Aluminum: Alcoa and Anti-Trust

Sean Adams

“There is no such thing as a good monopoly.” —Learned Hand

Abstract

This chapter uses Alcoa to tell the story of aluminum and antitrust. Although aluminum is quite common now, it was a very difficult metal to refine before 1888. One American company, Alcoa, was responsible for the rise in the application of aluminum to various markets. In order to increase production and profits, Alcoa grew in both size and scope, as did many American businesses during the early 20th century. Eventually, this company controlled two-thirds of the world’s supply. But as Alcoa emerged as a big business, federal policymakers considered it a dangerous threat to competitiveness in aluminum production. Using the doctrine of antitrust, the United States successfully knocked Alcoa down from its lofty place in worldwide markets in 1945. In doing so, those policy makers believed they had struck a blow for competitiveness, but the larger question arises: is a company that dominates the production of a single material bad in and of itself?

Introduction: Capping the Monument

Aluminum is the most common metal in the earth’s crust. It has amazing properties—it is resistant to corrosion, its low density means that it is one of the most lightweight metals, and it has a relatively low melting point, which means that it is easy to cast. We encounter aluminum nearly every day: it is in our beverage cans, our automobiles, planes, and in many of our kitchens. In fact, you might say that aluminum is the most commonplace metal of all. But this was not always the case.

Take, for example, the story of the Washington Monument. America had been planning to build some sort of memorial structure to commemorate the life of their first president, George Washington, since the 1780s. But, as with many monuments, the construction was subject to great controversy. One of the designs, for example, fell by the wayside when it came out that the Pope had donated stone from an ancient Roman temple for its construction. When anti-Catholic nativists found out about this, they slowed construction on the project in the 1850s.

Two decades later, construction resumed with a new design: a massive obelisk with simple, clean lines that formed a point at the top. Designers thought that a metallic pyramid on top could help with lightning and keep the edges sharp and clean. After considering bronze or copper, they decided instead to use a metal known for its attractive properties of conductivity and durability—aluminum. But they did not come to this decision because aluminum was cheap. In fact, this metal was quite expensive. In the 1880s, aluminum was about $16 per pound, or more than some American workers made in a week’s work, and the eight-inch-high, cast-aluminum pyramid cost a whopping $225—over $5,500 in today’s prices. The idea of using aluminum signaled the high value, not the ubiquity, of this metal. When it was completed, the Washington Monument was the tallest man-made structure in the world, standing at 555 feet, and it was topped with aluminum.[1]

Why is Alcoa Important?

At the dedication of the Washington Monument, aluminum was an exotic and expensive material. Casting the pyramid took several tries, and the manufacturer was worried that he might have use an aluminum-bronze alloy instead of pure aluminum. In fact, pure aluminum was so rare it really was more of a luxury good than anything else. Some of the royal families of Europe, for example, used aluminum dinnerware as a sign of their elite status.

The idea that an American company might unlock the secret of mass producing aluminum and find hundreds of applications for its use seems like a good one to us today; everyone likes technological innovation and efficiency. But what if this company grew so proficient at manufacturing and marketing aluminum that it controlled nearly two-thirds of the world’s supply? Is it acceptable to have a single firm hold that kind of market share? Should government intervene to restore competition to that industry? Those were the questions faced by a company called the Aluminum Company of America in the years following World War I. This firm—later renamed Alcoa—was so good at making and selling aluminum they nearly cornered the market. But were they too successful for their own good? That’s why the story of aluminum is wrapped up with the idea of antitrust, or the notion that a company that holds a huge market share operates as a monopoly. So why was Alcoa in such trouble?

This chapter will use the story of Alcoa up to 1945, when the federal government reduced the company’s market share through an antitrust case. This is an important example of how the political and economic context of a material can be critical in determining how it was made, what markets it serves, and how it becomes an important part of everyday life. Aluminum was not common at all before the 20th century, but Alcoa set out to change all of that. Along the way, they became almost too good at making and marketing aluminum. How is that possible? And why should we be concerned if a manufacturer is dominating markets, so long as that material is cheap and abundant? To understand this question we need to understand the notion of antitrust, and how Alcoa played a pivotal role in this uniquely American phenomenon.

The Origins of Big Business

Alcoa had its origins in the late 19th century, at a time when big businesses began to dominate markets. Because of technological and organizational innovation, increasing efficiency in production, and ruinous competition, prices fell steadily from the end of the Civil War to the mid-1890s. So the only way firms could control prices in the 19th century industrial economy was to control market share. Basically, companies became bigger and bigger in order to become price-makers and not price-takers; in other words, they didn’t want to leave their business to the whims of the marketplace. Instead, they sought to control their own economic strategies by growing in size and in scope, dominating the market for their goods, and setting their own prices.

These large industrial firms tried to centralize production and cut costs. There were two main goals. First, large firms built larger and larger factories in order to capture what historians call economies of scale. Basically, before the Civil War, most industries were subject to what economists referred to as “constant returns to scale.” This means that although a bigger factory might allow the production of more goods, the costs per unit were roughly the same; for example, if you put 100 looms in a factory, they wouldn’t necessarily produce cheaper cloth per unit than a single loom. After the Civil War, technological and organization changes brought “economies of scale,” which means that a large, expensive plant could produce goods more cheaply on a per-unit basis than small producers. Take, for example, flour mills and oil refineries: usually massive capital outlays are required to build such plants. Second, managers focused on increasing throughput within those factories. Throughput is basically a measure of the speed and volume of the flow of materials through a single plant or works. A high rate of throughput—which managers usually measured in terms of units processed per day—became the critical criterion of mass production. If a company did well on these measures, it likely was a large corporation with a huge physical infrastructure—a great departure from the small-scale businesses of earlier in the 19th century.

Checking the Trusts

Economists call a system in which a few large corporations dominate the marketplace “oligarchic.” Historians say that the Era of Big Business saw the rise of the “trusts,” which refers to Standard Oil’s legal maneuver to control over 90 percent of the oil refining business in the US economy via a system in which companies surrendered stock certificates—and control of their companies—to John D. Rockefeller via his Standard Oil Trust. Many Americans thought that the government should do something about the unchecked power of these trusts in industries like oil, sugar, beef, steel, and even whiskey. After all, if a company has a commanding market share, who is to say that they won’t jack prices up to monopolistic levels? This kind of control seemed undemocratic and, to many voters, un-American. So in 1890, Congress passed the Sherman Antitrust Act, which made “restraints of trade” illegal and aspired to break up trusts that undermined the public interest. But the statute was vague in defining these principles.

What is a “restraint of trade,” and how do you find it? The law didn’t provide any guidelines or examples, so enforcement of the law, by default, fell in the hands of the federal government to determine what a monopoly was and what wasn’t.

So how do you enforce a law that is so vague? Actually, the Department of Justice first used the Sherman Act against unions. Of the first 10 cases tried under the legislation, five were against unions that supposedly acted in “constraint of trade.” In 1895, the Supreme Court seemed to get the ideal opportunity to break up a trust. The American Sugar Refining Company acted in sugar in much the same way that Standard Oil did for oil. But worse, they controlled about 98 percent of market share by the 1890s. But even though the sugar trust dominated the American market, the Supreme Court, in United States v. E. C. Knight Co. (1895), made a very strict—and to be honest, very dubious—distinction between the Sherman Antitrust Act’s applicability to commerce and its applicability to manufacturing. The Court argued that antitrust laws really only applied to commerce, not manufacturing, and unless the American Sugar Refining Company built a factory that literally straddled a state boundary, the issue was for state courts, not the Supreme Court, to decide. Since the four major sugar refineries owned by the American Sugar Refining Company were in Pennsylvania, it was a matter for the Pennsylvania courts to decide.[2]

Big Business Gets Even Bigger

The way that American courts enforced antitrust meant that firms couldn’t form any kind of informal organization, like a cartel or trust. So horizontal integration offered the best strategy: you simply acquire your competitors and increase your market share. That way you create major barriers to your potential competitors because they’ll have to catch up in the race to achieve economies of scale. To pursue this strategy, many firms used mergers or the outright hostile acquisition of other firms. The first major merger wave in American history occurred during the years 1895 through 1904. Over this stretch of nine years, more than 2,000 previously independent firms disappeared. In 1899, there were about 1,200 recorded mergers—pretty huge considering that there were fewer than 100 mergers in 1896, fewer than 400 in 1900, and then back to fewer than 100 in 1904. The firms that emerged from this merger movement often dominated markets and continued to expand in size through both horizontal and vertical integration.

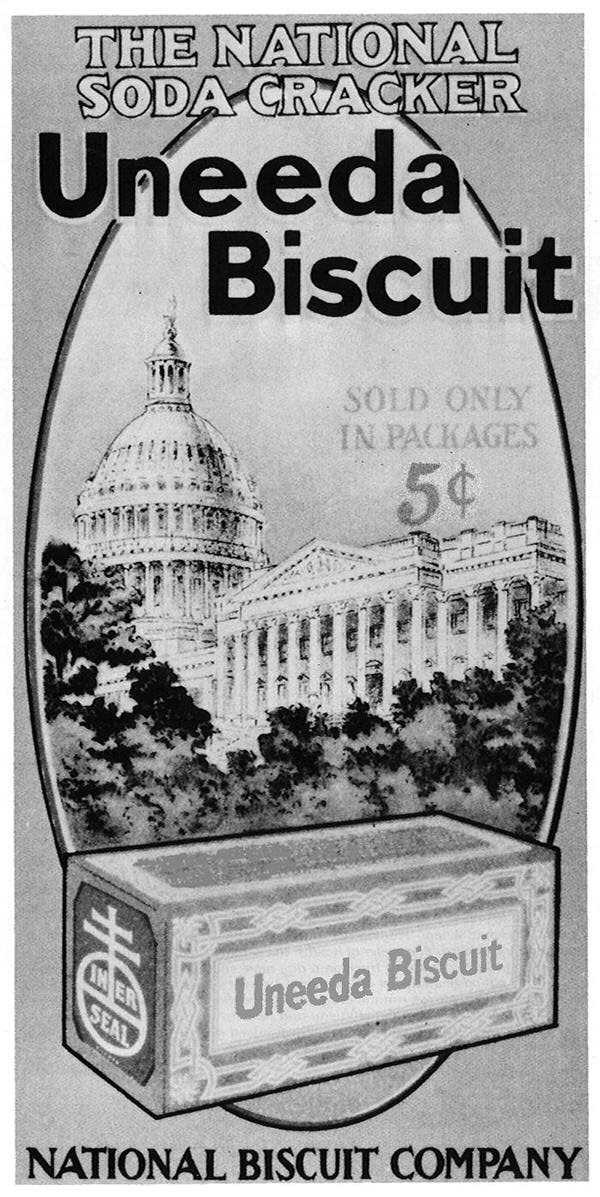

Here’s an example: In 1898, three regional companies—New York Biscuit, American Biscuit and Manufacturing, and the United States Baking Company—joined to form the National Biscuit Company. The directors of the new firm decided to embark upon a two-pronged strategy—centralize production through buying out competition and integrate forward to the customer. So after 1900, National Biscuit attempted to capture economies of scale through the consolidation of production facilities and increases in throughput. They also tried to develop specific brand names, like “Uneeda Biscuit,” and blitzed consumers with increased advertising. With this strategy, National Biscuit kept unit costs low and created major barriers to entry for new competitors, who were limited to a few firms structured like National Biscuit, but usually operating on a regional scale. Many industries had their version of National Biscuit by the early 20th century: U.S. Steel, American Tobacco, American Bell, and the International Paper Company.

Aluminum Becomes Cheap

So what does this all have to do with Alcoa? Well, at about the same time that the Sherman Act appeared and American businesses started to grow so rapidly, there were changes in the aluminum business. Charles Martin Hall, in Oberlin, Ohio, was experimenting in the woodshed of his kitchen and developed an inexpensive way to smelt aluminum. In 1888, he filed a patent for his discovery and organized the Pittsburgh Reduction Company, which in 1907 was renamed the Aluminum Company of America, later shortened to just Alcoa. Hall was initially excited about his breakthrough, until he learned that Paul Héroult of France had discovered the same thing at virtually the same point in history. Héroult got a French patent, but never really spun his aluminum process into a commercially viable endeavor.

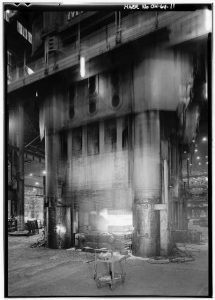

The use of an electric current is the best way to reduce aluminum oxide back to aluminum. However aluminum oxide is an insulator. The Hall-Héroult Process, as it is called, smelts aluminum metal by passing an electric current through a solution of aluminum oxide (obtained from a mineral called Bauxite) mixed with a substance called cryolite, which is sodium aluminum fluoride. The cryolite melts at a much lower temperature than aluminum oxide, and the melt is electrically conducting. In addition, aluminum oxide will dissolve in the molten cryolite, enabling electrical reduction of the aluminum oxide to metallic aluminum. After running the current through this solution, pure aluminum begins to form on the end of a graphite rod. Initially, this process made very small amounts of aluminum, but once larger pots and a steady source of electricity could be applied, this once very difficult task of smelting aluminum became commercially viable. [3]

Selling Aluminum

When the Washington Monument was capped with an aluminum pyramid in 1884, it was about $16 per pound—that’s nearly $400 per pound in today’s prices—but Hall’s process initially reduced that cost in half, and by 1900 his company could make aluminum for about 33 cents per pound. Aluminum very quickly evolved from an exotic metal to a lightweight material that had many potential functions. At first Alcoa sold mostly ingot and sheet aluminum, and soon moved “downstream” towards the consumer and made new goods. Teakettles and utensils, for example, became part of their lineup when they acquired utensil manufacturers. Aluminum’s non-corrosive properties allowed the company to sell sheeting and tubing as well. And by 1908, they were fabricating wire and moved into the utilities market. As the automobile market developed, aluminum was a natural fit because of its lightweight alloys.

Alcoa grew very rapidly: from 1900 to 1914, the company’s capital surged from $2.3 million to more than $90 million. During that time, the firm’s leaders, Arthur Vining Davis and Alfred Hunt, embarked upon a policy of rapid growth in order to achieve economies of scale. They built a massive facility to generate electricity at Niagara Falls and moved beyond Pittsburgh to build large smelting facilities in New York State, Tennessee, and Canada. In order to improve throughput, Alcoa acquired bauxite mines in Arkansas and built a refining plant in East St. Louis to create alumina (aluminum oxide), the material that the Hall-Héroult Process used in order to refine aluminum metal. World War I was particularly good for business, as Alcoa increased production from 109 million to 152 million pounds; wartime applications took up to 90 percent of the firm’s production. But government officials were wary, and in 1917 the War Industries Board accused the company of unfair practices when they charged a bit more for aluminum canteens than the market price. Scrutiny of Alcoa—and talk of antitrust proceedings—began to increase.[4]

The Antitrust Problem Starts

Part of the problem was that Alcoa was coming of age during the time that the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Clayton Act appeared in 1914. The FTC was created as an independent commission to enforce antitrust laws. It had five members who were elected to seven-year terms in order to isolate them from political influences. The FTC supposedly had broadly granted investigatory powers and could theoretically order businesses to stop a particular action if members thought the firm was acting in violation of antitrust laws. The Clayton Act shored up antitrust laws by making certain practices illegal. It did not allow contracts between firms that restricted firms from doing business with competitors, and it did not allow price discrimination in the effort to limit competition. For labor unions, the Clayton Act was important because it ruled that unions were not illegal combinations in the constraint of trade (remember that this is what the Sherman Antitrust Act was originally used to enforce). All this shoring up of antitrust agencies meant that Alcoa’s executives had a great deal to worry about as they grew their market share during World War I.

The Southern Aluminum Company, centered in Badin, North Carolina, and backed by French investment capital, attempted to compete with Alcoa in markets across the American South. This gambit failed—Alcoa was too strong by this point—and the company’s Board of Directors voted to sell all of their assets. In the era of American Big Business, this should have been a classic case of merger and acquisition, but Alcoa walked cautiously in this case. And although it bought the assets of Southern Aluminum Company in 1915, Alcoa asked for clearance from the FTC. This process was called “advance advice,” and it was one potential way for U.S. policymakers to regulate the growth of industrial firms.[5]

Nevertheless, Alcoa had become an effective monopoly. Arthur Varning Davis admitted as much when he testified before the War Industries Board in 1918. “I suppose it has always been our aim to foster this industry,” he told government officials. Alcoa considered itself to be the “father as well as the creator of this industry,” and in regards to competition, “it has always been our conception that the stability of price was the basis on which to build the industry.”[6]

Finding Markets for Aluminum

In the 1920s and 1930s, Alcoa began aggressively expanding its product line and aluminum became a commonplace metal in American industries and in the home. There were lightweight window frames, decorative railings, and all sorts of goods that took advantage of aluminum’s special properties. In products that needed to be light, for example, aluminum could replace iron or copper. The virtues of aluminum’s resistance to corrosion also became a selling point for many products. In 1928, an Alcoa ad bragged that “the transforming power of aluminum paint” could transform dingy industrial villages into modern towns.[7]

In 1930, Alcoa built the Aluminum Research Laboratory, in which the company enlisted full-time research scientists at New Kensington, Pennsylvania, to develop new alloys and products and to improve the smelting and refining process. The scientists there worked on plastics, stainless steel, nickel alloys, and magnesium. They not only worked on aluminum products for contemporary times, but also tried to anticipate alternative technologies that might replace aluminum. Basically, Alcoa paid very smart engineers and scientists to think of ways to reduce the cost and promote the use of aluminum. It was about as close to “pure” research as one could find in the private sector, and Alcoa’s commanding market share shielded the Aluminum Research Laboratory’s staff from the pressure to develop new products immediately.

The Federal Government Acts

But even though it fostered a corporate culture of size and stability, Alcoa’s dominance over aluminum markets created problems for the firm. In 1938, Alcoa celebrated its 50th anniversary while preparing a defense against an antitrust lawsuit. The Justice Department wanted to “create substantial competition in the industry by rearranging the plants and properties of the Aluminum Company and its subsidiaries under separate and independent corporations.” During the New Deal Era of the 1930s, American policymakers became more and more concerned that large industrial corporations were dominating the economic landscape. Even though Alcoa was not rapacious in dealing with its competitors, the Department of Justice argued that its size and market share alone made it an appropriate target for antitrust proceedings. The case lasted 176 days, Alcoa spent $2 million defending itself, and, although the case was undecided when Japan bombed Pearl Harbor in late 1941, it continued during the war. One of Alcoa’s executives complained, “If we are a monopoly, it is not of our choosing.” Despite the lawsuit, Alcoa became heavily involved in the war effort, producing 3.5 billion pounds of aluminum that went toward the manufacture of 304,000 airplanes. Many of these airplanes used alloys that Alcoa had developed in their laboratories.[8]

Nonetheless, the government still pursued the case and in 1945, on appeal, a Circuit Court justice with the greatest legal name of all time, Learned Hand, gave the verdict. He argued that there was no such thing as a “good monopoly” and that there was no way that any company could achieve a monopoly share simply through efficiency and good business practice. So, in the postwar years, Alcoa saw many of its facilities sold for pennies on the dollar to its competitors, Reynolds Aluminum and Kaiser Aluminum. In 1950, the Court set Alcoa’s market share at 50.85%, which, at least in their eyes, put them in a more competitive relationship with Reynolds (30.94%) and Kaiser (18.2%).[9]

A Post-Alcoa World

This application of the Sherman Antitrust Act really had a major impact on American business. If Alcoa could be broken up because of its market share alone, then other firms might be wary of achieving economies of scale and improving throughput in order to repeat Alcoa’s success. In the postwar era, many large industrial firms chose to grow in a completely different fashion. Whereas Alcoa sought to gain control over the production of a single material, many postwar firms sought to grow in completely different ways.[10]

For example, take the story of Textron, which began as a textile business. Its owner, Royal Little, was good at making textiles, but after the Second World War, the textile industry was a volatile one that suffered immensely from market swings. Little knew that he wasn’t going to dominate the textile industry; even if he did, in the post-Alcoa antitrust environment, the Supreme Court would probably come after him. Beginning in 1954, Little devised a new strategy for Textron. He began acquiring small- and intermediate-sized firms at a rate of about two per month, and he was borrowing heavily to do it. In 1956 alone, Textron purchased firms that made cement, aluminum, bagging, plywood, leather, and Hawaiian cruise ships. Little also began to sell off Textron’s unprofitable divisions—many of which were in textiles—and by 1963 he had sold the last of Textron’s textile plants. By 1968, Little was in semi-retirement and Textron had revenues of $1.7 billion and earnings of $76 million. It was number 49 on Fortune Magazine’s list of the 500 largest companies—even ahead of Alcoa, which had dropped to number 56!

The other example of the move away from Alcoa’s growth strategy is the story of International Telephone and Telegraph, or ITT. This firm was founded as a small telephone company in Puerto Rico and Cuba in the 1920s, and it was moderately successful when Harold Geneen took it over in 1959. After that point, ITT began to expand rapidly. It acquired Avis in 1965, Cleveland Motels in 1967, and Pennsylvania Glass and Sand, Continental Baking, and Sheraton Hotels, all in 1968. You can see where this is headed. But ITT was even more expansionist than Textron: By 1970, ITT had 331 subsidiaries and 708 subdivisions. It operated in 70 countries, had 400,000 employees, and sales of $5.5 billion—and was ranked number 21 on that same 1968 Fortune 500 list! Both ITT and Textron proved to the business world that you could get big fast—and you didn’t even have to be particularly innovative in what you produced. With some creative accounting, gutsy acquisitions, and stock swaps, Textron and ITT became giants over the course of a decade. And they did it with a completely different strategy than Alcoa. Rather than make one thing exceptionally well, conglomerates sought to make profits across many markets and avoid antitrust problems altogether.

The Beer Can Barons

Don’t weep too much for Alcoa in the postwar era. From 1946 to 1958, its gross revenues tripled up to $869 million. One writer in 1955 called it Alcoa’s “splendid retreat” from monopoly. By 1952, moreover, aluminum had passed copper in civilian consumption and now is second only to iron. In 1977, the NASA’s Space Shuttle Enterprise, covered by an aluminum alloy, made its maiden voyage on top of a specially modified Boeing 747 jetliner, also covered with an aluminum alloy. But in addition to conquering sky and space, aluminum became integrated into daily life through more humble means. In new markets, like beer and soft drink containers, aluminum went from less than two percent of the market in 1964 to 95 percent in 1986.

Legacy

But the question remains, is a commanding market share indication of a troubled industry, or can a company be too good at its business? That’s why Alcoa’s story is important to consider. The bottom line is that Alcoa did popularize the use of aluminum among American consumers, made the company’s products cheaper, and contributed to the growth of the industrial economy of the 20th century—particularly in vital sectors like the airline industry. But as the name of Alcoa became synonymous with the production of aluminum, it also became notorious among antitrust circles. In the end, the federal government decided that such a large company was naturally incompatible with their view of modern industrial capitalism. The breakup of Alcoa hardly destroyed the company, but it did send a larger message out to firms like Alcoa that might have forged ahead with the large-scale production of their materials. In the postwar American economy, companies still grew large, but often did so with a completely different strategy than Alcoa had employed in its first half-century of growth. So not only did the emergence of Alcoa help structure the American economy of the early 20th century—quite literally in the case of aluminum construction products—but its breakup helped structure the ways in which businesses grew in the late 20th century in the United States.

Discussion Questions

- Can you think of any other materials that are currently considered luxury products, but might revolutionize everyday life if they became more widely available?

- Do you agree with Alcoa’s early strategy of engaging both in the mass production of aluminum and developing new markets for aluminum products? Were company officials seeding their own destruction by trying to do everything with aluminum?

- Do you think that antitrust actions against Alcoa helped or hindered the American economy in the long run?

- Do you think that there is a need for antitrust legislation today? Does the federal government need to break up large companies in the interest of competitiveness?

Key Terms

antitrust

monopoly

economies of scale

throughput

horizontal integration

Sherman Antitrust Act

Hall-Héroult Process

Further Reading

Carr, Charles. ALCOA: An American Enterprise. New York: Rinehart & Company, 1952. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/236816.

Peck, Merton J., ed. The World Aluminum Industry in a Changing Energy Era. Washington, DC: Resources for the Future, 1988. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/756989950.

Stuckey, John. Vertical Integration and Joint Ventures in the Aluminum Industry. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press, 1983. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/924980139.

Author Biography

Sean Adams is the Hyatt and Cici Brown Professor of History at the University of Florida in Gainesville, where he teaches courses in the history of American capitalism, the global history of energy and 19th century U.S. history. His most recent book on energy transitions and home heating is entitled Home Fires: How Americans Kept Warm in the 19th Century (Johns Hopkins, 2014) and it explores the roots of America’s fossil fuel dependency during the Industrial Revolution. He is also the author of Old Dominion, Industrial Commonwealth: Coal, Politics, and Economy in Antebellum America and a three-volume anthology entitled The American Coal Industry, 1789–1902, along with numerous articles, reviews, and book chapters.

- George J. Binczewski, "The Point of a Monument: A History of the Aluminum Cap of the Washington Monument," JOM 7 (1995): 20–25, http://www.tms.org/pubs/journals/jom/9511/binczewski-9511.html. ↵

- Naomi Lameroux, The Great Merger Movement in American Business, 1895–1904 (New York: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1988), 164–66, http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1157046408. ↵

- "Hall Process: Production and Commercialization of Aluminum," National Historic Chemical Landmarks, American Chemical Society, http://www.acs.org/content/acs/en/education/whatischemistry/landmarks/aluminumprocess.html. ↵

- Alfred Chandler, Scale and Scope: The Dynamics of Industrial Capitalism (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press, 2009), 122–24, http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1041153323. ↵

- Mira Wilkins, The History of Foreign Investment in the United States, 1914–1945 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press, 2009), 32–33, http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1041152151. ↵

- George David Smith, From Monopoly to Competition: The Transformations of Alcoa, 1888–1986 (New York: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1988), 112–13, http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/908388984. ↵

- Roland Marchand, Advertising the American Dream: Making Way for Modernity, 1920–1940 (Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 1985), 262, http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/35117815. ↵

- Smith, From Monopoly to Competition, 191–202. ↵

- Smith, 242. ↵

- A. Tony Freyer, Antitrust and Global Capitalism, 1930–2004 (New York: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2006), 32–40, http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/286424757. ↵

Feedback/Errata