distinguished Alumni Award in 1999. His wife, Evelyn Marie Moore Mickle, was the first African American to receive a Bachelor of Science in Nursing from the UF’s College of Nursing in 1967. These reflections conclude with remembrances from his colleagues, law clerks, faculty, and dean of the Levin College of Law at a special ceremony honoring Judge Mickle’s decades of service in the pursuit of equal justice.

Stephan P. Mickle was born on June 18, 1944 in New York City. He is one of four children by his parents, the late Mr. Andrew R. Mickle, from South Carolina, and his wife, Mrs. Catherine Berry Mickle. They both graduated from Bethune-Cookman College (now Bethune-Cookman University) in 1955 and 1957, respectively. They became successful educators in the Alachua County Public Schools. Perhaps Mr. Mickle’s major contribution to the City of Gainesville in Alachua County was his service as Director of Aquatics, where he taught swimming to generations of children in Gainesville. Stephan’s three siblings were Andrew (deceased), Darryl L. and Jeffrey A.

As educators, Stephan’s parents imbued the values of education, hard work, and fairness in their children. These values led them to success, notwithstanding racial barriers against African Americans, which were especially marked at that time. Andrew was a geologist; Darryl became a veterinarian in Atlanta; Jeffery is an educator in Ocala, Florida; and Stephan became the first African American graduate from the University of Florida and the first African American to practice law in Alachua County, Florida (Crabbe, 2008, April 4).

In 1965, at a critical junction in the American Civil Rights Movement, Stephan P. Mickle received a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science from the University of Florida, becoming the first Black student to graduate from the University. He received a Master of Education from the University of Florida in 1966. In addition, he received his Juris Doctor (J.D.) from the Frederic G. Levin College of Law at the University of Florida in 1970. In doing so, Mr. Mickle became the second Black student to graduate from the University of Florida’s Levin College of Law; the first graduate was Mr. W. George Allen (1936-2019) in 1962 (Dobson, 2019). A civil rights activist and lawyer, W. George Allen was born in Sanford, Florida to Lessie Mae Williams and Fletcher Allen. According to his autobiography, Allen grew up with his mother and stepfather, Bruce Brown, in segregated communities in Florida (Allen, 2010). He graduated from Crooms High School, going on to graduate from Florida A&M University, one of the Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), in 1958. Prior to his graduation, Mr. Allen worked for the U.S. Army Intelligence, where he was the only African American. Although he was accepted to Harvard School of Law, he chose instead to become the first Black student at the University of Florida Levin College of Law. He had a successful legal career and public service in Broward County before his passing in 2019 (Tinker, 2019, November 19). In October 2012, the Levin College of Law and its Center for the Study of Race and Race Relations, the University of Florida Association of Black Alumni, and the University of Florida Alumni Association held a tribute for Allen, marking the 50th Anniversary of his graduation (Figure 8.1). Yet in interviews through the years, Allen recalled the discrimination he endured while studying in Gainesville, Florida (Dobson, 2019, November 8).

Stephan P. Mickle was an attorney in the Office of Legal Services at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission in Washington, D.C. in 1970 and had a private practice in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. In 1971, Mickle became an adjunct professor at the University of Florida College of Law, a position he held for 38 years. He was also a special assistant public defender for the Eighth Judicial Circuit in 1974. He was a judge on the Alachua County Court from 1970 to 1984 and was a circuit judge of the Eighth Judicial Circuit from 1984 to 1992. In 1993, he began serving as the first Black federal judge in the First District Court of Appeal.

President Bill Clinton nominated Judge Mickle to the United States District Court for the Northern District of Florida on January 27, 1998, to the seat vacated by Maurice M. Paul. Judge Mickle was confirmed by the U.S Senate on May 14, 1998. He took the oath of office from Chief Judge Joseph Hatchett of the U.S. Court of Appeals on August 28, 1998 (Figure 8.2). He served as Chief Judge from 2009 to 2011.

Judge Stephan P. Mickle’s career was marked by many “firsts” as reported by several sources, including Wikipedia (2020):

- First African American to serve as a federal judge in the United States District Court for the Northern District of Florida, May 22, 1998 – June 22, 2011.

- First African American to receive the University of Florida’s Distinguished Alumni Award in 1999.

- First African American to serve as Adjunct Law Professor at the University of Florida for 38 years.

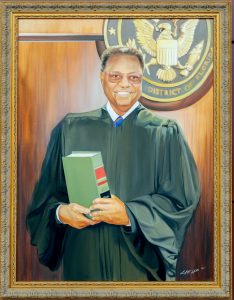

- First African American to be honored by the Levin College of Law at the University of Florida with an unveiled portrait, which now hangs at the Advocacy Center of the College of Law.

On October 23, 2020, the Levin College of Law at the University of Florida—in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic—organized a virtual “Celebration of Life and Career of Judge Mickle.” The occasion was the unveiling of the Portrait of Judge Mickle (Figure 8.3). Many signatories were present at this special event, which was presided over by the Dean of the College, Professor Laura A. Rosenbury.

Mrs. Evelyn Moore Mickle, the wife of Judge Mickle, was in attendance. Ms. Evelyn Marie Moore Mickle was born in 1947 to Reverend Frazier and Gretchen Whittington Moore and is a native of Suwannee County, Live Oak, Florida; she was the 11th child of 15 children. Her parents were farmers; her father was a pastor and school bus driver and her mother was a wife and homemaker. Evelyn and Stephan Mickle are the parents of two daughters and two sons, and the grandparents of five grandchildren.

Evelyn Moore Mickle was the first African American student admitted into the College of Nursing at the University of Florida and the first African American student to graduate with a Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) from the College of Nursing in 1967. Mrs. Mickle’s experiences as a pioneering African American female student were harrowing to say the least; she endured a tremendous amount of racism. Mrs. Mickle shared her experiences as a student at a 2009 public program by the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program, Florida Black History: Where We Stand in the Age of Barack Obama: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mkeBwBeKY7A&t=2667s.

A licensed registered nurse with the Florida State Board of Nursing, Mrs. Mickle’s career experiences include a wide range of areas in health care: psychiatry, pediatrics, internal medicine, juvenile detention, day care, hospital and clinic supervision, school nursing, community health nursing, etc. A commemorative brick was laid in her honor as the first African American graduate in Nursing from the College of Nursing at the University of Florida. The brick was placed at the North East corner of the University Auditorium. Mrs. Mickle currently serves in the Gainesville community as Mt. Carmel Women’s Ministry Leader (Interview. 2020, January. Samuel Proctor Oral History Program).

Reflections

As indicated earlier, Professor Laura A. Rosenbury, Dean of the Levin College of Law at the University of Florida, presided over the ceremony to unveil the portrait of Judge Stephan P. Mickle. Several colleagues, former law clerks, law students and friends of the Mickle family came to share their reflections about Judge Mickle. Here are a few select edited reflections. We begin with Dean Rosenbury’s remarks:

Dean Laura Rosenbury: It is my honor and privilege to welcome you to this virtual celebration of the life and career of Judge Stephan Mickle. We have an outstanding group of guests who will be joining us today, and I am so happy that Judge Mickle and his family are also able to be here with us to enjoy it all. As a matter of housekeeping, since this is a Zoom presentation, please remain on mute for the duration of the program to limit interruptions. We also recommend selecting the speaker view on the upper righthand corner of your screen for the best viewing option. 2020 has undoubtably been a year like no other. Everything about the way we live and work together has had to change and adapt to the logistics of a new normal. When I reflect on these past months, I have to admit, they’ve been very difficult, but I know my difficulty—our difficulty—is nothing compared to what life must have been like for Judge Stephan Mickle when he first arrived at the University of Florida in 1962. Although he ended up becoming Judge Mickle years later, Stephan Mickle first had to do what many of us have never before experienced in our lives—being the first. The first to forge ahead when no one else looked like him on the University of Florida campus; the first to persist, despite the challenges and obstacles that Stephan Mickle faced as a young Black man at the University of Florida. In 1965 Stephan Mickle became the first African American to earn an undergraduate degree at the University of Florida. He then earned a Master’s degree in education in 1966. And in 1970, Stephen Mickle became the University of Florida’s second African American Law School graduate. He began his legal career here in Alachua County, and he continued to be the first at each step of the way. During the next hour, we are going to hear from several people who will share stories about their relationship with Judge Mickle and his impact on their lives, an impact that has extended to so many of our lives, our careers, and our community. We will begin our program with some context about Judge Mickle’s legacy at the University of Florida, context that will be provided by Marna Weston from Oak Hall Academy and UF’s Samuel Proctor Oral History Program. Marna, the floor is yours.

Marna Weston, faculty member at Oak Hall Academy and UF’s Samuel Proctor Oral History Program.

Marna Weston: Thank you very much, Dean Rosenbury, for your incredibly gracious introduction and for appropriately framing the occasion for today. Distinguished barristers, Judges Turner, Hinkle, and Walker, Chairman Cunningham, our moot court president, Ms. Love, the Mickle family, ladies, and gentlemen, a beautiful sunrise welcomed us this morning and led us each to this midday service, and in our own individual ways we all celebrated it. For myself I praise God. I praise God for waking me up this morning, praise God for this beautiful ceremony where the University of Florida recognizes African American achievement and excellence. I praise God for the individuals and the family that we celebrate with this unveiling today. I was invited to provide context for these festivities. Context is an interesting word. I hope over the course of these brief moments that I’m able to provide some context to such a great life. Now you know I was raised a church-going boy. I was son of Baptist ministers, the child of children of the movement and part of the movement—the strategy that was used was to build courage for the obstacles people would face with the freedom song, a mixture of common religious hymns and secular music. As the elders would put it, to deliver the lesson, we need at least one piece of song. [Singing] “I woke up this morning with my mind, my mind it was stayed on freedom! Oh, woke up this morning with my mind, my mind it was stayed on freedom. Oh, woke up this morning with my mind, my mind it was stayed on freedom! Halle-lu, Halle-lu, Halle lu-jah!” I woke up this morning with the honor of talking about Judge Mickle, but to honor the man, we must honor all of the cloth in the tapestry that made him. We’re gonna hear today of humble beginnings. We will hear today of being welcomed and not welcome. We already have some from our Dean. We will hear of family and of love, and there are undoubtedly stories of professional achievement from this honored list of distinguished guests, and we hunger for them on this day as we honor Judge Mickle. Eleven years ago, when Dr. Machen tapped Florida Bridgewater-Alford, Dr. Glover, and our brother in all things historic, Dr. Paul Ortiz, the first African Americans at UF, and when the Black Alumni Association took the occasion of a home football game to gather our Black alumni, I was able to speak with W. George Allen, Dr. Reuben Brigety, Little Jake, and most importantly Judge Mickle and Mrs. Mickle. From that meeting with Mrs. Mickle, our first African American graduate from the nursing school, I first learned of how the University of Florida of that era was really not the University of Florida of the era that we enjoy today. The institution did not celebrate diversity. The institution did not acknowledge the graduation of Black students or invite them to join the Alumni Association as—of course—we do now. Mrs. Mickle shared with me a narrative of exclusion and painful feeling, but she also shared a life with the man that we recognize and honor today. And of course, by way of doing so, we also honor her. The Dean has already indicated how Judge Mickle was the second African American Law School graduate and the first African American undergraduate. He was nominated by President Clinton, and from that Judge Mickle became the first African American chief judge of the Northern District of Florida. Now today, those who follow me will have more interesting anecdotes on that. So, I’m going to allow them to speak to that series of firsts that happens statewide, nationally. I’m going to leave some water in the well for them. From my humble place I’m here and providing context. I’d like to draw your attention for just a moment to the what-ifs. What if Constance Baker Mobley and Charles Hamilton Houston had not been there to advocate that Black students attend law schools in their own states? It was the custom before the 1960s, for the Board of Control in Florida to offer to pay the most qualified Black student advocates to go to schools in other states. What if there had been no Constance Baker Mobley or Charles Hamilton Houston? What if Virgil Hawkins had not given up his rights to attend the University of Florida? After the struggle of struggles, one that probably warrants, you know, a historic marker from down in Okahumpka to the University of Florida. But if he had not done what he did—What if there had not been a George Starke Jr. or a W. George Allen to proceed a Stephan Mickle, who would come here, just to struggle, which he and his wife, both did? How we remember our firsts is equally important to what could have been. And I want to thank you, Mr. Hawkins for all that you did that made Stephan Mickle and Mrs. Mickle possible. Today, we’re celebrating Judge Mickle while he’s here with us, as we should. Let’s remember that Mr. Hawkins received his degrees after he was gone. But what if the UF Law School did not have a Stephan Mickle as a student? What if there had never been a President Clinton to nominate him? I mean, if you think about it, to place it in context, outside of President Bush, not knowing how much a loaf of bread and a gallon of milk costs or Ross Perot having all those charts… That leadership that we are celebrating today might have been lost. Elections have consequences. Instead, a marvelous tapestry will be unveiled today, and we will celebrate a meticulous, professional, and immaculate career in service that was built. And this community has been served exceptionally by Judge Mickle as an attorney, as a jurist at every level. And now, more than ever, the finest legal degree granting institution in America at the flagship institution, in the State, can say thank you. Judge Mickle, we love you, we respect you, and now a permanent symbol of that affection is being offered, and it is important to have a permanent symbol, because the absence of that symbol could say so much more. Its presence assures an understanding of the value that you and your family hold and the love that you hold in all of our hearts. Judge Mickle, Mrs. Mickle, your daughter Stephanie, the entire Mickle family. We thank you so much for your sacrifices and your struggles. And I’m reminded of the words of another song that resonates from Judge Mickle’s career, it’s a song that my Dad really enjoyed; “If I could help somebody.” [Singing] “If I can help somebody, as I travel along, if I can heal somebody, with a word or a song. If I can show somebody he is traveling wrong, then my living shall not be in vain.” Thank you, Judge Mickle for having a life we’re celebrating, one not in vain. One of service and purpose to the people, not only of our state but to the entire nation. Thank you.

The Honorable Larry Turner was Judge Mickle’s classmate and longtime friend from the class of 1970. Larry is also the founding partner of Turner, O’Connor, and Kozlowski.

Larry Turner: Thank you Dean. I appreciate this opportunity. I especially appreciate the opportunity to speak about my friend Stephan Mickle, who I have known since law school. In fact, we met in law school. I was a year up ahead of stuff until I got married and had to work for a year, until my wife completed her undergraduate degree. In the meantime, Stephan entered the law school and we graduated together. We were, at that time, friendly, but we had not become friends. That is, we didn’t spend much time together. However, towards the end of law school, we began doing that. We were part of the study group for the Florida Bar Exam. Florida Bar Examination in those days was essay predominantly. It was a three-day exam, and we had to go as I recall to Miami to take it. Stephan and I shared—we wrote down together, we shared hotel room—and we studied, and we studied, and we studied. At those study sessions is when I first got impressed with Stephan for who he really was and what he was really like on a couple levels. First, Stephen was always the best prepared of all of us. He came in prepared. He had reviewed the information, he understood the information, and he taught us the information. I credit Stephan with getting me through the bar exam. So, Stephan, thank you for helping me pass the bar exam so that I could have a career as a lawyer, a short time as a Judge, and then as a lawyer again. The vernacular of the day was he “carried me” through the bar exam. And frankly, without his help, not sure I would have made it. We found out—I found out years later, he found out more quickly—from one of our study partners, McFerrin Smith also a judge later on, that the three of us had scored in the top 10% of the class, the people who took the bar exam that year. So, I thank you for that as well. You made me look good. Stephan, after graduating in 1970, came to Gainesville in 1971 having worked for the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission for a while. And Stephan, in his own quiet and powerful way, was always a barrier breaker. And the first barrier I was aware of him breaking outside of being the second Black graduate of the law school and so forth, was when he came to Gainesville to be a member of our local Bar. The local Bar Association in those days met at the Gainesville Golf and Country Club, and of course the Gainesville Golf and Country Club was a segregated, all-white institution and simply did not permit people of color—African American or otherwise—to be there unless they were in the service industry of some sort. Well, some of us, myself included, younger lawyers, resented that, we didn’t think that was a good policy to have. So, when Stephan came to Gainesville, we now said, “What are you going to do? Where are you going to meet now? Are you going to tell him he can’t join our Bar Association, or he can join, but he can’t come to our meeting or lunches?” It created a dilemma. So, they took it to the Board of Directors of the country club, many of whom were members of our Bar Association. And the Board of Directors said, “Well, gee, I tell you what, we’ll let him come, he can come into the building and he doesn’t have to come in the back door. He can come in the front door. However, he must go directly into the dining room, have his luncheon, and leave by the front door. He’s not to go anywhere else in the building.” So it was that kind of in-your-face ugly stuff, even then among professionals and semi-literate people. I was told I have three to five minutes. I’ve got a timer go in here and I’ve been over four already, so I’ll keep cut this short. One of Stephan’s lasting legacies is that he and a few more of us, the Young Turks, we called ourselves, saw that people did not have the ability to hire lawyers, except in the criminal justice system, of course, where there was a public defenders’ system. And, as a result, often failed in any kind of legal process they were involved in because they didn’t have representation and of course they didn’t know how to navigate the system of law. So, we got together a group of volunteer lawyers, again, the Young Turks plus Claire Gehan—who is another legend in her own right, the first woman to graduate from the University of Florida College of Law—and Claire and the rest of us got together and we formed a volunteer group of lawyers who would… We got someone to donate a space that we could use one night a week as a storefront where we could meet with prospective clients, and we would take turns meeting with prospective clients there. And then we take them back to our office eventually and represent them pro bono. Stephan was one of the first people to step forward for that he was one of the bulwarks of that. He was always making breaking down barriers and kicking in doors, metaphorically. That storefront today is Three Rivers legal services. It’s got services in 17 counties, has offices in Jacksonville, Lake City, and Gainesville, and employs over 50 lawyers. I’m sorry, 24 lawyers, total staff of 50—one of his legacies that many people don’t know about. But for Stephan Mickle, Three Rivers Legal Services would not exist today. There is more! There is much more I could tell you, but I see my time is up. So, let me close with this. We know the proverb, all of us, “behind every great man, there’s a great woman.” Evelyn, I see you there. Evelyn has been, and continues to be, that woman for Stephan, and she, in her own right is a great person, as many of you know. She has always been with him, behind him, next to him. And frankly, oftentimes leading him. So, my dear friends, Stephan and Evelyn please accept these comments with my respect, my admiration, and my love, to both of you. Thank you.

Judge Robert L. Hinkle, the Senior Judge of the United States District Court for the Northern District of Florida.

Judge Hinkle: Good afternoon, Dean, and other guests. Perhaps you’ll forgive me if I start with a personal note to Stephan and Evelyn. It’s good to connect, even over the computer screen, with COVID shutting down court events and travel. It’s been too long. Mary Lou and I send our best. When I was asked to be involved in this program, I was very honored, and of course immediately said yes. I figured we have a good man, and a good family and a good school—bound to be a good event. It’s always good to connect with the University of Florida. University communities are special. They always engender loyalty, but none more than the University of Florida. Gators are a proud lot. And if you’re double Gator—well, that’s really special. Judge Mickle has always been proud of this University, and the University has always been proud of him, and rightly so. We had a historian explain some of that, and that’s proper that an explanation come from historian, because to most people in attendance, the idea of being the first African American in school is a matter of history. For most in attendance, by the time they entered school, there was already at least some integration, so stories about being the first were historical. But for Judge Mickle, and Larry, and me and a couple of others, we went through it. We started at segregated schools, and by the time we got out of school, there was at least some integration. The one thing I would say about that is I’ve come to understand that this was a lot harder than most of us realized at the time. Certainly, a lot harder than we whites realized at the time, but I think harder than most African Americans realized at the time. And much harder than people realize, now. It took a special kind of person. I doubt if Judge Mickle ever told very many people that, “Yeah, this is really hard,” and anybody let on, because it does take that special kind of person and the kind of person that was able to do this probably didn’t go around saying, “well, by the way, this is really hard.” We all owe a debt of gratitude to those who did this, it needed to be done, it needed a special kind of person to do it. And I had a couple of quick notes about Judge Mickle. As a judge, he ran a good courtroom, just the right atmosphere, just the right decorum in the courtroom, always got very high marks for how he ran the court room. And then I tell you one story about us as his colleagues. We were at judges’ meeting one time. As judges, we sometimes get together and talk about how we’re doing our job, and you can share notes and so forth, and a new judge asked a question about sentencing. Judge Mickle didn’t speak up a lot of meetings, but if he spoke, he had something to say. And he took that question they responded to it on the merits. But then he said, “And you’re gonna to have to live with every one of those sentences.” Sentencing is the hardest thing we do. And I think that statement captured his approach as a judge. He knew it was important and he communicated that very well. Criminal cases wind up with motions. Years later, the law changes. There’s been a First Step Act, now we’re dealing with a lot of Compassionate Release questions, and so I would sometimes, since Judge Mickle has been retired, get motions directed to cases that he handled the sentencing. And when I pick up one of his cases, I always know that the sentence that he imposed was no accident, that he took it seriously and that this was his considered judgment. That I think is a story about how he approached his career as a judge. So, Judge Mickle, I end by saying congratulations on today’s event and portrait, even more on your outstanding career, and thank you for doing what you’ve done.

Midori Lowry, Judge Mickle’s former law clerk, is currently serving as an assistant Public Defender for the Eighth Judicial Circuit.

Midori Lowry: So good afternoon, everybody. My name is Midori Lowry and I am a 1994 graduate of the University of Florida College of Law and I’m speaking here today because I had the immense honor and privilege to be Judge Mickle’s law clerk for 16 years. If you want to know some things about Judge Mickle, some great things, I can tell you. And it’s not just about his legal mind, his demeanor on the bench, or his commitment to his work, but also what he was like as a person, a very noble person. And what stood out very prominently is Judge Mickle has a great love for his family. He’s been married for over 50 years to Mrs. Evelyn Mickle, who you’ve heard in her own right is great, the first Black graduate of the nursing school in 1967, at the height of the Civil Rights Movement. And Mrs. Mickle was the one who picked the artist, Carl Hess, to paint Judge Mickle’s portrait, and you’ll get a chance to see she has great taste, because that is a beautiful portrait. Judge Mickle has three children and a nephew who he raised, and Judge Mickle is a very devoted son to his mother and father who were also prominent members of the community. He lived in the same neighborhood with them, the same neighborhood that he grew up in an East Gainesville. One of the rules for our office for me and the other law clerks was to get Judge Mickle the message immediately whenever family members called. Judge Mickle was a very busy man, extremely diligent in his work, but his family took priority. And I can remember at times, his daughter Stephanie would call, or his son Pierre, or his other daughter, Amy, and Judge Mickle would answer the phone, and I could hear him say “Hi, Pumpkin,” or “Hi, Amy” or “Hi, Pierre.” The love in his voice was very genuine, very true, very caring and it was just wonderful to see that, and he brought that same spirit to his work. He cared very much about making the right decisions and getting through to people about really what matters most. And I’ll let you know in Federal court, there’s usually a gap about 60 days between taking a plea and the date of sentencing, and when taking a plea, it’s customary to ask defendants basic questions about their family, like how many children do you have. Judge Mickle would sometimes make it a point to ask the defendant the names and ages of their children, sometimes even how to spell their names, and I hope you can imagine how sobering that was to stand before Judge Mickle who looks very imposing, and being reminded that children—your children—are important to him, and they should be important to you. Now Judge Mickle had very high standards. He ran a very tight schedule in court, and he expected everything to run smoothly, and it was amazing because he never yelled. He never banged this gavel. You could just tell what was expected. And when you look at the portrait, I think the artist captured the essence of that in the way Judge Mickle is holding that book in his portrait. We had a case once were a lawyer actually fainted in court, once pre-trial conference when Judge Mickle was discussing the schedule. He did recover and tried the case the following month, but you could tell when you’re standing in front of Judge Mickle that there was no nonsense and there was a sense of his greatness there. Let me tell you something else. It’s kind of fun working with Judge Mickle. Judge Mickle had an all-female staff, with the exception of one term law clerk, our beloved Ronald Layton. But other than Ron all the other law clerks and courtroom deputies, Cheyenne Starke and Carolyn Graham, were female. And we all got along. And that’s what happens when people care about each other and about doing the right thing. And I credit that to the tone Judge Mickle set in the office, and also to Rebecca Butler who was Judge Mickle’s judicial assistant in State court and throughout his tenure on federal court and almost throughout his entire career. There was a real family atmosphere in the chambers. Judge Mickle would invite us to his house for Christmas, or he would have us over he said to express his appreciation. I remember one year in particular, when his neighbor, Mrs. Morgan, came over and played the piano, and we all sang Christmas carols, and it was just wonderful. Judge Mickle always had an open-door policy in his office, literally, his door was always open. And we could go into his office and talk with him and ask him questions. Sometimes I’d walk by and I’d ask Judge Mickle what he was doing and he would say, “Dori, I’m contemplating the form of the good.” The form of the good—that’s from Plato. The form of the good is what allows us to see and understand justice, truth, equality, and beauty, and it is said to exist outside space and time, and is eternal, perfect, and changeless. And I took that as Judge Mickle telling me that he was praying, because he was very devout and he prayed a lot. One of the things that I learned from Judge Mickle is a Bible saying. It’s “don’t light a candle and put it under a bush.” And it means that goodness that is done in this world should be acknowledged, celebrated, emulated, because no matter how hard things get, how dark things are, the light will always shine. So, I think it’s very fitting that Judge Mickle’s portrait is here at this law school, his alma mater, where people will see it, and I hope they’re inspired by his life. Thank you.

Chief Judge Mark Walker from the United States District Court for the Northern District of Florida.

Chief Judge Mark Walker: Thank you, Dean. I’d like to correct the record from the get-go, based on the technical difficulties. I’d like to clarify, I did not get my undergraduate engineering degree from FSU, it was purely an accident that I wasn’t able to unmute the microphone. As many of you know I succeeded Judge Mickle when he took senior status. That means I’m sort of like the quarterback who followed Tim Tebow at UF. It’s a difficult thing to follow a legend. And I’m humbled every day, recognizing that I followed a legend like Judge Mickle. In 1956, about 10 years before Judge Mickle got his master’s from UF, the United States Supreme Court wrote, “there can be no equal justice, where the kind of trial a man gets depends on the amount of money he has.” For 50 years, first as a lawyer and then as the judge, Judge Mickle has done his very best to ensure equal justice under law and his efforts have benefited generations of Floridians. Proverbs teaches us that a good man leaves an inheritance to his children’s children and there is no doubt Judge Mickle is a good man. His children and his grandchildren are blessed to have been raised by a man who instilled in them a passion for justice. Because of the example Judge Mickle set for them. They understand, as Justice Marshall once said, “where you see wrong or inequality or injustice, you must speak out.” For those who clerked for Judge Mickle, appeared before him as lawyers, or served with him as judges, we are all beneficiaries of his wisdom and his great example. And it is only right and proper that we honor him today. But here’s my hope, and I know we’re here to talk about Judge Mickle, but in terms of his legacy, I hope that after today every law student that walks by Judge Mickle’s portrait, pauses, and takes the time to reflect upon his life, and I hope after they do that, that they’ll commit themselves to follow his example to do their very best to ensure equal justice under law. As lawyers and judges, we can never do more, and we should never strive to do less. Congratulations Judge Mickle, I can think of no judge more deserving of this honor and I’m grateful for the opportunity to speak this afternoon. All the best. Thank you.

Elizabeth Rowe, the Irving Cypen Professor and a distinguished teaching scholar here at the Levin College of Law.

Elizabeth Rowe: Thank you, Dean. In thinking about what I would say today, I realize that we have the span of several generations here to celebrate Judge Mickle, and that how each of us processes, the significance of this event will vary. We got here in 2020: a year that will definitely be in the history books for all kinds of reasons, and a year when most of our current law students are people who were born in the late [19]90s. Generation Z is already in law school. So, having that in mind, and thinking about what Martin Luther King said, that “we are not makers of history, but we are made by history,” I’d like to frame this occasion with a little bit of history and also to consider how as individuals, especially since we’re here to recognize and honor an incredible individual, each person shapes others both directly and indirectly. So, as you’ve heard, it was 1965 when Judge Mickle graduated from the University of Florida. This was the same year of the passage of the Voting Rights Act. In the same year in which Malcolm X was assassinated. A year later in 1966 he received his master’s from UF. And then the following year, another great, his dear wife Evelyn Mickle, was also the first in graduating from the College of Nursing. But that year was also the year that Thurgood Marshall was appointed to the US Supreme Court. The following year, 1968, Martin Luther King was assassinated, and Senator Robert Kennedy was assassinated. Two years later, continued, and we mark the occasion of Judge Mickle graduating from the UF law school. That was the year 1970 when the Black Law Students Association was established and named after George Allen, the first Black person who graduated from the UF law school. It was also the year that the UF faculty became integrated and seven Black law professors were hired. In 1972, Judge Mickle started teaching as an adjunct professor at the law school. And this is a position that he held continuously, until very recently, when he retired. And all of this, a lifetime’s worth, was all happening before I was even born. And if we fast forward to today, as just one example, and I’m sure there are so many others, I see how the circle of my life so many years later in my career has reflected Judge Mickle’s. I too graduated with a bachelor’s and a master’s from UF in the early [19]90s and received the law degree. I’ve also had the privilege of being a member of this distinguished UF law faculty, including with five other Black tenured faculty colleagues, as we prepare hundreds of students each year to become lawyers. I met Judge Mickle when I was an undergrad at UF. I served as an intern in his chambers, and it was that experience and his guidance that convinced me to apply to law school. Over the years, he would continue to be an influential presence in the biggest moments of my life. I called him within minutes of receiving my acceptance from Harvard Law School. He officiated my wedding. He and Mrs. Mickle attended my law school graduation, and he was also one of the first people I called when I was considering leaving private practice to become a professor. As I have gotten older and evolved in my career, in my life, I have come to gain even greater appreciation for Judge Mickle. Even more than who he is as a person, what he symbolizes, and his many firsts, and the many doors he has opened has had lasting impact on each of us both directly and indirectly, and it continues to multiply. So many of us stand on Judge Mickle’s shoulders. We can only aspire to have the strength of character and determination that he displayed all these years, as we encounter our own challenges in life. It’s difficult to put into words, what it will feel like for so many of us who walk on this campus each day to see a portrait of a person who represents so many firsts, and who embodies for all of us, the ideals of excellence and integrity, grace and courage, compassion, and strength. This itself is yet another first, which I hope will continue to remind and inspire this great law school community to even greater heights. I thank Dean Rosenbury, our trustees, our faculty, Mike Farley, the Mickle family, and especially Judge Mickle, for yet another historic occasion.

April Ziegler Walker, 1997 graduate of UF Law, who now practices with Upchurch Watson, White, and Max.

April Ziegler Walker: Thank you, and good afternoon to everybody. First let me say that sitting through Midori’s comments brought back a lot of memories, memories that I had already begun to think of as I began preparing for today. And I found myself a bit overcome with some emotions as I thought back that indeed chambers was very much like family. Judge Mickle indeed treated us like family. And I’m so appreciative of that, and I thank you Dori for those words. I thank you all for the opportunity to share in the celebration. I have to say, I think I may have been somewhat of a wisecrack during my years. I clerked with Judge Mickle from 1998 into 2000 and I’m watching his screen. And I think my goal will be to garner what I think is a smile or laugh behind his mask. So, let me share what I prepared, which will hopefully keep me from shedding tears, in the next three minutes. I thought back that I had the distinct honor of being Judge Mickle’s very first law clerk hired in [19]98, which was so exciting for me. I had started my private practice. I was in my first year of law school and when the door opened to interview with Judge Mickle and clerk for him, man, I raced through that door, because what law school student doesn’t want to work for a federal judge. Frankly, the value of that clerkship would be lost on me until some years later. So, let me just say that because I was the first hire, I was also consequently the first to be pulled out of chambers. Judge Mickle put me out and gave my title to Dori, and all in good jest. It was great. I can think of one thing Judge Mickle used to say, and I think he may have had something on the wall. He used to say, “poor planning on the part of an attorney doesn’t create an emergency on my part.” Something to that effect. And I have to tell you, because I had already started practicing, I used to rush in. There were days that I would be reading through an emergency motion. And I’d be like, “Judge, we got to decide this. We got to get to this!” And Judge, being Judge, knew that just because an attorney says it’s an emergency doesn’t mean it’s really an emergency. So, I did learn to govern myself by that as a lawyer. Years later, I’m glad I learned that lesson first as a clerk. But earnestly, I remember Judge Mickle as always being mild-mannered, steady, and deliberate. He always carried himself with dignity and self-respect, which we expect of a judge. But remarkably, I have to say in those two years I saw him treat everyone with respect and dignity. Everyone. During those years, we worked in Gainesville, but we were also responsible for the Panama City Docket. And so that’s two courthouses of employees, security guards, staff, US Marshals, federal probation officers, waitresses, and lawyers, litigants—every single person Judge Mickle treated with dignity and respect. I never heard him say a harsh word. He was never arrogant, nor was he ever brusque or abrupt, and I have to say that is something else. He treated people well. I practice litigation for a lot of years I returned to the law firm I left, eventually to be a partner there and I love litigation. I decided, some years later to devote my legal work to conflict resolution and alternative dispute resolution, which I do now. And I must say, I think it’s because I understand the impact we have when we treat each other well, and as lawyers, whether we’re in court or not, how we are guardians and of this process, whether it’s in court, whether it’s in mediation, people look to us in ways that we don’t realize as representatives of our profession, and I’m just so thankful that Judge Mickle had given me that early example of treating people well and conducting myself and ways of dignity and grace. So, Judge Mickle, I would say you are a trailblazer, but frankly, you’ve blazed many trails. You’ve impacted so many people, lawyers, and non-lawyers alike, in so many positive ways, and so I humbly say thank you for everything that you did for me, thank you for everything you’ve done for the profession, for your family and of course to Rebecca and Midori. God bless you all. Thank you Judge.

Nick Zissimopulos, a 2002 graduate of UF Law, and now managing partner of Glassman and Zissimopulos here in Gainesville.

Nick Zissimopulos: Thank you, Dean Rosenbury, Judge Mickle, and Mrs. Mickle, hello and thank you for this great honor to be able to say a few words today. I do need to correct the record. I was not a clerk. I think if anyone goes back and looks up my grade point average you would quickly see that I was probably not eligible for that. So, I don’t want anyone to be confused with that, but for lawyers like me, we learned first about Judge Mickle from the stories, people like my trial practice instructor, Larry Turner. And from the stories what we learned was that Judge Mickle was a legend. And that’s the way he was talked about whether it was his groundbreaking work as a student, or his brilliant legal career, or his work as a judge, at every different level in the state and them into the federal court. But when you get the chance to meet Judge Mickle, what we learned, and what I learned, is that in addition to those stories being completely 100% true—that he was a legend—I also learned that that he was a legend who was full of grace, and full of humanity, and full of kindness. That together is what made him such a special and unique man. I had opportunities to practice in front of judgmental as a criminal defense lawyer, and I can tell you that the words that April just spoke with the words that are on my paper here. The dignity that he showed folks. The lawyers in the room he would compliment and those compliments meant a lot at the end of the trial. The court staff, the US Marshals. And one of the things that I remember most having tried a handful of trials in front of Judge Mickle is that as you know in the courts when the judge would go in and out all the parties and all the lawyers and everyone would stand up as the judge came in and out, and we would stand up as the jury came in and out. And the judge would always remain seated, while the jury came in and out. But when the jury went back to deliberate, Judge Mickle would stand up and he would make a point of telling the jury that he was standing up for them as a sign of respect. I just remember that moment, and he would do that every trial, and it was something that stood out and it was an example of his humanity. After getting to know him as a lawyer practicing in front of Judge Mickle, I then had the opportunity to kind of get to know him as a teacher. And he has been an example to me of how to be a teacher in the law. He was instrumental in starting the trial advocacy program here at the University of Florida. It was wonderful because not only did it give him an opportunity to teach students, but it also gave lawyers in the community an opportunity to come in and be part of that. And every week three, or four, or five lawyers in the community would come and be guest judges. And I have fond memories of being a very young new fresh lawyer, coming into those meetings where we sit around with Judge Mickle and the other lawyers and his assistants, and we would talk about the class and what we were going to work on. And there were always refreshments. My memory is that there were carrots and cookies. I remember some carrots being leftover at the end. Always felt like it was a test, where you’re going to take the good snack or not-so-good snack. I think all the cookies eaten but the carrots are sometimes left behind. But just that we in those meetings when we sat around and Judge Mickle would sit there, and he would ask us all, “How are you doing, how’s the practice going, you know, how are your law partners?” He just he cared about us, and to have this legend show that sort of humanity was something. I have fond memories of watching him teach and watching him interact with students. And then when he retired, it was perhaps one of the greatest honors of my life, that I was able to continue on and help teach that class for some semesters what the class remained. And every single semester that I had an opportunity to teach the trial advocacy class, I made sure that I spoke his name because I wanted to make sure the students knew why that class existed and knew the legend that had created that class. And I think it is truly wonderful that there will now be this portrait so that his memory and his accomplishments will be known by the students that are there now and forever into the future. I thank you Judge Mickle for again, letting me be part of this, and I wish you all the best. Thank you all.

Anitra Raiford is a 2012 graduate of UF Law who now practices with Shook, Hardy, and Bacon in Tampa.

Anitra Raiford: Good afternoon, Gator family. It is a pleasure to be here today to honor one of my real-life heroes. Like most people with some success in their life, I could not be where I am without the help of others, many of whom are speaking on this call today. I stand on the shoulders of giants. But the biggest giant whose shoulders I stand on is without a doubt the Honorable Stephan P. Mickle. Since I am a graduate of the University of Florida and the University of Florida Levin College of Law, like Judge Mickle, I know that I owe my higher education to Judge Mickle’s willingness to blaze a path for so many people, including myself. I was lucky that the gifted education from Judge Mickle did not end there. And this is because he hired me to serve as a judicial law clerk for him. I’m very grateful that he selected me as the last law clerk hire for the 2012 and 2013 term because my experience working for him changed my life for the better. Working in his chambers was like attending a masterclass each day. I find myself modeling my career after his. For example, I find myself always being mindful and my cases that my clients’ money, liberty, and reputation is at stake, like Judge Mickle was always aware of in his cases when he presided over matters. Therefore, as an attorney, I always take my cases very seriously and I try my best to be a zealous advocate. I find myself serving the Bar Community in the UF Law community like Judge Mickle, who gave his time wisdom and resources to these communities, including by teaching classes at the law school like we just heard. I also find myself being able to remain steadfast toward my goals, even if I hit a little bump in the road. I say this because Judge Mickle taught me then that everything may not go my way in my career, but at the end of the day, things will work out if I have faith, work hard, and maintain my integrity. Today, if I face a hard time in my career, I remember this lesson. I remember what he overcame, and I know that because of Judge Mickle that I can overcome any hardship too. Judge Mickle, thank you for all that you have given to me, and congratulations on this honor.

Ebony Love is a current UF Law student. Ebony serves as the President of the Florida Moot Court Team and as a Law School Ambassador. Ebony was previously president of the W. George Allen chapter of the Black Law Students Association here at UF Law, and she now serves as the Southern Regional Chair of the National Black Law Students Association. Please join me in welcoming Ebony.

Ebony Love: Greetings, everyone. My name is Ebony Love and I’ve been asked to speak today about Judge Mickle’s legacy and what it means to me as a current student who live in the trail that he is blazed. But before I do that I want to talk about when I first met the Mickle family. Because of the Mickle family, I am a double Gator. In 2016 I was proud to serve in the Black Student Union as the Secretary of the Black History Month committee. In 2016 I learned about the story of Evelyn Mickle. It was then that I learned that Evelyn Mickle was the first Black student to graduate from UF’s nursing program. It was also then when I realized that Evelyn Mickle was never afforded her pinning ceremony when she was a student here at the University of Florida, simply because of the color of her skin. In 2016 we rectified that by giving her pinning ceremony and giving her flowers while she was still here, and today we rectify that as well, with this unveiling of the portrait that we’ll see in a few minutes. Before I came to law school I worked at the National Center for Civil and Human Rights. The museum has a saying called “Live the Legacy.” And the saying refers to Martin Luther King Jr. and the legacy that he left behind. When I think about Judge Mickle being a trailblazer, it’s because he lives his legacy. Because of Judge Mickle’s legacy at University of Florida being the one of the first Black students to graduate from the undergraduate program, and the first to graduate from the law school, I could become a double Gator, earning my history degree, and then also earning my law degree. His work in the Gainesville community is unparalleled because he is a charter member of the Atlanta chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity incorporated, which is the same fraternity that Martin Luther King Jr. belonged to. In my personal capacity, I’ve seen Judge Mickle at events, both on and off campus, always having a kind word and always willing to speak with anyone who has a question for him. One of my most profound memories of Judge Mickle is when he swore in former professor and now Judge Meshon Rawls. I looked around the packed courtroom, and I remember being overwhelmed with emotions because I could feel Judge Mickle passing the baton off to the next generation. Judge Mickle stood tall and regal in his robes, while Judge Rawls stood to his side in her salmon pink suit, which was a nod to her sorority. His voice came out soft but firm and the entire room held their breath as Judge Mickle administered the oath. Judge Mickle has taught us countless times how to leave and live your legacy. I could talk about his unwavering support to the W. George Allen chapter of the Black Law Students Association. But I don’t have to because it’s been permanently recorded by the Center of the Study of Race and Race Relations, and it also lives on in the memories that countless Black students from the University of Florida have had with Judge Mickle. I could talk about his dedication to the Gainesville community, but I don’t have to because the proof is seen through the current Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity alumni chapter here in Gainesville. I could talk about his lasting impact as a trailblazer on students like myself, but the proof will come on when we live in his legacy and we make a lasting and positive impact on the legal field. We will be excellent attorneys, we will be brave advocates, and one day we will be judges. Before I close, I was inspired by some of the previous speakers who came before us. Last year I did serve as a President of the W. George Allen chapter of the Black Law Students Association in its 50th year. During that year, we had a t-shirt, and I’m just going to read off what the t-shirt actually said, because I think that it is kind of sums up Judge Mickle’s legacy. On the front of the shirt, there were sayings that were associated with alumni and professors who have impacted Black law students here at the University of Florida. The shirt reads: “breakthrough like Hawkins, trailblaze like Starke, empower like Land, innovate like Nunn, build like Cash-Jackson, educate like Jacobs, challenge like Holiday, advocate like Rawls, mentor like Williams-Harris, leave a legacy like Allen, and inspire like Mickle.” Thank you Judge Mickle for inspiring the next generation of change-makers.

James Cunningham Jr., a 1978 graduate of UF Law and this year’s Chair of the Law Center Association Board of Trustees.

James Cunningham Jr: Thank you, Dean Rosenbury. Let me begin by taking you to a time and a mentality. The likes of African Americans were one time told that everything we did we had to do it impeccably, because our responsibility was to uplift the race. That’s a huge responsibility for anyone. But the fact that this responsibility was put on the shoulders of Judge Mickle and carried so well by his wife with him, as demonstrated by all the comments that have been made today, shows that there could not have been two better people to behave impeccably and to uplift the race. All of you assembled here now are here to say to Judge Mickle: “Well done.” Take this bouquet of flowers. Enjoy them. We’re here to say thank you, Judge Mickle. What you did mattered. It was important. And because of a time in which we live, we are missing the opportunity to be able to hug Judge Mickle. And, in every sense of the word, to be able to touch history. I grew up down in Ocala. And I referred earlier to uplifting the race. Judge Mickle and his wife were known to African Americans and Blacks in Ocala and held up as examples to little Black boys and Black girls there. The portrait that will be hung up today will continue holding him up as encouragement, as an example, to not just Black boys and Black girls but to everybody who comes through the University of Florida Levin College of Law. When one of his earlier law clerks talked about how she stands on his shoulders, let’s be clear about something. All of us stand on the shoulders of Stephan Mickle, because of the impeccable manner in which he has conducted himself. So, thank you very much, Dean. Thank you very much Judge Mickle and also to your family for all of the support they have given you. Dean Rosenbury, it is my honor to represent the 10 members of the 2021 Law Central Association Executive Committee and gifting to the College of Law his beautiful oil painting of our colleague, our friend, LLC, emeritus member Judge Stephan Mickle. Judge Mickle was indeed a trailblazer and a role model for all of us, and it is our hope that this portrait will be hung in the law college’s most visible and prominent space. And, so, if you will do us the honor now Dean Rosenbury of unveiling the portrait of Judge Mickle. [Applause]

Stephanie Mickle, daughter of Judge Mickle, is a 2004 UF Law School graduate.

Stephanie Mickle: I think Joe Genco may have had something to say about technology not working for the younger folks. So, thank you for bearing with me. To Dean Rosenbury, Chairman Cunningham, and members of the Law Center Association Executive Committee, Scott Hawkins, Greg Weiss, Courtney Graham, Judge Barksdale, Rebecca Brock, Derek Bruce, Brian Bergun, Lee Gun, Joe Thakur, Carter Anderson, and Mike Farley, and all who played a part today. We want to express our deep gratitude to you for making this day possible. Thank you very much. Our Dad has asked me to tell you how proud he is to be a graduate of the University of Florida and the University of Florida Levin College of Law. He wants you to know that he met our Mom, his beautiful wife, Evelyn, of 52 years during his first year of law school, and they lived in Married Student Housing and Corey Village right down the hill from the school. He wants you to know how proud he is at this portrait is being gifted and dedicated and how proud he is of this portrait will hang here, at the University of Florida Levin College of Law in the Martin Levin Trial Advocacy Center, which focuses on the education and training of trial advocacy, moot court trial team, the development of courtroom effectiveness skills, which, as many of you know, he loved teaching. And he has asked me to tell you how proud he is that his oldest daughter is a graduate of the University of Florida Levin College of Law as well. To each of the persons who share reflections, Judge Larry Turner, Judge Hinkle, Judge Walker, Anitra, April, Dori, Elizabeth, Nick, and Ebony. Wow, it is such a joy to hear your memories and reflections as friends, classmates, law partners, colleagues on the bench, clerks, students, and mentees. Thank you. To President Fuchs, Provost Glover, members of the Board of Trustees, the University of Florida Association of Black Alumni, and the entire Gator Nation. Thank you. To our dear family and friends who have been there throughout the years of various stages of our Dad’s career. Thank you. You’ve been in our Dad’s corner and that means the world. To Carl Hess, the artist who painted this wonderful portrait, thank you so much for capturing our Dad’s joy of teaching law and trial advocacy to hundreds of law students for 45 years since the inception of the CLEO program in 1971 at the University of Florida, in this beautiful rendering. And to each of you who are logged on from all across the country. Thank you for being here, virtually, to celebrate with us. We understand that there were more than 300 RSVPs here today. It is our delight to accept this portrait dedication, on behalf of Judge Mickle and the Mickle family. It has been interesting to reflect on the impact of our Dad’s integration of the University of Florida in 1962 and his legal career during this most unusual year of 2020. What we are experiencing right now in our country is unprecedented. We are simultaneously in the middle of a global pandemic, a national election, a Supreme Court nomination, and confronting centuries of racial injustice and inequality. Change is happening now faster than ever before. Black Lives Matter protests are taking place across the globe and our country is redefining what equality looks like. The University of Florida has the opportunity to be on the right side of history. This moment in time will without a doubt impact many generations to come. This is just one reason that the law school’s decision to dedicate this portrait of our Dad in the Martin Levin Trial Advocacy Center is even more meaningful. When people enter courthouses, classrooms, and law schools and see people who look like them, it shows them that the sky is the limit for what they can achieve in their careers. We have heard countless lawyers and litigants say that they knew if our if they had a case in front of our Dad, that he would treat the parties fairly without fail. They might not like the sentence or the verdict, but at least they had confidence that they would receive fair and impartial justice in his courtroom. And we are so pleased and delighted that our father’s legacy through this portrait will continue to be a part of moving this University forward. The Mickle family intends to continue that legacy. It is our family’s intention to endow a gift that would support the University of Florida’s law school’s recent scholarship for graduates of historically Black Colleges and Universities seeking to enter the legal profession, BALSA, and the University of Florida Center for the Study of Race and Race Relations. Thank you again, Dr. Rosenbury, the Law Center Executive Committee, and the Law School itself for this beautiful portrait.

Judge Stephan P. Mickle passed away on January 26, 2021 at his home in Gainesville. He was 76 years old.

Chapter 8 Study Questions

- Briefly discuss in 250-500 words some of the major issues presented in this chapter.

- What are some of your reactions to the struggles that Judge Mickle went through from being the first African American undergraduate at UF to gaining national prominence as the first African American to be appointed as a Federal Judge in Northern Florida?

- How would you characterize Judge Mickle and his wife, Evelyn Moore, as role models to all those who believe in Equal Justice for All?

References

Allen, W.G. (2010). Where the Bus Stops. Self-published autobiography.

An Oral History with Evelyn Moore Mickle [Interview]. (2020, January). Samuel Proctor Oral History Program.

Crabbe. (2008, April 4).

Dobson. (2019, November 8).

Federal Judicial Center. (n.d.). Retrieved October 15, 2020, from https://www.fjc.gov/

Samuel Proctor Oral History Program [Public Program]. (2009). Florida Black History: Where We Stand in the Age of Barack Obama. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mkeBwBeKY7A&t=2667s

Tinker. (2019, November 19).