Module 5: Management and Prevention of Disease Outbreaks

Risk Factors for Disease Outbreaks

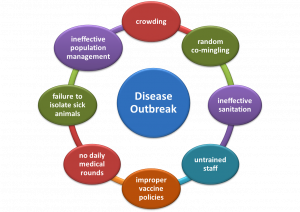

Every shelter has inherent risk for a disease outbreak and this risk cannot be eliminated, even by the best management practices. Risk factors for disease outbreaks in shelters are mostly associated with prolonged length of stay and crowding due to ineffective population management practices. Longer stays in the shelter result in saturating the housing capacity of the facility, crowding of numerous animals into each housing area, and increased stress for the animals and staff. Crowding hampers effective sanitation, which increases the infectious dose of pathogens in the environment. Staff that are not trained to recognize sick animals and follow a plan for prompt isolation from the general population contribute to increased pathogen transmission and infectious dose in the environment.

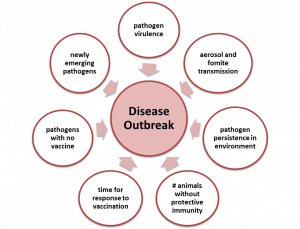

Other risk factors include pathogen virulence, pathogen transmission by aerosols and fomites, persistence of the pathogen in the environment, number of animals without protective immunity, time required to respond to vaccination, pathogens for which there is no protective vaccine, and newly emerging pathogens that may not be recognized and for which the population has no immunity.

No or incomplete immunity

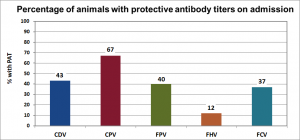

The UF Shelter Medicine Program performed studies to determine immunity to common pathogens in Florida shelters. Blood samples were collected from 431 dogs and 347 cats on entry into the shelter before vaccination. Antibody titers to the following common pathogens were measured to determine the proportion of animals with pre-existing protective antibody titers (PAT).

- Canine distemper virus (CDV)

- Canine parvovirus (CPV)

- Feline parvovirus (FPV)

- Feline herpesvirus (FHV)

- Feline calicivirus (FCV)

Less than half of dogs and cats entering Florida shelters had protective antibody titers (PAT) to CDV, FPV, FHV, and FCV.

Less than half of dogs and cats entering Florida shelters had protective antibody titers (PAT) to CDV, FPV, FHV, and FCV.

The antibody titer data were analyzed by age groups. Most puppies and kittens <6 months old had no protective immunity to the common contagious pathogens in shelters. About half of young adults between 1 and 2 years of age, the most common age group entering shelters, did not have protective immunity with the exception to CPV. In contrast, a large proportion of older dogs and cats had protective immunity to CDV, CPV, FPV, FHV, and FCV at the time they entered shelters.

Percentage of Animals with PAT

| Age | CDV | CPV | FPV | FHV | FCV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 6 mo | 17% | 36% | 34% | 1% | 16% |

| 1 to 2 yr | 48% | 76% | 54% | 28% | 58% |

| > 2 yr | 75% | 89% | 64% | 50% | 79% |

Response to vaccination

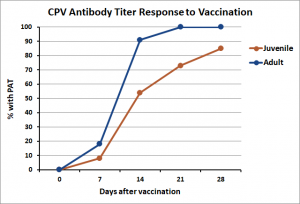

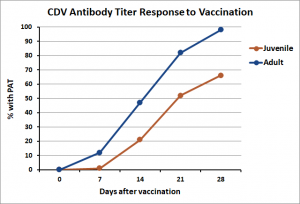

The UF Shelter Medicine Program also performed studies to determine how long it takes shelter dogs to develop protective antibody titers (PAT) to CDV and CPV after intake vaccination. The study included 68 juveniles (younger than 6 months) and 118 adults (6 month or older), all without antibodies on entry. All the seronegative dogs received a DAPP vaccine on day of entry. Blood samples were collected from the dogs every week after vaccination to measure antibody titers to CDV and CPV and determine when protective titers were achieved.

In response to DAPP vaccination at admission, nearly all of the adult dogs had developed PAT to CPV by 2 weeks compared to only half of the puppies. Most of the puppies had CPV PAT by 4 weeks after vaccination.

In contrast, only half of the adult dogs and 20% of the puppies had PAT to CDV by 2 weeks post-vaccination. Nearly all of the adults had CDV PAT by 4 weeks but 33% of the puppies had still not fully responded by 4 weeks.

Overall, adult dogs responded more quickly to intake vaccination than puppies, and the response to CPV was faster than to CDV. The 2-to 4-week time for response to DAPP vaccination at intake creates a pool of unprotected dogs that contribute to risk for disease outbreaks in shelters. While vaccination is vital to increasing population immunity in a shelter, the slow response time, particularly in puppies, requires additional strategies to protect at-risk dogs

What do these results mean?

It is clear from these studies that large numbers of dogs and cats enter shelters without protective immunity to the common contagious pathogens and that there is a delayed response to vaccination. This creates a substantial pool of animals in the shelter that are susceptible to infection once the pathogen is introduced.

Unlike vaccines for CDV, CPV, and FPV, some core vaccines do not induce immunity that prevents infection. The vaccines for FHV, FCV, CPiV, CAV2, and Bordetella bronchiseptica may lessen clinical disease, but do not stop infection and transmission. Add to this picture that there are no vaccines for several common contagious pathogens and the ever-present threat of newly emerging diseases, and it is easy to see why shelters are so vulnerable to disease outbreaks.

While the risk for introduction and spread of disease cannot be eliminated, there are sound and systematic strategies for minimizing the transmission of contagious infections within the shelter.