Module 5: Management and Prevention of Disease Outbreaks

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is essential for successful control and resolution of disease outbreaks. Timely diagnosis substantially impacts how many dogs and cats remain healthy and adoptable. No diagnosis or late diagnosis increases the number of sick and exposed animals due to improper management and ultimately the number of animals euthanized.

Diagnosis directs the management strategy for interruption and resolution of disease transmission throughout the population.

Why test?

Diagnosis provides the following:

- Proper treatment of each animal

- Prognosis for recovery and average time to recovery

- Quarantine time = incubation period for the pathogen

- Isolation time = duration of pathogen shedding (contagious period)

- Pathogen transmission routes important for biosecurity

- Disinfectants required for pathogen inactivation

- Best strategy for preventing recurrence

Even shelters with tight budgets should invest in diagnostic testing since this is the key to management and prevention strategies. It is far more costly to base these core strategies on guesswork and trial by error, both in terms of the financial burden as well as the suffering of the animals and the shelter’s reputation.

Who and when to test?

Diagnostic testing should be conducted on both sick animals and asymptomatic exposed animals. Diagnostic test accuracy is dependent upon the timing of sample collection with the periods when the suspected pathogens are shed in highest amount. For respiratory pathogens, the largest amounts of shedding occur during the preclinical incubation period and the acute phase of illness (sick for ≤4 days). At least 5 to 10 cases of the combined sick and exposed population should be tested in order to identify a pattern and improve the accuracy and reliability of the results.

Since FHV and FCV cause 80-90% of feline URI cases in shelter cats, there is no advantage to testing URI cats to confirm these pathogens as the cause of widespread respiratory illness. However, the shelter should invest in diagnostic testing when cats have more severe or prolonged clinical disease, including pneumonia or coughing, to rule out involvement of other pathogens such as Bordetella or Strep zoo or a novel influenza virus.

For the parvoviruses, dogs and cats should be tested at the onset of compatible clinical signs such as anorexia, fever, vomiting, and/or diarrhea. The first 1 to 3 days of illness corresponds to peak virus shedding in feces.

For ringworm, all cats with skin lesions should be screened for M. canis infection.

What test?

Not all diagnostic tests are created equal with regard to accuracy. Shelter personnel should consult with infectious disease experts when deciding on what diagnostic tests are most appropriate and reliable and provide the quickest turnaround time for results. Diagnostic tests that detect the pathogen in some body secretion or excretion are more desirable than those that detect antibodies to the pathogen since this approach is easily confounded by prior vaccinations or exposures. In addition, diagnostic tests that provide rapid results support the timely management of the population at risk.

For parvoviruses, the point-of-care CPV/FPV antigen detection kits require a large amount of virus in the sample to register a positive result. False negatives occur with virus amounts below the threshold for detection. For animals strongly suspected to have parvovirus infection based on clinical signs and history, the antigen test should be repeated daily for 2 to 3 days before ruling out parvoviral infection. In general, a positive CPV/FPV antigen test in an animal with compatible clinical signs is most likely correct, whereas a negative test does not rule out infection. Alternatively, PCR testing can be performed on fecal samples. PCR tests are highly sensitive and can detect minute amounts of parvovirus in a sample. However, these tests also detect the small amounts of CPV or FPV vaccine strains shed in feces for 2 weeks after vaccination, resulting in a false positive test result.

For respiratory infections, PCR testing of swabs from the nasal cavity and oropharyngeal cavity is the best diagnostic approach.

-

Swab collection on a dog

-

Swab collection on a cat

The comprehensive canine and feline respiratory PCR panels are very sensitive and specific with a quick turnaround in results. A low percentage of dogs and cats vaccinated within 7 to 14 days before sampling can have false positive results due to detection of the modified-live vaccine strains replicating in the upper respiratory tract. In these cases, the respiratory PCR tests should be repeated in 5 to 7 days. If the tests are still positive, then the animal is truly infected with a virulent pathogen.

For ringworm, a combination of the Wood’s Lamp exam, trichogram, and ringworm PCR is the best diagnostic approach for initial identification of M. canis-infected cats.

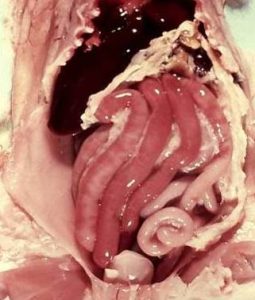

The most valuable diagnostic test frequently overlooked by shelters is necropsy – animals that die or are euthanized due to illness can yield the most clues for solving the diagnostic puzzle. Tissues from affected target organs can be submitted to pathology laboratories for histopathology and diagnostic testing. For suspect parvoviral infections, this includes the tongue and jejunal segments. For respiratory infections, samples of normal and abnormal lung are the primary tissue, but also include the urinary bladder for CDV suspects as this tissue contains large amounts of replicating virus.

-

Intestines of a kitten that died from suspect feline parvovirus enteritis

-

Lungs from a dog that died from suspect canine distemper pneumonia