Polymers: Fantastic Plastics in Postwar America

Marsha Bryant

“Plastic is, all told, a spectacle to be deciphered: the very spectacle of its end-products. At the sight of each terminal form (suitcase, brush, car-body, toy, fabric, tube, basin or paper), the mind does not cease from considering the original matter as an enigma.” —Roland Barthes[1]

Abstract

This chapter explores how social and cultural systems such as language, gender, aesthetics, home design, and advertising shape the ways we perceive the intrinsic physical properties of materials. Because of their ubiquity in consumer culture, plastics prove especially interesting in these contexts. Even the word plastic bears multiple meanings that shape our complicated relationship with this versatile material. The story of Tupperware’s invention, distribution, and marketing offers a case study of how materials acquire meanings that shape the ways we publicize and use them. A new polyethylene product in postwar America, the Tupperware bowl became an enduring museum object as well as a household icon.

Introduction

What’s in a name? Shakespeare asked in Romeo and Juliet. With plastics, a synthetic material made from polymers, the answer is complicated. Wherever you’re reading this, you’re likely within reaching distance of at least one plastic product: a cellphone or laptop case, a water bottle, a credit card, a pen, a trash receptacle. Plastics are all around us, every day. Our relationships with plastics can be as richly diverse as the shapes and colors these malleable materials can assume. Plastics also shape our material relations through brand names such as Fiberfil, Mylar, Plexiglas, Teflon, and Tupperware. Even the word plastic comes preloaded with contradictory meanings.

Plastics and the Power of Naming

Untangling these scientific and cultural meanings reveals our vexed relationship with plastics. The word’s Greek origins link plastic to plassein (to mold), a dynamic process that makes plastics attractive to manufacturers. Easily shaped through heat and other applications of force, plastics are pliable, ductile, flexible. This technical meaning highlights the material’s incredible capacity to transform. In the biological sciences, plastic means adaptable to environmental changes. Plastic also has aesthetic meanings: three-dimensional modeling, or giving the effect of three dimensions. A more plastic model or actor offers more creative possibilities for the canvas or camera. The word can mean an expanded scope for creativity; a medium such as paint or stone can become plastic in an artist’s hands. All of these positive meanings make plastic products attractive to manufacturers and advertisers.

Yet there’s a flip side to plastics embedded the same word: plassein also means to feign. In social relations, plastic can mean superficial or false. A plastic performer is someone you’d like to see on stage. But a plastic person is someone you’d likely consider phony and avoid. These negative social meanings also affect the material’s marketability, even as plastic products continue to fill stores and household shelves. A manufacturer may like plastics because they are cheap to produce. But a consumer may reject a product that looks cheap or gaudy. No wonder we have a love-hate relationship with this material! British punk artist Poly Styrene distilled the tension of plastic’s cultural meanings in her stage name. In the late 1970s the punk aesthetic prompted disaffected youth to thumb their studded noses at a British establishment that offered them “no future,” as the Sex Pistols proclaimed in their punk anthem “God Save the Queen.” Poly Styrene created a rebellious identity for young women through her unconventional attire and anti-commercial lyrics, sporting vinyl accessories and shout-singing edgy songs like “Plastic Bag” with her band, X-Ray Spex. In riotous fashion, Poly Styrene embodied and rejected the artificial culture she saw all around her. She took the name of a common plastic and made it a punk icon.

Seeing Plastics through New Eyes

Responding to postwar mass culture in the late 1950s, French literary and cultural critic Roland Barthes included an essay on plastics in his influential book Mythologies (1958). Originally published in a literary journal, the book’s analyses ventured boldly beyond Barthes’s traditional academic field. He assessed how household products and new technologies transformed everyday life in ways he considered mythic: they gave contemporary society its primary means of cultural coherence, functioning as a secular religion. Barthes saw in modern plastics the fulfillment of an ancient dream: alchemy, the transmutation of matter. Enchanted by the names of consumer plastics, he imagined polystyrene, polyvinyl, and polyethylene as Greek shepherds in a world of gods and monsters. Instead of viewing plastics through the lenses of science, engineering, and technology, Barthes viewed them through language, literature, and philosophy. The material was magical for Barthes because it was alive with possibility: “More than a substance, plastic is the very idea of its infinite transformation.”[2] Sounding as much like an ad man as a philosopher, Barthes pitched plastics as nothing short of miraculous.

How can we see this material through new eyes? How has plastic been a fantastic material for inventors, design critics, and advertisers? If we stretch our thinking across academic fields, we can draw from key historical encounters with modern plastics and imagine new possibilities. Earl Tupper, inventor of Tupperware products, saw such promise in postwar polyethylene that he called it Poly-T: Material of the Future. At the corporation’s Florida headquarters, legendary businesswoman Brownie Wise put raw polyethylene pellets in “Poly Pond”—sprinkling its water on successful saleswomen to give them “Tupper Magic.”[3] Perceiving polyethylene with as much imagination as practicality, Tupper and Wise translated their visions into patent applications and successful sales strategies, respectively.

For plastics to fulfill their potential, Robert Friedel wrote in Pioneer Plastic (1983), there should ultimately be a “function for every plastic and a plastic for every function.”[4] Given plastic’s many types and possibilities, this material will be with us for a long time; polyethylene alone reached a global supply of 100 metric tons in 2014.[5] Like other thermoplastics, it can assume new shapes and consistencies when heated, melted, and injected into a mold. The polyethylene that Tupper encountered as a plastics sample maker was an industrial waste product—opaque, greasy, clumpy black slag. With these unappealing properties, polyethylene seemed unsuitable for the household market. Tupper would refine polyethylene into a translucent plastic that could take on a range of colors, yielding what journalist Bob Kealing calls “a polished, waxy, upscale plastic.”[6] You might say Tupper transformed polyethylene from slag to swag.

How could something as simple as polyethylene become so compelling at the dawn of the space age? How did this material meet people’s needs, and how did it change society? Why did design experts love plastics? Cultural historian Alison Clarke explains that Tupperware products mattered because they were “at once mundane and extraordinary.”[7] As we shall see, Tupper’s ingenious refinement of polyethylene and Wise’s sales acumen made productive use of plastic’s versatility.

How the Tupperware Brand Came to Be

Three key moments in American history shaped the fortunes of Tupperware products’ inventor, material (polyethylene), and master promoter: the Great Depression (1929–1940), World War II (1939–1945), and the postwar boom (1946–1960). The first gave Earl Tupper his deeply ingrained values of thrift, resourcefulness, and positive thinking. The second gave polyethylene (and other plastics) new applications in the war industry. And the third gave Brownie Wise an opportune moment to revolutionize direct sales in American homes.

The Homemade Inventor, Earl Tupper

Earl Silas Tupper came of age during the Great Depression, sustained and seasoned by kinship, manual labor, and relentless self-improvement. Born in New Hampshire in 1907 to a farming family, Tupper grew up in a Massachusetts household that often struggled to make ends meet. Ambitious and enterprising since boyhood, Tupper tinkered with ways to improve farm chores. At age 10 he took his parents’ produce door-to-door to boost sales. Tupper finished his formal education with high school in 1925, working at the small plant nursery his parents had started after they abandoned farming. He also started his first business as a tree surgeon and landscaper. A self-taught inventor and domestic entrepreneur, Tupper fashioned a wide-ranging personal curriculum that included taking correspondence classes, visiting libraries and trade fairs, reading widely, and writing regularly. His sketchbook and invention journal had plans ranging from egg peeling clamps to a giant theme park he named Cosmopolita World.[8]

While he kept his eye on the future, Tupper drew inspiration from legendary thinkers such as Leonardo Da Vinci, Thomas Jefferson, and Thomas Edison. In his notebook, he wrote: “An inventive, intuitive, enthusiastic and trained mind continues to experiment, study, search and develop along an entire line of human endeavor.”[9] Tupper drew from humanities, science, technology, and business to make history as a plastics inventor. We can see his continuing influence on American innovation at the Smithsonian Institution. The National Museum of American History houses his papers, and the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama houses the Earl S. Tupper Research and Conference Center to foster research and development across the sciences.

Earl Tupper’s Homemade Curriculum for Innovation

- Technology

- Literature

- Popular magazines (including American Home, Popular Mechanics, Literary Guild)

- Writing (personal journals and notebooks)

- Advertising (correspondence school)

- Industry experience (Doyle Factory, DuPont)

- Following business trends (trade shows, the New York World’s Fair)

- Consulting with women about product designs (family, neighbors, coworkers)

The Great Depression and Tupper’s farming background played formative roles in how he conceived his breakthrough invention. In an economy of scarcity, thrift and wastefulness loom large; survival depends on making the best uses of what you have. Observing the women working all around him, the young Tupper resolved to make domestic life easier—from cleaning chickens to washing dishes. As Clarke explains, he believed that thrifty provisioning and modern technology could sustain home and society; by contrast, extravagant consumption wasted time and materials. This ideology shaped his early promotions about Tupperware products paying for themselves.[10] Though not cheaply priced, the product’s durability and superior seal preserved pantry staples and saved leftovers, stretching household budgets and reducing waste. (The Tupperware Ladies pitched this feature with a new word: plan-overs.)

Material Transformations

The plastic material that Tupper would transform for the household market—polyethylene slag—was an industrial waste product he encountered after his tree surgery business failed. In 1937 he moved with his wife and sons to try his fortunes at the Doyle Works, a plastics factory affiliated with DuPont. Through such small operations, DuPont employed amateur sample makers to further plastics research and development. This mutually advantageous arrangement gave Tupper access to scrap material, allowing him to take it home and invent prototypes. When polyethylene production took off in the United States in 1943, the material proved primarily important for wartime uses such as insulation, container linings, cable coatings, gaskets, and tubing. Tupper would domesticate polyethylene, viewing the material as a World War II veteran now ready for civilian tasks.[11]

Working to overcome the material’s limitations, Tupper wanted to produce a plastic more durable than molded transparent styrene. He wanted something that could flex without breaking, something that could stand up to lemon juice and vinegar, something physically appealing to homemakers.[12] In fact, women were integral to Tupper’s design breakthrough. He often interviewed female relatives, neighbors, and coworkers to foster ideas for his inventions: a dish rack with drains, better knitting needles, eyebrow dye shields. He had a capable and dedicated partner in his wife, Marie. She would give him tools to improve his sample making, and he would give her his new inventions.[13]

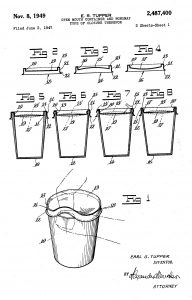

After Tupper’s initial failures with the injection molding machines, he took samples home and asked his son Myles to put them in boiling water and remove each at a specified time. Eventually Tupper found the right balance of pressure and temperature, so the polyethylene flowed into various shapes of the desired thickness. He also fashioned a system for dying his translucent containers in pastel colors. But he needed something else: the right lid. As Kealing points out, many American women had relied on tin foil or shower caps to cover their leftovers. Tupper turned to an everyday object for inspiration: paint cans. He fashioned a flexible polyethylene lid that allowed an airtight seal, protected and preserved food, prevented spills. With a simple hand movement, you could manipulate the seal to expel air. He founded the Earl S. Tupper Company in 1939, which became the Tupper Corporation in 1947. That same year, an article in Time magazine hailed the inventor for “a process which overcomes the material’s tendency to split, makes it tough enough to withstand almost anything except knife cuts and near-boiling water.”[14] The toughness of Tupperware products makes a comic appearance in the film Napoleon Dynamite (2004) when salesman Uncle Rico urges a client to tear the product with his bare hands—an impossible task.

Activity: Explore the Museum of Modern Art Website

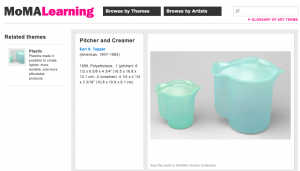

Navigate to the MoMA Learning website and search for “tupperware.” How does the product’s display as a museum object change your perception of its material?

Click Browse by Theme and enter plastic. Click the Theme box Plastic at the top left, and check out the resources. If you click Tools & Tips, you’ll find worksheets on design and environmental issues.

On the same page under Multimedia, you’ll find a brief video on plastics produced in 1944 for the Young America series. How would you promote plastics to your own generation?

Polyethylene as Everyday Art Object

In 1948, the Tupper Corporation’s tea set made the Modern Plastics Encyclopedia as an ideal incarnation of domestic polyethylene. If you think about it, plastic seems an unlikely material for this purpose. We don’t usually count plastics with traditional wedding gifts and family treasures: silver, china, and crystal. Yet we find the Tupperware pitcher and creamer in the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), along with Tupper’s tumblers, bowls, and “Ice-Tups” (his ingenious popsicle molds). MoMA curators included Tupperware products in “Good Design” exhibitions in the 1950s, as well as the 2011 exhibition “What was Good Design? MoMA’s Message, 1944–1956.”

Key Concept: Modernist Aesthetics 101

“No ideas but in things.” —William Carlos Williams, physician and poet

- Form over function

- Autonomy of objects

- Objects can transcend the ordinary

- Clean lines, geometric designs

- Classical restraint over Romantic excess

- Authenticity

- Directness

- Experimental form

“Not Ideas about the Thing, but the Thing Itself.” —Wallace Stevens, business executive and poet

Just as Tupper made plastic respectable for middle-class Americans, he turned polyethylene into an artistic medium. In 1947, an editor for House Beautiful enthused that Tupperware bowls “have a profile as good as a piece of sculpture,” declaring that the product satisfies “our aesthetic craving to handle, feel and study beautiful things.” Tupper’s timing was good because his product fit the aesthetics of modernism, an established style in museums, publishing, and universities. Tupperware products redeemed common plastic through a superior form that fused beauty with utility. As Clarke explains, they fulfilled modernism’s “ideal of a tasteful, restrained, and mass-produced artifact, free of inauthentic decoration and gratuitous ornament.”[15] The product brought class to “mass.” And above all, it was true to its material. You can see the modernist heritage of Tupperware products in this contemporary video ad for the Tupperware Breakfast Maker. Note how the camera highlights the sleek, colorful design, bringing plastic to life.

How Tupperware Became an American Icon

Tupper’s timing was also fortuitous because of postwar changes in American home and family life—the third historical context that shaped his product’s fortunes. New social spaces—suburbs—refashioned family relations for many Americans, prompting them to move away from the city (and their extended families). As historian Elaine Tyler May points out, “the legendary white middle-class family of the 1950s, located in the suburbs, complete with appliances, station wagons, backyard barbecues, and tricycles scattered on the sidewalks, represented something new.”[16] These postwar couples in their ranch houses were suburban pioneers. Like their mythic counterparts Ward and June Cleaver on television, the Breadwinner and Housewife roles created a gendered division of labor outside and inside the home. Breadwinner donned his gray flannel suit for his morning commute to the office, conforming to a role that social analyst William Whyte termed the Organization Man. Housewife provisioned her home and performed the three C’s: cleaning, cooking, and childrearing. She conformed to the new standard of professionalized homemaking, and she was an ideal customer for Tupper’s ingenious products. May points out that housewives wielded considerable buying power in postwar America: “In the five years after World War II, consumer spending increased 60%, but the amount spent on household furnishings and appliances rose 240%.”[17] But even so, Tupperware products weren’t flying off the shelves.

The Savvy Saleswoman, Brownie Wise

Brownie Wise changed Tupper’s fortunes when he noticed her unusually large orders coming out of Detroit in 1949. A door-to-door seller for Stanley Home Products, Wise had formed her own side business to promote Tupperware products with “Poly-T Parties.” She found the Wonder Bowl distinctive enough to sell, but she fumbled with the seal—until she realized that “you had to burp it just like a baby.”[18] And with that personal analogy Brownie Wise made Earl Tupper’s product come alive in American homes. A television commercial from the 1950s shows a Tupperware party; note the female voiceover and the hands-on demonstrations.

Wise did not see Tupperware products as museum objects to be looked at; they were beautiful things to touch and handle. Her early sales plan insisted that a good “visual demonstration” is the “means of creating a desire for the product.”[19] Wise knew how to handle her material, too. In her hands, Tupperware products burped up sales. In her hands, Liquid-filled Wonder Bowls flew across American living rooms, astonishing housewives with that airtight seal. In her hands, the Tupperware Home Parties Division made Tupperware a household word. Tupper made her general sales manager in 1951, and she became a vice president.

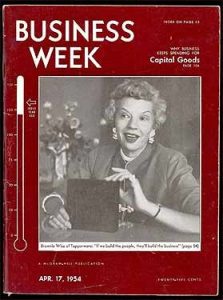

The first woman to appear on the cover of Business Week (April 1954), Wise transformed materials marketing as dramatically as Tupper had transformed polyethylene. With even less formal education than Tupper, Wise overcame financial hardship with resourcefulness and determination. A divorced single mother in Detroit, she turned to sales to supplement her low-wage secretarial job and pay her son’s medical bills. Her sales experience helped Wise hone her techniques for selling Tupperware products and recruiting dealers. As Kealing explains, she turned away from the “hard sell” for a softer approach that stressed “the social and emotional aspects” of the transaction.[20] Wise praised her Detroit dealers for stand-out parties and sales figures in her upbeat newsletter, the Go-Getter; it eventually became the Tupperware Sparks publication for a national sales force. Wise wrote guidelines for successful demonstrations—and for sizing up potential Tupperware Ladies. She also published her autobiography, Best Wishes, Brownie Wise (1957), reprinted 40 years later to motivate a global sales force.

Wise convinced Tupper to fundamentally change his marketing strategy. Taking his product off the shelves and out of the stores, her business plan put more Tupperware products into more women’s hands. Her Tupperware Home Parties Division moved to Florida in 1950. And the woman once told that women couldn’t advance at Stanley became a business celebrity and inspirational figure. At her Jubilee conventions in Orlando, Wise offered Tupperware Ladies fur coats, jewelry and other fine things as sales incentives. You can see Wise work her sales magic in Laurie Kahn-Levitt’s film Tupperware! (2004), aired on PBS. Though the product bore Tupper’s name, Brownie Wise became the face of the company—a factor in Tupper’s decision to fire her in 1958. But Wise proved pivotal to making Tupperware Brands Corporation the successful enterprise it remains today. She also gave postwar American housewives paid work within the home that was socially acceptable. Part housewife, part hostess, part businesswoman, the Tupperware Lady straddled the era’s social categories, crossing geographic, racial, and class boundaries. There were also husband-and-wife teams who worked as Tupperware dealers inside and outside the home.

American Advertising and Materials Marketing

The postwar boom and dream kitchen ushered in new ways of marketing household products as advertisers courted American housewives. Like Mad Men’s Don Draper, they competed relentlessly for women’s attention. How could they make their client’s product stand out from the other brands? Tupper had taken an advertising correspondence course, and he kept in touch with his ad executives. He wrote to one that “a product is not exactly what you make it in the factory, but it is also and more so what you make it when you sell it.”[21] A successful advertisement brings together the manufacturer, product, and consumer in a dynamic relationship. Revisiting milestones in American advertising can help us understand the many ways consumers connect with products and their materials. Juliann Sivulka explains that postwar advertisers began to move away from hard-selling product features, drawing from psychology “to build a product image or brand personality.”[22] The three classic campaigns I discuss here take different proximities to the product, emphasizing in turn the consumer, the product itself, and the desired image.

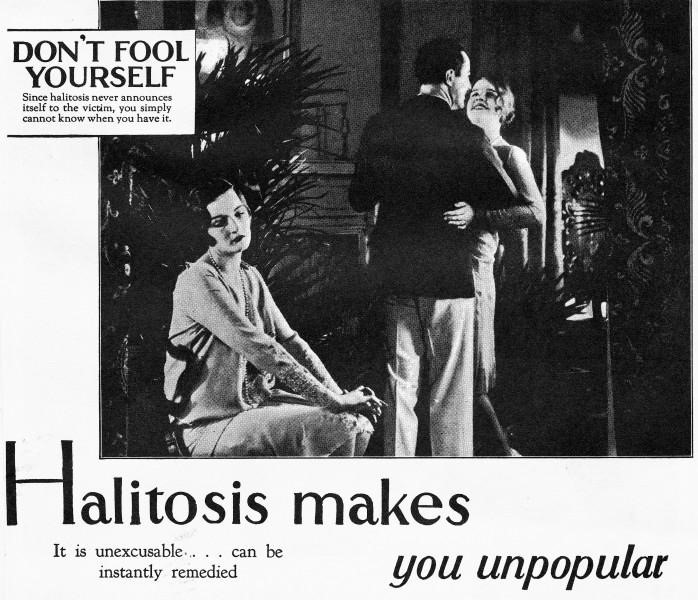

Listerine and Selling the Need

The first shows Gerard Lambert’s strategy of selling the need. His Listerine campaign made the medical term for bad breath—halitosis—a household word. It all started in the late 19th century with a surgical antiseptic that physician Joseph Lister formulated in England. In 1879, Joseph Lawrence made a milder version in the United States, naming it after Lister and promoting it as an all-purpose antiseptic. First successful with dentists, Listerine entered the mass market in the 1920s. By then the Lambert Pharmaceutical Company had acquired the product, and Gerard Lambert was seeking greater profits. Learning about halitosis from a company chemist, Lambert seized upon the word as a way to get Listerine into more mouths.[23] Halitosis sounded as unseemly as it was. Making people aware of it would make them want to get rid of it.

We can see how the pitch worked in this top half of a 1928 Listerine ad. If you take a close look, you’ll see how efficiently the ad’s words and image distill its claims and implications:

- The textbox at the top left makes no one immune. Halitosis strikes at any moment!

- In the image, décor and attire show that even respectable people suffer from halitosis.

- The afflicted woman in the corner stands out by sitting out this dance. She looks exposed and uncomfortable, unlike the smiling woman dancing with her partner.

- By implication, halitosis kills any chance at romance.

- The copy beneath the image makes us the culprit for halitosis. With Listerine so readily available, bad breath becomes an unforgivable faux pas.

In his bestselling book Advertising the American Dream (1985), historian Roland Marchand explains that such ads play on “the Parable of the First Impression”—a powerful theme in ads from the early 20th century.[24] (210). Selling the need to avoid embarrassment through the invisible menace of halitosis, Lambert’s Listerine campaign made antiseptic mouthwash the antidote to unpopularity.

Anacin and the U.S.P.

The second advertising milestone powered Rosser Reeves’s Hard Sell technique—the Unique Selling Proposition (U.S.P.). A contemporary of Tupper’s, Reeves did his most influential work with the Ted Bates ad agency in New York in the 1940s and 1950s. (He had first worked as a journalist.) In his bestselling book Reality in Advertising (1961), Reeves distinguished the U.S.P. from other strategies as an appeal to the consumer’s reason. He believed that a successful ad is efficient; it zeroes in on a precise claim about the product and avoids any distractions. Moreover, a successful ad avoids puffery and fantasy, grounding appeals in the product and reality.

We can see these strategies at work in Reeves’s famous Anacin commercial that featured an animation of a headache; look for it 35 seconds into this video from 1958.

Invoking the medical profession to enhance credibility, this Anacin ad zooms in on the headache and brings it to life. Like the pounding hammer in the middle panel, Reeves’s ad hits the reader in the head with his U.S.P.—fast. The repetition links the U.S.P. with other things that come in threes: e.g., “three out of four doctors recommend”; Anacin has three pain relievers; it relieves all three headache symptoms. The ad distinguishes its product from competitors’ and offers a specific benefit: Anacin will stop your headache fast, Fast, FAST. Sivulka points to contemporaneous U.S.P. ads that also proved effective: Certs breath mints with a magic drop of Retsyn; Colgate cleans your breath while it cleans your teeth.[25]

Hathaway and Branding

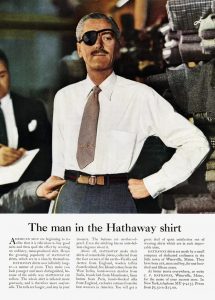

The third advertising milestone, David Ogilvy’s concept of branding, emphasizes the consumer’s desires as much as the product itself. Reeves saw branding this way: “To put it bluntly, the U.S.P. is the philosophy of a claim, and the brand is the philosophy of a feeling.”[26] But there was nothing blunt about Ogilvy’s creative approach to advertising:

Products, like people, have personalities, and they can make or break them in the marketplace. The personality of a product is an amalgam of many things—its name, its packaging, its price, the style of its advertising, and, above all, the nature of the product itself.[27]

Ogilvy took the idea of products and personality beyond personified objects (the “Tupperware burp”) and corporate personas (Betty Crocker, Uncle Ben). Ogilvy had sold cooking stoves door-to-door in England before moving to the United States in 1938. A decade later, he started a New York ad agency. Ogilvy became legendary in American advertising through his successful campaigns and his bestselling book Confessions of an Advertising Man (1963). He is the historical inspiration for the character Don Draper on Mad Men.

Ogilvy’s campaign for Hathaway also became legend. Drawing on the principle that consumers are less interested in the product per se than the image they buy with it, this ad creates a compelling character: “the man in the Hathaway shirt.” No conformist Organization Man in a gray flannel suit, this man was singular and sophisticated. He wore an eye patch. He could sail, paint, fence, ride horses, and play the oboe. A model of cultural refinement, he traveled the world. The man in the Hathaway shirt embodied the brand’s new personality. Launched in 1951, this campaign initially ran exclusively in The New Yorker.[28]

The Hathaway man’s descendants appear in contemporary ads for Dos Equis beer (The Most Interesting Man in the World) and Old Spice deodorant (The Old Spice Guy who smells like a man). But advertising was never strictly a man’s world. Ogilvy’s campaign succeeded in part because its international man of mystery appealed to women as well as men; after all, women were the primary shoppers in postwar America. Sivulka and other cultural historians have now turned their attention to women who work in advertising. Where would Don Draper be without Peggy Olson?

Conclusions: Tupperware and the Future of Plastics

Revisiting vintage promotional materials for Tupperware products reveals social and cultural meanings this iconic plastic conveyed to middle-class housewives in the 1950s–1970s. It also prompts us to think about how plastic’s properties might appeal to specific demographics in contemporary society. In this catalog cover from 1958, for example, Joe Steinmetz’s photograph places the woman in two key contexts: the family circle and the museum gallery. In the first, her provisioning enables the genial gathering we see in the background. Framed between glass shelves, just right of center, her husband smiles as he holds his Tupperware mug (Tupperware products also appear on the table). Mother is the central figure, arranging her Tupperware collection in a beautiful display that resembles a museum’s—the second context. She smiles at her Tupperware “family” as she would at the family seated behind her. Sleek, colorful, and modern, her Tupperware products have brought harmony to her kitchen and home. Everything is orderly; nothing is out of place.

The American postwar dream kitchen gleamed with shiny metal appliances, polished wood cabinets, and colorful linoleum floors. But plastics also transformed this vital space. A fantastic polymer, plastics can take on pretty much any shape and color we can imagine. Brownie Wise marveled at “the tremendous imagination it took” for Earl Tupper to change black polyethylene slag into his signature products.[29] More recently, Tupperware Brands Corporation has designed UltraPro Ovenware products that “can be used in temperatures up to 482° F/250° C and as low as -13° F/-25° C.”[30] The new copolymer ethylene-tetra-fluoro-ethylene (ETFE) has transformed the roof of the Minnesota Vikings’ football stadium, letting in light with lightweight transparency—and costing less than glass. This material also formed the dramatic bubble façade of the Water Cube venue for the 2008 Beijing Olympics. Where will plastics go next? Your generation will create imaginative designs for improved and future products, inventing new brand names for this fantastically versatile material.

Tupperware Milestones in Popular Culture

- 1974. All in the Family television series. Edith Bunker hosts her first Tupperware Party. (Season 5, episode 8)

- 1986. Tupper Ware Remix Party, a futuristic synthwave dance band, forms in Toronto, Canada.

- 1995. Seinfeld television series. Kramer tries to retrieve his Tupperware container from a homeless man. (Season 6, episode 15).

- 2004. Napoleon Dynamite film. Uncle Rico tests Tupperware’s toughness with a client, and Kip tests it with a van.

- 2015. American Horror Story television series airs “The Tupperware Massacre” episode. (Season 4, episode 9).

- 2015: Hollywood film about Brownie Wise goes into production

Discussion Questions

- Get your hands on a piece of Tupperware. What properties do you notice?

- Before Tupperware hit the market, most Americans stored their food in glass. Why is polyethylene a better material for this purpose?

- Which household appliance do you think most shaped the fortunes of Tupperware? Why?

- In postwar America, common thinking held that married women should spend most of their time in the home—especially if they were mothers. How did Brownie Wise make it socially acceptable for such women to sell Tupperware?

- Watch this video “Tupperware Celebrates World Water Day 2013.” What are the environmental impacts of plastic products? How might they contribute to sustainability?

- If you were to put your name on a plastic product, what would it be? Which kind of plastic do you think would be ideal for your purpose?

Key Terms

modernism

plastics

polyethylene

polymers

polystyrene

polyvinyl

thermoplastics

Author Biography

Marsha Bryant researches and writes about modernist studies, visual culture, women’s writing, popular culture, and pedagogy. She is Professor of English & Distinguished Teaching Scholar at the University of Florida, where her most popular courses include modern poetry surveys, Desperate Domesticity: the American 1950s, and PostPunk Cultures: The British 1980s. Her recent essays have appeared in The Massachusetts Review (about Walt Whitman and beer culture), Feminist Modernist Studies (about Sylvia Plath and Edith Sitwell), and The Conversation (about Tupperware). Professor Bryant’s book Women’s Poetry and Popular Culture received funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities. She is a member of UF’s Academy of Distinguished Teaching Scholars and a UF Doctoral Mentor awardee. Professor Bryant is also Associate Editor of Contemporary Women’s Writing.

- Roland Barthes, Mythologies, trans. Annette Lavers (New York: Hill and Wang, 1987), 87, http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/18888151. ↵

- Barthes, Mythologies, 97. ↵

- Alison J. Clarke, Tupperware: The Promise of Plastic in 1950s America (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1999), 137, http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/634385344. ↵

- Robert Friedel, Pioneer Plastic: The Making and Selling of Celluloid (Madison: Univ. of Wisconsin Press, 1983), 108–109, http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/9081371. ↵

- Vincent Valk, "Outlook 2014: Looking Forward," IHS Chemical Week, April 14, 2014, http://www.chemweek.com/lab/Outlook-2014-Looking-forward_57898.html. ↵

- Bob Kealing, Tupperware Unsealed: Brownie Wise, Earl Tupper, and the Home Party Pioneers (Gainesville: Univ. Press of Florida, 2008), 22, http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/185123372. ↵

- Clarke, Tupperware, 4. ↵

- Clarke, Tupperware, 8–12, 15–17, 19–20; "Earl Silas Tupper," American Experience, PBS, http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/biography/tupperware-tupper/. ↵

- Qtd. in Kealing, Tupperware Unsealed, 10. ↵

- Clarke, Tupperware, 10, 64, 114. ↵

- Clarke, 26–29, 37–38. ↵

- Kealing, Tupperware Unsealed, 21. ↵

- Clarke, 30–34. ↵

- Kealing, 21–22. ↵

- Clarke, 42, 49. ↵

- Elaine Tyler May, Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era, 20th Anniversary Ed. (New York: Basic Books, 2008), 13, http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/690487945. ↵

- May, 207. ↵

- Qtd. in Kealing, Tupperware Unsealed, 26. ↵

- Qtd. in Kealing, 38. ↵

- Kealing, 44. ↵

- Qtd. in Kealing, 23. ↵

- Juliann Sivulka, Soap, Sex, and Cigarettes: A Cultural History of American Advertising, 2nd ed. (Boston: Wadsworth, 2012), 231, http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/714878884. ↵

- Jesse Hicks, "Thanks to Chemistry, A Fresh Breath," Chemical Heritage Foundation, https://web.archive.org/web/20160407023152/http://www.chemheritage.org:80/discover/online-resources/thanks-to-chemistry/listerine.aspx ↵

- Roland Marchand, Advertising the American Dream: Making Way for Modernity, 1930–1940 (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1985), 210, http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/35117815. ↵

- Sivulka, Soap, Sex, and Cigarettes, 232. ↵

- Rosser Reeves, Reality in Advertising (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1968), 79, http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/7540914. ↵

- David Ogilvy, Ogilvy on Advertising, 1983 (New York: Vintage, 1985), 14, http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/613287090. ↵

- Sivulka, Soap, Sex, and Cigarettes, 236. ↵

- Qtd. in Kealing, Tupperware Unsealed, 56. ↵

- UltraPro Ovenware product insert, Tupperware. ↵

Feedback/Errata