5.3 Conducting Audience Analysis — Stand up, Speak out

5.3 Conducting Audience Analysis

Learning Objectives

- Learn several tools for gathering audience information.

- Create effective tools for gathering audience information.

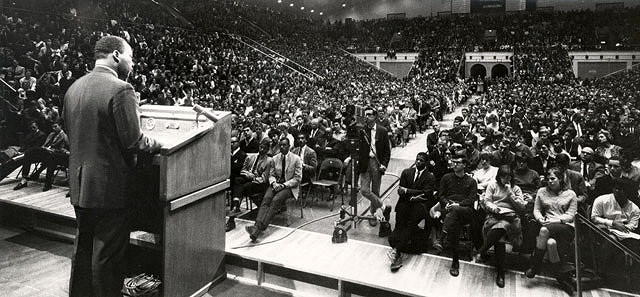

Penn State – MLK speaking to a crowd at Rec Hall – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Now that we have described what audience analysis is and why it is important, let’s examine some details of how to conduct it. Exactly how can you learn about the people who will make up your audience?

Direct Observation

One way to learn about people is to observe them. By observing nonverbal patterns of behavior, you can learn a great deal as long as you are careful how you interpret the behaviors. For instance, do people greet each other with a handshake, a hug, a smile, or a nod? Do members of opposite sexes make physical contact? Does the setting suggest more conservative behavior? By listening in on conversations, you can find out the issues that concern people. Are people in the campus center talking about political unrest in the Middle East? About concerns over future Pell Grant funding? We suggest that you consider the ethical dimensions of eavesdropping, however. Are you simply overhearing an open conversation, or are you prying into a highly personal or private discussion?

Interviews and Surveys

Because your demographic analysis will be limited to your most likely audience, your most accurate way to learn about them is to seek personal information through interviews and surveys. An interview is a one-on-one exchange in which you ask questions of a respondent, whereas a survey is a set of questions administered to several—or, preferably, many—respondents. Interviews may be conducted face-to-face, by phone, or by written means, such as texting. They allow more in-depth discussion than surveys, and they are also more time consuming to conduct. Surveys are also sometimes conducted face-to-face or by phone, but online surveys are increasingly common. You may collect and tabulate survey results manually, or set up an automated online survey through the free or subscription portals of sites like Survey Monkey and Zoomerang. Using an online survey provides the advantage of keeping responses anonymous, which may increase your audience members’ willingness to participate and to answer personal questions. Surveys are an efficient way to collect information quickly; however, in contrast to interviews, they don’t allow for follow-up questions to help you understand why your respondent gave a certain answer.

When you use interviews and surveys, there are several important things to keep in mind:

- Make sure your interview and survey questions are directly related to your speech topic. Do not use interviews to delve into private areas of people’s lives. For instance, if your speech is about the debate between creationism and evolution, limit your questions to their opinions about that topic; do not meander into their beliefs about sexual behavior or their personal religious practices.

- Create and use a standard set of questions. If you “ad lib” your questions so that they are phrased differently for different interviewees, you will be comparing “apples and oranges” when you compare the responses you’ve obtained.

- Keep interviews and surveys short, or you could alienate your audience long before your speech is even outlined. Tell them the purpose of the interview or survey and make sure they understand that their participation is voluntary.

- Don’t rely on just a few respondents to inform you about your entire audience. In all likelihood, you have a cognitively diverse audience. In order to accurately identify trends, you will likely need to interview or survey at least ten to twenty people.

In addition, when you conduct interviews and surveys, keep in mind that people are sometimes less than honest in describing their beliefs, attitudes, and behavior. This widely recognized weakness of interviews and survey research is known as socially desirable responding: the tendency to give responses that are considered socially acceptable. Marketing professor Ashok Lalwani divides socially desirable responding into two types: (1) impression management, or intentionally portraying oneself in a favorable light and (2) self-deceptive enhancement, or exaggerating one’s good qualities, often unconsciously (Lalwani, 2009).

You can reduce the effects of socially desirable responding by choosing your questions carefully. As marketing consultant Terry Vavra advises, “one should never ask what one can’t logically expect respondents to honestly reveal” (Vavra, 2009). For example, if you want to know audience members’ attitudes about body piercing, you are likely to get more honest answers by asking “Do you think body piercing is attractive?” rather than “How many piercings do you have and where on your body are they located?”

Focus Groups

A focus group is a small group of people who give you feedback about their perceptions. As with interviews and surveys, in a focus group you should use a limited list of carefully prepared questions designed to get at the information you need to understand their beliefs, attitudes, and values specifically related to your topic.

If you conduct a focus group, part of your task will be striking a balance between allowing the discussion to flow freely according to what group members have to say and keeping the group focused on the questions. It’s also your job to guide the group in maintaining responsible and respectful behavior toward each other.

In evaluating focus group feedback, do your best to be receptive to what people had to say, whether or not it conforms to what you expected. Your purpose in conducting the group was to understand group members’ beliefs, attitudes, and values about your topic, not to confirm your assumptions.

Using Existing Data about Your Audience

Occasionally, existing information will be available about your audience. For instance, if you have a student audience, it might not be difficult to find out what their academic majors are. You might also be able to find out their degree of investment in their educations; for instance, you could reasonably assume that the seniors in the audience have been successful students who have invested at least three years pursuing a higher education. Sophomores have at least survived their first year but may not have matched the seniors in demonstrating strong values toward education and the work ethic necessary to earn a degree.

In another kind of an audience, you might be able to learn other significant facts. For instance, are they veterans? Are they retired teachers? Are they members of a voluntary civic organization such as the Lions Club or Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD)? This kind of information should help you respond to their concerns and interests.

In other cases, you may be able to use demographics collected by public and private organizations. Demographic analysis is done by the US Census Bureau through the American Community Survey, which is conducted every year, and through other specialized demographic surveys (Bureau of the Census, 2011; Bureau of the Census, 2011). The Census Bureau analysis generally captures information about people in all the regions of the United States, but you can drill down in census data to see results by state, by age group, by gender, by race, and by other factors.

Demographic information about narrower segments of the United States, down to the level of individual zip codes, is available through private organizations such as The Nielsen Company (http://www.claritas.com/MyBestSegments/Default.jsp?ID=20&SubID=&pageName=ZIP%2BCode%2BLook-up), Sperling’s Best Places (http://www.bestplaces.net), and Point2Homes (http://homes.point2.com). Sales and marketing professionals use this data, and you may find it useful for your audience analysis as well.

Key Takeaways

- Several options exist for learning about your audience, including direct observation, interviews, surveys, focus groups, and using existing research about your audience.

- In order to create effective tools for audience analysis, interview and survey questions must be clear and to the point, focus groups must be facilitated carefully, and you must be aware of multiple interpretations of direct observations or existing research about your audience.

Exercises

- Write a coherent set of four clear questions about a given issue, such as campus library services, campus computer centers, or the process of course registration. Make your questions concrete and specific in order to address the information you seek. Do not allow opportunities for your respondent to change the subject. Test out your questions on a classmate.

- Write a set of six questions about public speaking anxiety to be answered on a Likert-type scale (strongly agree, agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree, and strongly disagree).

- Create a seven-question set designed to discover your audience’s attitudes about your speech topic. Have a partner evaluate your questions for clarity, respect for audience privacy, and relevance to your topic.

References

Bureau of the Census. (2011). About the American community survey. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/acs/www/about_the_survey/american_community_survey/.

Bureau of the Census. (2011). Demographic surveys. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/aboutus/sur_demo.html

Lalwani, A. K. (2009, August). The distinct influence of cognitive busyness and need for closure on cultural differences in socially desirable responding. Journal of Consumer Research, 36, 305–316. Retrieved from http://business.utsa.edu/marketing/files/phdpapers/lalwani2_2009-jcr.pdf

Vavra, T. G. (2009, June 14). The truth about truth in survey research. Retrieved from http://www.terryvavra.com/customer-research/the-truth-about-truth-in-survey-research