Module 5: Management and Prevention of Disease Outbreaks

Assessment of Infection Risk for Quarantined Animals

Quarantined animals that are healthy can be assessed for their risk of infection. This provides a humane and cost-effective strategy for quickly moving animals out of quarantine, thereby relieving the strain created by utilizing housing for quarantine. The risk assessment is based on 2 approaches:

- Test for pre-existing protective antibody titers to the pathogen

- Test for the pathogen itself

Although no risk assessment is 100% accurate, when used and interpreted appropriately these approaches can predict in most cases which animals are safe to release and which animals are at risk for infection and need to stay in quarantine.

Immunity Status

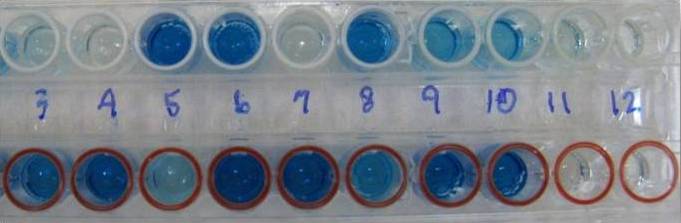

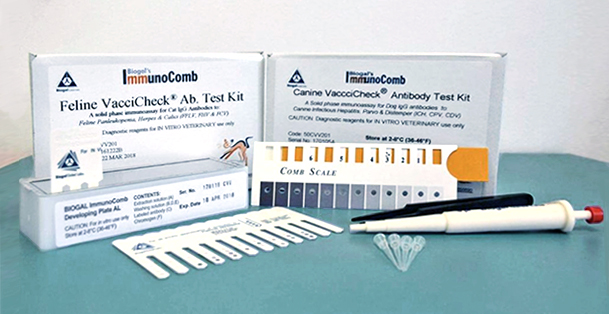

Due to the availability of point-of-care kits, animals exposed to CDV, CPV, or FPV can be tested for protective levels of antibodies to these pathogens in healthy exposed animals. These kits require very small amounts of serum, include all the needed reagents and supplies, provide results in 20 minutes, can be easily performed by shelter staff, and cost around $15/sample.

There are no point-of-care tests for assessing presence of protective antibody titers for CnPnV and CIV. Antibody titers do not correlate with protection from infection by FHV and FCV.

The CDV/CPV TiterChek kit (Zoetis) and the Canine Vaccicheck kit (Biogal) determine whether a dog has protective antibody titers to CDV and CPV. The Feline Vaccicheck kit (Biogal) determines whether a cat has protective antibody titers for FPV.

Antibody titer testing is useful for quick release of quarantined animals during CDV, CPV, or FPV outbreaks. Protective antibody titers correlate with protection from infection by CDV, CPV, or FPV. However, the antibody titer kits cannot differentiate between antibodies induced by vaccination vs. infection. To reduce the possibility of detecting an antibody response in an animal with subclinical infection, it is preferable to test for protective immunity at the time of exposure but at least within the first week of exposure. After this time period, detection of antibodies may represent an immune response to infection.

Here are tips for using antibody titer testing for assessing risk for infection:

- Perform testing preferably at the time of exposure but at least within the first week of exposure

- Test only asymptomatic adult animals (≥6 mo old). Those with protective antibody titers are low risk for infection and can be released from quarantine.

- Adults without protective antibody titers are high risk. Re-vaccinate and keep in quarantine in the shelter or transfer to a foster home for completion of the quarantine.

- Don’t test puppies and kittens <6 mo old. This age group is always high risk for infection because of maternal antibody interference with response to vaccination.

- The antibody titer tests cannot differentiate maternal antibodies from those induced by vaccination.

- Protective titers due to maternal antibodies are transient and disappear quickly, leaving the puppy or kitten unprotected from infection.

- Keep puppies and kittens in quarantine in the shelter or transfer to a foster home and continue DAPP or FVRCP vaccination every 2 weeks

Test Your Knowledge

Review the case description and test results below, then answer the questions.

Two adult stray dogs in a Texas shelter developed purulent nasal discharge and a slight cough 2 days after admission. They were diagnosed with CDV infection by PCR testing of nasal and oropharyngeal swabs collected 4 days later. Based on the typical 2-week incubation period for CDV, these dogs were infected and shedding virus before entering the shelter. There were 25 other adult dogs in the same housing area and none of them had any clinical signs. All of the dogs had received their intake DAPP vaccine 7 to 10 days before admission of the two infected dogs. The shelter closed the housing area to quarantine the 25 exposed dogs and collected blood samples to test for CDV antibodies to assess their risk for acquiring infection after 6 days of exposure. They used the Zoetis CDV/CPV TiterChek kit to determine which dogs had protective antibody titers.

| Dog ID | Intake Type | Age | CDV protective antibody titer |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1547105 | Owner Surrender | Adult | no |

| 1547107 | Owner Surrender | 6 mo | no |

| 1565412 | Stray | Adult | yes |

| 1565414 | Stray | Adult | no |

| 1565415 | Stray | Adult | no |

| 1565419 | Stray | Adult | no |

| 1565490 | Stray | Adult | no |

| 1565514 | Owner Surrender | Adult | no |

| 1565515 | Owner Surrender | Adult | no |

| 1565536 | Stray | Adult | no |

| 1565554 | Stray | Adult | yes |

| 1565578 | Stray | Adult | yes |

| 1565582 | Stray | Adult | no |

| 1565603 | Stray | Adult | yes |

| 1565619 | Stray | Adult | no |

| 1565621 | Stray | Adult | no |

| 1565633 | Stray | Adult | yes |

| 1565637 | Stray | Adult | no |

| 1565646 | Stray | Adult | no |

| 1565652 | Stray | Adult | no |

| 1565653 | Stray | Adult | yes |

| 1565757 | Stray | Adult | yes |

| 1565784 | Stray | Adult | yes |

| 1565797 | Stray | Adult | yes |

| 1565800 | Owner Surrender | Adult | yes |

Answer the following questions regarding infection risk assessment for the quarantined dogs.

Test Your Knowledge

Review the case description and test results below, then answer the questions.

The cat room at a private nonprofit humane society shelter in Florida houses a mix of adult cats and kittens. On August 1st, a litter of kittens that were anorectic and had diarrhea were diagnosed with FPV. This litter had been in the room for 6 days before diagnosis. There were 12 adult cats and 10 other kittens in the room on August 1st. The shelter closed the cat room to quarantine the 22 exposed cats. Blood samples were collected from the adult cats on August 3rd to test for protective antibody titers to FPV using the Feline Vaccicheck kit.

| Name | Age | Intake FVRCP Date | Known Exposure Date | Serum Sample Date | FPV Protective Antibody Titer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sullivan | 6 y | 7/24 | 8/1 | 8/3 | yes |

| Pomegranate | 1 y | 7/24 | 8/1 | 8/3 | no |

| Genoa | 2 y | 7/26 | 8/1 | 8/3 | yes |

| Tizzy | 2 y | 7/26 | 8/1 | 8/3 | no |

| Hershey | 6 y | 7/26 | 8/1 | 8/3 | yes |

| Mistletoe | 5 y | 7/26 | 8/1 | 8/3 | yes |

| Emu | 1 y | 7/26 | 8/1 | 8/3 | no |

| Mystique | 3 y | 7/28 | 8/1 | 8/3 | yes |

| Sunny | 6 y | 7/29 | 8/1 | 8/3 | yes |

| Bubba | 5 y | 7/31 | 8/1 | 8/3 | yes |

| Motely | 3 y | 7/31 | 8/1 | 8/3 | yes |

| Ziggie | 1 y | 7/31 | 8/1 | 8/3 | no |

Answer the following questions regarding infection risk assessment for the quarantined cats.

Test Your Knowledge

Review the case description and test results below, then answer the questions.

A municipal shelter in Kentucky was experiencing a widespread CDV outbreak in their population of 200 dogs. There had been a slowly increasing number of dogs with “kennel cough” for at least a month before diagnostic testing confirmed CDV in 61 symptomatic dogs. Blood samples were collected from 139 exposed asymptomatic adult dogs to test for protective antibody titers to CDV using the Canine Vaccicheck kit. Nasal and oropharyngeal swabs were collected at the same time for the Idexx CDV PCR test.

| Number of dogs | CDV protective antibody titer | Infection risk based on antibody titer test | CDV PCR test | Eventual outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 53 | no | high | all were positive | all developed illness |

| 86 | yes | low | all were positive | 55% developed illness |

Answer the following questions regarding infection risk assessment based on antibody titer testing for the quarantined dogs.

Infection Status

To reduce the time in quarantine, asymptomatic animals can be assessed for infection with the same test used to diagnose the pathogen. Testing for the pathogen is more reliable than antibody titer testing, but is much more expensive. There are other advantages of testing for the pathogen rather than antibody. One is that it detects pathogen shedding in animals with subclinical infections or in the late incubation phase. The other is that it can be applied to puppies and kittens as well as adults.

Canine and Feline Respiratory Pathogens

For the canine and feline respiratory pathogens, PCR testing of swabs from the upper respiratory tract is the most accurate and timely test. With the exception of CDV, the quarantine time for the canine and feline respiratory pathogens is short based on the 1-week incubation periods, so PCR testing may not provide any real advantage for early release. If the shelter desires to confirm the infection status before releasing from quarantine, then PCR testing can be performed.

CDV

Dogs in quarantine for CDV should not be tested by PCR until at least 10-12 days have elapsed. This allows for systemic spread of virus that typically occurs on day 7 after infection, followed by high levels of virus replication in the respiratory epithelium by days 10-12. Testing before this time can result in false negative PCR tests. Asymptomatic animals that are PCR-negative after day 10 are low risk and can be moved out of quarantine. Those that are PCR-positive should be moved to isolation.

It may not be feasible for shelters to test all exposed dogs due to costs. In this case, CDV PCR can be performed on pooled swabs from several dogs that are submitted to the lab as one sample. Pooling swabs will not dilute out the virus as it does for blood or fecal tests. Positive results for a pool trigger re-testing of each dog in the pool to determine who is infected. To reduce the number of positive pools and thus number of dogs for individual testing, it is best to group dogs into pools based on age, number of vaccines, and time since the last vaccine. The best pool size has not been determined for CDV PCR, but studies on COVID PCR testing have shown that pools should not exceed 5 individuals for best accuracy.

A Novel Approach to Eliminating Canine Distemper from a Shelter

A large municipal shelter in Texas had endemic canine distemper virus infection in their dog population for years. This shelter routinely cares for 30,000 animals each year, admits about 100 new dogs each day, and typically houses 600 to 700 dogs per day. Due to lack of proper housing capacity, multiple dogs were co-housed together per run. Staff was overwhelmed by the number of dogs (and cats) in their care and vaccination was often neglected. There was no veterinarian on-site and no effective disease prevention or surveillance policy.

When the shelter recently hired their first full-time veterinarian, one of her high priority tasks was to contain and hopefully eradicate distemper as this was causing large loss of life and a negative reputation for the shelter. To determine the prevalence of CDV in the shelter and the housing areas most impacted, she collected swabs from 169 dogs over a 2-month period for CDV PCR testing. The results showed that 40% of the tested dogs had distemper and the infected dogs were located in all housing areas, suggesting that most dogs in the shelter had been exposed.

The shelter veterinarian requested on-site assistance from the UF Shelter Medicine team to eliminate the endemic distemper without resorting to depopulation. The goal was to determine the infection status of all dogs in the shelter through CDV PCR testing. The desired outcome was to break the chain of virus transmission by prompt removal of infected dogs from the population and movement of negative dogs out via fee-waived adoptions, transfer to rescue groups, and transport to other shelters. The shelter had no space for isolation and quarantine.

There were 685 dogs in the shelter at the time and CDV PCR testing of each dog would take more than a week and cost $41,000. Since multiple dogs were housed in each run, the UF team decided to make the testing more feasible and timely by collecting a swab from each dog in a run and pooling the swabs together as one sample. There were 225 pools with 3 to 5 dogs per pool, the testing was completed in 4 days, and the total cost was $13,500.

Of the 225 pools, 19 pools had positive CDV PCR results, representing 77 dogs. Since there was no isolation or quarantine capacity, the shelter elected euthanasia for all the dogs in the positive pools to curtail virus transmission. Other shelters with more resources may have elected to re-test each dog in a positive pool to separate infected from exposed dogs.

This novel pooled testing method facilitated the quick identification and removal of infected and highly exposed dogs from the shelter. With implementation of more progressive population management strategies, better vaccination practices, daily rounds, and disease surveillance testing, there has been very little in-shelter CDV transmission for the past 2 years.

Using a combination of CDV PCR testing of swabs and CDV antibody testing on serum is the most accurate way to triage exposed dogs out of quarantine. In this approach, paired swab and serum samples are collected at the same time from each dog, starting on day 1 of the quarantine instead of waiting 10-12 days for PCR testing only. Here are the possible test outcomes and actions:

| CDV PCR | CDV Antibody | Status | Action |

| Negative | Positive | Uninfected/immune | Release from quarantine |

| Negative | Negative | Uninfected/not immune | Keep in quarantine/revaccinate |

| Positive | Neg or Pos | Infected | Move to isolation |

Canine and Feline Parvovirus

The point-of-care CPV/FPV antigen tests are not very sensitive because they require a large amount of virus for detection. The low sensitivity (<85%) means that these antigen tests are not very accurate for screening exposed asymptomatic animals - animals shedding low amounts of virus will have false negative results. PCR testing of feces for CPV or FPV is very sensitive and detects very small amounts of virus. However, PCR also detects CPV and FPV vaccine strains shed in feces for up to 2 weeks post-vaccination, causing false positive test results. A negative PCR result indicates the animal is a low risk for infection and can be moved out of quarantine.

Feline Ringworm

Quarantined cats exposed to ringworm can be assessed for infection by performing a Wood’s Lamp exam and trichogram. Cats with negative Wood’s Lamp and trichogram results are low risk and can be dipped once in lime sulfur and moved out of quarantine. Some exposed cats without skin lesions test false positive with a Wood’s lamp exam and/or trichogram due to M canis carriage on their fur. These “fomite” or “dust mop” cats are not truly infected and can be dipped once in lime sulfur and moved out of quarantine. Quarantined cats with skin lesions and a positive Wood’s Lamp and/or trichogram are infected and should be moved to isolation for confirmation by ringworm PCR testing and treatment.