Chapter 5: Going Beyond Cyberbullying: Adolescent Online Safety and Digital Risks

Anthony T. Pinter; Arup Kumar Ghosh; and Pamela J. Wisniewski

ABSTRACT

In this chapter, we cover the broader research area of digital risks and online safety. We discuss three primary types of risks that adolescents frequently navigate in digitally mediated environments that extend beyond cyberbullying – 1) Sexual Solicitations and Risky Sexual Behavior, 2) Exposure to Explicit Content, and 3) Information Breaches and Privacy Violations. We discuss the competing perspectives around how to approach adolescent online risks. We also discuss how those perspectives tend to lead to abstinence-only versus resilience-based frameworks of addressing adolescent online safety. We close by highlighting the Western-centric nature of existing work and the need for more work addressing Eastern cultures. This includes Indian contexts to better understand how the existing work applies to and may differ to Indian-based researchers, educators, and policymakers.

Adolescent internet use has substantially grown across the world, particularly in developing nations. In Western contexts, approximately 95% of teenagers in the United States (U.S.) have access to a smartphone. 45% of them are online ‘almost constantly.’[1] Adolescent internet access and use in Eastern contexts, and particularly in India, has also grown significantly in recent years. A 2020 CRY study[2] surveyed adolescents in Delhi-NCR and found that 93% of Indian adolescents had internet access at home, and 54% owned mobile devices. Half of the survey respondents had at least two internet-enabled devices. Social media usage is also prevalent among teens in the U.S. with some differences related to gender and/or ethnicity.

With the increased accessibility of the internet during the mid-to-late 2000s, researchers turned their attention to adolescents. They focused on understanding how adolescents were using the internet and the challenges that youth encounter online. While online harassment and cyberbullying have been at the forefront of adolescent online safety research, this chapter highlights and synthesizes research related to the three additional online risk types relevant to teens: 1) Sexual Solicitations and Risky Sexual Behavior, 2) Exposure to Explicit Content, and 3) Information Breaches and Privacy Violations. Accordingly, we offer an overview of work centered on these risks to better contextualize cyberbullying as a subject of study. The study should be such that it is important but does not stand alone within the field of adolescent online safety. We introduce four risk types and summarize relevant research on each topic.

Further, we highlight a trend towards a heavy prevalence of work focused on “abstinence-based” approaches of increasing parental control. We also discuss relational processes focused on the parent-teen relationship, to shield youth from experiencing online risks,[3] rather than more individualistic or resilience-based approaches. Resilience-based approaches emphasize youth self-regulation as an alternative strength-based approach that helps youth overcome the negative effects of online risk exposure and benefit from the opportunities the internet has to offer.[4],[5],[6],[7],[8],[9],[10],[11],[12] We compare and contrast these two different perspectives within the adolescent online safety literature. We also acknowledge that the individualistic and autonomy-based approach to adolescent online safety promoted in Westernized contexts may or may not be generalizable to Eastern cultures. In Eastern culture collectivism and authoritarian parenting styles are more common.[13] We close this chapter with a discussion of work related to digital safety in Western vs. Eastern contexts to highlight the overabundance of research being conducted in Western contexts and the need for more work that focuses on the lived experiences of Indian youth.

ADOLESCENT ONLINE SAFETY: RISKS AND PROTECTIVE FACTORS

A common theme in online safety literature has been to identify the factors that put adolescents at risk versus the protective factors that either mitigate exposure to online risks or the negative outcome associated with risk exposure. Therefore, we provide a brief definition of each digital risk posed to youth. We then discuss the risk and protective factors that have been identified in the literature for each risk type. Protective factors may occur at varying levels of the ecological model, ranging from the individual, relational, interactional, community, or societal levels.

ONLINE SEXUAL SOLICITATIONS AND SEXUAL RISK BEHAVIOR

Online sexual predation of youth is defined as unwanted sexual solicitations from others (regardless of age) or any solicitations of a sexual nature made by adults through internet-enabled technologies.[14] Meanwhile, risky online sexual behaviors involve youth engaging in technology-mediated sexual exchanges, such as sex talk, sharing sexual imagery, and meeting online contacts for offline sexual encounters.[15],[16] Over half of youth in the U.S. (ages 10 to 17) have received at least one online sexual solicitation in the past year.[17] Meanwhile, 15% of teens reported receiving pornographic images via text message (“sexting”). 4% admitted sending such messages to others via their mobile devices.[18] Many news outlets have reported the increasing trend of sexting among Indian youth although no formal research studies have been conducted.[19] In one survey study, researchers found more than half of young adult respondents sent sexually explicit text messages to their friends.[20] Researchers have identified several factors that contribute to an adolescent’s likelihood of experiencing sexual solicitation or related risk exposures. The two largest risk factors were – (1) gender (with girls being more likely to experience online sexual solicitations)[21],[22],[23],[24],[25] and (2) frequently using the internet,[26],[27],[28],[29],[30] especially to access pornographic material.[31] Meanwhile, the line between offline and online sexual predation and abuse is blurred as many sex offenders who know their victims in person, also communicate with them online.[32]

Teens between the ages of 12 and 15, racial minorities, and girls are the most “at-risk” of being solicited and engaging in risky sexual behaviors online.[33],[34],[35],[36] This also includes people who have histories of neglect, abuse, family instability, lack of parental involvement, emotional, behavioral, or cognitive problems. This risk exposure may lead to an increased likelihood of offline sexual encounters.[37],[38] These can result in physical harm, teen pregnancy, sexual transmitted diseases, and in extreme cases, sexual abuse[39],[40],[41] or sex trafficking.[42],[43] Both offline and online sexual abuse can negatively impact youths’ academic, cognitive, emotional, and psychological development. It has been associated with increased cyber-victimization, drug abuse, suicide, and death.[44],[45],[46]

Whittle et al.’s[47] comprehensive review of the online sexual grooming literature synthesized risk factors (e.g., gender, age, poor family relationships, etc.) that make some youth more vulnerable to sexual predation risks than others. This work identified parental involvement as the primary protective factor against online sexual risks. This focus on parental mediation as a means of protecting teens from online risks is consistent with the broader literature on adolescent online safety.[48],[49],[50],[51] In other words, researchers have found that teens who are most protected from online sexual solicitations had parents who actively mediated their internet use.[52],[53] Teens were also protected through caution, including the fear of being punished or getting in trouble was often enough to significantly reduce the likelihood of being exposed to online sexual risks.[54]

To date, most interventions for preventing online sexual predation of at-risk youth have targeted understanding, identifying, and comprehending online sex predators[55],[56],[57],[58],[59], rather than preventing youth from becoming victims. These prevention initiatives often occur at the societal or community level involving child protection and law enforcement organizations. As such, research in this domain focuses on victimized youth or individuals who have already suffered the consequences of sexual abuse.[60],[61],[62] However, Razi et al.[63] recently conducted an analysis of 4,180 posts made by teens (ages 12-17) on an online peer support mental health forum to understand what and how adolescents talk about their online sexual interactions. The researchers found that youth used the platform to seek support (83%), connect with others (15%), and give advice (5%) about sexting, their sexual orientation, sexual abuse, and explicit content. Thus, peer support, even from strangers, may also be an important protective factor. At the relational level of the ecological framework, this support can help teens navigate how to handle unwanted sexual solicitations and risky situations online.

EXPOSURE TO INAPPROPRIATE AND EXPLICIT CONTENT

The term “explicit content” covers a wide range of inappropriate online materials. This includes but is not limited to pornographic, violent, gruesome, or hateful content, as well as content that promotes harmful behaviors such as self-harm or eating disorders.[64],[65],[66],[67] Work focused on explicit content exposure has identified two types of exposure: willful and accidental exposures. This means adolescents may intentionally seek out inappropriate content online, but some may be accidentally exposed.[68] According to the Youth Internet Safety Survey,[69] about a quarter of youth in the U.S. had been exposed to unwanted pornography. A multinational study of youth in the U.S., Finland, and Germany found that 17% of the youth had been exposed to online content involving eating disorders, 11% to self-injury content, and 8% to suicide.[70] A 2020 IGPP survey[71] found nearly 50% of the Indian youth respondents accepted to have watched online pornographic content. 40% recognized to know people who have watched pornographic content on the internet. Yet, a U.S. diary study of adolescents (ages 13-17)[72] found that teens reported being exposed to explicit content four times more often than they experienced cyberbullying, sexual solicitations, or information breaches online. The majority of the time exposure was accidental.

Even though exposure may be accidental, researchers have found a negative correlation between adolescents’ repeated viewing of explicit content and several negative outcomes. These negative outcomes include a link between pornography and committing dating violence[73],[74], acts of digital self-harm with increased non-suicidal self-harm and suicidal ideation,[75] and violent content embedded within video games linked to aggressive behavior.[76] However, some media scholars[77],[78],[79] argue that the negative effects of explicit content exposure on youth are largely over-claimed or biased, and therefore, should not be generalized.

The risk factors that make some youth more susceptible to explicit content exposure vary based on the type of content. For instance, male teens are more likely to seek out online pornography than females. The majority of teens who seek out sexual images online are 14 years of age or older.[80] This research suggests that concerns about younger children’s exposure to online pornography may be overstated. It also suggests that adolescence is a developmentally appropriate time to become curious about sex. Therefore, some researchers have encouraged making a distinction between problematic (e.g., compulsive or addictive use) and non-problematic pornography use. This distinction is especially needed among vulnerable youth populations, such as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) adolescents. Such communities may use such materials to learn about sexuality and develop their sexual identities.[81] Other studies found that female youth are more likely to see online content regarding eating disorders, while males are more likely to view violent, pro-self-harm, and pro-suicide content.[82]

While exposure to explicit content is quite prevalent among adolescent youth, the protective factors against such exposure are few. For instance, reducing the frequency of internet use is detrimental due to hindering the positive opportunities for online engagement.[83],[84] Some researchers have found that filtering and blocking software can be effective.[85] For instance, Ybarra, et al. found that pop-up or spam blockers reduced the chances of teens being exposed to unwanted sexual material by 59%. They also found that filtering and monitoring software further reduced the chance of this risk exposure occurring by 65%.[86] Yet, others have found that such parental control software may be more appropriate for younger children[87] as adolescents resent restrictive parenting practices that hinder their desire for autonomy.[88] Parental control software has been shown to be ineffective, and even damaging, to the trust relationship between parents and teens.[89],[90],[91],[92] Additionally, there is little evidence that these technologies actually keep teens safe online or teach them to effectively manage online risks.[93] Active mediation and instructive co-viewing is situation where a parent is aware of the online activities of their children and openly discusses inappropriate content in a non-judgmental way. It may be the best approach to support adolescents when exposed to explicit content online.[94] This protective strategy would occur at the relational and individual levels of the socio-ecological framework with parents directly supporting their children’s online experiences.

INFORMATION BREACHES AND PRIVACY VIOLATIONS

Information breaches or privacy violations involve the inappropriate sharing of sensitive information (e.g., account credentials or location information) online by the youth themselves or by others without the teen’s permission.[95],[96],[97],[98] The online world creates a wide variety of options for collecting, processing, and distributing users’ personal information. Therefore, information privacy has been the target of considerable controversy[99] and research.[100] Yet, beyond the Child Online Privacy Protection Act, no existing law in the U.S. protects the online information privacy of teenagers. making them more vulnerable to information breaches and privacy violations.[101] The rapid emergence of social networking sites, such as Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat are rife with opportunities for teens to reveal personal information.[102],[103] As a result, teens share more personal information and still report relatively low levels of privacy concern.[104] In contrast, 81% of their parents are “somewhat” to “very” concerned about their teens’ online privacy.[105]

In examining factors that lead to information breaches and privacy violations, several predictive factors have been identified: frequency of internet use[106],[107], internet skill[108],[109],[110], and privacy concern.[111],[112] In other words, teens who use the internet more often, do more things online. But they lack the skills to protect themselves and are less concerned about their online privacy, encounter more information breaches. Other factors have been noted to either increase or decrease the likelihood of exposure to this risk type. From a socio-economic standpoint, adolescents who come from more affluent backgrounds are more likely to experience higher rates of privacy violations.[113] Perhaps connected with the frequency of use, adolescents from wealthier backgrounds may have more readily available Internet access in their homes. Perhaps they have internet access even in spaces that are more private from parents (i.e., spaces that are harder for parents to actively monitor, like adolescents’ bedrooms). However, other aspects of adolescents’ lives offer forms of protection from this type of risk exposure. For example, adolescents who are in a romantic relationship are less likely to experience information breaches.[114] Given that information privacy often co-occurs with or results from exposure to other risk types – particularly sexual solicitations. Being in a relationship may preclude teens from seeking out the types of content or connections online that result in information and privacy breaches.

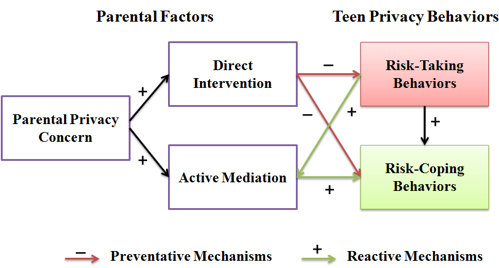

Meanwhile, there have been mixed findings regarding how parents can mitigate these online risks. One study found that parental restrictions against giving out personal information online are associated with a higher likelihood that teens disclose such personal information.[115] Another study[116] confirmed that parental mediation was not significantly related to tweens’ (ages 9 – 12) willingness to disclose personal information online. The larger the discrepancy between parental and tween perceptions of online restrictive mediation, the more willing tweens were to make online disclosures. A study by Wisniewski et al.[117] found that direct intervention by parents was associated with teens making fewer online disclosures. However, active mediation through talking with teens, searching teens’ information, and responding directly to teens’ online posts was more effective in helping teach teens how to take appropriate risk-coping measures. The relationships between parenting practices and teen social media privacy behaviors are illustrated in Figure 7.

This research suggests that preventative and restrictive parenting practices may reduce teens’ overall information disclosures. But this can also limit their opportunities for engaging with others online in beneficial and meaningful ways. Therefore, taking a dual approach of some direct intervention combined with active mediation may be the best approach to help teens navigate information privacy risks. At the societal level, legislation, such as the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) in the United States, and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the European Union provide additional privacy protection for young internet users. However, most protective factors identified in the literature remain at the relational (i.e., parent-teen) and individual levels of the ecological framework.

Now that we have summarized some of the risk and protective factors that are associated with these three types of online risks, we now discuss two different approaches to promoting adolescent online safety.

ABSTINENCE-ONLY VERSUS RESILIENCE-BASED APPROACHES

Research has identified the risk and protective factors associated with the three risk types previously discussed. But less attention has been given to designing effective interventions to prevent exposure or mitigate the consequences of exposure,[118] or helping teens to be resilient in spite of encountering online risks.[119] Pinter et al.[120] conducted a comprehensive review of the adolescent online safety literature and concluded that research has traditionally advanced an “abstinence-based” framework of adolescent online safety and risk exposure. 69% of the studies reviewed focused on minimizing or eradicating online risk exposure, rather than teaching youth to effectively cope with these risks once they occur.[121] Researchers from EU Kids Online were among the first to argue that adolescent exposure to online risks does not necessarily equate to harm.[122],[123] They found that youth who reported having more psychological problems and/or lower self-efficacy tended to become more bothered when experiencing these online risks while other teens remained unbothered.[124]

Wisniewski et al.[125] were one of the first to apply the adolescent resilience framework, at the individual-level, to teen risky behaviors that are linked to internet use. Resilience-based approaches differ from risk-averse approaches by “focusing on the assets and resources that enable adolescents to overcome the negative effects of risk exposure”,[126] rather than trying to limit exposure to risk. Another way of understanding the contrast is that the resilience perspective leads to a focus on teen strengths rather than their deficits. Wisniewski et al.’s[127] work showed evidence that resilience is a key factor in protecting teens from experiencing online risks, even when teens exhibit high levels of internet addiction. Resilience also neutralizes the negative psychological effects associated with internet addiction and online risk exposure. In Wisniewski et al.’s subsequent work,[128] they found that teens can potentially benefit from experiencing lower-risk online situations. This allows them to develop crucial interpersonal skills, such as boundary setting, conflict resolution, and empathy. Developmental psychology reminds us that some level of risk-taking and experiential learning is necessary for normal aspects of adolescent developmental growth.[129] Thus, we need to strike a healthy balance between allowing teens to learn how to safely engage online through experiencing some risk and protecting them from high-risk situations.

We emphasize the importance of designing solutions that foster teen resilience and strength building at the individual level, as opposed to solutions targeted toward parents (i.e., at the relational level) that often focus on restriction and risk prevention. Similarly, Hartikainen et al.[130] found that building parent-teen trust led to better communication. It in turn created more opportunities for positive outcomes when compared to more restrictive, control-based approaches.[131] boyd agreed, arguing that abstinence or control-based approaches prevent adolescents from learning self-protection or coping skills.[132] For instance, teen resilience can be promoted directly through web-based educational or counseling programs that help build resilience.[133] We can also promote this through interface designs that empower teens to take protective measures upon encountering online risks. For example, Facebook provides a “Family Safety Center” that offers tips for teens to develop better online safety practices.[134] Several researchers have called for new online safety solutions that move away from parental control toward promoting positive parent-teen relationships and teen self-regulation of their online behaviors (e.g., [135],[136],[137],[138]). Yet, few, if any, technological interventions for adolescent online safety have been developed to help teens self-regulate and manage online risks in a meaningful way.[139]

In the next section, we present a framework of Teen Online Safety Strategies (TOSS) that illustrates the tensions between promoting online safety from the perspectives of parental control versus teen self-regulation.

PARENTAL CONTROL VERSUS TEEN SELF-REGULATION STRATEGIES

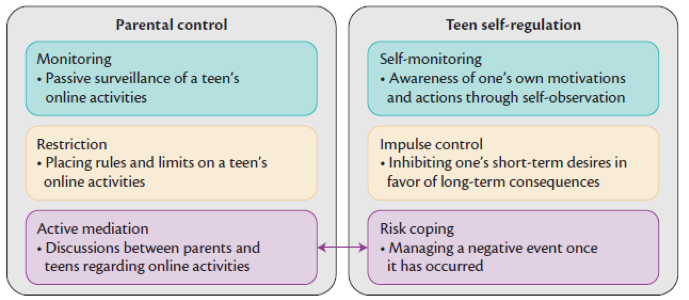

The Teen Online Safety Strategies (TOSS) framework,[140] shown in Figure 8, is built upon the rationale that adolescent online safety can be framed as an outcome of effective parenting. It assumes that parents directly influence or control teens’ exposure to online risks.[141],[142],[143],[144] This explains tensions between parental control and teen self-regulation when it comes to teens’ online behaviors, their desire for privacy, and online safety.[145],[146],[147],[148] In the TOSS framework, parental control strategies include monitoring (passive surveillance of a teen’s online activities), restriction (placing rules and limits on a teen’s online activities), and active mediation (discussion between parents and teens regarding online activities). These strategies were based primarily on Valkenburg et al.’s[149] foundational work, which created scales assessing three styles of parental television mediation. They have since widely been adapted for use in the context of online parental mediation.[150],[151],[152],[153] The framework also positions teen self-regulation strategies that work as resiliency factors and protect teens from online risks. Such resilience-based factors align with the individual-level processes of the ecological model of cyberbullying and online risks. Specifically, three of its key components – self-awareness (awareness of one’s own motivations and actions through self-observation), impulse control (inhibiting one’s short-term desires in favor of long-term consequences), and risk-coping (managing a negative event once it has occurred) – acknowledge the importance of and encourage teen self-regulation.

Wisniewski, Ghosh, and their co-authors[154] applied the TOSS framework to better understand the commercially available technical offerings that support adolescent online safety, and what teens thought about these applications. They found that an overwhelming majority of mobile app features (89%) supported parental control through monitoring (44%) and restriction (43%). Not much support was seen in these apps to facilitate parents’ active mediation or support any form of teen self-regulation. Further, many of the apps were extremely privacy invasive. They provided parents granular access to monitor and restrict teens’ intimate online interactions with others. This includes their browsing history, the apps installed on their phones, and the text messages teens sent and received. Teen risk coping was minimally supported by an “SOS feature” that teens could use to get help from an adult.

In a follow-up study, Ghosh, Wisniewski, and their co-authors[155] analyzed 736 reviews of these parental control apps that were publicly posted by teens and younger children on Google Play. They found that the majority (79%) of children overwhelmingly disliked the apps, while a small minority (21%) of reviews saw benefits to the apps. Children rated the apps significantly lower than parents. Teens, and even younger children, strongly disliked these apps because they felt that they were overly restrictive and invasive of their personal privacy. They negatively impacted their relationships with their parents. A takeaway from this research was that, as researchers and designers, we should consider listening to what teens have to say about the technologies designed to keep them safe online. We should conceptualize new solutions that engage parents and respect the challenges teens face growing up in a networked world.

Next, we discuss whether the resilience-based approaches aimed at promoting teen self-regulation are relevant and applicable to Indian youth and other Eastern contexts.

CROSS-CULTURAL COMPARISONS OF ADOLESCENT ONLINE SAFETY AND RISKS BETWEEN THE U.S. AND INDIA

According to Pinter et al.’s review of the adolescent online safety literature,[156] the majority (44%) of the studies originated from the U.S.[157],[158],[159],[160] The second and third most prevalent countries of origin were the Netherlands and Great Britain., representing 9% and 8% of the articles, respectively. Canada had the fourth-highest representation in the sample with 5% of the articles, followed by Spain (3%) and Korea (3%). Only 5% of the studies in their sample studied adolescent online safety and risks multi-nationally. Of these, one compared adolescents in Canada and China,[161] another U.S. and Finland,[162] and the rest studied adolescents from multiple European countries.[163],[164],[165] A number of the multi-national studies across Europe were in conjunction with the initiative launched by EU Kids Online, a multinational research network.[166],[167],[168] Meanwhile, there is a dearth of research related to adolescent online safety and risks specifically from India.

With differing cultural norms, the Western-centric research on adolescent online safety may not be as applicable in other contexts, such as sub-Asian locales like India. Different cultures are likely to approach risk exposure, prevention, and coping differently, and a disparate focus on one nation limits research’s ability to understand adolescents’ risk experiences. It is not the most effective way for parents to intervene. For instance, parenting styles vary drastically across different cultures. Indian mothers in America are more likely to use authoritative parenting styles (an approach to child-rearing that combines warmth, sensitivity, and the setting of limits). Parents residing in India are more inclined to use authoritarian parenting styles (characterized by high demands and low responsiveness).[169] While authoritative parenting styles have been shown to have positive youth outcomes within Indian families,[170] more authoritarian parenting styles may be more effective within different cultures and ethnicities (e.g., [171],[172]). Therefore, families from Eastern cultures need to be better represented in research. For instance, Asian adolescents have recently come into the public eye as particularly susceptible to internet addiction.[173],[174] Further, countries that are more collective than individualistic in culture may rely more heavily on relational, interactional, community, and societal level approaches when taking an ecological approach to risk prevention. They may focus less on individualistic approaches, such as fostering teen resilience and self-regulation. To date, this trend has been supported in the literature.

Recently, research on adolescent technology use has emerged from Eastern contexts. Garg and Sengupta[175] conducted a comparative study between U.S. and Asian Indian youth. They found both differences and similarities in parents’ attitudes about digital technology use. For example, Asian Indian families took more authoritarian approaches than White families when it came to deciding whether children below the age of 13 could have their own mobile phones. Parents across demographics allowed children above the age of 13 to have their own devices or permitted them to use the common family device or their parents’ devices. Both White and Indian children between ages 14-17 had at least one social media account. A few Indian parents created online profiles of their young children so that they could co-use and help maintain the bonds between grandparents (staying in India) and grandchildren. Working parents, irrespective of their race, did have concerns about the content children accessed online. White middle-class parents tried to enforce restrictions on children’s smartphone usage based on context and in a way that supports child self-regulation and autonomy. Their Indian counterparts were more rules dependent. As there are both differences and similarities in U.S. and Indian parents’ attitudes about digital technology use, it may be possible to apply some of the western approaches to Indian contexts. But it is not possible to be so sure without conducting more research work that focuses on the lived experiences of Indian youth. Additionally, more research needs to be done that extends beyond the parent-teen relationship to study interactional, community, and societal level factors that could promote the online safety of Indian youth more collectively.

With the growing concern in other contexts such as Indian adolescents, incorporating more resilience-based approaches may be beneficial to researchers, practitioners, and policymakers in protecting adolescents. But this should be done without impeding healthy growth and self-regulation behaviors.

In the next chapter we discuss the research and policy implications in India. Chapter Six addresses the more distal societal level factors identified by the model. We summarize how the current knowledge can be applied in India across multiple stakeholder groups, including public policy, law enforcement, school administration, health care providers, community-based organizations, tech industry, and research institutes. Also, we highlight the key gaps in knowledge to guide future research.

CONCLUSION

In this chapter, we introduce the broader field of adolescent online safety research beyond that of cyberbullying. We characterize four types of risks that online safety researchers have identified. We further discuss the prevalent framing of adolescent online safety as resulting from abstinence or preventative approaches instead of approaches encouraging resilience. We contrast that approach with more nascent framings of safety as being resilient in nature – encouraging teens to evaluate and make decisions for themselves and then designing and implementing approaches meant to encourage coping. Regardless of the approach taken, cultural norms and expectations undoubtedly play a role in how these framings are researched and put into action. However, the state of research in Indian and other Eastern contexts is severely lacking in comparison to Western contexts. The disparity in existing available work between Eastern and Western contexts provides ample opportunities for researchers to address. It is an issue that is timely as Indian adolescents access the Internet as much as (if not more than) their American counterparts. We argue that while cyberbullying is prevalent, there are other risks to be considered when mobilizing to address the lack of work on digital safety in Indian contexts. So more holistic examinations of adolescents’ experiences online in India will benefit not only Indian contexts but the state of the research as a whole.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Digital risk and online safety encompass more than just cyberbullying and online harassment. Each risk type has unique factors that contribute to an adolescent’s likelihood of experiencing that risk. However, common factors across all four risk types include age, gender, level of Internet efficacy, and frequency of Internet use.

- There are two principal approaches to understanding adolescent risk and safety online – abstinence-based and resilience-based approaches. Abstinence-based approaches dominate existing research, focusing on preventing risk exposure entirely via control and regulation.

- Resilience-based approaches focus on encouraging coping and growth in the aftermath of risk exposure and encouraging adolescent self-regulation.

- Much of the existing work focuses on Western contexts, particularly the United States. With the growing concern in other contexts such as Indian adolescents, incorporating more resilience-based approaches may be beneficial to researchers, practitioners, and policymakers in protecting adolescents while not impeding healthy growth and self-regulation behaviors.

- Anderson M, Jiang J. Teens, Social Media & Technology 2018 [Internet]. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. 2018 [cited 2018 Jul 15]. Available from: http://www.pewinternet.org/2018/05/31/teens-social-media-technology-2018/ ↵

- Child Rights and You (CRY). Online Safety and Internet Addiction (A Study Conducted Amongst Adolescents in Delhi-NCR). New Delhi; 2020. ↵

- Shin W, Ismail N. Exploring the Role of Parents and Peers in Young Adolescents’ Risk Taking on Social Networking Sites. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2014 Sep;17(9):578–83. ↵

- Wisniewski P, Ghosh AK, Rosson MB, Xu H, Carroll JM. Parental Control vs. Teen Self-Regulation: Is there a middle ground for mobile online safety? Proceedings of the 20th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing. 2017; ↵

- Ghosh AK, Badillo-Urquiola K, Guha S, LaViola JJ, Wisniewski PJ. Safety vs. Surveillance: What Children Have to Say about Mobile Apps for Parental Control. In the Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI). 2018; ↵

- Ghosh AK, Badillo-Urquiola K, Rosson MB, Xu H, Carroll J, Wisniewski P. A Matter of Control or Safety? Examining Parental Use of Technical Monitoring Apps on Teens’ Mobile Devices. In the Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI). 2018; ↵

- Ghosh AK, Badillo-Urquiola K, Wisniewski P. Examining the Effects of Parenting Styles on Offline and Online Adolescent Peer Problems. In: Proceedings of the 2018 ACM Conference on Supporting Groupwork [Internet]. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2018 [cited 2020 Nov 7]. p. 150–3. (GROUP ’18). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1145/3148330.3154519 ↵

- Ghosh AK, Badillo-Urquiola KA, Xu H, Rosson MB, Carroll JM, Wisniewski P. Examining Parents’ Technical Mediation of Teens’ Mobile Devices. In: Companion of the 2017 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing [Internet]. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2017. p. 179–82. (CSCW ’17 Companion). Available from: http://doi.acm.org/10.1145/3022198.3026306 ↵

- Ghosh AK. Taking a More Balanced Approach to Adolescent Mobile Safety. In: Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Supporting Group Work [Internet]. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2016. p. 495–8. (GROUP ’16). Available from: http://doi.acm.org/10.1145/2957276.2997025 ↵

- Ghosh AK. Using a Value Sensitive Design Approach to Promote Adolescent Online Safety on Mobile Platforms. In: 2016 International Conference on Collaboration Technologies and Systems (CTS). 2016. p. 593–6. ↵

- Ghosh AK, Wisniewski P. Understanding User Reviews of Adolescent Mobile Safety Apps: A Thematic Analysis. In: Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Supporting Group Work [Internet]. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2016 [cited 2017 Apr 26]. p. 417–20. (GROUP ’16). Available from: http://doi.acm.org/10.1145/2957276.2996283 ↵

- Ghosh AK, Wisniewski PJ, Hughes CE. Circle of Trust: A New Approach to Mobile Online Safety for Families. In the Proceedings of the ACM CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI) [Internet]. 2020; Available from: https://dl.acm.org/doi/fullHtml/10.1145/3313831.3376747 ↵

- Jambunathan S, Counselman K. Parenting Attitudes of Asian Indian Mothers Living in the United States and in India. Early Child Development and Care. 2002 Dec 1;172(6):657–62. ↵

- Jones LM, Mitchell KJ, Finkelhor D. Trends in Youth Internet Victimization: Findings From Three Youth Internet Safety Surveys 2000–2010. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012 Feb 1;50(2):179–86. ↵

- Jonsson LS, Priebe G, Bladh M, Svedin CG. Voluntary sexual exposure online among Swedish youth – social background, Internet behavior and psychosocial health. Computers in Human Behavior. 2014 Jan;30:181–90. ↵

- Noll JG, Shenk CE, Barnes JE, Haralson KJ. Association of Maltreatment With High-Risk Internet Behaviors and Offline Encounters. Pediatrics. 2013 Feb 1;131(2):e510–7. ↵

- Mitchell K, Jones L, Finkelhor D, Wolak J. Trends in Unwanted Online Experiences and Sexting : Final Report. Crimes Against Children Research Center [Internet]. 2014 Feb 1; Available from: http://scholars.unh.edu/ccrc/49 ↵

- Amanda Lenhart. Teens and Sexting [Internet]. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. 2009 [cited 2016 Jul 13]. Available from: http://www.pewinternet.org/2009/12/15/teens-and-sexting/ ↵

- Sexting culture fast catching up with Indian teens – Times of India [Internet]. The Times of India. [cited 2021 Feb 25]. Available from: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/home/science/sexting-culture-fast-catching-up-with-indian-teens/articleshow/14684015.cms ↵

- Indian women outdo men in sexting and filming sexual video content: Survey | India News – Times of India [Internet]. The Times of India. [cited 2021 Feb 25]. Available from: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/indian-women-outdo-men-in-sexting-and-filming-sexual-video-content-survey/articleshow/30172628.cms ↵

- Livingstone S, Helsper EJ. Balancing opportunities and risks in teenagers’ use of the internet: the role of online skills and internet self-efficacy. New Media & Society. 2010 Mar 1;12(2):309–29. ↵

- Livingstone S, Kirwil L, Ponte C, Staksrud E. In their own words: What bothers children online? European Journal of Communication. 2014;29(3):271–88. ↵

- Helweg-Larsen K, Schütt N, Larsen HB. Predictors and protective factors for adolescent Internet victimization: results from a 2008 nationwide Danish youth survey: Adolescent internet victimization. Acta Paediatrica. 2012 May;101(5):533–9. ↵

- Pedersen S. UK young adults’ safety awareness online – is it a ‘girl thing’? Journal of Youth Studies. 2013 May;16(3):404–19. ↵

- Pujazon-Zazik MA, Manasse SM, Orrell-Valente JK. Adolescents’ Self-presentation on a Teen Dating Web Site: A Risk-Content Analysis. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012 May;50(5):517–20. ↵

- Ybarra ML, Mitchell KJ. How Risky Are Social Networking Sites? A Comparison of Places Online Where Youth Sexual Solicitation and Harassment Occurs. PEDIATRICS. 2008 Jan 28;121(2):e350–7. ↵

- Rice E, Winetrobe H, Holloway IW, Montoya J, Plant A, Kordic T. Cell Phone Internet Access, Online Sexual Solicitation, Partner Seeking, and Sexual Risk Behavior Among Adolescents. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2015 Apr;44(3):755–63. ↵

- Blau I. Comparing online opportunities and risks among Israeli children and youth Hebrew and Arabic speakers. New Review of Hypermedia and Multimedia. 2014 Oct 2;20(4):281–99. ↵

- Doornwaard SM, ter Bogt TFM, Reitz E, van den Eijnden RJJM. Sex-Related Online Behaviors, Perceived Peer Norms and Adolescents’ Experience with Sexual Behavior: Testing an Integrative Model. Zeeb H, editor. PLOS ONE. 2015 Jun 18;10(6):e0127787. ↵

- Ybarra ML, Mitchell KJ, Korchmaros JD. National Trends in Exposure to and Experiences of Violence on the Internet Among Children. PEDIATRICS. 2011 Dec 1;128(6):e1376–86. ↵

- Doornwaard SM, Bickham DS, Rich M, Vanwesenbeeck I, van den Eijnden RJJM, ter Bogt TFM. Sex-Related Online Behaviors and Adolescents’ Body and Sexual Self-Perceptions. PEDIATRICS. 2014 Dec 1;134(6):1103–10. ↵

- Wolak J, Finkelhor D, Mitchell KJ, Ybarra ML. Online “predators” and Their Victims: Myths, Realities, and Implications for Prevention and Treatment. Psychology of Violence. 2010 Aug 1;1(S):13–35. ↵

- Jonsson LS, Priebe G, Bladh M, Svedin CG. Voluntary sexual exposure online among Swedish youth – social background, Internet behavior and psychosocial health. Computers in Human Behavior. 2014 Jan;30:181–90. ↵

- Noll JG, Shenk CE, Barnes JE, Haralson KJ. Association of Maltreatment With High-Risk Internet Behaviors and Offline Encounters. Pediatrics. 2013 Feb 1;131(2):e510–7. ↵

- Jonsson LS, Svedin CG, Hydén M. “Without the Internet, I never would have sold sex”: Young women selling sex online. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace [Internet]. 2014 Mar 1 [cited 2017 May 24];8(1). Available from: https://journals.muni.cz/cyberpsychology/article/view/4297 ↵

- Whittle H, Hamilton-Giachritsis C, Beech A, Collings G. A review of young people’s vulnerabilities to online grooming. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2013 Jan;18(1):135–46. ↵

- Noll JG, Shenk CE, Barnes JE, Haralson KJ. Association of Maltreatment With High-Risk Internet Behaviors and Offline Encounters. Pediatrics. 2013 Feb 1;131(2):e510–7. ↵

- Schulz A, Bergen E, Schuhmann P, Hoyer J, Santtila P. Online Sexual Solicitation of Minors: How Often and between Whom Does It Occur? Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2016 Mar 1;53(2):165–88. ↵

- Whittle H, Hamilton-Giachritsis C, Beech A, Collings G. A review of young people’s vulnerabilities to online grooming. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2013 Jan;18(1):135–46. ↵

- Dombrowski SC, LeMasney JW, Ahia CE, Dickson SA. Protecting Children From Online Sexual Predators: Technological, Psychoeducational, and Legal Considerations. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2004 Feb;35(1):65–73. ↵

- Slavtcheva-Petkova V, Nash VJ, Bulger M. Evidence on the extent of harms experienced by children as a result of online risks: implications for policy and research. Information, Communication & Society. 2015 Jan 2;18(1):48–62. ↵

- Ibanez M. Virtual Red Light Districts: Detecting Covert Networks and Sex Trafficking Circuits in the U.S. ProQuest LLC; 2015. ↵

- Tidball S, Zheng M, Creswell J. Buying Sex On-Line from Girls: NGO Representatives, Law Enforcement Officials, and Public Officials Speak out About Human Trafficking-A Qualitative Analysis. Gender Issues. 2016 Mar;33(1):53–68. ↵

- Baumgartner SE, Valkenburg PM, Peter J. Unwanted online sexual solicitation and risky sexual online behavior across the lifespan. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2010 Nov;31(6):439–47. ↵

- Black PJ, Wollis M, Woodworth M, Hancock JT. A linguistic analysis of grooming strategies of online child sex offenders: Implications for our understanding of predatory sexual behavior in an increasingly computer-mediated world. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2015 Jun;44:140–9. ↵

- Murphy M, Bennett N, Kottke M. Development and Pilot Test of a Commercial Sexual Exploitation Prevention Tool: A Brief Report. Violence and Victims; New York. 2016;31(1):103–10. ↵

- Whittle H, Hamilton-Giachritsis C, Beech A, Collings G. A review of young people’s vulnerabilities to online grooming. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2013 Jan;18(1):135–46. ↵

- Anderson M. Parents, Teens and Digital Monitoring [Internet]. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. 2016 [cited 2016 May 22]. Available from: http://www.pewinternet.org/2016/01/07/parents-teens-and-digital-monitoring/ ↵

- Crossler R, Belanger F, Hiller J, Aggarwal P, Channakeshava K, Bian K, et al. Parents and the Internet: Privacy Awareness, Practices, and Control. In 2007. ↵

- Eastin MS, Greenberg BS, Hofschire L. Parenting the Internet. Journal of Communication. 2006;56(3):486–504. ↵

- Kirwil L. Parental Mediation Of Children’s Internet Use In Different European Countries. Journal of Children and Media. 2009 Nov 1;3(4):394–409. ↵

- Bryce J, Fraser J. The role of disclosure of personal information in the evaluation of risk and trust in young peoples’ online interactions. Computers in Human Behavior. 2014 Jan;30:299–306. ↵

- Staksrud E, Livingstone S. CHILDREN AND ONLINE RISK: Powerless victims or resourceful participants? Information, Communication & Society. 2009 Apr;12(3):364–87. ↵

- Pater JA, Miller AD, Mynatt ED. This Digital Life: A Neighborhood-Based Study of Adolescents’ Lives Online. In ACM Press; 2015. p. 2305–14. ↵

- Tidball S, Zheng M, Creswell J. Buying Sex On-Line from Girls: NGO Representatives, Law Enforcement Officials, and Public Officials Speak out About Human Trafficking-A Qualitative Analysis. Gender Issues. 2016 Mar;33(1):53–68. ↵

- Ebrahimi M, Suen CY, Ormandjieva O. Detecting predatory conversations in social media by deep Convolutional Neural Networks. Digital Investigation. 2016 Sep;18:33–49. ↵

- Laorden C, Galan-Garcia P, Santos I, Sanz B, Nieves J, Bringas PG, et al. Negobot: Detecting paedophile activity with a conversational agent based on game theory. Logic Journal of IGPL. 2015 Feb 1;23(1):17–30. ↵

- Martellozzo E. Policing online child sexual abuse – the British experience. European Journal of policing Studies. 2015 Oct 6;3(1):32–52. ↵

- Wolak J, Finkelhor D. Are Crimes by Online Predators Different From Crimes by Sex Offenders Who Know Youth In-Person? Journal of Adolescent Health. 2013 Dec;53(6):736–41. ↵

- Martellozzo E. Policing online child sexual abuse – the British experience. European Journal of policing Studies. 2015 Oct 6;3(1):32–52. ↵

- Whittle HC, Hamilton-Giachritsis CE, Beech AR. “Under His Spell”: Victims’ Perspectives of Being Groomed Online. Social Sciences. 2014 Aug 12;3(3):404–26. ↵

- Williams A. Child sexual victimisation: ethnographic stories of stranger and acquaintance grooming. Journal of Sexual Aggression. 2015 Mar;21(1):28–42. ↵

- Razi A, Badillo-Urquiola K, Wisniewski PJ. Let’s Talk about Sext: How Adolescents Seek Support and Advice about Their Online Sexual Experiences. In: Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems [Internet]. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2020 [cited 2020 Oct 20]. p. 1–13. (CHI ’20). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1145/3313831.3376400 ↵

- Pujazon-Zazik MA, Manasse SM, Orrell-Valente JK. Adolescents’ Self-presentation on a Teen Dating Web Site: A Risk-Content Analysis. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012 May;50(5):517–20. ↵

- Doornwaard SM, Bickham DS, Rich M, Vanwesenbeeck I, van den Eijnden RJJM, ter Bogt TFM. Sex-Related Online Behaviors and Adolescents’ Body and Sexual Self-Perceptions. PEDIATRICS. 2014 Dec 1;134(6):1103–10. ↵

- Dowdell EB. Risky Internet Behaviors of Middle-School Students: Communication With Online Strangers and Offline Contact. CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing. 2011 Jun;29(6):352–9. ↵

- Wells M, Mitchell KJ. How Do High-Risk Youth Use the Internet? Characteristics and Implications for Prevention. Child Maltreatment. 2008 Feb 25;13(3):227–34. ↵

- Wisniewski P, Xu H, Rosson MB, Perkins DF, Carroll JM. Dear Diary: Teens Reflect on Their Weekly Online Risk Experiences. In: Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems [Internet]. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2016 [cited 2017 May 25]. p. 3919–30. (CHI ’16). Available from: http://doi.acm.org/10.1145/2858036.2858317 ↵

- Jones LM, Mitchell KJ, Finkelhor D. Trends in Youth Internet Victimization: Findings From Three Youth Internet Safety Surveys 2000–2010. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012 Feb 1;50(2):179–86. ↵

- Oksanen A, Näsi M, Minkkinen J, Keipi T, Kaakinen M, Räsänen P. Young people who access harm-advocating online content: A four-country survey. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace [Internet]. 2016 Jul 1 [cited 2021 Feb 12];10(2). Available from: https://cyberpsychology.eu/article/view/6179 ↵

- Bohra AS. Patterns of Internet Usage Among Youths In India [Internet]. Social Media Matters. [cited 2021 Feb 25]. Available from: https://www.socialmediamatters.in/patterns-of-internet-usage-among-youths-in-india ↵

- Wisniewski P, Xu H, Rosson MB, Perkins DF, Carroll JM. Dear Diary: Teens Reflect on Their Weekly Online Risk Experiences. In: Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems [Internet]. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2016 [cited 2017 May 25]. p. 3919–30. (CHI ’16). Available from: http://doi.acm.org/10.1145/2858036.2858317 ↵

- Rostad WL, Gittins-Stone D, Huntington C, Rizzo CJ, Pearlman D, Orchowski L. The Association Between Exposure to Violent Pornography and Teen Dating Violence in Grade 10 High School Students. Arch Sex Behav. 2019 Oct 1;48(7):2137–47. ↵

- Rodenhizer KAE, Edwards KM. The Impacts of Sexual Media Exposure on Adolescent and Emerging Adults’ Dating and Sexual Violence Attitudes and Behaviors: A Critical Review of the Literature. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2019 Oct 1;20(4):439–52. ↵

- Dyson MP, Hartling L, Shulhan J, Chisholm A, Milne A, Sundar P, et al. A Systematic Review of Social Media Use to Discuss and View Deliberate Self-Harm Acts. PLOS ONE. 2016 May 18;11(5):e0155813. ↵

- Verheijen GP, Burk WJ, Stoltz SEMJ, Berg YHM van den, Cillessen AHN. Friendly fire: Longitudinal effects of exposure to violent video games on aggressive behavior in adolescent friendship dyads. Aggressive Behavior. 2018;44(3):257–67. ↵

- Ferguson CJ, Wang JCK. Aggressive Video Games are Not a Risk Factor for Future Aggression in Youth: A Longitudinal Study. J Youth Adolescence. 2019 Aug 1;48(8):1439–51. ↵

- Markey PM, Ferguson CJ. Moral Combat: Why the War on Violent Video Games Is Wrong. BenBella Books, Inc.; 2017. 218 p. ↵

- Peter J, Valkenburg P. Adolescents’ exposure to sexually explicit material on the Internet. Communication Research. 2006;33(2):178–204. ↵

- Ybarra ML, Mitchell KJ. Exposure to Internet Pornography among Children and Adolescents: A National Survey. CyberPsychology & Behavior. 2005 Oct 1;8(5):473–86. ↵

- Bőthe B, Vaillancourt-Morel M-P, Bergeron S, Demetrovics Z. Problematic and Non-Problematic Pornography Use Among LGBTQ Adolescents: a Systematic Literature Review. Curr Addict Rep. 2019 Dec 1;6(4):478–94. ↵

- Oksanen A, Näsi M, Minkkinen J, Keipi T, Kaakinen M, Räsänen P. Young people who access harm-advocating online content: A four-country survey. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace [Internet]. 2016 Jul 1 [cited 2021 Feb 12];10(2). Available from: https://cyberpsychology.eu/article/view/6179 ↵

- Wisniewski P, Jia H, Wang N, Zheng S, Xu H, Rosson MB, et al. Resilience Mitigates the Negative Effects of Adolescent Internet Addiction and Online Risk Exposure. In: Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems [Internet]. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2015 [cited 2016 Sep 21]. p. 4029–38. (CHI ’15). Available from: http://doi.acm.org/10.1145/2702123.2702240 ↵

- Wisniewski P, Jia H, Xu H, Rosson MB, Carroll JM. “Preventative” vs. “Reactive”: How Parental Mediation Influences Teens’ Social Media Privacy Behaviors. In ACM Press; 2015. p. 302–16. ↵

- Mitchell KJ, Finkelhor D, Wolak J. Protecting youth online: Family use of filtering and blocking software. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005 Jul 1;29(7):753–65. ↵

- Ybarra ML, Finkelhor D, Mitchell KJ, Wolak J. Associations between blocking, monitoring, and filtering software on the home computer and youth-reported unwanted exposure to sexual material online. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2009 Dec;33(12):857–69. ↵

- Ghosh AK, Badillo-Urquiola K, Guha S, LaViola JJ, Wisniewski PJ. Safety vs. Surveillance: What Children Have to Say about Mobile Apps for Parental Control. In the Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI). 2018; ↵

- Ghosh AK, Badillo-Urquiola K, Rosson MB, Xu H, Carroll J, Wisniewski P. A Matter of Control or Safety? Examining Parental Use of Technical Monitoring Apps on Teens’ Mobile Devices. In the Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI). 2018; ↵

- Duerager A, Livingstone S. How can parents support children’s internet safety? [Internet]. 2012. Available from: http://www.lse.ac.uk/media@lse/research/EUKidsOnline/EU%20Kids%20III/Reports/ParentalMediation.pdf ↵

- Erickson LB, Wisniewski P, Xu H, Carroll JM, Rosson MB, Perkins DF. The boundaries between: Parental involvement in a teen’s online world. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology. 2015;n/a-n/a. ↵

- Ghosh AK, Badillo-Urquiola K, Guha S, LaViola JJ Jr, Wisniewski PJ. Safety vs. Surveillance: What Children Have to Say about Mobile Apps for Parental Control. In: Proceedings of the 2018 ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Montréal, Canada: ACM; 2018. ↵

- Shin W, Ismail N. Exploring the role of parents and peers in young adolescents’ risk taking on social networking sites. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2014 Sep;17(9):578–83. ↵

- Ghosh AK, Badillo-Urquiola K, Rosson MB, Xu H, Carroll JM, Wisniewski PJ. A Matter of Control or Safety?: Examining Parental Use of Technical Monitoring Apps on Teens’ Mobile Devices. In: Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems [Internet]. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2018 [cited 2018 May 28]. p. 194:1-194:14. (CHI ’18). Available from: http://doi.acm.org/10.1145/3173574.3173768 ↵

- Wisniewski P, Xu H, Rosson MB, Carroll JM. Parents Just Don’t Understand: Why Teens Don’t Talk to Parents About Their Online Risk Experiences. In: Proceedings of the 2017 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing [Internet]. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2017 [cited 2017 May 25]. p. 523–40. (CSCW ’17). Available from: http://doi.acm.org/10.1145/2998181.2998236 ↵

- Blau I. Comparing online opportunities and risks among Israeli children and youth Hebrew and Arabic speakers. New Review of Hypermedia and Multimedia. 2014 Oct 2;20(4):281–99. ↵

- Wisniewski P, Jia H, Xu H, Rosson MB, Carroll JM. “Preventative” vs. “Reactive”: How Parental Mediation Influences Teens’ Social Media Privacy Behaviors. In ACM Press; 2015. p. 302–16. ↵

- Christofides E, Muise A, Desmarais S. Hey Mom, What’s on Your Facebook? Comparing Facebook Disclosure and Privacy in Adolescents and Adults. Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2012 Jan 1;3(1):48–54. ↵

- Mesch GS, Beker G. Are Norms of Disclosure of Online and Offline Personal Information Associated with the Disclosure of Personal Information Online? Human Communication Research. 2010 Sep 16;36(4):570–92. ↵

- Jambunathan S, Counselman K. Parenting Attitudes of Asian Indian Mothers Living in the United States and in India. Early Child Development and Care. 2002 Dec 1;172(6):657–62. ↵

- Lwin M O, Stanaland AJS, Miyazaki AD. Protecting children’s privacy online: How parental mediation strategies affect website safeguard effectiveness. Journal of Retailing. 2008 Jun;84(2):205–17. ↵

- Wolak J, Finkelhor D, Mitchell KJ, Ybarra ML. Online “predators” and Their Victims: Myths, Realities, and Implications for Prevention and Treatment. Psychology of Violence. 2010 Aug 1;1(S):13–35. ↵

- Rice E, Winetrobe H, Holloway IW, Montoya J, Plant A, Kordic T. Cell Phone Internet Access, Online Sexual Solicitation, Partner Seeking, and Sexual Risk Behavior Among Adolescents. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2015 Apr;44(3):755–63. ↵

- Doornwaard SM, ter Bogt TFM, Reitz E, van den Eijnden RJJM. Sex-Related Online Behaviors, Perceived Peer Norms and Adolescents’ Experience with Sexual Behavior: Testing an Integrative Model. Zeeb H, editor. PLOS ONE. 2015 Jun 18;10(6):e0127787. ↵

- Doornwaard SM, Bickham DS, Rich M, Vanwesenbeeck I, van den Eijnden RJJM, ter Bogt TFM. Sex-Related Online Behaviors and Adolescents’ Body and Sexual Self-Perceptions. PEDIATRICS. 2014 Dec 1;134(6):1103–10. ↵

- Doornwaard SM, ter Bogt TFM, Reitz E, van den Eijnden RJJM. Sex-Related Online Behaviors, Perceived Peer Norms and Adolescents’ Experience with Sexual Behavior: Testing an Integrative Model. Zeeb H, editor. PLOS ONE. 2015 Jun 18;10(6):e0127787. ↵

- Blau I. Comparing online opportunities and risks among Israeli children and youth Hebrew and Arabic speakers. New Review of Hypermedia and Multimedia. 2014 Oct 2;20(4):281–99. ↵

- Leung L, Lee PSN. The influences of information literacy, internet addiction and parenting styles on internet risks. New Media & Society. 2012 Feb 1;14(1):117–36. ↵

- Lee S-J, Chae Y-G. Balancing Participation and Risks in Children’s Internet Use: The Role of Internet Literacy and Parental Mediation. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2012 May;15(5):257–62. ↵

- Leung L, Lee PSN. The influences of information literacy, internet addiction and parenting styles on internet risks. New Media & Society. 2012 Feb 1;14(1):117–36. ↵

- Forte A, Dickard M, Magee R, Agosto DE. What do teens ask their online social networks?: social search practices among high school students. In ACM Press; 2014. p. 28–37. ↵

- Agosto DE, Abbas J. High school seniors’ social network and other ICT use preferences and concerns. Proceedings of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. 2010;47(1):1–10. ↵

- Feng Y, Xie W. Teens’ concern for privacy when using social networking sites: An analysis of socialization agents and relationships with privacy-protecting behaviors. Computers in Human Behavior. 2014 Apr;33:153–62. ↵

- Leung L, Lee PSN. The influences of information literacy, internet addiction and parenting styles on internet risks. New Media & Society. 2012 Feb 1;14(1):117–36. ↵

- Pujazon-Zazik MA, Manasse SM, Orrell-Valente JK. Adolescents’ Self-presentation on a Teen Dating Web Site: A Risk-Content Analysis. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012 May;50(5):517–20. ↵

- Rice E, Winetrobe H, Holloway IW, Montoya J, Plant A, Kordic T. Cell Phone Internet Access, Online Sexual Solicitation, Partner Seeking, and Sexual Risk Behavior Among Adolescents. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2015 Apr;44(3):755–63. ↵

- Ibanez M. Virtual Red Light Districts: Detecting Covert Networks and Sex Trafficking Circuits in the U.S. ProQuest LLC; 2015. ↵

- Wisniewski P, Jia H, Xu H, Rosson MB, Carroll JM. “Preventative” vs. “Reactive”: How Parental Mediation Influences Teens’ Social Media Privacy Behaviors. In ACM Press; 2015. p. 302–16. ↵

- Pinter AT, Wisniewski PJ, Xu H, Rosson MB, Caroll JM. Adolescent Online Safety: Moving Beyond Formative Evaluations to Designing Solutions for the Future. In: Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Interaction Design and Children [Internet]. Stanford California USA: ACM; 2017 [cited 2020 Nov 4]. p. 352–7. Available from: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3078072.3079722 ↵

- Wisniewski P, Jia H, Wang N, Zheng S, Xu H, Rosson MB, et al. Resilience Mitigates the Negative Effects of Adolescent Internet Addiction and Online Risk Exposure. In: Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems [Internet]. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2015 [cited 2016 Sep 21]. p. 4029–38. (CHI ’15). Available from: http://doi.acm.org/10.1145/2702123.2702240 ↵

- Pinter AT, Wisniewski PJ, Xu H, Rosson MB, Caroll JM. Adolescent Online Safety: Moving Beyond Formative Evaluations to Designing Solutions for the Future. In: Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Interaction Design and Children [Internet]. Stanford California USA: ACM; 2017 [cited 2020 Nov 4]. p. 352–7. Available from: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3078072.3079722 ↵

- Wisniewski P. The Privacy Paradox of Adolescent Online Safety: A Matter of Risk Prevention or Risk Resilience? IEEE Security & Privacy. 2018 Apr;16(2):86–90. ↵

- Ghosh AK, Badillo-Urquiola K, Rosson MB, Xu H, Carroll J, Wisniewski P. A Matter of Control or Safety? Examining Parental Use of Technical Monitoring Apps on Teens’ Mobile Devices. In the Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI). 2018; ↵

- Rice E, Winetrobe H, Holloway IW, Montoya J, Plant A, Kordic T. Cell Phone Internet Access, Online Sexual Solicitation, Partner Seeking, and Sexual Risk Behavior Among Adolescents. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2015 Apr;44(3):755–63. ↵

- Ghosh AK, Badillo-Urquiola K, Rosson MB, Xu H, Carroll J, Wisniewski P. A Matter of Control or Safety? Examining Parental Use of Technical Monitoring Apps on Teens’ Mobile Devices. In the Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI). 2018; ↵

- Wisniewski P, Jia H, Wang N, Zheng S, Xu H, Rosson MB, et al. Resilience Mitigates the Negative Effects of Adolescent Internet Addiction and Online Risk Exposure. In: Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems [Internet]. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2015 [cited 2016 Sep 21]. p. 4029–38. (CHI ’15). Available from: http://doi.acm.org/10.1145/2702123.2702240 ↵

- Wolak J, Finkelhor D, Mitchell KJ, Ybarra ML. Online “predators” and Their Victims: Myths, Realities, and Implications for Prevention and Treatment. Psychology of Violence. 2010 Aug 1;1(S):13–35. ↵

- Wisniewski P, Jia H, Wang N, Zheng S, Xu H, Rosson MB, et al. Resilience Mitigates the Negative Effects of Adolescent Internet Addiction and Online Risk Exposure. In: Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems [Internet]. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2015 [cited 2016 Sep 21]. p. 4029–38. (CHI ’15). Available from: http://doi.acm.org/10.1145/2702123.2702240 ↵

- Wisniewski P, Xu H, Rosson MB, Perkins DF, Carroll JM. Dear Diary: Teens Reflect on Their Weekly Online Risk Experiences. In: Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems [Internet]. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2016 [cited 2017 May 25]. p. 3919–30. (CHI ’16). Available from: http://doi.acm.org/10.1145/2858036.2858317 ↵

- Child Rights and You (CRY). Online Safety and Internet Addiction (A Study Conducted Amongst Adolescents in Delhi-NCR). New Delhi; 2020. ↵

- Hartikainen H, Iivari N, Kinnula M. Should We Design for Control, Trust or Involvement?: A Discourses Survey about Children’s Online Safety. In: Proceedings of the The 15th International Conference on Interaction Design and Children – IDC ’16 [Internet]. Manchester, United Kingdom: ACM Press; 2016 [cited 2020 Nov 10]. p. 367–78. Available from: http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?doid=2930674.2930680 ↵

- Hartikainen H, Iivari N, Kinnula M. Should We Design for Control, Trust or Involvement?: A Discourses Survey about Children’s Online Safety. In: Proceedings of the The 15th International Conference on Interaction Design and Children – IDC ’16 [Internet]. Manchester, United Kingdom: ACM Press; 2016 [cited 2020 Nov 10]. p. 367–78. Available from: http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?doid=2930674.2930680 ↵

- boyd danah. It’s Complicated: The Social Lives of Networked Teens. 1 edition. New Haven: Yale University Press; 2014. 296 p. ↵

- Anderson M, Jiang J. Teens, Social Media & Technology 2018 [Internet]. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. 2018 [cited 2018 Jul 15]. Available from: http://www.pewinternet.org/2018/05/31/teens-social-media-technology-2018/ ↵

- Ghosh AK, Wisniewski P. Understanding User Reviews of Adolescent Mobile Safety Apps: A Thematic Analysis. In: Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Supporting Group Work [Internet]. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2016 [cited 2017 Apr 26]. p. 417–20. (GROUP ’16). Available from: http://doi.acm.org/10.1145/2957276.2996283 ↵

- Collier A. Less parental control, more support of kids’ self-regulation: Study [Internet]. ConnectSafely. 2014 [cited 2017 Jul 18]. Available from: http://www.connectsafely.org/less-parental-control-more-support-of-kids-self-regulation-study/ ↵

- Law DM, Shapka JD, Olson BF. To control or not to control? Parenting behaviours and adolescent online aggression. Computers in Human Behavior. 2010 Nov 1;26(6):1651–6. ↵

- Schiano DJ, Burg C. Parental Controls: Oxymoron and Design Opportunity. In: HCI International 2017 – Posters’ Extended Abstracts [Internet]. Springer, Cham; 2017 [cited 2017 Jul 18]. p. 645–52. (Communications in Computer and Information Science). Available from: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-58753-0_91 ↵

- NSF Award Search: Award#1618153 – TWC SBE: Small: Helping Teens and Parents Negotiate Online Privacy and Safety [Internet]. [cited 2017 Jul 31]. Available from: https://www.nsf.gov/awardsearch/showAward?AWD_ID=1618153&HistoricalAwards=false ↵

- Wisniewski P, Ghosh AK, Rosson MB, Xu H, Carroll JM. Parental Control vs. Teen Self-Regulation: Is there a middle ground for mobile online safety? In: Proceedings of the 20th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing. Portland, OR, USA: ACM; 2017. ↵

- Wisniewski P, Ghosh AK, Rosson MB, Xu H, Carroll JM. Parental Control vs. Teen Self-Regulation: Is there a middle ground for mobile online safety? In: Proceedings of the 20th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing. Portland, OR, USA: ACM; 2017. ↵

- Duerager A, Livingstone S. How can parents support children’s internet safety? [Internet]. 2012. Available from: http://www.lse.ac.uk/media@lse/research/EUKidsOnline/EU%20Kids%20III/Reports/ParentalMediation.pdf ↵

- Khurana A, Bleakley A, Jordan AB, Romer D. The protective effects of parental monitoring and internet restriction on adolescents’ risk of online harassment. J Youth Adolesc. 2015 May;44(5):1039–47. ↵

- Lee S-J, Chae Y-G. Balancing participation and risks in children’s Internet use: the role of internet literacy and parental mediation. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2012 May;15(5):257–62. ↵

- Livingstone S, Helsper EJ. Parental Mediation of Children’s Internet Use. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 2008;52(4):581–99. ↵

- boyd danah. It’s Complicated: The Social Lives of Networked Teens. 1 edition. New Haven: Yale University Press; 2014. 296 p. ↵

- Erickson LB, Wisniewski P, Xu H, Carroll JM, Rosson MB, Perkins DF. The boundaries between: Parental involvement in a teen’s online world. J Assn Inf Sci Tec. 2016 Jun 1;67(6):1384–403. ↵

- Petronio S. Communication privacy management theory: What do we know about family privacy regulation? Journal of Family Theory & Review. 2010;2(3):175–96. ↵

- Petronio S. Privacy binds in family interactions: The case of parental privacy invasion. In: Spitzberg WRCBH, editor. The dark side of interpersonal communication. Hillsdale, NJ, England: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1994. p. 241–57. (LEA’s communication series.). ↵

- Valkenburg PM, Krcmar M, Peeters AL, Marseille NM. Developing A Scale to Assess Three Styles of Television Mediation: “Instructive Mediation,” “Restrictive Mediation,” and “Social Coviewing.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 1999;43(1):52–66. ↵

- Eastin MS, Greenberg BS, Hofschire L. Parenting the Internet. Journal of Communication. 2006;56(3):486–504. ↵

- Duerager A, Livingstone S. How can parents support children’s internet safety? [Internet]. 2012. Available from: http://www.lse.ac.uk/media@lse/research/EUKidsOnline/EU%20Kids%20III/Reports/ParentalMediation.pdf ↵

- Livingstone S, Helsper EJ. Parental Mediation of Children’s Internet Use. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 2008;52(4):581–99. ↵

- Mesch GS. Parental Mediation, Online Activities, and Cyberbullying. CyberPsychology & Behavior. 2009 Aug;12(4):387–93. ↵

- Wisniewski P, Ghosh AK, Rosson MB, Xu H, Carroll JM. Parental Control vs. Teen Self-Regulation: Is there a middle ground for mobile online safety? In: Proceedings of the 20th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing. Portland, OR, USA: ACM; 2017. ↵

- Ghosh AK, Badillo-Urquiola K, Guha S, LaViola JJ, Wisniewski PJ. Safety vs. Surveillance: What Children Have to Say about Mobile Apps for Parental Control. In the Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI). 2018; ↵

- Pinter AT, Wisniewski PJ, Xu H, Rosson MB, Caroll JM. Adolescent Online Safety: Moving Beyond Formative Evaluations to Designing Solutions for the Future. In: Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Interaction Design and Children [Internet]. Stanford California USA: ACM; 2017 [cited 2020 Nov 4]. p. 352–7. Available from: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3078072.3079722 ↵

- Mesch GS, Beker G. Are Norms of Disclosure of Online and Offline Personal Information Associated with the Disclosure of Personal Information Online? Human Communication Research. 2010 Sep 16;36(4):570–92. ↵

- Shin W, Huh J, Faber RJ. Tweens’ Online Privacy Risks and the Role of Parental Mediation. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 2012 Oct;56(4):632–49. ↵

- Wisniewski P, Jia H, Xu H, Rosson MB, Carroll JM. “Preventative” vs. “Reactive”: How Parental Mediation Influences Teens’ Social Media Privacy Behaviors. In ACM Press; 2015. p. 302–16. ↵

- Mitchell K, Jones L, Finkelhor D, Wolak J. Trends in Unwanted Online Experiences and Sexting : Final Report. Crimes Against Children Research Center [Internet]. 2014 Feb 1; Available from: http://scholars.unh.edu/ccrc/49 ↵

- Li Q. A cross-cultural comparison of adolescents’ experience related to cyberbullying. Educational Research. 2008 Sep;50(3):223–34. ↵

- Näsi M, Räsänen P, Oksanen A, Hawdon J, Keipi T, Holkeri E. Association between online harassment and exposure to harmful online content: A cross-national comparison between the United States and Finland. Computers in Human Behavior. 2014 Dec;41:137–45. ↵

- Livingstone S, Kirwil L, Ponte C, Staksrud E. In their own words: What bothers children online? European Journal of Communication. 2014;29(3):271–88. ↵

- Baumgartner SE, Sumter SR, Peter J, Valkenburg PM, Livingstone S. Does country context matter? Investigating the predictors of teen sexting across Europe. Computers in Human Behavior. 2014 May;34:157–64. ↵

- Menesini E, Nocentini A, Palladino BE, Frisén A, Berne S, Ortega-Ruiz R, et al. Cyberbullying Definition Among Adolescents: A Comparison Across Six European Countries. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2012 Sep;15(9):455–63. ↵

- Livingstone S, Kirwil L, Ponte C, Staksrud E. In their own words: What bothers children online? European Journal of Communication. 2014;29(3):271–88. ↵

- Baumgartner SE, Sumter SR, Peter J, Valkenburg PM, Livingstone S. Does country context matter? Investigating the predictors of teen sexting across Europe. Computers in Human Behavior. 2014 May;34:157–64. ↵

- EU Kids Online. www.eukidsonline.net [Internet]. London School of Economics and Political Science. [cited 2020 Oct 31]. Available from: https://www.lse.ac.uk/media-and-communications/research/research-projects/eu-kids-online/home.aspx ↵

- Jambunathan S, Counselman K. Parenting Attitudes of Asian Indian Mothers Living in the United States and in India. Early Child Development and Care. 2002 Dec 1;172(6):657–62. ↵

- Sandhu GK, Sharma V. Social Withdrawal and Social Anxiety in Relation to Stylistic Parenting Dimensions in the Indian Cultural Context. Research in Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Research in Psychology and Behavioral Sciences. 2015 Dec 29;3(3):51–9. ↵

- Brody GH, Flor DL. Maternal Resources, Parenting Practices, and Child Competence in Rural, Single-Parent African American Families. Child Development. 1998 Jun 1;69(3):803–16. ↵

- Greening L, Stoppelbein L, Luebbe A. The Moderating Effects of Parenting Styles on African-American and Caucasian Children’s Suicidal Behaviors. J Youth Adolescence. 2010 Apr 1;39(4):357–69. ↵

- Child Online Protection in India [Internet]. International Centre for Missing & Exploited Children. 2016 [cited 2020 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.icmec.org/child-online-protection-in-india/ ↵

- Child Online Protection in India [Internet]. International Centre for Missing & Exploited Children. 2016 [cited 2020 Oct 8]. Available from: https://www.icmec.org/child-online-protection-in-india/ ↵

- Garg R, Sengupta S. “When you can do it, why can’t I?”: Racial and Socioeconomic Differences in Family Technology Use and Non-Use. Proc ACM Hum-Comput Interact. 2019 Nov 7;3(CSCW):63:1-63:22. ↵