Chapter 1: Introduction

Drishti Sharma; Nandini Sharma; and Ritika Bakshi

ABSTRACT

As access to digital technologies increases rapidly worldwide, it brings risks alongside enormous benefits, especially for the children and adolescents. The magnitude of online risks like cyberbullying is growing across the world, and India is no exception. Studies across the globe suggest that use of electronic communication technologies has a significant impact on the mental, physical and social health of adolescents. Therefore, understanding and mitigating online risks is crucial. This requires a shared understanding of online risks amongst the key stakeholders to work collaboratively to promote well-being of youth in an increasingly digital world. The socio-ecological model provides a framework that can organize important protective and risk factors for preventing cyberbullying and other online threats. These factors are located within multiple systems that constantly interact, broadly involving the youth, their families, peers and schools, communities, and society.

In this chapter, we introduce cyberbullying and other online risks faced by adolescents as well as the overall opportunities offered by digital media, particularly in the developing world. By mitigating the threats, we can avoid the increasing digital divide and ensure continued healthy youth development. We explore what cyberbullying is, the magnitude of the problem, and its harmful impacts. We will also briefly introduce the landscape we intend to cover through this book using the framework of the socio-ecological model. Our goal is to make this information accessible for the use of Indian stakeholders who are invested in preventing cyberbullying and promoting adolescents’ digital citizenship. Throughout the book, we draw insights from scientific work across the globe and apply them to India’s current policy ecosystem.

INDIAN CONTEXT

India is home to 1.3 billion people.[1] It has the largest adolescent population globally.[2] According to the 2011 census, 83% of India’s population lives in rural areas. Despite the record economic growth, literacy remains low. In the 2011 census, 73% of the population was literate. Literacy for girls and women is much lower (64.6%) as compared to boys and men (80.9%).

The World Bank classifies India as a low-middle income economy. Its health system is constrained, with a reported 0.53 hospital beds per 1000 people in 2017.[3] Further, it falls in the low density of healthcare workers, with 0.3 psychiatrists and 0.05 psychologists per 100,000 people.[4]

As with many other low-income countries, in India, the digital revolution skipped the phase of computers and laptops. This means that many households owned mobile devices as their first digital device. In India, in 2019, one in three individuals of age 12 years and above had access to internet. Of these users, 32% were within the age group of 12-19 years.[5] This suggests that adolescents are disproportionately more likely to have access to the Internet compared to adults and older adults. Also, our focus groups with stakeholders revealed that the sharing of electronic communication devices is prevalent within Indian families. The latest IAMAI report stated, “While internet users grew by 4% in urban India reaching 323 million users in 2020, digital adoption continues to be propelled by rural India – registering a 13% growth in internet users over the past year”.[6]

Digital technology has already changed the world. As more and more children have access to the technology, it is increasingly changing the dynamics of the childhood as well. If leveraged strategically and made universally accessible, digital technology can be a game changer for children who are left behind.

In this book we make a case for faster action, focused investment and greater cooperation to protect children from the harms of a more connected world. Along with this, we also focus on harnessing the opportunities of the digital age to benefit every child.[7] Strategic planning is critically relevant for India. If action is not taken soon enough, digital divide will continue to magnify the prevailing economic gaps. This will in turn amplify the advantages of children from wealthier backgrounds and fail to deliver opportunities to the poorest and the underprivileged children.

OPPORTUNITIES OFFERED BY DIGITAL MEDIA

Internet connectivity has ushered in knowledge transfer at a scale which was earlier unknown and unimaginable. Bill Gates once said, “The internet is becoming the town square for the global village of tomorrow.”

Children and adolescents around the world have embraced technology with ease. They have created new spaces for social interactions. Indeed, the advances have been so rapid that parents and caregivers often struggle to keep up.[8] Digitalization offers seemingly limitless opportunities. It allows children to connect with friends and make decisions for themselves. It gives access to education, which is especially important for those living in remote or marginalized areas. Countless stories and examples illustrate how children worldwide have utilized the digital technologies to learn, socialize, and shape their paths into adulthood. For instance, in Brazil, the Amazon state government’s educational initiative has provided educational content since 2007 to children and youth living remotely. Classes are taught by teachers in rural communities using satellite television. In addition to printed resources, they also have access to digital textbooks and other educational resources through the internet.[9]

Skills and vocational training programs are yet another domain where digital connectivity is opening opportunities to learn. This is particularly true for children hailing from very low- income families. Such children often leave formal schooling to earn livelihood. In Kampala, Uganda, the ‘Women in Technology’ organization offers digital vocational training for young women in under-served communities. The organization teaches young women digital, leadership and life skills. Girls attending the program have reported learning entrepreneurship skills and the use of the internet to identify their business opportunities.[10] Such initiatives of providing access to technology strategically has fostered better educational and economic opportunities to the vulnerable communities.

In addition, digital access is vital during emergencies such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Online web-based learning or e-learning played a major role in making the teaching-learning process more student-centered, innovative, and flexible, when the schools and colleges were shut down across the world.[11]

DIGITAL ACCESS DIVIDE

Greater online connectivity has opened new avenues for civic engagement, social inclusion and other opportunities, with the potential to break cycles of poverty and disadvantage. However, disparities in access to internet services vary between groups depending upon income, family education and literacy, and urbanicity/rurality. To be specific, 81 percent of people in developed countries use the internet, while only 40 percent of the people use internet in developing countries. In least developing countries the number is even lower at 15 percent.[12] GSM Association (GSMA) survey in 2015 found that in low- and middle-income countries, various socio-economic and cultural barriers tend to keep girls and women from using mobile phones.[13] Such barriers include social norms, education levels, lack of technical literacy and decision-making, employment and income, etc. The National Family Health Survey-5 (NFHS5) reports suggest that gender disparities in usage of internet in India are greater across the rural areas than urban regions. These findings highlight that the gender disparities in the offline world are significantly reflected in the online world as well.[14]

But unless we reduce the disparities, digital technology may create new divides that prevent children from fulfilling their potential. If we don’t act now to keep pace with rapid change, online risks may make vulnerable children more susceptible to exploitation, abuse and even trafficking. It may also result in more subtle threats to their well-being.[15]

DIGITAL RISKS AND SAFETY

Online risks among adolescents are of four kinds[16]—

- Cyberbullying or online harassment

- Sexual solicitation and risky sexual behaviors

- Exposure to explicit content

- Information breaches and privacy violations

We elaborate on cyberbullying prevention and response in Chapter 1, 2, 3 and 4. Further, in Chapter 5, we place cyberbullying in the broader context of online digital safety. In Chapter 6, we identify the possible platforms in the Indian policy landscape that can be leveraged to address the situation.

Throughout the book, we make a case for using a common approach of resilience-based frameworks to address all kinds of digital risks. Digital resilience means empowering children to become active, aware, and ethical digital citizens. It requires building capacity to safely navigate the digital world.[17] This approach strikes a balance between teen’s privacy and online safety through active communication and fostering trust between parents and children. It stands in contrast to the current “risk-averse” approach to online safety. This approach emphasizes on protecting adolescents from being exposed to online risks. The underlying fear often culminates in actions that restrict access to electronic communication technologies for youth. It often includes privacy-invasive monitoring. We suggest that this response is ineffective because no matter how much restrictions we place, just as in everyday life, a zero-risk digital environment is unattainable. We have already elaborated on how online interactions can provide social support, belonging, education, entertainment, and other positive conditions for healthy youth development. Online safety therefore, should maximize the benefits of the internet while mitigating some of its unintended consequences.[18]

WHAT IS CYBERBULLYING?

Bullying is a type of aggressive behavior that is traditionally defined as “intentional, repeated negative (unpleasant or hurtful) behavior by one or more persons directed against a person who has difficulty defending himself or herself.”[19] Bullying can be perpetrated in-person or via electronic means. Cyber bullying or online bullying is a form of bullying or harassment using electronic communication technologies means. It includes direct messaging particularly through social media websites, and a range of electronic applications and other websites.

Cyberbullying is often understood as an extension of in-person bullying that occurs in schools. The definition of cyberbullying has been debated, but most definitions specify that cyberbullying is some type of aggression (e.g., harassment, bullying) that occurs through electronic communication technologies.[20]

Aggression among youth includes the following forms of aggression- physical, verbal and relational (or social). Physical aggression causes or threatens to cause physical harm. It may include behaviors such as hitting, kicking, tripping, pinching, pushing or damaging property. Verbal aggression, in contrast, targets a person’s sense of self, agency, or dignity. It includes name-calling, insults, teasing, intimidation, racist remarks, or verbal abuse. Relational or social aggression targets a person’s social relationships, status, image, or reputation. It includes lying, spreading rumors or embarrassing information, making rude or disrespectful negative facial or physical gestures, cracking jokes to embarrass and humiliate someone, mimicking unkindly. It also includes causing social isolation or exclusion, encouraging others to socially exclude someone and damaging someone’s social reputation or social acceptance.[21]

Unfortunately, increased access to the internet through the unmediated use of smartphones exposes children and adolescents to many online risks. Bullying has become a part of our routine interactions on platforms such as WhatsApp, SnapChat, Twitter, Facebook, TikTok, etc. Body-shaming goes unabated; false rumors spread unchecked; and morphed pictures or videos are shared with a limitless audience. Cyberbullying also offers anonymity to the perpetrators allowing them to continue bullying without any fear of the real-world consequences. These factors, combined with the lack of monitoring and regulation in cyberspace, makes the issue more intricate and challenging to address.

Although children are aware of the damage and profound harm that cyberbullying causes, they are not always immediately conscious of the long-term consequences of their actions. Further, though they have superior technological skills, they lack awareness about the need of appropriate protective measures when it comes to sharing personal information. They may not be able to distinguish between online and offline “friends”. Adults struggle to provide support to youth too. Cyberbullying does not require the physical presence of the victim. It is, by its very nature, a hidden kind of behavior. Often adults fail to detect and address cyberbullying, particularly when they take place in spaces beyond adult supervision.[22]

Despite the growing concern, the research on cyberbullying in India is at a nascent stage. A systematic review done by Thakkar et al. in 2020 reported there were very few scientific articles on the topic for a meaningful inference.[23] As with research, the practice of cyberbullying prevention faces challenges too. The point is driven home by a report commissioned by UNICEF to understand online child safety in India in 2016. The report reveals that despite provisions in legislation and policies in India, there is a general lack of understanding of professionals, policymakers, and society of the risks and threats posed to children by information and communication technology (ICT) and social media.[24] Despite the limitation, the urgency of equipping stakeholders with information is clear. Therefore, throughout the book, we attempt to synthesize the available literature to draw actionable inferences for the Indian context.

BURDEN

With the rising internet usage, the rate of cyberbullying incidents is likely to increase in the years to come. Globally, current prevalence estimates for cyberbullying victimization range between approximately 10 and 40 percent. The wide range suggests that estimates of the burden of cyberbullying victimization varies across studies. The variation is attributed to several factors- the manner in which cyberbullying is defined (for a more detailed discussion of this issue, see Chapter 2), differences in the ages and locations of the individuals sampled, the reporting time frame being assessed (e.g., lifetime, 2 months, 6 months), and the frequency rate by which a person is classified as a perpetrator or victim (e.g., at least once, several times a week).[25] Despite the varying estimates, data consistently indicate that a considerable number of youngsters are being cyberbullied across the globe.[26]

Majority of the incidents of cyberbullying are subtle (less harmful).[27] Some, however, cross the line into unlawful or criminal behavior. For instance, cases of cyber stalking or bullying of children rose from 40 in 2018 to 140 in 2020, as reported by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) of India.[28],[29] These criminal cases essentially represent the tip of the iceberg and reports indicate an increasing trend of such episodes. Also, for every serious case reported, many relatively low-risk incidents of risk exposure go unreported. Clearly, we can respond well to these low-risk exposures by empowering teens with necessary technical and socio-emotional coping skills to avoid catastrophic consequences.[30]

The research also suggests that parents and teachers are often in the dark, unaware of bullying experiences of youth.[31] Youth who face cyberbullying, hesitate to confide in their elders or caregivers due to the perception of the lack of technical know-how amongst elders and fear of losing access to their devices.[32] Hence, surveys that measure children’s self-reports of such incidents are a valuable source of measuring the burden.

As per an Indian survey conducted in 2012, eight percent of 174 youth in Delhi ever perpetrated cyberbullying, and 17 percent reported being victimized. The percentage of boys who were victimized exceeded the percentage of girls. The rate of cyberbullying perpetration was comparable across gender. When the exposure to such events is compared with global figures, we find comparable rates across gender. We suspect that India’s cultural factors and gender roles contribute to limited access to mobile devices for girls thus resulting in lower exposure to such events. That is, limited access may explain the anomaly of higher incidence of victimization among boys.[33] However, a systematic enquiry linking gender and digital access with cyberbullying behavior is required to verify this hypothesis. Also, it is worth reiterating that lower access may drive other socio-economic disadvantages. In this case, limited access due to the risk of exposure to cyberbullying or other digital risks may result in the child losing many opportunities for growth and development.

In Ahmedabad, Gujarat, in 2017, a study was conducted on 240 respondents (120 boys and 120 girls) aged 12-17 years, from standard VII to XII. The findings indicate that nearly 14 percent of respondents reported cyberbullying in their lifetime and seven percent reported cyberbullying involvement in the last thirty days.

Likewise, Microsoft Corporation conducted the ‘Global Youth Online Behavior Survey’, in 2012 on the phenomenon of online bullying. Survey was conducted with 7,644 youth aged eight to seventeen years in twenty-five countries (approximately 300 respondents per country), including six Asian nations. Of the 25 countries surveyed, the three countries in which participants reported the highest rates of online bullying victimization were China (70%), Singapore (58%), and India (53%). Other Asian countries in the study reported the following percentages of online bullying: Malaysia, 33%; Pakistan, 26%; and Japan, 17%. The same three countries with the highest rates of online bullying victimization also reported the highest rates of having bullied someone online- China (58%), India (50%), and Singapore (46%).[34]

Further, in 2020, Child Rights and You (CRY), a Non-Governmental Organization (NGO), reported around 9.2% of 630 adolescents surveyed in Delhi-National Capital Region (NCR) had experienced cyberbullying. Half of them had not reported it to teachers or guardians of the social media companies concerned.[35]

Notably, these surveys were not representative of national-level estimates. Further information on rates disaggregated across sub-groups, e.g., gender, developmental age-groups, socio-economic class, caste, color, rural or urban residence, ethnicities or region of origin, language, disability, sexual orientation, school-going or out-of-school is yet to be studied.

IMPACT

Some victims of cyberbullying are not upset or disturbed. However, cyberbullying is often associated with many emotional and psychological conditions, including stress, lower self-esteem, and life satisfaction,[36] with far-reaching effects during adolescence and adulthood. Most of the scientific literature reporting the impact of cyberbullying is cross-sectional (i.e., the behavior and its impact is reported at the same instance among individuals), and to establish temporal relationships and potential causal inferences, more longitudinal studies (where subjects are followed over time to study the outcome of a certain behavior) are required. Like the burden estimates, evidence from representative surveys measuring the impact of cyberbullying among adolescents is nearly absent in the Indian context. Therefore, we would try to draw from global literature and as much as possible from comparable regions.

In 2014, Kowalski et al. published a meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth, including 131 studies mainly from the developed world. These studies have linked cyberbullying involvement as a victim or perpetrator to substance use; mental health symptoms, e.g., anxiety and depression; decreased self-esteem and self-worth; low self-control; suicidal ideation; poor physical health (difficulty sleeping, recurrent abdominal pain and frequent headaches); increased likelihood of self-injury; and loneliness. Furthermore, victims of cyberbullying are much more likely to be bullied in person when compared to non-victims.[37]

Additionally, both youth who experience cyberbullying victimization and perpetration are more likely to experience poor performance at school and in the workplace as compared to youth who are not involved in cyberbullying. They reported absenteeism, lower grades and poor concentration. Victims are also more likely to face detentions and suspensions, incidences of truancy, and carrying weapons.[38]

Ruangnapakul et al., in 2019, conducted a systematic review of studies from South Asian countries, i.e. Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, and the Philippines. The review revealed that cyberbullying behavior (perpetration or victimization) is common among adolescents in these countries. One of the studies from Philippines noted the association of cyberbullying with unpleasant and uncomfortable feelings. Another study from Malaysia reported that cyberbullying was associated with negative academic and emotional outcomes. The review revealed that there were few (not many) studies on cyberbullying in the Southeast Asian region. The issue needs further systematic enquiry. Since most of the studies were cross-sectional, they mainly report associations and not temporality (e.g., which came first- poor adjustment and functioning, or cyberbullying?) which would require longitudinal studies.[39]

Bullying among youth is costly not just for individuals and families but also for countries. Understanding the economic cost and impacts associated with bullying is critical for any country. Such data informs the design of appropriate evidence-informed programs and prevention measures to reduce its occurrence. To move in this direction, India needs to conduct surveys and ensure availability of administrative data with trends to allow estimates of bullying prevalence and consequences.[40]

Reports from elsewhere suggest alarming costs. For instance, youth violence in Brazil alone is estimated to cost nearly $19 billion per year, of which $943 million can be linked to violence in schools. A report commissioned by Australia’s Alannah and Madeline Foundation suggests the costs of bullying victims and perpetrators into adulthood is $1.8 billion over a 20 years period. This includes the costs of bullying for all school students during school as well as long-term impacts after school.[41]

Cyberbullying is a global problem that affects youth’s mental, socio-economic, psychological, and physical health. This requires a multi-disciplinary, cross-cultural and holistic approach to address the issue through programs focused on students and school personnel, parents, health professionals and the wider community. The more extensive ecological system comprising parents, teachers, various stakeholders like media, law enforcement, health professionals, policymakers, and youth themselves all need to work in active collaboration to deal with the problem of cyberbullying. In this context, the social-ecological model proposed by the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for violence prevention is useful and merits discussion.

A FRAMEWORK FOR PREVENTION

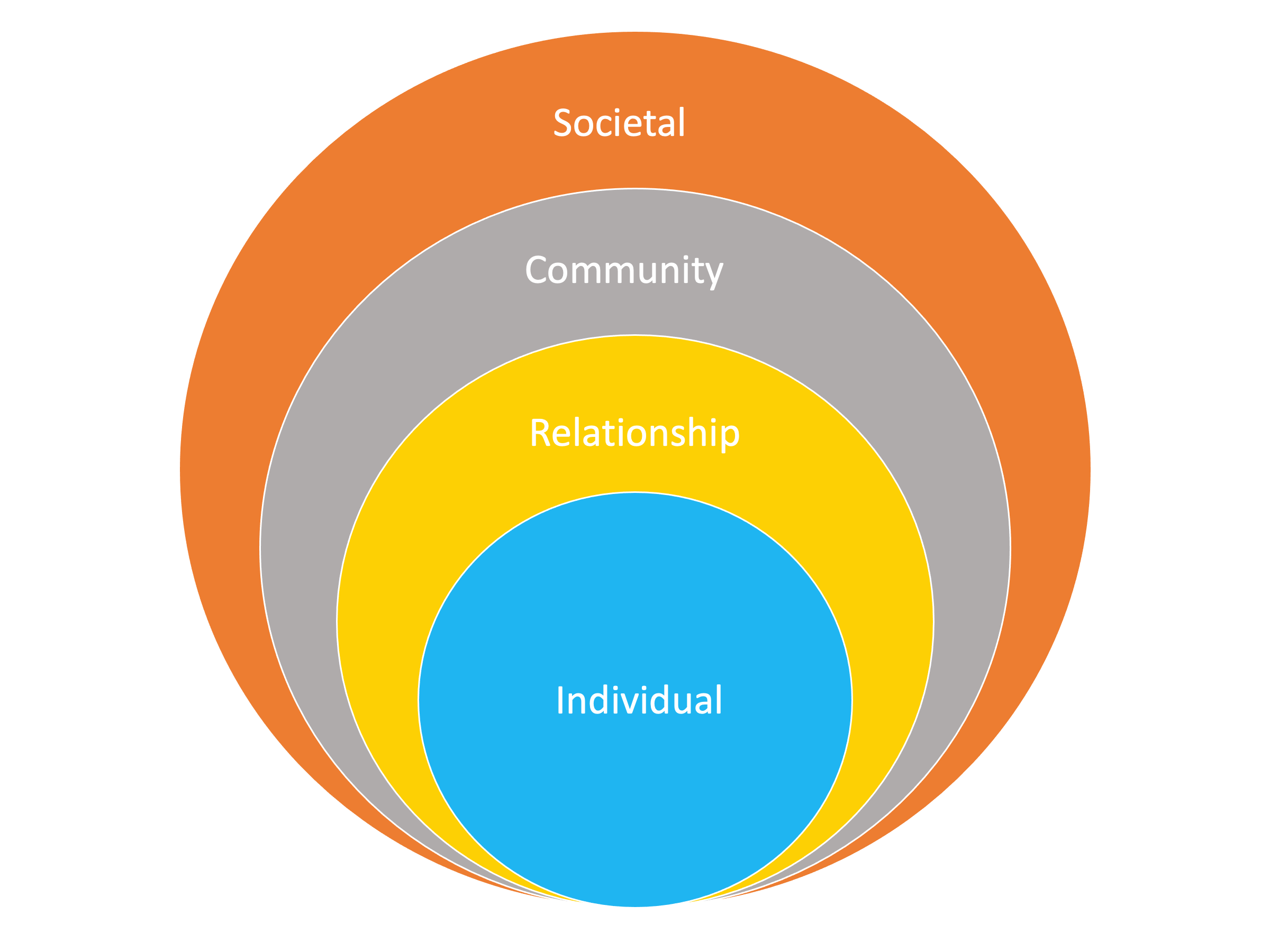

Through this book, we aim to empower stakeholders who perform an essential role in the dynamic play of factors that lead to cyberbullying. Knowing the range of actors and factors is critical to prevent and respond to the risk. We use a four-level social-ecological model proposed by CDC (Refer Figure 1) to understand violence and the effectiveness of potential prevention strategies. This model considers the complex interplay between individual, relationship, community, and societal levels leading to interpersonal-violence. It allows us to understand the determinants at each level that put individuals at risk for violence or protect them from experiencing the violence.

The model also explains how the factors at one level influence factors at another level, which requires action across multiple levels of the model at the same time to achieve population-level impact.[42],[43] Throughout the book, we utilize the socio-ecological framework to understand cyberbullying among youth.

The model is understood through four concentric circles. The innermost circle is the one closest to the individual and the outermost circle is the most distant, yet influential at the societal level. The individual level identifies biological, individual characteristics and personal history factors. These factors often increase the probability of becoming a victim or perpetrator of violence. Some of these factors include age, education, family income, impulsivity, or history of adversity such as abuse.

The next level moves out of the individual and examines close relationships. Some close relationships may increase the risk of experiencing cyberbullying as a victim or perpetrator of cyberbullying. For instance, an individual’s family members influence their behavior and contribute to their risk of or protection against cyberbullying. Also, peers play a critical role in influencing children’s behavior, attitude, thinking and judgment.

This model at third level, the community level, explores settings, such as schools, workplaces, and neighborhoods. In some settings in which social relationships develop may contribute towards factors that are associated with victimization or perpetration of cyberbullying.

The fourth level looks at the broad societal factors that help create an environment in which violence is either encouraged or discouraged. These factors include political, social and cultural norms of the society in which we live. They also include various factors that help to maintain economic or social inequalities among different groups of the society.

In the following chapters, we have elaborated upon risk and protective factors of cyberbullying using the socio-ecological framework described above. The framework also helps understand the preventive strategies with a systems lens. We use insights gained from review of scientific and grey literature, policy documents and discussions held with youth, teachers, parents, health care providers and policy actors during workshops.

Chapter Two emphasizes the importance of a solid understanding of how best to measure cyberbullying within and across cultural contexts. We review the existing measures of cyberbullying in South Asia and provide guidance on measure development for researchers to generate ecologically valid measures of cyberbullying.

Chapter Three covers individual level determinants, relationships with peers and their effect on cyberbullying behavior. This chapter also conveys the role of school as a community level organization in preventing cyberbullying. Understanding school-and peer-level factors is important in preventing cyberbullying events and mitigating its potentially harmful impacts. By far these are the most studied factors addressed in interventions to prevent cyberbullying.

Chapter Four addresses parents’ and caregivers’ needs for guidance and reassurance on how best maintain their children’s safety online and protect against cyberbullying. We emphasize the importance of parent-child communication, warm parent-child relationships, and parental monitoring that supports adolescents’ search for autonomy. In short, this chapter details the role of family, especially parental relationships and media parenting with respect to cyberbullying behavior among youth.

Chapter Five focuses on the broader research areas of digital risks and online safety. We discuss

the three primary types of risks that adolescents navigate in digitally mediated environments that

extend beyond cyberbullying – online sexual solicitations and risk behaviors, exposure to explicit

content, and information breaches and privacy violations. We advocate for a resilience-based, rather than an abstinence-only approach to online safety. Once again, this chapter focuses on the

first two levels of the socio-ecological model; individual and relationship level.

Chapter Six addresses the more distal societal level factors identified by the model. We summarize

how the current knowledge can be applied in India across multiple stakeholder groups, including public policy, law enforcement, school administration, health care providers, community-based organizations, tech industry, and research institutes. Also, we highlight the key gaps in knowledge

to guide future research.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Increasing digital access enables education, socialization and entertainment among youth thus offering the most marginalized an opportunity to come out of poverty.

- Though digital access has improved worldwide, there remains inequality in access, particularly for children, especially girls from low-income families in the rural areas.

- Children all around the world are adapting these technologies at earlier ages and are far more adept than their parents in using them.

- Online risks are a reality of current connected work. Children, specifically, are exposed to the risk of cyberbullying, online harassment, sexual solicitation and risky sexual behaviors, exposure to explicit content, information breaches and privacy violations.

- According to existing literature, cyberbullying rates reported among youth in India range from 5% to 53% based on different studies. This is similar to rates reported elsewhere in developing settings and worldwide.

- The cyberbullying studies undertaken in India have methodological weaknesses such as unavailability of data pertaining to sub-groups. More information at the national level is required to inform policies and action on response.

- Cyberbullying and cyber victimization are both associated with a range of poor outcomes, including depressive symptoms, low self-esteem, anxiety, loneliness, drug and alcohol use, low academic achievement, and low overall well-being. In addition, cyber victimization has been linked to somatic complaints, perceived stress, and suicide ideation. However, most of this research is cross-sectional, and longitudinal studies are recommended to identify the direction of relationship of these effects.

- Nevertheless, the evidence of negative impacts of cyberbullying is sufficient to catalyze the policy ecosystem in India to prioritize digital safety and to strengthen systems to monitor, respond and prevent digital risks.

- Population Enumeration Data: Census of India. Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner, India; Ministry of Home Affairs, GOI. [Internet]. [cited 2021 Aug 23]. Available from: https://censusindia.gov.in/2011census/population_enumeration.html ↵

- Adolescent development and participation; UNICEF India. [Internet]. [cited 2021 Aug 23]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/india/what-we-do/adolescent-development-participation ↵

- Human resources for Health-WHO, World Health Organization. [Internet]. [cited 2021 Aug 23]. Available from: https://www.who.int/hrh/documents/JLi_hrh_report.pdf ↵

- Human resources for Health-WHO, World Health Organization. [Internet]. [cited 2021 Aug 23]. Available from: https://www.who.int/hrh/documents/JLi_hrh_report.pdf ↵

- Digital in India-IAMAI CMS. [Internet]. [cited 2021 Aug 23]. Previously available from: https://cms.iamai.in/Content/ResearchPapers/d3654bcc-002f-4fc7-ab39-e1fbeb00005d.pdf and now available from: https://www.iamai.in/KnowledgeCentre ↵

- By 2025, rural India will likely have more internet users than urban India. [Internet]. [cited 2021 Aug 23]. Available from: https://theprint.in/tech/by-2025-rural-india-will-likely-have-more-internet-users-than-urban-india/671024/ ↵

- Children in a Digital World: UNICEF. [Internet]. [cited 2021 Aug 23]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/media/48601/file ↵

- Swist T, Collin P, McCormack J, Third A. Social media and the wellbeing of children and young people: A literature review. ↵

- United Nations Children’s Fund and Move, ‘Igarité: Overview of face-to-face teaching with technological mediation in the state of Amazonas’, UNICEF Brazil, 2017. ↵

- Inoue K, Di Gropello E, Taylor YS, Gresham J. Out-of-school youth in Sub-Saharan Africa: A policy perspective. World Bank Publications; 2015 Mar 17. ↵

- Dhawan S. Online learning: A panacea in the time of COVID-19 crisis. Journal of Educational Technology Systems. 2020 Sep;49(1):5-22. ↵

- Sanou B. ICT facts and figures 2016. Geneva: The International Telecommunication Union (ITU). 2017 Mar. ↵

- GSM Association, ‘Bridging the Gender Gap: Mobile access and usage in low and middle-income countries’, GSMA, London, 2015, pp. 6–9, 29. ↵

- NFHS-5: National Family Health Survey: India. 2019-20. [Internet]. [cited 2021 Aug 23]. Available from: https://ruralindiaonline.org/en/library/resource/national-family-health-survey-nfhs-5-2019-20-fact-sheets-key-indicators—22-statesuts-from-phase-i/ ↵

- Children in a Digital World: UNICEF. [Internet]. [cited 2021 Aug 23]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/media/48601/file ↵

- Children in a Digital World: UNICEF. [Internet]. [cited 2021 Aug 23]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/media/48601/file ↵

- Children in a Digital World: UNICEF. [Internet]. [cited 2021 Aug 23]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/media/48601/file ↵

- An insider’s view of the games industry and what it offers children’s play. [Internet]. [cited 2021 Sep 25]. Available from: https://digitalfuturescommission.org.uk/blog/an-insiders-view-of-the-games-industry-and-what-it-offers-childrens-play/ ↵

- Solberg ME, Olweus D. Prevalence estimation of school bullying with the Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire. Aggressive Behavior: Official Journal of the International Society for Research on Aggression. 2003 Jun;29(3):239-68. ↵

- Hertz MF, David-Ferdon C. Electronic media and youth violence: A CDC issue brief for educators and caregivers. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control; 2008. ↵

- Mehari KR, Farrell AD. Where does cyberbullying fit? A comparison of competing models of adolescent aggression. Psychology of violence. 2018 Jan;8(1):31. ↵

- Prevention, protection and international cooperation against the use of new information technologies to abuse and/or exploit children. Commission on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice. Twenty-third session. Vienna, 12-16 May 2014. Available from: https://undocs.org/E/CN.15/2014/7 ↵

- Thakkar N, van Geel M, Vedder P. A systematic review of bullying and victimization among adolescents in India. International Journal of Bullying Prevention. 2020 Sep 7:1-7. ↵

- Child online protection in India; UNICEF. Available from: https://www.icmec.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/UNICEF-Child-Protection-Online-India-pub_doc115-1.pdf ↵

- Kowalski RM, Giumetti GW, Schroeder AN, Lattanner MR. Bullying in the digital age: A critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychological bulletin. 2014 Jul;140(4):1073. ↵

- Background paper on protecting children from bullying and cyberbullying. Expert Consultation on protecting children from bullying and cyberbullying. May 2016. Florence, Italy. Office of the special representative of the secretary-general on Violence against Children. [Internet]. [cited 2021 Aug 23]. Available from: https://violenceagainstchildren.un.org/sites/violenceagainstchildren.un.org/files/expert_consultations/bullying_and_cyberbullying/background_paper_expert_consultation_9-10_may.pdf ↵

- McHugh BC, Wisniewski PJ, Rosson MB, Xu H, Carroll JM. Most teens bounce back: Using diary methods to examine how quickly teens recover from episodic online risk exposure. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction. 2017 Dec 6;1(CSCW):1-9. ↵

- Table 9A.1-Cyber Crimes (State/UT-wise) – 2016-2018. Crime in India Table Contents. National Crime Records Bureau of India [Internet]. [cited 2021 Oct 18]. Available from: https://ncrb.gov.in/en/crime-in-india-table-addtional-table-and-chapter-contents?field_date_value%5Bvalue%5D%5Byear%5D=2018&field_select_table_title_of_crim_value=20&items_per_page=10 ↵

- Table 9A.1-Cyber Crimes (State/UT-wise) – 2018-2020. National Crime Records Bureau of India [Internet]. [cited 2021 Oct 18]. Available from: https://ncrb.gov.in/en/crime-in-india-table-addtional-table-and-chapter-contents?field_date_value%5Bvalue%5D%5Byear%5D=2020&field_select_table_title_of_crim_value=20&items_per_page=10 ↵

- McHugh BC, Wisniewski PJ, Rosson MB, Xu H, Carroll JM. Most teens bounce back: Using diary methods to examine how quickly teens recover from episodic online risk exposure. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction. 2017 Dec 6;1(CSCW):1-9. ↵

- Wiśniewski P, Xu H, Rosson MB, Carroll JM. Parents just don’t understand: Why teens don’t talk to parents about their online risk experiences. InProceedings of the 2017 ACM conference on computer supported cooperative work and social computing 2017 Feb 25 (pp. 523-540). ↵

- Background paper on protecting children from bullying and cyberbullying. Expert Consultation on protecting children from bullying and cyberbullying. May 2016. Florence, Italy. Office of the special representative of the secretary-general on Violence against Children. [Internet]. [cited 2021 Aug 23]. Available from: https://violenceagainstchildren.un.org/sites/violenceagainstchildren.un.org/files/expert_consultations/bullying_and_cyberbullying/background_paper_expert_consultation_9-10_may.pdf ↵

- Sharma D, Kishore J, Sharma N, Duggal M. Aggression in schools: cyberbullying and gender issues. Asian journal of psychiatry. 2017 Oct 1;29:142-5. ↵

- Bhat CB, Chang Shih-Hua, Ragan MA. Cyberbullying in Asia. Cyber Asia and the New Media. 2013;18; 36-39. ↵

- Online Safety and Internet Addiction. CRY [Internet]. [cited 2021 Jun 8]. Available from: https://www.cry.org/downloads/safety-and-protection/Online-Safety-and-Internet-Addiction-p.pdf ↵

- Cyberbullying in New Zealand. 8 October 2018. [Internet]. [cited 2021 Aug 23]. Available from: https://www.netsafe.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Cyberbullying-in-New-Zealand-Societal-Cost.pdf ↵

- Kowalski RM, Giumetti GW, Schroeder AN, Lattanner MR. Bullying in the digital age: A critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychological bulletin. 2014 Jul;140(4):1073. ↵

- Kowalski RM, Giumetti GW, Schroeder AN, Lattanner MR. Bullying in the digital age: A critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychological bulletin. 2014 Jul;140(4):1073. ↵

- Ruangnapakul N, Salam YD, Shawkat AR. A systematic analysis of cyber bullying in Southeast Asia countries. International Journal of Innovative Technology and Exploring Engineering. 2019;8(8S):104-11. ↵

- Crime, Violence and Economic Development in Brazil: Elements for Effective Public Policy. Report No. 36525. June 2006. [Internet]. [cited 2021 Aug 23]. Available from: https://pdba.georgetown.edu/Security/citizensecurity/brazil/documents/docworldbank.pdf ↵

- The economic cost of bullying in Australian schools. Alannah and Madeline Foundation. March 2018. [Internet]. [cited 2021 Aug 23]. Available from: https://www.amf.org.au/media/2505/amf-report-280218-final.pdf ↵

- The Social-Ecological Model: A Framework for Prevention – Violence Prevention, CDC [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 Jun 8]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/about/social-ecologicalmodel.html ↵

- Espelage DL, Polanin JR, Low SK. Teacher and staff perceptions of school environment as predictors of student aggression, victimization, and willingness to intervene in bullying situations. School psychology quarterly. 2014 Sep;29(3):287. ↵