Module 4: Healthcare practices for common contagious infectious diseases

Deciding to Treat the Common Contagious Diseases

When money is scarce, space for isolation of contagious animals is limited, and staff are already stretched too thin, how do you select the best treatment plan to recommend? Which animals and diseases do you select for in-shelter treatment?

As with most things in shelters, there are no simple answers to such questions. Shelters must continually balance the needs of the individual animal, the shelter population, and the sustainability of the organization. Decisions about which animals to treat and how to treat varies between shelters based on the mission of the shelter as well as available resources. Making the right decision hinges on balancing resources for successful treatment of the individual patient with resources needed to protect the health and welfare of the whole population.

Availability of appropriate isolation, trained medical care staff, veterinarian supervision, and funding should be carefully assessed to determine whether shelter-based treatment is the right choice or not for any of the Top 5 contagious diseases presented in this Module. According to the ASV Guidelines, a shelter’s capacity to provide medical care for individual animals is impacted by:

- the availability of resources to safely and humanely provide treatment and maintain welfare during the treatment period

- the duration of care

- the number of animals needing treatment

- likelihood and consequences of disease transmission

- the likelihood of recovery

- and the animal’s potential for a live outcome

Each pathogen's properties (transmission route, shedding time, carrier state, persistence in the environment) are also important factors in the decision-making process.

The ASV Guidelines for disease response provide guiding principles for decisions about which contagious diseases are treatable in a particular shelter and which are not.

ASV Guidelines

- Treatment decisions balance both the best interest of the individual animals requiring treatment and the shelter population as a whole

- Shelters should have a protocol for making decisions about which animals and conditions to treat, and which animals and conditions they cannot treat

Shelter Resources Comparison

The table below shows the statistics and resources for Shelter A and Shelter B.

| Shelter A | Shelter B | |

|---|---|---|

| Shelter type | Open admission municipal | Limited admission private nonprofit |

| Annual admissions | 5,000 dogs/5,000 cats | 2,500 dogs/2,500 cats |

| Live release rate for dogs | 85% | 96% |

| Average daily dog census | 250 | 95 |

| Number of dog runs | 100 | 100 |

| Kennel staff | 4 (2 on weekends/holidays) | 6 (3 on weekends/holidays) Volunteers on weekends |

| Veterinarian | 1 part-time (3 days/week) | 1 full-time/1 part-time (7-day coverage) |

| Medical care staff | 2 (Mon-Fri) | 4 (7-day coverage) |

| Annual medical services budget | $500,000 | $1,500,000 |

| Isolation Ward | Cages/crates in staff breakroom | Separate dedicated room |

Both shelters want to save CPV-infected puppies. Think about how well each shelter is functioning with regard to housing and staffing capacity for care of the daily dog census. Think about the level of care required for CPV patients (fluid therapy, injectable medications, frequent monitoring of clinical status), the availability of a veterinarian and trained medical staff to deliver care without neglecting other duties, and the need for strict biosecurity to prevent spread of disease. What if the CPV treatment cost is $500 per dog?

Test Your Knowledge

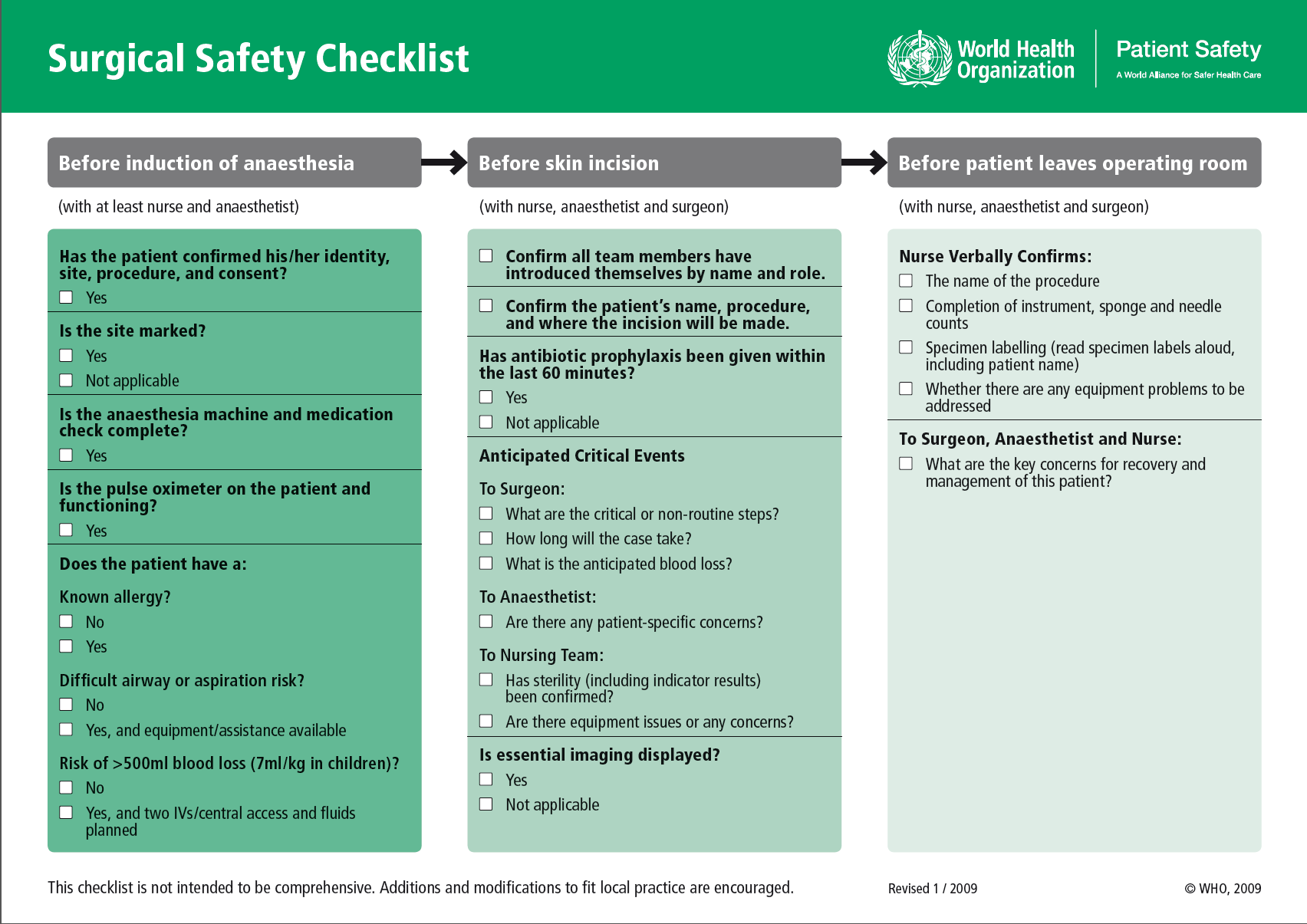

Once the shelter determines which contagious diseases are treatable in their setting, the veterinarian must develop evidence-based protocols that include steps for isolation of sick animals, diagnostic testing, treatment, monitoring response to treatment, when to release from isolation, and biosecurity measures to prevent contamination and spread of disease.

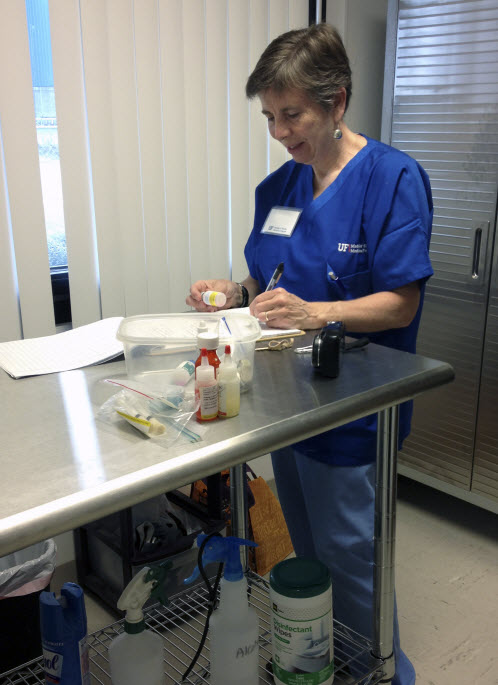

In addition to detailed step-by-step protocols, other valuable tools for guiding selection of animals to treat and execution of the treatment process include flowcharts and checklists. These tools support consistency and safety in patient care by reducing medical errors and enhancing communication between team members.

Flowcharts

A flowchart is a visual or pictorial display of the sequential step-by-step process of a procedure or protocol. Flowcharts are also called algorithms and decision trees. The flowchart provides the “big picture” overview of a protocol and the pivotal steps where decisions are made before proceeding to the next step. Flowcharts reduce errors, promote consistency, and improve workflow and communication of healthcare team members. See the example flowchart outlining steps for medical student selection of their specialty.

This flowchart guides veterinarians in admission of pets while minimizing exposure to the SARS CoV2 virus.

Checklists

Human error in providing care to patients is inevitable. A 2018 survey on the prevalence of medical errors (JAVMA March 1,2018;252(5):586-595) reported that 73% of the 606 responding veterinarians had been involved in at least one medical error affecting patient safety. Another study that evaluated medical errors in a large veterinary teaching hospital (Frontiers in Veterinary Science Feb 2019; https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2019.00012) found an average of 3 to 4 errors in patient care per week and 15% of these errors caused patient harm while 8% caused permanent damage or death. More than half of the errors were related to failures in communication between medical staff and to incoorect doses for medications.

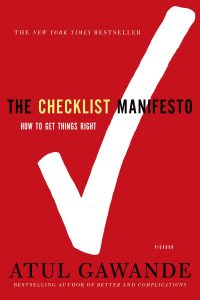

Checklists are used in healthcare systems to guide staff through complex medical procedures consisting of multiple small steps. A checklist is a concise list of essential action items in a SOP. Checklists promote adherence to evidence-based practices, minimize error, protect the patient, improve workflow, and enhance communication between team members.

Dr. Atul Gawande, surgeon at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and professor of surgery and public health at Harvard Medical School, authored The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right in which he examines the outcomes of checklists used in the medical profession, aviation industry, and business world.

Watch This

Here are examples of checklists used in veterinary medicine.

This surgical safety checklist reduces surgical errors and postoperative complications.

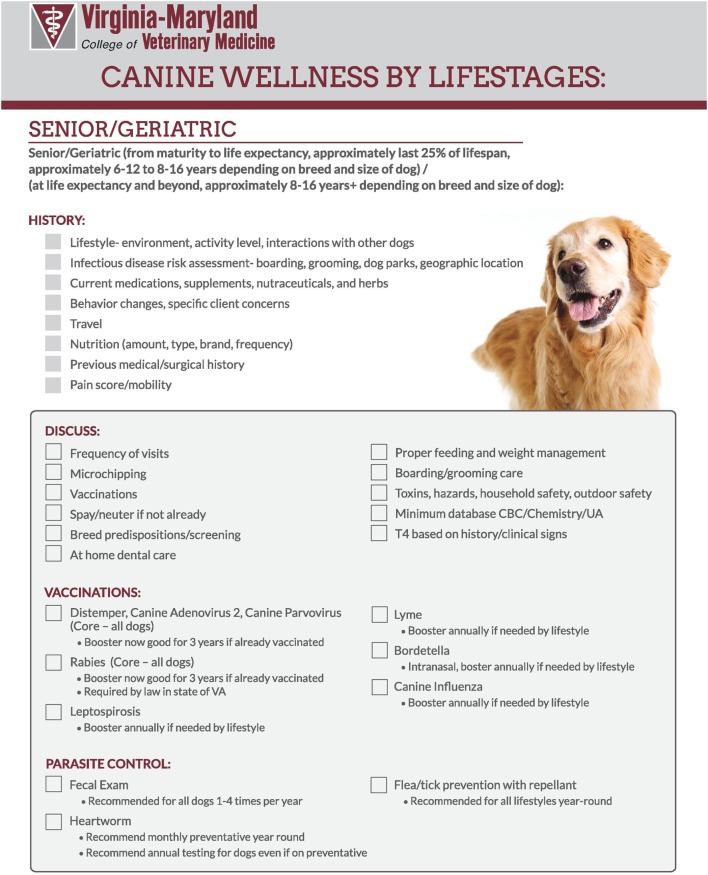

This checklist outlines preventive healthcare procedures for wellness visits.

Here is a flowchart to help shelters determine if they have the proper capacity and resources to treat dogs infected with CPV.