Chapter 3: Cyberbullying Within the Context of Peers and School

Krista Mehari and Natasha Basu

ABSTRACT

Effective cyberbullying prevention is based on an accurate understanding of risk and protective factors of cyberbullying across systems. Cyberbullying prevention should include individual, relationship, community, and societal factors. Cyberbullying is closely related to in-person bullying and aggression, but it has some unique risk and protective factors also. This chapter conceptualizes cyberbullying as broadly within the umbrella of peer interactions. In this chapter, we describe how other peer interactions and peer relationships can predict the occurrence of cyberbullying and cybervictimization. Similarly, given that youth spend the majority of their time at school, school plays a fundamental role in adolescents’ lives. In this chapter, we also discuss school-level factors that predict or reduce cyberbullying. These factors can be leveraged for school-based prevention. The chapter concludes with the current understanding of effective school-based prevention and school practices in responding to cyberbullying.

As discussed in previous chapters, cyberbullying is perpetrated through electronic communication technologies. Individual, peer, and school factors play an important role in the development of cyberbullying behaviors. Cyberbullying involvement has significant implications for adolescents’ peer and school interactions. Within the context of the socio-ecological model introduced in Chapter 1, peer interactions fall within “relationship” factors, and school factors fall within the “community” level. Cyberbullying happens among peers, so it is important to understand how other peer interactions and peer relationships can predict the occurrence of cyberbullying and cybervictimization. Similarly, understanding school-level factors that predict or reduce cyberbullying is vital for effective intervention.

ASSOCIATIONS BETWEEN CYBERBULLYING INVOLVEMENT AND BULLYING INVOLVEMENT

Cyberbullying and cybervictimization are closely related to in-person bullying and in-person victimization. Many studies have demonstrated strong concurrent relations between cyberbullying and in-person bullying. According to a meta-analysis, in-person bullying is one of the best predictors of cyberbullying. The only stronger correlate of cyberbullying identified in the meta-analysis was cybervictimization.[1] Most of the research on what predicts cyberbullying has been conducted in Western countries.[2]

Research across Asian countries is limited. The available research demonstrates a positive association between in-person bullying and cyberbullying. In a study conducted among adolescents in New Delhi, India, cyberbullying was correlated with indirect or relational bullying but not with physical bullying.[3] In a study conducted with Chinese high school students, in-person bullying was found to be a significant and strong predictor of cyberbullying.[4] Research conducted among South Korean adolescents found a significant positive association between in-person bullying and cyberbullying.[5] Additionally, Kwan and Skoric[6] found strong associations between school bullying and cyberbullying (r = .56) in adolescents from Singapore. In Hong Kong, a study conducted with 1917 adolescents found a positive correlation between in-person bullying and cyberbullying (r = .51).[7] Further, in-person bullying was positively associated with cyberbullying in Cyprus (r = .61).[8]

Based on the existing research in both Western and Asian countries, it is likely that both cyberbullying and in person bullying are types of bullying that manifest through different media. Almost all youth who perpetrate cyberbullying also perpetrate in-person bullying. It is highly uncommon for youth to perpetrate cyberbullying without also having perpetrated in-person bullying. However, it is likely that a smaller percentage of youth who perpetrate in-person bullying also perpetrate cyberbullying.[9],[10],[11] These findings suggest that interventions to reduce in-person bullying may be effective in reducing cyberbullying. However, given that cyberbullying is different from bullying, those interventions may need to be adapted slightly to address the unique aspects of cyberbullying.

Similarly, cybervictimization and in-person victimization are also closely correlated. In the meta-analysis conducted by Kowalski and colleagues,[12] cybervictimization and in-person victimization were correlated at r = .4 indicating a small-to-medium relationship. Again, the only stronger correlate of cybervictimization was cyberbullying.[13] More recent research using behavior-based measures has identified correlations between cybervictimization and in-person victimization as large as .85, indicating a large relationship. Again, most research has been conducted in Western countries.

Emerging research in Asia provides emerging support for the relation between cybervictimization and in-person victimization. For example, a study conducted in Hong Kong found in-person victimization was positively associated with cyberbullying victimization.[14] This relationship was also significant in South Korean adolescents.[15] A positive relationship was demonstrated between in-person victimization and cybervictimization in China (r = .18),[16] Cyprus (r = .48),[17] Japan (r = .32),[18] India (r = .13),[19] Indonesia (r = .73),[20] and Singapore (r = .48).[21] However, one study conducted among middle school students in New Delhi, India did not find a relation between cybervictimization and in-person victimization.[22] However, the majority of the research suggests that cybervictimization and in-person victimization are correlated in Asia. Together, there appears to be a significant association between in-person bullying and cyberbullying across different cultures and countries in Asia.

Based on emerging longitudinal research, it appears that youth are first victimized in person. Youth who are victimized in-person are more likely to experience increases in cybervictimization. For example, it is possible that rumors that are started about an adolescent in person are then spread via text messages or social media. It is also possible that adolescents who victimize a particular adolescent in person begin victimizing that adolescent online in other ways (e.g., making fun of photos, posting rude comments, sending threats). In contrast, youth who are cyber-victimized are not more likely to experience increases in in-person victimization.[23],[24] That is, there is no evidence that victimization that starts online causes an increase in in-person victimization.

ASSOCIATIONS BETWEEN CYBERBULLYING INVOLVEMENT AND INDIVIDUAL FACTORS

A range of individual-level characteristics, such as demographics (e.g., gender, age) and psycho-social factors (such as attitudes and impulsivity) have been explored as possible factors of cyberbullying. These factors can predict why some youth are more likely to be involved in cyberbullying than others.

GENDER DIFFERENCES IN CYBERBULLYING

There is varying evidence about the rates of cyberbullying across gender. Multiple studies have identified higher prevalence of self-reported cyberbullying among male adolescents. This includes a sample adolescents in Australia, Canada, Finland, Taiwan, Turkey, Singapore, and Switzerland.[25],[26],[27],[28],[29],[30] However, several of these studies used the word “bullied” in their measure, which male adolescents may be more willing to endorse because it is less socially undesirable for a boy to admit to bullying than for a girl. Ybarra and Mitchell (2007), who avoided the word “bullied” in their measure, found no gender differences in prevalence of cyberbullying. Still, male adolescents were more likely to be frequent aggressors.[31] On the other hand, Calvete and colleagues (2010) found that there were no gender differences in frequency of perpetration overall, but that male adolescents were more likely to send sexual messages and to post videos of assaults.[32]

No gender differences in perpetration of cyberbullying were found in a number of studies in Canada. These studies included ethnically diverse samples of adolescents in Europe, the United States, and online.[33],[34],[35],[36],[37],[38],[39],[40],[41],[42] Overall, findings indicate that there are no gender differences. If gender differences exist, male adolescents are slightly more likely to self-report perpetration of cyberbullying. Despite these findings, researchers continue to argue that female adolescents prefer indirect and relational forms of aggression that are easily perpetrated through electronic means.[43] This is not supported, and in fact often contradicted, by research.

Gender differences in cyberbullying in Asian countries and specifically in India have yet to be fully explored. One study of 11-15-year-old students in the Delhi area found that male adolescents reported higher prevalence of cybervictimization. There were no gender differences in cyberbullying perpetration.[44] In general, existing surveillance data suggest that male adolescents have greater access to electronic communication devices than female adolescents in India, especially in rural areas.[45] It is possible that male adolescents may be more likely to have cyberbullying involvement simply due to access. More research is needed to explore whether there are gender differences in cyberbullying involvement in India.

AGE DIFFERENCES IN CYBERBULLYING ACROSS ADOLESCENCE

In addition to gender differences, several studies have explored age differences in cyberbullying across adolescence. There is some evidence that cyberbullying peaks in early adolescence (11-14 years old) and decreases in later adolescence (15 years old and older). This finding is comparable to the trajectory observed in in-person bullying. This broad pattern has been found in the U.S. and Canada.[46],[47],[48] It is possible that as adolescents enter secondary schools (e.g., middle school, junior high, high school) where they are first exposed to cyberbullying. Then they begin to perpetrate cyberbullying due to observational learning and perhaps reactive aggression. It is unclear whether this pattern is comparable in other countries, especially in lower or middle-income countries, where private access to electronic communication devices might be less common in early adolescence.

PSYCHO-SOCIAL RISK FACTORS FOR CYBERBULLYING INVOLVEMENT

Most research on individual-level factors associated with cyberbullying involvement has been cross-sectional. That is, the hypothesized “risk” factors are assessed at the same time point as the outcome (cyberbullying involvement). Therefore, it is impossible to determine whether these factors cause cyberbullying, whether cyberbullying causes those other factors, or whether something else (something that was not assessed) causes both cyberbullying involvement and the other factors. Because of this, at most, we can assume that these factors co-occur with cyberbullying involvement.

Psycho-social characteristics that may place adolescents at risk for cyberbullying perpetration include low levels of empathy, moral disengagement, beliefs supporting aggression, impulsivity, other delinquent behavior, and substance use.[49],[50],[51],[52],[53],[54] In addition, adolescents who use the Internet more frequently and engage in more risky online behaviors (e.g., sharing personal information, agreeing to meet in person with someone they met online) are more likely to perpetrate cyberbullying.[55] Patterns of Internet usage also predict other digital risks such as online sexual solicitations and sexual risk behaviors, exposure to a variety of explicit content, and information breaches and privacy violations. This is explained in further detail in Chapter 5 of this book.

Similar to cyberbullying perpetration, psycho-social characteristics that place adolescents at risk for cybervictimization include low levels of empathy, beliefs supporting aggression, lower social intelligence and social anxiety, lower academic achievement, substance use, and loneliness.[56] As with cyberbullying perpetration, adolescents who spend more time on the Internet and engage in more risky online behaviors are more likely to be victimized.[57],[58] It is important to note that most of the research on psycho-social predictors of cyberbullying involvement was conducted in Western and high-income countries. It is unclear whether risks for cyberbullying perpetration would be the same or different in Asian countries and lower- to middle-income countries. Because of this, more research is needed to understand what individual-level factors may explain individual differences in cyberbullying involvement among youth in Asian countries.

ASSOCIATIONS BETWEEN CYBERBULLYING INVOLVEMENT AND PEER FACTORS

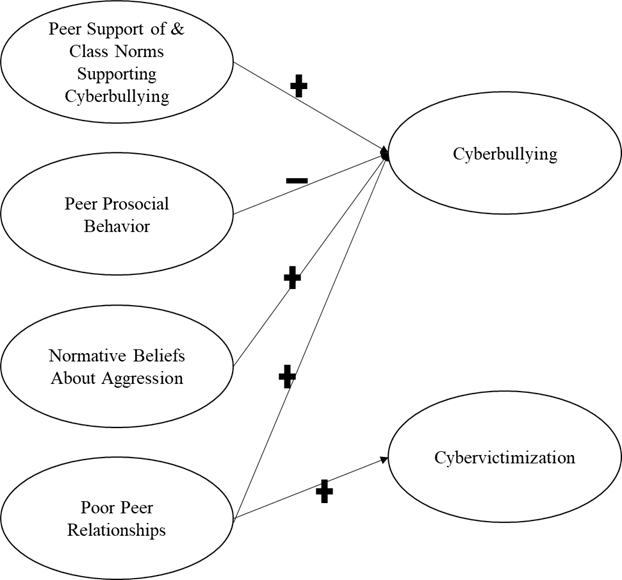

Peer factors fall within the “relationship” domain of the socio-ecological model. Like individual-level factors, they explain a significant percentage of differences in youths’ levels of cyberbullying involvement. Broadly, peer attitudes supporting bullying or cyberbullying predict individual youths’ levels of bullying and cyberbullying perpetration.[59] This may be due to social mimicry. Specifically, peers who support cyberbullying may be more likely to model cyberbullying behaviors. This may cause increased cyberbullying due to increased exposure to aggressive peer models.[60] In addition, when adolescents do try out aggressive behaviors, they are likely to be reinforced by their peers if their peers have attitudes justifying cyberbullying perpetration. For example, when adolescents believe their peers support and approve of cyberbullying, they are more likely to take online risks like cyberbullying.[61] Adolescents who have pro-social peers have lower levels of cyberbullying.

In a peer group that supports aggression, using aggression may provide adolescents with power, status, and privilege among their peers. This finding is consistent with a research study conducted with adolescents from Singapore and Malaysia, whose ethnic identification included Chinese, Malay, and Indian. It found a positive association between cyberbullying and normative beliefs about aggression.[62] Reinforcement by friends was found to be positively associated with cyberbullying in Japan.[63] This finding is supported by a qualitative study in Indonesia which demonstrated that group conformity facilitated an increase in the prevalence of cyberbullying among adolescents.[64] Finally, a study in China found that pro-cyberbullying class norms predicted the occurrence of cyberbullying in high school.[65] Interestingly, this was only true when students perceived their class to be highly cohesive. In contrast, when a high school student perceived their class to have low cohesion, there was not a significant relationship between pro-cyberbullying class norms and incidents of cyberbullying.[66] This study demonstrated one possible mechanism for why these normative beliefs might vary across groups.

Popularity and social acceptance may play an interesting role in cyberbullying. One study of adolescents in the western United States found that both cyberbullying and cybervictimization were positively associated with popularity and social acceptance cross-sectionally. In addition, popularity predicted increases in cyberbullying, whereas cyberbullying predicted increases in popularity for girls but decreases in popularity for boys. Social acceptance predicted increased cyberbullying for boys but not for girls.[67] In a sample of students in secondary schools in Germany, cybervictimization during chat sessions was negatively associated with self-reported perceived popularity with other chatters.[68] In a sample of elementary school children in a predominantly white, upper SES school in the United States, cyberbullying perpetration was concurrently associated with lower popularity and social acceptance. Both popularity and social acceptance were measured by peer report. Similarly, cyberbullying was associated with fewer mutual friendships.[69] Currently, the majority of the research on popularity, social acceptance, and cyberbullying is conducted in Europe and North America. As such, there is no research on the generalizability of these relationships in Asian countries.

The relation between peer rejection and cyberbullying is complex. In a study of middle school students in the midwestern United States, peer rejection was concurrently correlated with relational and verbal cyberbullying. It also predicted increases in cyberbullying.[70] Cyberbullying was also linked to loneliness in a sample of elementary school children in the United States.[71] Research conducted in Asia also suggests that cyberbullying involvement is associated with poor peer relationships. For example, a study of Chinese middle school students found a positive association between cyberbullying and loneliness.[72] Similarly, another cross-sectional study of Chinese middle school students reported better peer relationships were negatively associated with engagement in cyberbullying.[73] Cross-national research conducted with adolescents living in China, India, and Japan found that peer attachment was negatively associated with cyberbullying perpetration in China and India, but not in Japan. Additionally, within China, India, and Japan, adolescents who were not involved in cyberbullying had greater peer attachment compared to youth with any involvement in cyberbullying (victimization, perpetration, or some combination of those).[74]

It is possible that peer rejection and aggression are part of a vicious cycle. In this cycle, children who are aggressive in a non-socially skilled way are more likely to be rejected. Children may react to rejection with increased aggression. It is also possible that adolescents engage in cyberbullying as a way to establish their social position and to attempt to maintain their social status. However, it is possible that the skill level of adolescents varies widely. This means that cyberbullying may promote the social status of socially skilled youth, but that it may harm the social status of socially awkward youth. It is also possible that cyberbullying is less reinforced than in-person bullying. Thus, is less likely to promote social dominance, than in-person bullying[75] because of the asynchronicity of interactions during online communications. That is, an adolescent could post a mocking picture of a peer, but not know or notice when it was shared, laughed at, or commented on. It is also possible that fewer peers in the same social circles would know about the post than if it happened in person at school, where youth spend the majority of their time together.

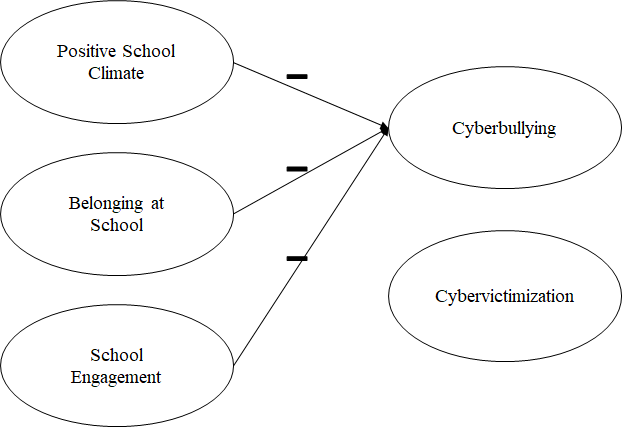

ASSOCIATIONS BETWEEN CYBERBULLYING INVOLVEMENT AND SCHOOL FACTORS

School factors fall within the “community” level of the socio-ecological model. Like individual and relationship level factors, school factors explain a small but significant amount of individual differences in cyberbullying. Although schools are often on the front lines of confronting cyberbullying behaviors (Pelfrey et al., 2015), little is known about the associations between school factors and cyberbullying involvement. It is important to note that cyberbullying appears to have higher rates of perpetration during out-of-school time compared to during school hours (e.g., Smith et al., 2008). Therefore, although supervision and restriction may reduce cyberbullying during the school day, it may not help in prevention of all acts of cyberbullying. Other factors related to school climate, including fostering a positive climate and promoting healthy relationships, may be more important. In a meta-analysis of research mostly conducted in Western countries, school climate and school safety had small but significant correlations with lower rates of cyberbullying perpetration and victimization (Kowalski et al., 2014). That is, adolescents in schools that they perceived to be safe, with positive student-student and student-teacher relationships, were less likely both to perpetrate cyberbullying and experience cybervictimization. In school environments, close relationships with teachers are associated with reduced likelihood of bullying and cyberbullying.[76] Teachers’ awareness of cyberbullying and intervention has also been related to lower rates cyberbullying.[77] At an individual level, youth who are involved in cyberbullying may have more problems at school than youth who are not involved in cyberbullying, such as getting in trouble and not feeling safe at school.[78],[79]

School risk factors for cyberbullying involvement is an emerging body of research in Asian countries. Wang and colleagues (2019) found in a study conducted in China that adolescents who perceived a more positive school climate were less likely to perpetrate cyberbullying.[80] Further, in a study of Hong Kong youth, a sense of belonging at school was associated with lower levels of cyberbullying perpetration.[81] A more recent study in Hong Kong found different relations between school factors and cyberbullying for male and female students.[82] For male adolescents, positive school experiences and school involvement were negatively associated with cyberbullying perpetration. For female adolescents, a sense of belonging in school was negatively associated with cyberbullying perpetration.[83] Together, these studies underscore the importance of considering school influences to understand developmental processes that lead to cyberbullying.

SCHOOL-BASED PREVENTION PROGRAMS

Schools can be an ideal setting for prevention efforts due to their reach. The heavy majority of youth attend school. Because of this, schools have a golden opportunity to promote the safety, health, well-being, and citizenship of the majority of youth in a country. School-based prevention strategies include primary prevention (strategies to prevent cyberbullying before it begins) and secondary prevention (strategies to reduce the frequency of cyberbullying or mitigate the impact of cyberbullying). A combination of the two strategies is important for a holistic prevention approach. In addition to specific prevention programs, schools can create policies that may serve as primary and secondary prevention strategies. There can be two approaches to these prevention strategies: a punitive, fear-based approach, or a resilience-based approach. A fear-based approach includes heavy restrictions of digital media, zero-tolerance policies, and punishment for undesired behavior without training, modeling, scaffolding of, and reinforcement of desired behavior. In contrast, a resilience-based approach focuses on creating a positive school climate; training, modeling, and reinforcing desired behaviors. It also focuses on building capacity in adult stakeholders to prevent and intervene in cyberbullying. Further it focuses on providing remedial skill-building for youth who engage in cyberbullying.

PRIMARY PREVENTION

Existing reviews of cyberbullying prevention programs suggest that most cyberbullying prevention programs are school-based and show promise of effectiveness.[84],[85],[86] However, in general, individual programs have only been supported by a single research study conducted by the program developers.[87] More research is needed to identify the active ingredients for effective school-based cyberbullying prevention programs. Due to the high degree of overlap between cyberbullying and in-person bullying, many of the skills taught in school-based violence or bullying prevention programs are likely to be relevant to the reduction of cyberbullying. Such programs may include anger management, empathy, and problem-solving.

However, because of the differences in circumstances surrounding in-person and electronic communication, those programs may need to be adapted or include cyberbullying-specific modules. For example, teaching adolescents to read facial expressions or other physical cues will not improve empathy in situations where the other person’s facial expressions are not visible. In that case, teaching perspective-taking based on identifying the situation and thinking about how people might feel when they were in that situation may help to improve empathy in electronic communications. Beliefs about aggression are also particularly relevant to aggressive behaviors and may be different for cyberbullying. There is some emerging evidence to support this.[88] Intervention programs may need to target cyberbullying-specific beliefs. It is possible that adolescents perceive the social context for electronic aggression to be less disapproving than for in-person aggression. Initial focus group data also suggests that adults in India may be more tolerant of cyberbullying than of physical bullying. This may cause youth to believe that they may not have effective advocates in the adults close to them.[89] Because of this, school-based efforts may need to include education for parents and guardians on cyberbullying, its impact, and its prevention. In addition, for both youth and adults, digital safety behaviors, including protection of private information, should be taught as part of intervention programs.[90],[91] A more comprehensive description of digital safety is provided in Chapter 5.

Promoting a positive school climate and positive peer relationships may also help to reduce cyberbullying. Adolescents are unlikely to tell their parents about victimization experiences, and even more unlikely to tell teachers.[92],[93],[94],[95] On the other hand, as much as 75% of victimized adolescents will tell their friends.[96] Friendship is a strong resource for adolescents. It has been shown to mitigate the effects of victimization as well as to reduce the likelihood of victimization occurring in the future.[97] Because of this, interventions could also teach adolescents how they can best help their friends when they know that their friends are perpetrating cyberbullying, being cyber-victimized, or both.

PRIMARY PREVENTION: SCHOOL-LEVEL POLICY

Currently, many schools do not have policies and procedures around appropriate and safe behavior online. There is an urgent need for schools to establish and promulgate expectations for digital behavior and to identify procedures for when those expectations are not met.[98] Clear expectation-setting prior to problematic behavior can often reduce the occurrence of problematic behaviors. These policies should include identification and reinforcement of pro-social behavior both online and in-person. An example of an intervention based on clear expectation-setting and reinforcement of desired behaviors is School-Wide Positive Behavior Support (SWPBS). SWPBS is a widely-used, whole-school behavior support program that focuses on establishing clear behavior expectations for students. It also focuses on consistently reinforcing desired behavior across school settings, and identifying and implementing a range of consequences for problem behaviors.[99] Such school-level strategies can be helpful in preventing cyberbullying before it becomes a problem.

SECONDARY PREVENTION: SCHOOL RESPONSES TO CYBERBULLYING INCIDENTS

Even if the most effective primary prevention strategies are implemented, it is likely that some cyberbullying will occur. This creates a need to establish procedures to respond to cyberbullying. Cyberbullying is unusual in that it does not occur in a physical space. This raises the question of whose responsibility it is to monitor electronic interactions and enforce consequences for adolescents who are perpetrating cyberbullying. Most researchers have pointed to the schools as the primary responsible authority. Despite most cyberbullying occurring outside of school property, schools have an ethical and legal responsibility to intervene when cyberbullying creates an unsafe environment that impedes students’ ability to learn.[100] Schools are placed in a difficult position. On one hand, they may not violate students’ freedom of speech in countries that protect freedom of speech, particularly when that speech is occurring off school grounds. On the other hand, the school is required to provide a safe learning environment with equal access to education. A school is liable in the United States if it has “effectively caused, encouraged, accepted, tolerated, or failed to correct” a hostile environment that impairs a student’s ability to learn (p. S65).[101] Because of schools’ somewhat vague position as monitor and enforcer, it is also important for parents and guardians to be involved. Schools are only responsible to intervene when they are aware of the situation and can demonstrate that the situation is interfering in the learning process in some way. Parents and guardians can advocate for changes in school policy and government regulations, as well as draw media attention to areas of concern.[102] Parents and guardians can also monitor their children’s digital behavior, teach and model respectful interactions, and intervene if their child is aggressive or victimized.

As schools craft policies related to cyberbullying and digital behavior, there are important issues to keep in mind:

- Youth who are victimized should not be responsible for investigating or proving the incident. Before the aggressor is identified and the wrongful nature of the act is established, it is important that the person who reported the aggression (bystander, victim, or parent) does not bear the burden of proving what happened and who did it. It is an unfortunate effect of “innocent until proven guilty” that the victims or reporters are wrong until they prove themselves right. This approach decreases the likelihood that adolescents will put themselves through that painful process. One way to circumvent this unintentional punishment is to establish a school staff member to receive complaints, anonymously if desired, and to investigate the incident. Then, if aggression is established, the steps outlined in school policy must be followed. This will remove the burden of proof from reporters, thus teaching reporters that they will not be punished for seeking help. It will also teach adolescents who are perpetrating aggression that their behavior will be detected and addressed. The process of implementing clear, just school policies and procedures may change the dynamics from a conflict between the aggressor and the reporter (likely the victim) into an established procedure in which school officials take action against a violation of school policy.

- Restriction of victimized youths’ access to electronic media may be punitive and unhelpful. Encouraging adolescents who have been victimized to simply reduce their electronic interactions (e.g., taking down personal pages on social networking sites, or not going online at all) may be the first intervention response that comes to mind for adults. However, fear of online restriction is one of the primary reasons that adolescents do not tell adults about their victimization experiences. It is important to understand that adolescents consider reduced access to communication technologies to be a punishment.[103],[104] It may be productive to encourage communication between adolescents and their teachers. But before this is done, adolescents must first know that reporting will both resolve the problem and not result in negative outcomes for themselves.

- Abusing youth who perpetrate cyberbullying is not effective in changing behavior. It is important not to place all the blame on adolescents who cyberbully. As shown by the high correlation between cyberbullying and cybervictimization, there are often no purely provocative adolescents or blameless victims. Adolescents learn negative patterns of interactions through modeling and reinforcement. They are often impulsive and misinterpret cues. Sometimes they may simply have difficulty taking the other person’s perspective into account or understanding the damage caused by their actions. In addition, there are currently few clear rules or expectations regarding electronic behavior, which may feed into a perception that aggressive behavior is not a problem and will not be punished. Anticipation of blame also reduces adolescents’ likelihood to report their experiences when victimized, because they believe that the only negative consequences will be for themselves (Mishna et al., 2009). The consequences for aggressive adolescents should be aversive but should also help them to identify pro-social strategies for reaching goals, managing anger, controlling impulsivity, and resolving conflict. Doing this will avoid abusing adolescents who likely have been victimized themselves while promoting a healthy and respectful electronic culture. Specific ways to accomplish these goals may include anger management or perspective-taking training.

- Most policy changes have not been empirically tested. Currently, the best-practice recommendations for school policy are based on descriptive research and anecdotal evidence. To address these issues, creating, implementing, and evaluating policies and procedures for cyberbullying involvement is vital (Hertz & David-Ferdon, 2008).

The following chapters discuss how to avoid cyberbullying and to some extent how to effectively deal with cyberbullying. Chapter four addresses parents’ and caregivers’ needs for guidance and reassurance on how best maintain their children’s safety online and protect against cyberbullying. We emphasize the importance of parent-child communication, warm parent-child relationships, and parental monitoring that supports adolescents’ search for autonomy. In short, this chapter details the role of family, especially parental relationships and media parenting with respect to cyberbullying behavior among youth.

CONCLUSION

Cyberbullying and cybervictimization are closely related to in-person bullying and victimization. Because we know that a range of individual psychosocial factors, relationship factors, and community factors predict cyberbullying, intervention strategies should not just target individual youth, but should also target peer groups and schools. Schools have the potential to play an important role in cyberbullying prevention. It is important to use the existing research on cyberbullying prevention and bullying prevention so that we can make sure that we are investing our resources in prevention strategies that keep youth safe online.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Peer and school factors predict perpetration of cyberbullying.

- Best practice cyberbullying prevention strategies should promote healthy relationship, emotion regulation, and problem-solving skills, as well as digital safety and citizenship.

- Effective prevention and intervention must include school-level policies and procedures that promote a positive school climate, create clear expectations for appropriate behavior, and identify resilience-based strategies to respond to cyberbullying incidents.

- Both school policy and prevention programs must be evaluated and modified to be maximally effective.

- Kowalski RM, Giumetti GW, Schroeder AN, Lattanner MR. Bullying in the digital age: A critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychological Bulletin 2014;140(4):1073-1073-1137. ↵

- Farrell AD, Thompson EL, Mehari KR, Sullivan TN, Goncy EA. Assessment of in-person and cyber aggression and victimization, substance use, and delinquent behavior during early adolescence. Assessment 2020;27(6):1213-1229. ↵

- Sharma D, Kishore J, Sharma N, Duggal M. Aggression in schools: cyberbullying and gender issues. Asian journal of psychiatry 2017;29:142-145. ↵

- Li Q. Bullying in the new playground: Research into cyberbullying and cyber victimisation. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 2007;23(4). ↵

- Hong JS, Kim DH, Thornberg R, Kang JH, Morgan JT. Correlates of direct and indirect forms of cyberbullying victimization involving South Korean adolescents: An ecological perspective. Comput Hum Behav 2018;87:327-336. ↵

- Kwan GCE, Skoric MM. Facebook bullying: An extension of battles in school. Comput Hum Behav 2013;29(1):16-25. ↵

- Wong DS, Chan HCO, Cheng CH. Cyberbullying perpetration and victimization among adolescents in Hong Kong. Children and youth services review 2014;36:133-140. ↵

- Solomontos-Kountouri O, Tsagkaridis K, Gradinger P, Strohmeier D. Academic, socio-emotional and demographic characteristics of adolescents involved in traditional bullying, cyberbullying, or both: Looking at variables and persons. International Journal of Developmental Science 2017;11(1-2):19-30. ↵

- Raskauskas J, Stoltz AD. Involvement in traditional and electronic bullying among adolescents. Dev Psychol 2007;43(3):564. ↵

- Kowalski RM, Morgan CA, Limber SP. Traditional bullying as a potential warning sign of cyberbullying. School Psychology International 2012;33(5):505-519. ↵

- Smith PK, Mahdavi J, Carvalho M, Fisher S, Russell S, Tippett N. Cyberbullying: Its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry 2008;49(4):376-385. ↵

- Kowalski RM, Giumetti GW, Schroeder AN, Lattanner MR. Bullying in the digital age: A critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychological Bulletin 2014;140(4):1073-1073-1137. ↵

- Kowalski RM, Giumetti GW, Schroeder AN, Lattanner MR. Bullying in the digital age: A critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychological Bulletin 2014;140(4):1073-1073-1137. ↵

- Wong DS, Chan HCO, Cheng CH. Cyberbullying perpetration and victimization among adolescents in Hong Kong. Children and youth services review 2014;36:133-140. ↵

- Hong JS, Kim DH, Thornberg R, Kang JH, Morgan JT. Correlates of direct and indirect forms of cyberbullying victimization involving South Korean adolescents: An ecological perspective. Comput Hum Behav 2018;87:327-336. ↵

- Wright MF, Aoyama I, Kamble SV, Li Z, Soudi S, Lei L, et al. Peer attachment and cyber aggression involvement among Chinese, Indian, and Japanese adolescents. Societies 2015;5(2):339-353. ↵

- Solomontos-Kountouri O, Tsagkaridis K, Gradinger P, Strohmeier D. Academic, socio-emotional and demographic characteristics of adolescents involved in traditional bullying, cyberbullying, or both: Looking at variables and persons. International Journal of Developmental Science 2017;11(1-2):19-30. ↵

- Wright MF, Aoyama I, Kamble SV, Li Z, Soudi S, Lei L, et al. Peer attachment and cyber aggression involvement among Chinese, Indian, and Japanese adolescents. Societies 2015;5(2):339-353. ↵

- Wright MF, Aoyama I, Kamble SV, Li Z, Soudi S, Lei L, et al. Peer attachment and cyber aggression involvement among Chinese, Indian, and Japanese adolescents. Societies 2015;5(2):339-353. ↵

- Safaria T. Prevalence and impact of cyberbullying in a sample of indonesian junior high school students. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology-TOJET 2016;15(1):82-91. ↵

- Kwan GCE, Skoric MM. Facebook bullying: An extension of battles in school. Comput Hum Behav 2013;29(1):16-25. ↵

- Sharma D, Kishore J, Sharma N, Duggal M. Aggression in schools: cyberbullying and gender issues. Asian journal of psychiatry 2017;29:142-145. ↵

- Jose PE, Kljakovic M, Scheib E, Notter O. The joint development of traditional bullying and victimization with cyber bullying and victimization in adolescence. J Res Adolesc 2012;22(2):301-309. ↵

- Mehari KR, Thompson EL, Farrell AD. Differential longitudinal outcomes of in-person and cyber victimization in early adolescence. Psychology of violence 2020;10(4):367. ↵

- i Q. Cyberbullying in schools: A research of gender differences. School psychology international 2006;27(2):157-170. ↵

- Huang Y, Chou C. An analysis of multiple factors of cyberbullying among junior high school students in Taiwan. Comput Hum Behav 2010;26(6):1581-1590. ↵

- Aricak T, Siyahhan S, Uzunhasanoglu A, Saribeyoglu S, Ciplak S, Yilmaz N, et al. Cyberbullying among Turkish adolescents. Cyberpsychology & behavior 2008;11(3):253-261. ↵

- Ang RP, Goh DH. Cyberbullying among adolescents: The role of affective and cognitive empathy, and gender. Child Psychiatry & Human Development 2010;41(4):387-397. ↵

- Sourander A, Brunstein Klomek A, Ikonen M,et al. Psychosocial risk factors associated with cyberbullying among adolescents: A population-based study. Archives of General Psychiatry 2010 July 1;67(7):720-728. ↵

- Perren S, Dooley J, Shaw T, Cross D. Bullying in school and cyberspace: Associations with depressive symptoms in Swiss and Australian adolescents. Child and adolescent psychiatry and mental health 2010;4(1):1-10. ↵

- Ybarra ML, Mitchell KJ. Prevalence and frequency of Internet harassment instigation: Implications for adolescent health. Journal of Adolescent Health 2007;41(2):189-195. ↵

- Calvete E, Orue I, Estévez A, Villardón L, Padilla P. Cyberbullying in adolescents: Modalities and aggressors’ profile. Comput Hum Behav 2010;26(5):1128-1135. ↵

- Li Q. Bullying in the new playground: Research into cyberbullying and cyber victimisation. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 2007;23(4). ↵

- Smith PK, Mahdavi J, Carvalho M, Fisher S, Russell S, Tippett N. Cyberbullying: Its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry 2008;49(4):376-385. ↵

- Slonje R, Smith PK, Frisén A. The nature of cyberbullying, and strategies for prevention. Comput Hum Behav 2013;29(1):26-32. ↵

- Beran T, Li Q. Cyber-harassment: A study of a new method for an old behavior. Journal of educational computing research 2005;32(3):265. ↵

- Kowalski RM, Limber SP. Electronic bullying among middle school students. Journal of adolescent health 2007;41(6):S22-S30. ↵

- Sontag LM, Graber JA, Clemans KH. The role of peer stress and pubertal timing on symptoms of psychopathology during early adolescence. Journal of youth and adolescence 2011;40(10):1371-1382. ↵

- Werner NE. Do Hostile Attribution Biases in Children and Parents Predict Relationally Aggressive Behavior? The Journal of genetic psychology 07/2012;173(3):221; 221-245; 245. ↵

- Wade A, Beran T. Cyberbullying: The new era of bullying. Canadian Journal of School Psychology 2011;26(1):44-61. ↵

- Bauman S. Cyberbullying in a rural intermediate school: An exploratory study. The Journal of Early Adolescence 2010;30(6):803-833. ↵

- Hinduja S, Patchin JW. Cyberbullying: An exploratory analysis of factors related to offending and victimization. Deviant Behav 2008;29(2):129-156. ↵

- Huang Y, Chou C. An analysis of multiple factors of cyberbullying among junior high school students in Taiwan. Comput Hum Behav 2010;26(6):1581-1590. ↵

- Sharma D, Kishore J, Sharma N, Duggal M. Aggression in schools: cyberbullying and gender issues. Asian journal of psychiatry 2017;29:142-145. ↵

- UNICEF. Child online protection in India. 2017. ↵

- Kowalski RM, Limber SP. Electronic bullying among middle school students. Journal of adolescent health 2007;41(6):S22-S30. ↵

- Wade A, Beran T. Cyberbullying: The new era of bullying. Canadian Journal of School Psychology 2011;26(1):44-61. ↵

- Bauman S. Cyberbullying in a rural intermediate school: An exploratory study. The Journal of Early Adolescence 2010;30(6):803-833. ↵

- Kowalski RM, Giumetti GW, Schroeder AN, Lattanner MR. Bullying in the digital age: A critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychological Bulletin 2014;140(4):1073-1073-1137. ↵

- Ang RP, Goh DH. Cyberbullying among adolescents: The role of affective and cognitive empathy, and gender. Child Psychiatry & Human Development 2010;41(4):387-397. ↵

- Sourander A, Brunstein Klomek A, Ikonen M,et al. Psychosocial risk factors associated with cyberbullying among adolescents: A population-based study. Archives of General Psychiatry 2010 July 1;67(7):720-728. ↵

- Calvete E, Orue I, Estévez A, Villardón L, Padilla P. Cyberbullying in adolescents: Modalities and aggressors’ profile. Comput Hum Behav 2010;26(5):1128-1135. ↵

- Sontag LM, Graber JA, Clemans KH. The role of peer stress and pubertal timing on symptoms of psychopathology during early adolescence. Journal of youth and adolescence 2011;40(10):1371-1382. ↵

- Bauman S. Cyberbullying in a rural intermediate school: An exploratory study. The Journal of Early Adolescence 2010;30(6):803-833. ↵

- Kowalski RM, Giumetti GW, Schroeder AN, Lattanner MR. Bullying in the digital age: A critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychological Bulletin 2014;140(4):1073-1073-1137. ↵

- Kowalski RM, Giumetti GW, Schroeder AN, Lattanner MR. Bullying in the digital age: A critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychological Bulletin 2014;140(4):1073-1073-1137. ↵

- Navarro R, Serna C, Martínez V, Ruiz-Oliva R. The role of Internet use and parental mediation on cyberbullying victimization among Spanish children from rural public schools. European journal of psychology of education 2013;28(3):725-745. ↵

- Casas JA, Del Rey R, Ortega-Ruiz R. Bullying and cyberbullying: Convergent and divergent predictor variables. Comput Hum Behav 2013;29(3):580-587. ↵

- Elledge LC, Williford A, Boulton AJ, DePaolis KJ, Little TD, Salmivalli C. Individual and contextual predictors of cyberbullying: The influence of children’s provictim attitudes and teachers’ ability to intervene. Journal of youth and adolescence 2013;42(5):698-710. ↵

- Moffitt TE. Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: a developmental taxonomy. Psychol Rev 1993;100(4):674. ↵

- Sasson H, Mesch G. Parental mediation, peer norms and risky online behavior among adolescents. Comput Hum Behav 2014;33:32-38. ↵

- Ang RP, Tan K, Talib Mansor A. Normative beliefs about aggression as a mediator of narcissistic exploitativeness and cyberbullying. J Interpers Violence 2011;26(13):2619-2634. ↵

- Barlett CP, Gentile DA, Anderson CA, Suzuki K, Sakamoto A, Yamaoka A, et al. Cross-cultural differences in cyberbullying behavior: A short-term longitudinal study. Journal of cross-cultural psychology 2014;45(2):300-313. ↵

- Rahmawati R. Cyberbullying Behavior among Teens Moslem in Pekalongan Indonesia. Proceedings of Universiti Sains Malaysia 2015;238. ↵

- Dang J, Liu L. When peer norms work? Coherent groups facilitate normative influences on cyber aggression. Aggressive Behav 2020;46(6):559-569. ↵

- Dang J, Liu L. When peer norms work? Coherent groups facilitate normative influences on cyber aggression. Aggressive Behav 2020;46(6):559-569. ↵

- Badaly D, Kelly BM, Schwartz D, Dabney-Lieras K. Longitudinal associations of electronic aggression and victimization with social standing during adolescence. Journal of youth and adolescence 2013;42(6):891-904. ↵

- Katzer C, Fetchenhauer D, Belschak F. Cyberbullying: Who are the victims? A comparison of victimization in Internet chatrooms and victimization in school. Journal of media Psychology 2009;21(1):25-36. ↵

- Schoffstall CL, Cohen R. Cyber aggression: The relation between online offenders and offline social competence. Social Development 2011;20(3):587-604. ↵

- Wright MF, Li Y. The association between cyber victimization and subsequent cyber aggression: The moderating effect of peer rejection. Journal of youth and adolescence 2013;42(5):662-674. ↵

- Schoffstall CL, Cohen R. Cyber aggression: The relation between online offenders and offline social competence. Social Development 2011;20(3):587-604. ↵

- Jiang Q, Zhao F, Xie X, Wang X, Nie J, Lei L, et al. Difficulties in emotion regulation and cyberbullying among Chinese adolescents: a mediation model of loneliness and depression. J Interpers Violence 2020:0886260520917517. ↵

- Wang P, Wang X, Lei L. Gender differences between student–student relationship and cyberbullying perpetration: An evolutionary perspective. J Interpers Violence 2019:0886260519865970. ↵

- Wright MF, Aoyama I, Kamble SV, Li Z, Soudi S, Lei L, et al. Peer attachment and cyber aggression involvement among Chinese, Indian, and Japanese adolescents. Societies 2015;5(2):339-353. ↵

- Salmivalli C, Sainio M, Hodges EV. Electronic victimization: Correlates, antecedents, and consequences among elementary and middle school students. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology 2013;42(4):442-453. ↵

- Doty JL, Gower AL, Sieving RE, Plowman SL, McMorris BJ. Cyberbullying victimization and perpetration, connectedness, and monitoring of online activities: Protection from parental figures. Social Sciences 2018;7(12):265. ↵

- Elledge LC, Williford A, Boulton AJ, DePaolis KJ, Little TD, Salmivalli C. Individual and contextual predictors of cyberbullying: The influence of children’s provictim attitudes and teachers’ ability to intervene. Journal of youth and adolescence 2013;42(5):698-710. ↵

- Sourander A, Brunstein Klomek A, Ikonen M,et al. Psychosocial risk factors associated with cyberbullying among adolescents: A population-based study. Archives of General Psychiatry 2010 July 1;67(7):720-728. ↵

- Hinduja S, Patchin JW. Cyberbullying: An exploratory analysis of factors related to offending and victimization. Deviant Behav 2008;29(2):129-156. ↵

- Wang P, Wang X, Lei L. Gender differences between student–student relationship and cyberbullying perpetration: An evolutionary perspective. J Interpers Violence 2019:0886260519865970. ↵

- Wong DS, Chan HCO, Cheng CH. Cyberbullying perpetration and victimization among adolescents in Hong Kong. Children and youth services review 2014;36:133-140. ↵

- Chan HC, Wong DS. Traditional school bullying and cyberbullying perpetration: Examining the psychosocial characteristics of Hong Kong male and female adolescents. Youth & Society 2019;51(1):3-29. ↵

- Chan HC, Wong DS. Traditional school bullying and cyberbullying perpetration: Examining the psychosocial characteristics of Hong Kong male and female adolescents. Youth & Society 2019;51(1):3-29. ↵

- Gaffney H, Farrington DP, Espelage DL, Ttofi MM. Are cyberbullying intervention and prevention programs effective? A systematic and meta-analytical review. Aggression and violent behavior 2019;45:134-153. ↵

- Doty JL, Giron K, Mehari KR, Sharma D, Smith SJ, Su Y, et al. Interventions to Prevent Cyberbullying Perpetration and Victimization: A Systematic Review. Prevention Science in press. ↵

- Pearce N, Cross D, Monks H, Waters S, Falconer S. Current evidence of best practice in whole-school bullying intervention and its potential to inform cyberbullying interventions. Journal of Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools 2011;21(1):1-21. ↵

- Doty JL, Giron K, Mehari KR, Sharma D, Smith SJ, Su Y, et al. Interventions to Prevent Cyberbullying Perpetration and Victimization: A Systematic Review. Prevention Science in press. ↵

- Gonzales J, Mehari KR. Attitudes about Cyber Intimate Partner Violence: Scale Development and Preliminary Psychometrics. 2021. ↵

- Sharma D, Mehari KR, Doty JL. Stakeholder Focus Groups on Cyberbullying in India. 2021. ↵

- Ang RP, Goh DH. Cyberbullying among adolescents: The role of affective and cognitive empathy, and gender. Child Psychiatry & Human Development 2010;41(4):387-397. ↵

- Willard NE. The authority and responsibility of school officials in responding to cyberbullying. Journal of Adolescent Health 2007;41(6):S64-S65. ↵

- Smith PK, Mahdavi J, Carvalho M, Fisher S, Russell S, Tippett N. Cyberbullying: Its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry 2008;49(4):376-385. ↵

- Bauman S. Cyberbullying in a rural intermediate school: An exploratory study. The Journal of Early Adolescence 2010;30(6):803-833. ↵

- Agatston PW, Kowalski R, Limber S. Students’ perspectives on cyber bullying. Journal of Adolescent Health 2007;41(6):S59-S60. ↵

- Slonje R, Smith PK. Cyberbullying: Another main type of bullying? Scand J Psychol 2008;49(2):147-154. ↵

- Cassidy W, Brown K, Jackson M. “Making Kind Cool”: Parents’ Suggestions for Preventing Cyber Bullying and Fostering Cyber Kindness. Journal of Educational Computing Research 2012;46(4):415-436. ↵

- Hodges EV, Boivin M, Vitaro F, Bukowski WM. The power of friendship: protection against an escalating cycle of peer victimization. Dev Psychol 1999;35(1):94. ↵

- Hertz MF, David-Ferdon C. Electronic media and youth violence: A CDC issue brief for educators and caregivers. : Centers for Disease Control Atlanta, GA; 2008. ↵

- Horner RH, Sugai G. School-wide PBIS: An example of applied behavior analysis implemented at a scale of social importance. Behavior analysis in practice 2015;8(1):80-85. ↵

- Willard NE. The authority and responsibility of school officials in responding to cyberbullying. Journal of Adolescent Health 2007;41(6):S64-S65. ↵

- Willard NE. The authority and responsibility of school officials in responding to cyberbullying. Journal of Adolescent Health 2007;41(6):S64-S65. ↵

- Shariff S. Confronting Cyber-Bullying: What Schools Need to Know to Control Misconduct and Avoid Legal Consequences. : ERIC; 2009. ↵

- Bauman S. Cyberbullying in a rural intermediate school: An exploratory study. The Journal of Early Adolescence 2010;30(6):803-833. ↵

- Agatston PW, Kowalski R, Limber S. Students’ perspectives on cyber bullying. Journal of Adolescent Health 2007;41(6):S59-S60. ↵