Module 1: Integration of shelter medical and management teams for a collaborative healthcare program

Estimated Reading and Video Viewing Time: 4 hr

Trained shelter veterinarians have a broad knowledge base and skill set encompassing not just the care of the individual animal, but also the population as a whole. Veterinarians are also trained leaders – they decide the care of patients, oversee their medical staff and operations, and advise on best policies for healthcare. The veterinarian’s medical and leadership skills bring a unique and valuable perspective to the shelter management team. However, many shelter management teams are not aware of the full value of veterinarians outside of performing exams and spay/neuter surgery. Likewise, many veterinarians do not understand the roles and responsibilities of shelter managers. Shelter managers and shelter veterinarians generally have the same high-level goals regarding animal health and welfare, but they too often view shelter policy and operations through conflicting lenses that can create an impasse in communication, expectations, and respect.

This module bridges the gaps in understanding and respecting the different roles of shelter veterinarians and shelter managers and how the medical and management teams can integrate their perspectives to create a collaborative healthcare program.

What are the Roles of the Shelter Veterinarian?

Depends on who you ask… The Association of Shelter Veterinarians defines shelter medicine, the responsibilities of veterinarians in shelters, and why shelters need veterinarians in this statement:

The Association of Shelter Veterinarians believes it is in the best interests of community and animal health for every shelter to have a formal relationship with a veterinarian with direct knowledge of the organization, its population, and its facilities.

Dr. Stephanie Janeczko, Vice President of Shelter Medicine Services for the ASPCA, board-certified in Shelter Medicine, and past President of the Association of Shelter Veterinarians, described shelter medicine practice as “encompassing all aspects of veterinary medicine that are relevant to the management of shelter animal populations, including many skills beyond medical and surgical care. As shelter veterinarians, we must take a broad approach to the physical and behavioral health of the animals that addresses community-level concerns and protects public health. This includes a thorough understanding of epidemiology, immunology, infectious diseases, and animal behavior; educating and managing staff; facilitating spay-neuter and adoption programs; and addressing cases of animal cruelty. “

The shelter veterinarian wears a lot of hats on a daily basis. They must be knowledgeable about proper housing and sanitation, physical health and well-being, enrichment and behavioral health, disease surveillance and epidemiology, management of contagious diseases, protection of public health, investigation of animal cruelty, and surgical procedures other than spay/neuter.

How do shelter managers view the role of shelter veterinarians? In a 2016 survey, researchers distributed an electronic survey to 1,373 managers of animal shelters in North America, to which they received 536 responses. The aims of this survey were to characterize working relationships that shelter personnel have and want with veterinarians, identify opinions that shelter managers have regarding the veterinarians they work with, and determine areas for relationship growth between veterinarians and shelter managers.

“The expectations of shelter managers in this study seemed particularly divergent from those of the expanding field of shelter medicine,” wrote the authors. The study results indicate that the true scope of shelter medicine, and the ability of the shelter veterinarian to improve all shelter healthcare operations, is currently not appreciated by shelter managers, particularly in the area of disease prevention and behavioral health.

Highlights from the Survey of Animal Shelter Managers Regarding Shelter Veterinary Medical Services

- 74% of the responding shelters used local clinics for veterinary care while only 49% had on-site veterinarians.

- Shelter managers indicated interest in increasing the number of veterinarians in the shelter.

- Managers reported that the most important roles and greatest expertise of veterinarians were related to surgery, diagnosis and treatment of individual animals, and providing authorization for purchase and administration of drugs, especially controlled drugs.

- More than 92% of the shelter managers replied that spay/neuter was the most important task performed by their veterinarians.

- Veterinary expertise in disease prevention and behavior was the lowest priority by shelter managers. Yet, every shelter in the study reported a disease problem in their facility and 77% said common shelter infectious diseases had a substantial negative effect on the shelter’s success.

- Shelter managers rated themselves as more knowledgeable than veterinarians about shelter operations, cleaning and disinfection, population management and shelter animal behavior.

We have opinions from the ASV, an experienced shelter veterinarian and shelter medicine leader, and shelter managers about the roles of a shelter veterinarian. Here is the opinion of

Rich Avanzino, widely viewed as the father of the ‘no-kill’ movement and a major influence on companion animal welfare for nearly four decades. Rich was the President of the San Francisco SPCA from 1976 to 1998, Maddie’s Fund President from 1998 to 2015, and now serves as the Strategic Advisor for Maddie’s Fund.

In this opinion piece, Rich discusses the emergence of shelter medicine, the growing demand for shelter medicine education, and the roles of shelter veterinarians in providing policies and protocols for wellness programs, medical and surgical treatments, behavioral programs, disease prevention and management, housing, and cleaning and disinfection.

The most important point in Avanzino’s statement is that “It is no longer acceptable or possible that the education, expertise and talent of veterinarians practicing in shelters be limited to the practice of spay/neuter surgeries. Today’s shelter directors and veterinarians need to work together as a team, with shelter veterinarians being given a policy role consistent with their training and expertise. This is what the veterinary profession expects and what the animals deserve.”

The Standoff

Shelters have operated for many decades without a veterinarian on-site to oversee animal health and welfare. This role has traditionally been left to shelter directors and staff. The field of shelter medicine and careers as shelter veterinarians has emerged over the past 15 years. Having a veterinarian in the shelter is a relatively new relationship that shelter directors and staff are trying to understand and navigate. Likewise, veterinarians are trying to understand their roles and the expectations of the shelter directors and staff.

In general, directors focus on strategic direction and financial viability, while veterinarians are responsible for the health and welfare of shelter and community animals. The differing responsibilities can result in conflicting priorities where veterinarians may prioritize immediate animal care, and directors may prioritize long-term strategies and resource allocation. Managing limited funding and staffing, navigating public expectations, and triaging medical care are just some areas where priority misalignment can occur between veterinarians and directors. Misaligned priorities can hinder collaboration and decision-making.

A 2025 study utilized a survey tool to explore attitudes of 170 shelter veterinarians and directors toward collaboration. The key challenges reported by shelter directors when working with their veterinarian include:

- Managing the vet’s expectations and demands

- Balancing financial constraints with need for quality veterinary care

- Integrating the veterinary goals with overall shelter goals

- Addressing conflicts between veterinary recommendations and shelter priorities

The key challenges reported by shelter veterinarians when working with the director include:

- Lack of effective communication

- Conflicting goals or priorities

- Inadequate recognition or appreciation for the veterinarian’s expertise

- Inadequate support for implementing best practices for health and welfare

- Little involvement in shelter decision-making

Despite divergent attitudes, both shelter directors and shelter vets emphasized constructive communication for fostering successful veterinarian-director relationships where a genuine effort to understand and consider differing perspectives is present. Recognizing the unique viewpoints of veterinarians and integrating their perspectives into decision-making processes can enhance collaborative environments.

Forging this new relationship to work together for collaborative healthcare has not been easy, especially when there is a state of misunderstanding and miscommunication between the shelter medical and management teams. The veterinarians are frustrated by not having more authority and responsibility for the healthcare policies and protocols, their medical staff, and the medical budget. They don’t understand the priorities of the management team and why they make the decisions they do. The management team is frustrated because the veterinarians don’t see the big picture, don’t understand shelter operations, and don’t know local government regulations. They think veterinarians should stay in their lane and stick to exams and surgeries.

The Shelter Director vs. The Shelter Veterinarian

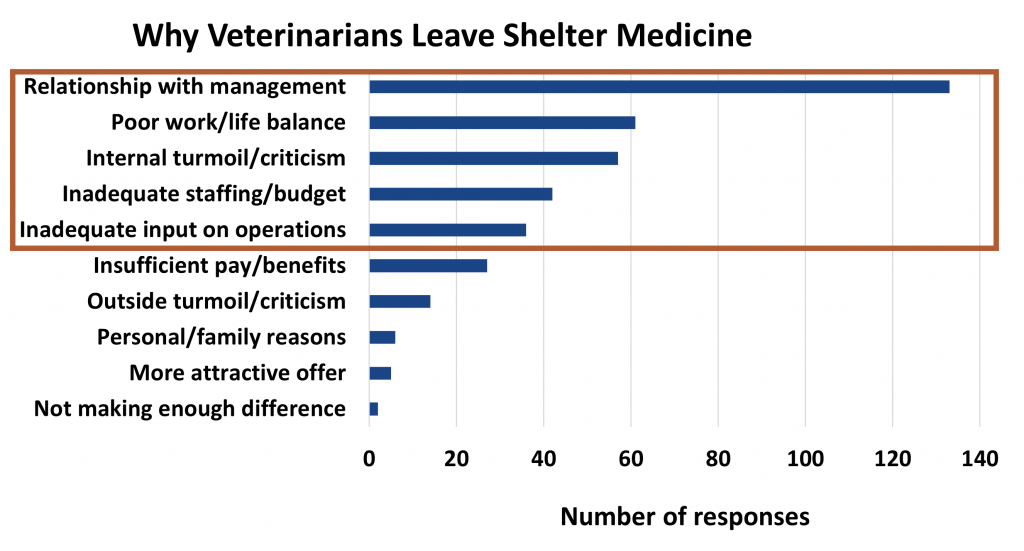

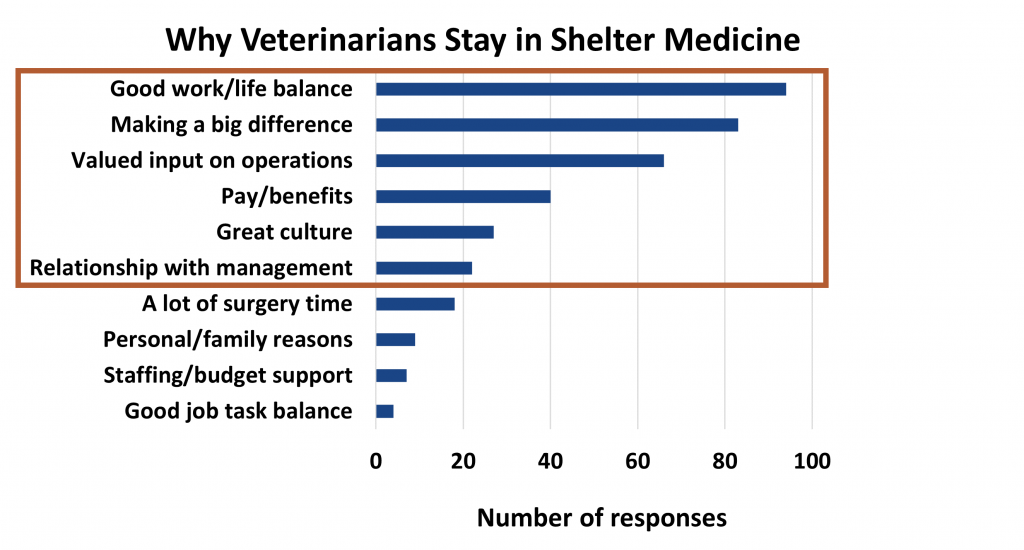

In 2020, the UF Maddie’s Shelter Medicine Program conducted an informal survey of shelter veterinarians in the Shelter Medicine Veterinarians Facebook Group. The survey asked the veterinarians why they stay in shelter practice or why they left shelter practice. Here are the responses from 127 respondents.

Veterinarians leave shelter practice because of a poor or contentious relationship with shelter management, lack of input in shelter operations, poor work/life balance, and inadequate staffing and budget to support good practice.

Shelter veterinarians with good work/life balance, valued input on shelter operations, the feeling of making a big difference, and a good relationship with shelter management stay in shelter practice.

A 2021 study from the University of Pennsylvania Shelter Medicine Program utilized an online survey to probe veterinarians’ perceptions of shelter medicine and their feelings of job satisfaction and the impact on retention in shelter practice. Responses from 91 shelter veterinarians indicated that those that participated in decision-making for patients and shelter management procedures had more job satisfaction and were more inclined to continue working in shelter medicine. The findings also determined that shelter veterinarians leave the field due to poor relationships with management and inadequate input in operations.

In 2022, the Association of Shelter Veterinarians conducted a member survey and virtual townhall to gather feedback on current challenges for shelter veterinarians. One of the important takeaways was that shelter veterinarians want to be included in the shelter leadership team and management decisions. When asked about challenges working with shelter leadership, 51% of the 73 respondents indicated they were having challenges implementing change, and 35% had a contentious relationship with shelter management teams. When asked what would need to change in order for vets to remain in shelter practice, responses included increased involvement with case decisions and shelter operational decisions and improved relationships with management/leadership.

Can shelter veterinarians and shelter managers end the stand-off and work together as a shared leadership team?

Watch This

Watch This

Watch This

Watch This