Chapter 4: Parenting in the Digital Age: Best Practices to Prevent and Reduce Cyberbullying

Jennifer Doty and Karla J. Girón

ABSTRACT

Parents often feel overwhelmed when their children skillfully navigate technology and online environments that they are inexperienced with. As such, parents are heavily in need of guidance and reassurance on how to best maintain their children’s safety online and prevent cyberbullying. However, some differences in parenting across Western and Eastern cultures may influence approaches to media parenting. Further, given the novel nature of this research area and the fast-paced evolution of technology, longitudinal research on parenting and cyberbullying is lacking. Extensive research on effective interventions and media parenting strategies across diverse contexts are much needed.

This chapter examines the available literature on the importance of parents to protect their children against cyberbullying. This includes parent-child relationships, parent-child communication, and parental monitoring that supports adolescents’ search for autonomy. We conclude this chapter with several models, strategies, and resources for parents in their attempts to navigate the world of technology and prevent cyberbullying.

A substantial body of evidence has established the protective power of a supportive parent-child relationships to strengthen pro-social behaviors and reduce adolescent risk behaviors. Across Western and Eastern cultures, parent supportiveness and communication are associated with academic success, empathy, and pro-social behaviors.[1],[2],[3],[4] Parental monitoring reduces youth substance use, delinquent behaviors, sexual risk behaviors, and bullying in all its forms.[5],[6] However, parents report feeling overwhelmed by technology when it comes to online risks. Unsure of how to successfully monitor online behavior,[7] many parents worry about the effects of cyberbullying on their children. Parents are a critical protective factor for reducing cyberbullying risk at the relational level of the ecological system.

Supportive parent-child relationships protect against cyberbullying and enhance resilience of children who encounter high-risk environments. In a review of the literature, Elsaesser and colleagues found that most studies of parenting and cyberbullying suggested that parent-child relationships were negatively related to cyberbullying perpetration and victimization.[8] Parental monitoring may be less salient than warmth and connectedness.[9] Other research has found mixed results regarding parental monitoring in online contexts, suggesting that restrictive monitoring may not be the most effective.[10],[11] This hypothesis needs further examination, particularly in Eastern cultures. Notably, the majority of these studies were cross-sectional, which underscores the emerging nature of this research.

Because 70% of cyberbullying occurs at home and parents have expressed a need for digital safety information,[12] clear guidance and preventative programming is needed for parents. We know from research across several countries that cyberbullying prevention programs are effective.[13],[14],[15] A large majority of these programs have been implemented in schools and few have included parent support in their programming. Additionally, the majority of cyberbullying preventative interventions have been in European countries, with only a few scattered studies in the US, Middle East, and Australia.[16] In this chapter, we present the current knowledge of parenting strategies that are associated with low cyberbullying, highlighting available longitudinal research. We also emphasize the ways that online contexts may be similar and different to parenting in face-to-face contexts.

PARENT-CHILD CONNECTEDNESS AND FIRMNESS AS PROTECTION AGAINST CYBERBULLYING

Warm and caring relationships between parents and children balanced with rules and monitoring directly protect against cyberbullying victimization and perpetration. It may buffer against the negative outcomes of cyberbullying, promoting resilience.[17] Based on these characteristics, four parenting styles have been identified: 1. authoritative parenting characterized by warm and supportive yet firm parenting (e.g., listening to children’s perspectives while being consistent with rules); 2. authoritarian parenting characterized by controlling parenting (e.g., being rule and punishment focused); 3. permissive parenting characterized by warmth and support with little support for rules; 4. neglectful parenting characterized by low warmth and low control. Authoritative parenting has repeatedly been shown to have the best outcomes for youth.

With respect to cyberbullying, youth entering secondary school in the Netherlands who reported having authoritarian parents had the lowest levels of cyberbullying victimization and perpetration.[18] Their parents were both warm and set firm rules. However, few longitudinal studies have examined cyberbullying and parenting. In a notable exception of 488 youth in the northwest of the U.S., researchers examined parenting styles, including authoritative parenting and authoritarian parenting.[19] They found that warm and supportive aspects of parenting at age 12 were related to cyberbullying perpetration at age 19. Authoritarian parenting, though, was related to increased risk of cyberbullying perpetration. Similarly, a larger Cyprus study examining the longitudinal effects of parenting on cyberbullying and victimization found that parenting predicted face-to-face and cyber bullying and victimization. Authoritarian parenting had a positive effect on aggression.[20]

Other studies have noted that youth who reported parental warmth had reduced exposure to cyberbullying and were less likely to experience the negative effects of cyberbullying when it did occur. Accordino & Accordino noted that students with closer parental relationships experienced less bullying.[21] Further, in a national U.S. sample, parental support (e.g., helping and comforting) was linked to lower risk of cyberbullying victimization and perpetration.[22] Another study found that cyberbullying and depression were more likely in adolescents with perceptions of low parental attachment compared to adolescents with more restrictive parents.[23]

THE IMPORTANCE OF PARENT-ADOLESCENT COMMUNICATION

Communication between parents and adolescents also has been identified as a protective factor against cyberbullying. In a study of high school students in Valencia, Spain, open communication with mother and father was more prevalent among students who had not been cyberbullied. Avoidant communication was more likely among students who had experienced cyberbullying either occasionally or severely.[24] Similarly, parent-child connectedness, as measured by open communication, was negatively related to cyberbullying victimization and perpetration above and beyond the effects of parents’ online monitoring.[25] This suggests that a strong relationship featuring open communication may be more important than monitoring youth behaviors online.

The importance of communication to prevent cyberbullying and protect against its negative outcomes was reinforced in qualitative interviews with parents. For example, in the south of the U.S., parents were intentional about teaching their children to take a different perspective when cyberbullying occurred. An example of one such conversation was, “[I’ll ask,] ‘Why do you think someone else would do that? They must be sad.’ Like, [I’ll] talk about these people when they’re bullying, ‘They have an issue. If they don’t like you, it’s an issue in them, not in you. It’s not something you did’.[26] They also wanted their children to understand the potential reasons why someone might cyberbully (e.g., poor home life; low self-esteem). Parents also employed communication strategies to empower their children. They taught their children to stand up to bullies to protect others who were vulnerable. They also worked to instill a sense of self-confidence in their own abilities. One parent said, “[My daughter] had an innate talent for music, so we signed her up for piano classes and enrolled her in the school orchestra. She got chosen to represent and sit in the front row and that was a big deal. Beyond that, her grades went up, and she was focusing on her studies, so then we would remind her of that. [We would say,] ‘These other kids may be bigger than you …, but you can make music like they cannot’”.[27] These parents took a preventative stance against cyberbullying. Given the focus on collective interdependence in India and other Eastern cultures,[28] qualitative research is needed to understand how parents’ strategies may differ from parents in Western cultures.

Other research has found that when students did experience cyberbullying, talking to parents was a helpful coping strategy.[29] However, in a mixed methods study of parents and children (6th – 9th grade) in England, Cassidy et al. reported a discrepancy in youth report of cyberbullying (32% victimization; 36% perpetration) and parent knowledge of cyberbullying (11% were aware of cyberbullying incidents).[30] These findings indicate that youth do not always communicate experiences of online harassment with their parents. This is similar to findings in Barlett and Fennel,[31] where parents believed their enforcement of rules to be greater, and their child’s cyberbullying behaviors to be lower, than the youth actually reported. In a second study, the researchers also found that cyberbullying behaviors were positively associated with, and predicted by, the extent to which parents were unaware of their children’s internet use (see also Chapter 5 on online safety). It may be that youth do not seek adult support because they don’t believe that adults will be able to successfully intervene, or they fear losing access to their devices. However, without adult help youth are more likely to engage in maladaptive coping such as avoidance, becoming cyberbullying perpetrators themselves, or physical retaliation against the perpetrator(s). All of these may allow an increase in cyberbullying.[32]

WHY AUTONOMY SUPPORTIVE PARENTING IS IMPORTANT

Experts advocate a mix of parenting strategies to curb cyberbullying and increase online safety. A strong emphasis on active media monitoring and autonomy may be the most effective parenting approach.[33] Media parenting refers to “goal-directed parent behaviors or interactions with their child about media for the purpose of influencing some aspect of the youth’s screen media use behaviors.”[34] Parents and youth naturally negotiate boundaries—including limits for online activities—over the course of adolescence as young people strive to become more independent and parents strive to keep them safe.[35] Parents and youth demonstrate a range of patterns in these negotiations, but families where parents exert high control and youth push for high autonomy are likely to have the most conflict.[36]

One study found that when youth reported high parental control, they also were likely to report high levels of cyberbullying.[37] In contrast, Ghosh and colleagues found that parents who were involved and autonomy granting, who strictly supervised adolescents online had adolescents who were likely to report low cyberbullying victimization.[38] In other words, a balanced approach may be the best. Similarly, in a study of adolescents, Padilla-Walker et al. found that autonomy supportive media parenting (whether active or restrictive) was associated with high media disclosure.[39] The study also found that when children voluntarily tell their parents about their online activities, they tend to engage in more pro-social activities and less relational aggression.

HOW CAN PARENTS INFLUENCE ADOLESCENTS TO REDUCE CYBERBULLYING?

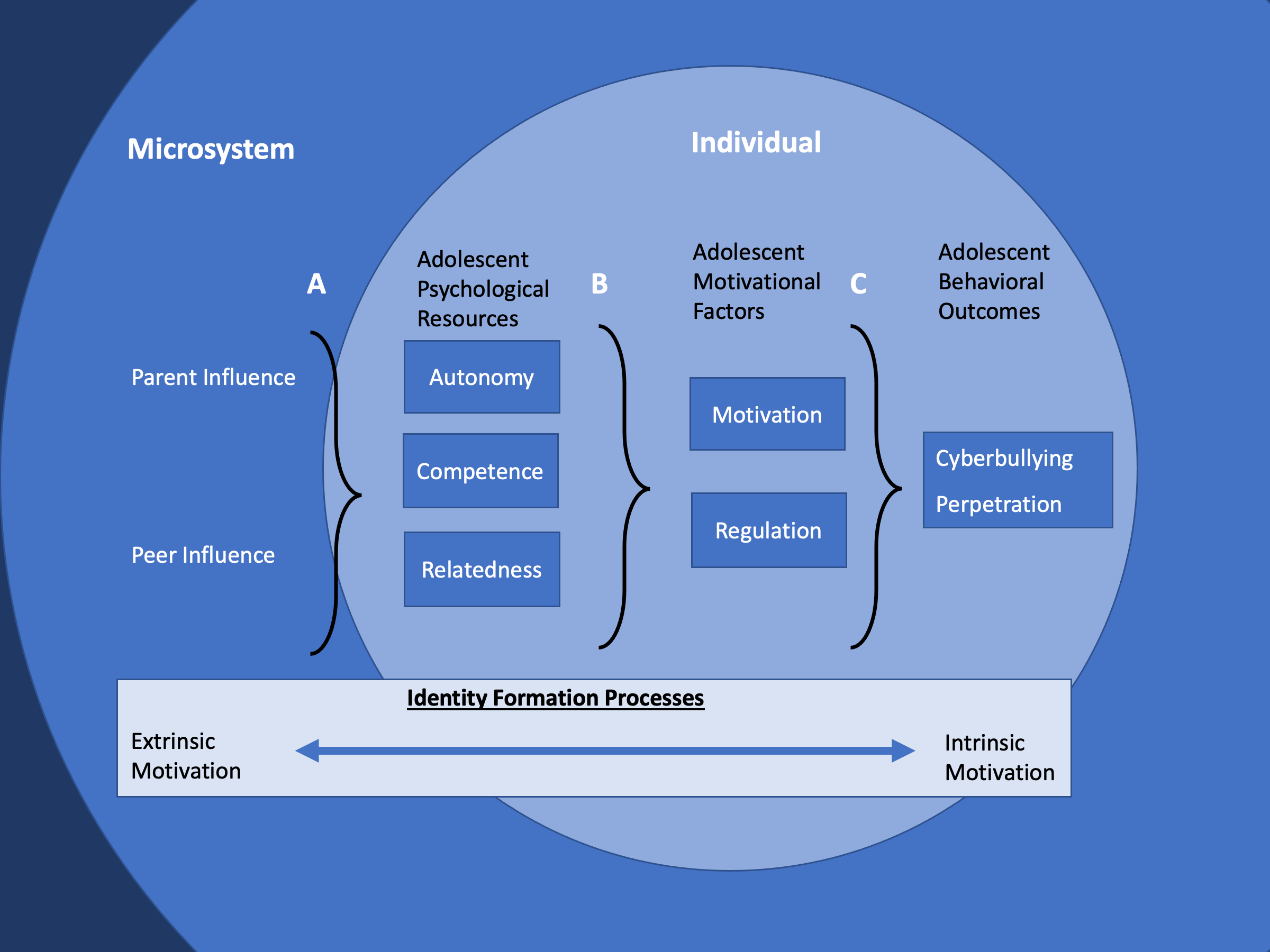

Why do adolescents cyberbully? What can parents do to curb cyberbullying perpetration? The Model for Cyberbullying Motivation and Regulation (MCMR) addresses these questions (see Figure 5 and 6).[40]

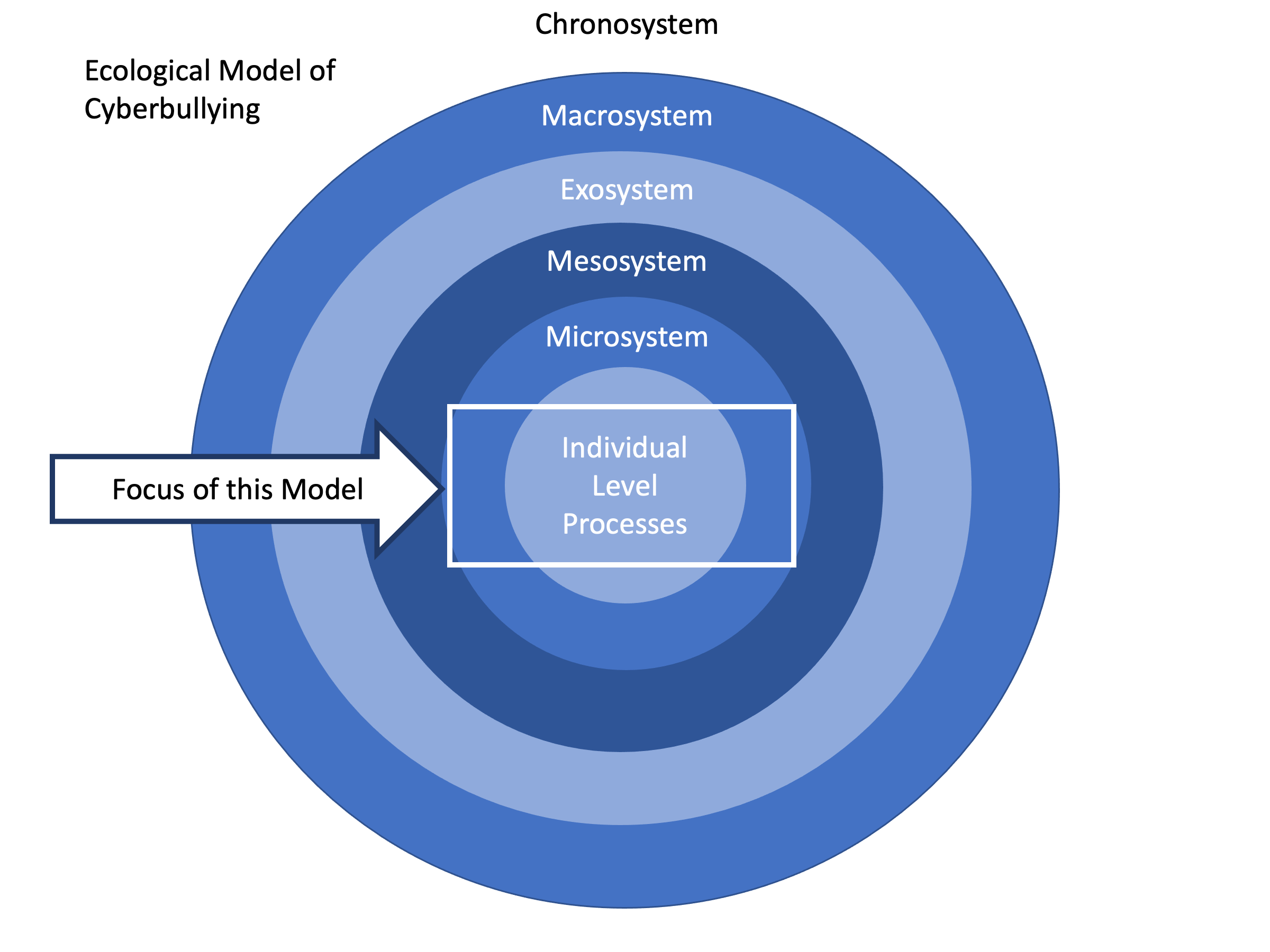

MCMR is grounded in an ecological perspective and focuses on the core processes that lead to cyberbullying perpetration by applying concepts from Self-Determination Theory.[41] While other theories focus on individual reasons for cyberbullying (e.g., anonymity, strain),[42] this theory focuses on the social influence on individuals. Large scale influences are known as the social level of the ecological system, for example government regulation of media. Local influences like schools and community policies are community level influences. Small scale influences, like individuals who have daily contact with a child, are known as the relational level of influence (when those individuals interact with each other, it is considered the interactional level). Specifically, parenting and peers are key influences in adolescents’ daily lives, which influence important psychological processes: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. These psychological processes influence adolescents’ motivation and self-regulation when it comes to cyberbullying.

RESTRICTIVE AND ACTIVE MEDIA PARENTING

Studies targeting cyberbullying outcomes have further identified possible protective effects for media parenting behaviors, such as parental monitoring of online behavior.[43],[44] Restrictive parenting practices include placing limits on media, whether through house rules or technology controls. The Pew institute found that the majority of parents monitor their adolescents on social media (up to 61%), and many review their texts or calls (48%).[45] Active mediation refers to parent-child discussions of media use and the active use of media together, known as co-use.[46] Compared to restrictive media parenting, parents are less likely to actively educate or discuss online behavior with their adolescents (40%).

Restrictive media monitoring has mixed results in the literature with respect to cyberbullying outcomes. For example, in one cross-sectional study, parents’ restriction of technology and discussion of online safety was associated with more cyberbullying perpetration.[47] This may be because when parents are aware of cyberbullying they may increase limits. In a longitudinal study, restrictive media monitoring was less effective than parent-child discussion and connective co-use (e.g., active use of media together). It may be that monitoring in face-to-face contexts requires open communication (e.g., “Where are you going tonight? Who will you be with?) while online monitoring may be achieved without communication (e.g., Watching TikTok videos or following Instagram without commenting). Indeed, some adolescents have expressed resentment when their father followed them or their friends on social media.[48]

The key to restrictive parenting practices may be to simultaneously support autonomy, a key construct in the Model for Cyberbullying Motivation and Regulation. Active discussion and negotiation around media, especially as children get older, would allow them to grow and learn.[49] Active media parenting has been shown to promote sympathy and self-regulation, which in turn was related to lower aggression and externalizing behavior and higher pro-social behavior.[50] Overall, warm parent-child relationships, communication and active media parenting are critical to combine with some practical restrictions, such as parental controls on phones for early adolescents. However, too much emphasis on control and restriction can backfire.

NEED FOR BUILDING YOUTH SOCIAL COMPETENCE ONLINE

Parents report being overwhelmed with technology. Many feel that they cannot keep up with adolescents’ abilities to navigate the digital world.[51] Dyadic research, with both parents and children, confirms that youth are often exposed to much more than their parents realize.[52],[53] Access to technology may have encouraged youth to hold a greater sense of autonomy that adolescents had in the past. Many parents express a sense of losing control.[54] However, despite youth competence online, and parents’ lack of confidence, parents’ role in educating youth about online risks remains critical.[55]

Despite technology skills, youth frequently lack the social experience to healthfully navigate the online world on their own. Past research on media parenting has demonstrated the importance of explaining the negative consequences of risky behavior to youth.[56],[57] Furthermore, while parents tend toward restriction as a solution,7 complete control is not a realistic choice in a media saturated environment. As children age they need to learn to navigate the online environment.[58] Wisniewski et al found that when youth were given opportunities to engage with others online, they were more likely to correct their own mistakes.[59] Further, parents themselves have emphasized the importance of teaching kindness and perspective taking in online settings.[60],[61] In one study of digital parenting in Indonesia, mothers reported basic competence in digital parenting and guiding children online, but they felt inadequate in the area of encouraging their children’s creativity and empowerment online.[62] Another important consideration is that parents may restrict girls more than boys in online spaces.[63],[64] This can negatively impact their technology skill development. Regardless of gender, parenting practices that allow appropriate learning as per age and maturity of the child, while educating them about online risks are likely to support both social competence and growth. This may be more challenging for parents who have a low digital literacy themselves, which is more common among low socio-economic status families.[65]

INVESTMENT IN STRONG PARENT-CHILD RELATIONSHIPS

One of the key take-aways of the literature on parenting and cyberbullying is that warm and loving parent-child relationships are foundational protective factors for youth. Ultimately, they are stronger deterrents of cyberbullying perpetration and victimization than restriction across cultures.[66],[67],[68] One tactic that parents may consider is leveraging technology to strengthen parent-child relationships. Vaterlaus et al. found that synchronous use of computer mediated communication was related to quality time for parents and their adolescents or young adults.[69] Evidence also suggests that active mediation may not only improve relationships, but potentially protect adolescents from the negative effects of cyberbullying. One study found that parents’ active mediation was associated with greater likelihood of talking to parents when cyberbullying occurred, particularly when there was a perception of harm.[70]

Time-tested strategies for improving parent-adolescent relationships are also recommended. Focusing on positive parenting builds a foundation for a strong parent-adolescent relationship.[71] This includes actively recognizing the positive behaviors of adolescents. Many times, parents tune into the behaviors that they want their children to change. They often forget to acknowledge the things their child is doing well. Additionally, spending quality time with adolescents is critical. In keeping with autonomy supportive parenting, letting an adolescent choose the activity may help improve their engagement in time spent together. Research has found that parental quality time is related to both parent and adolescent reports of happiness, meaning, decreases in stress.[72] Even small amounts of parental time have been found to improve child well-being.[73],[74] Given reports that technology may interfere with parent-child time together, being intentional about spending time together has gained importance.

MEDIA PARENTING

A critical theme in the literature is the importance of matching technology to what is developmentally appropriate for adolescents. In interviews with early adolescents, the teens themselves noted that maturity should be a factor in deciding when they should get smart phones.[75] They also noted that, at least for early adolescents, parents should have the final say on technology decisions. Experts in media parenting have suggested some basic guidelines for parents using the T.E.C.H. Parenting guidelines (see Table 2). First, they recommend being aware of what is appropriate for each age developmentally.[76] For example, most social media companies do not officially allow children under the age of 13 to have their own account. Kindness Wins is a resource for parents to teach their children appropriate and kind interactions as they begin to use technology.[77] Additionally, it is important to teach children the consequences of risk behavior that are rarely portrayed in the media.[78]

| TECH Parenting | Examples: |

|---|---|

| Talk about media use with children and monitor online activities | Ask what they are doing online in a non-judgmental way. (i.e., What are some of your favorite memes right now? How do you spend your time online?) |

| Educate children about the risks of media use | Explain inaccuracies in marketing and media depictions of risky behaviors, along with the relevant safe and normative practices (i.e., The characters in this show are smoking, but none of them are shown to have health consequences) |

| Actively co-use and co-watch media with children | Watch appropriate shows together and learn about their preferred sources of media (i.e., Can we watch your favorite shows together? This show has too much sexual content, we need to turn it off now) |

| Establish house rules for media use that are both clear and effective | Set boundaries around media platforms and levels of usage allowed (i.e., No HBO shows allowed; No iPad use in the bedroom after 6PM) |

Regarding co-use, experts recommend spending time together online. Parents may consider watching their child’s favorite streaming service together or playing with Snapchat filters together. Using technology together gives parents a chance to model healthy behaviors and self-restriction when something inappropriate comes up.[79] Co-use may also include learning about the media children and adolescents are using.[80] For example, parents can screen media content and apps on sites like CommonSenseMedia.org, which gives caregivers advice on what is appropriate by age.[81]

Finally, establishing clear house rules is crucial. Often parents report that they have rules, but the youth are less clear about those rules.[82] Rules that set boundaries for when, where, and how long a youth can be online are shown to reduce online risk taking.[83],[84] The American Academy of Pediatrics has set up a website to help families establish family rules about screen time that are realistic for each family’s situation and appropriate by age of child. The Family Media Plan can be found at https://www.healthychildren.org/English/media/Pages/default.aspx. Once they are set, keeping the rules posted in a spot where parents and youth can see them for reference is a recommended practice.[85] Parents may also consider tracking how often youth follow the rules and providing small rewards or acknowledgements of good behavior.[86] Although technology can be employed to help keep the house rules, transparency and communication about the rules is likely to be more important in the long run.

Another model provides guidelines specifically for families with adolescents. The TOSS for teens guidelines are specifically geared toward balancing media parenting with teens’ growing independence, with an eye toward encouraging teen responsibility and growth (See Chapter 5). Teen Online Safety Strategies is a conceptual framework with two main strategies for maintaining online safety, focusing attention on parents and their teens’ actions. TOSS emphasizes the importance of parental control through the use of monitoring, restriction, and active mediation. It also emphasizes the importance of teens’ self-regulation through their self-awareness, impulse control, and risk-coping.[87] These parent-child strategies are also meant to be analogous, where either can execute their corresponding strategies with the other’s help. A review of interventions for face-to-face bullying highlights the need to include parents in prevention efforts. Parent involvement was among the most effective components of such programs.[88]

APPLICATION TO INDIA

Western parents may emphasize independence in their approach to parenting, which may encourage online exploration. Parents in Eastern cultures, including India, tend to take a more collective approach focused on interdependence and protection.[89] Research on the relationship between parenting and cyberbullying in India is still in emerging phase. Recent studies in other Eastern countries suggest that authoritative parenting, which combines both warmth and firm limit setting, may also be a good strategy to apply in India. For example, in Korea, hours of technology use (specifically smartphone usage during weekdays and computer usage during weekends), and negative parenting such as coercive practices, rejection, and chaotic home management increased risk of cyberbullying perpetration for middle school students.[90] In another study, among girls, mother-daughter closeness and maternal monitoring predicted lower bullying and cyberbullying directly, and indirectly through self-control. However, paternal closeness predicted higher bullying. Father approval of peers predicted lower bullying and cyberbullying.[91]

Although parental autonomy support in India is increasing,[92] the effectiveness of autonomy support in media parenting is yet unknown. One study in Hong Kong found that inconsistency in autonomy support between parents was related to cyberbullying victimization.[93] When the father figure followed autonomy-supportive parenting while the mother figure had high levels of control, adolescents had greater victimization. Patterns of warm yet firm parenting may reduce cyberbullying but further research is needed to understand cultural nuances.

GAPS IN THE LITERATURE

The literature clearly points to the importance of strong parent-child relationships and the potential of media parenting to reduce cyberbullying and online aggression. However, longitudinal research is needed to understand the processes by which parents make a difference. For example, in a cross-sectional research, being cyberbullied was associated with greater parental monitoring.[94] Do parents react when a child is cyberbullied and then follow up with new rules to protect their child? We still do not know the answer to that question.

Further, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying interventions found that to-date, no parenting intervention has been developed and tested to reduce cyberbullying.[95] A recent randomized clinical trial inviting parents and adolescents to engage in the American Academy of Pediatrics Family Media Plan found no substantial change in media rule engagement among adolescents (e.g., talking with parents about rules, following rules).[96] The authors and commentators suggested that the educational delivery of media parenting be enhanced by youth engagement and integration of behavior change strategies to promote ongoing reinforcement of family media rules. These suggestions, however, need further investigation.

In the next chapter, we discuss the risks associated with cyberbullying. Chapter five focuses on the broader research areas of digital risks and online safety. We discuss the three primary types of risks that adolescents navigate in digitally mediated environments that extend beyond cyberbullying – online sexual solicitations and risk behaviors, exposure to explicit content, and information breaches, and privacy violations. We advocate for a resilience-based, rather than an abstinence-only approach to online safety. Once again, this chapter focuses on the first two levels of the socio-ecological model: individual and relationship levels.

CONCLUSION

This chapter provides an overview of ways that parents can contribute to the prevention of cyberbullying at the relational level of the ecological system. Overall, the prevailing literature reinforces the comment one parent made in a qualitative study: “It all starts at home. If children do not see kindness and respect from siblings, friends, and parents—the war is nearly lost. Music videos, Hollywood names, commercial T.V., magazines all contribute to a blitz of disrespect and an unreal sense of power. Power to do things and believe that you can get away with it, which in fact you do get away with it.”[97] The current research reinforces a number of practical ways parents can reduce cyberbullying risk, including support for adolescents’ autonomy, active media parenting that includes co-use of technology, and nurturing strong parent-child relationships. However, much of the research has been conducted in Europe and the U.S., and the need for understanding cultural differences remains.

KEY TAKE-AWAYS

- Restrictive monitoring of adolescents’ online activities does not deter cyberbullying perpetration and victimization to the same extent as creating warm and loving parent-child relationships or autonomy-supportive restriction.

- Although youth may not always be willing to share information with their parents, establishing effective communication channels between parents and children is important for preventing cyberbullying and its associated outcomes, as well as serving as a coping strategy for cyberbullied youth.

- Parents should discuss the consequences of risky online behavior, balance their children’s technology use with other activities, and ensure age-appropriate use of technology in order to develop youths’ social competence in the online world.

- Doty JL, Gower AL, Rudi JH, McMorris BJ, Borowsky IW. Patterns of bullying and sexual harassment: Connections with parents and teachers as direct protective factors. J Youth Adolesc 2017 4611. 2017;46(11):2289-2304. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0698-0 ↵

- Moitra T, Mukherjee I. Does parenting behaviour impacts delinquency? A comparative study of delinquents and non-delinquents. Int J Crim Justice Sci. 2010;5(2):274-285. Accessed October 2, 2021. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.676.4229&rep=rep1&type=pdf ↵

- Masud H, Thurasamy R, Ahmad MS. Parenting styles and academic achievement of young adolescents: A systematic literature review. Qual Quant 2014 496. 2014;49(6):2411-2433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-014-0120-x ↵

- Padilla-Walker LM, Christensen KJ. Empathy and self-regulation as mediators between parenting and adolescents’ prosocial behavior toward strangers, friends, and family. J Res Adolesc. 2011;21(3):545-551. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00695.x ↵

- Doty JL, Lynne SD, Metz AS, Yourell JL, Espelage DL. Bullying perpetration and perceived parental monitoring: A random intercepts cross-lagged panel model. Youth Soc. Published online July 8, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0044118X20938416 ↵

- Dishion TJ, Kim H, Tein J. Friendship and adolescent problem behavior: Deviancy training and coercive joining as dynamic mediators. In: Beauchaine TP, Hinshaw SP, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Externalizing Spectrum Disorders; 2015:303–311. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199324675.001.0001 ↵

- Helfrich EL, Doty JL, Su YW, Yourell JL, Gabrielli J. Parental views on preventing and minimizing negative effects of cyberbullying. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;118:105377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105377 ↵

- Elsaesser C, Russell B, Ohannessian CMC, Patton D. Parenting in a digital age: A review of parents’ role in preventing adolescent cyberbullying. Aggress Violent Behav. 2017;35:62-72. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AVB.2017.06.004 ↵

- Elsaesser C, Russell B, Ohannessian CMC, Patton D. Parenting in a digital age: A review of parents’ role in preventing adolescent cyberbullying. Aggress Violent Behav. 2017;35:62-72. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AVB.2017.06.004 ↵

- Meter DJ, Bauman S. Moral Disengagement About cyberbullying and parental monitoring: Effects on traditional bullying and victimization via cyberbullying involvement. J Early Adolesc. 2018;38(3):303-326. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431616670752 ↵

- Wisniewski P, Carroll JM, Rosson MB. Grand challenges of researching adolescent online safety: A family systems approach. In: Association for Information Systems Conference Proceedings; 2013. ↵

- Kowalski RM, Limber SP, Agatston PW. Cyberbullying: Bullying in the Digital Age. Wiley-Blackwell; 2012. ↵

- Doty JL, Girón K, Mehari RK, et al. The dosage, context, and modality of interventions to prevent cyberbullying perpetration and victimization: A systematic review. Prev Sci. In press. ↵

- Gaffney H, Farrington DP, Espelage DL, Ttofi MM. Are cyberbullying intervention and prevention programs effective? A systematic and meta-analytical review. Aggress Violent Behav. 2019;45:134-153. ↵

- Polanin JR, Espelage DL, Grotpeter JK, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of Interventions to decrease cyberbullying perpetration and victimization. Prev Sci 2021. 2021;1:1-16. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11121-021-01259-Y ↵

- Doty JL, Girón K, Mehari RK, et al. The dosage, context, and modality of interventions to prevent cyberbullying perpetration and victimization: A systematic review. Prev Sci. In press. ↵

- Elsaesser C, Russell B, Ohannessian CMC, Patton D. Parenting in a digital age: A review of parents’ role in preventing adolescent cyberbullying. Aggress Violent Behav. 2017;35:62-72. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AVB.2017.06.004 ↵

- Dehue F, Bolman C, Vollink T, Pouwelse M. Cyberbullying and traditional bullying in relation with adolescents perception of parenting. J Cyber Ther Rehabil. 2012;5:25-34. Accessed October 2, 2021. https://www.academia.edu/download/30333550/cyberbullying_and_traditional_bullying_in_relation_to_adolescents_perception_of_parenting.pdf#page=27 ↵

- Zurcher JD, Holmgren HG, Coyne SM, Barlett CP, Yang C. Parenting and cyberbullying across adolescence. Cyberpsychology, Behav Soc Netw. 2018;21(5):294-303. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2017.0586 ↵

- Charalampous K, Demetriou C, Tricha L, et al. The effect of parental style on bullying and cyber bullying behaviors and the mediating role of peer attachment relationships: A longitudinal study. J Adolesc. 2018;64:109-123. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ADOLESCENCE.2018.02.003 ↵

- Accordino DDB, Accordino MPM. An exploratory study of face-to-face and cyberbullying in sixth grade students. Am Second Educ. 2011;40(1):14-30. Accessed October 2, 2021. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23100411?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents ↵

- Wang J, Iannotti RJ, Nansel TR. School bullying among adolescents in the United States: physical, verbal, relational, and cyber. J Adolesc Heal. 2009;45(4):368-375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.021 ↵

- Chang FC, Chiu CH, Miao NF, et al. The relationship between parental mediation and Internet addiction among adolescents, and the association with cyberbullying and depression. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;57:21-28. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.COMPPSYCH.2014.11.013 ↵

- Ortega-Barón J, Buelga S, Ayllón E, Martínez-Ferrer B, Cava M-J. Effects of intervention Program Prev@cib on traditional bullying and cyberbullying. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(4):527. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16040527 ↵

- Doty J, Gower A, Sieving R, Plowman S, McMorris B. Cyberbullying victimization and perpetration, connectedness, and monitoring of online activities: Protection from parental figures. Soc Sci. 2018;7(12):265. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7120265 ↵

- Helfrich EL, Doty JL, Su YW, Yourell JL, Gabrielli J. Parental views on preventing and minimizing negative effects of cyberbullying. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;118:105377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105377 ↵

- Helfrich EL, Doty JL, Su YW, Yourell JL, Gabrielli J. Parental views on preventing and minimizing negative effects of cyberbullying. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;118:105377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105377 ↵

- Sondhi R. Parenting adolescents in India: A cultural perspective. In: Child and Adolescent Mental Health. InTech; 2017. https://doi.org/10.5772/66451 ↵

- Paul S, Smith PK, Blumberg HH. Revisiting cyberbullying in schools using the quality circle approach: http://dx.doi.org/101177/0143034312445243. 2012;33(5):492-504. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034312445243 ↵

- Cassidy W, Brown K, Jackson M. “Making kind cool”: Parents’ suggestions for preventing cyber bullying and fostering cyber kindness. J Educ Comput Res. 2012;46(4):415-436. ↵

- Barlett CP, Fennel M. Examining the relation between parental ignorance and youths’ cyberbullying perpetration. Psychol Pop Media Cult. 2018;7(4):547-560. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000139 ↵

- Hoff DL, Mitchell SN. Cyberbullying: causes, effects, and remedies. J Educ Adm. 2009;47(5):652-665. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578230910981107 ↵

- Jackson KM, Janssen T, Gabrielli J. Media/marketing influences on adolescent and young adult substance abuse. Curr Addict Reports 2018 52. 2018;5(2):146-157. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40429-018-0199-6 ↵

- O’Connor TM, Hingle M, Chuang R-J, et al. Conceptual understanding of screen media parenting: report of a working group. https://home.liebertpub.com/chi. 2013;9(SUPPL.1). https://doi.org/10.1089/CHI.2013.0025 ↵

- Erickson LB, Wisniewski P, Xu H, Carroll JM, Rosson MB, Perkins DF. The boundaries between: Parental involvement in a teen’s online world. J Assoc Inf Sci Technol. 2016;67(6):1384-1403. https://doi.org/10.1002/ASI.23450 ↵

- Erickson LB, Wisniewski P, Xu H, Carroll JM, Rosson MB, Perkins DF. The boundaries between: Parental involvement in a teen’s online world. J Assoc Inf Sci Technol. 2016;67(6):1384-1403. https://doi.org/10.1002/ASI.23450 ↵

- Fousiani K, Dimitropoulou P, Michaelides MP, Van Petegem S. Perceived parenting and adolescent cyber-bullying: Examining the intervening role of autonomy and relatedness need satisfaction, empathic concern and recognition of humanness. J Child Fam Stud 2016 257. 2016;25(7):2120-2129. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10826-016-0401-1 ↵

- Ghosh AK, Wisniewski P, Badillo-Urquiola K. Examining the effects of parenting styles on offline and online adolescent peer problems. Proc Int ACM Siggr Conf Support Gr Work. Published online January 7, 2018:150-153. https://doi.org/10.1145/3148330.3154519 ↵

- Padilla-Walker LM, Stockdale LA, Son D, Coyne SM, Stinnett SC. Associations between parental media monitoring style, information management, and prosocial and aggressive behaviors. J Soc Pers Relat. 2020;37(1):180-200. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407519859653 ↵

- Doty JL, Barlett CP, Gabriellic J, Yourell JL, Su Y-W, Waasdorpe TE. A theory of cyberbullying perpetration among adolescents: examining proximal processes. Under Review. ↵

- Ryan RM. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55(1):68. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68 ↵

- Barlett CP, Fennel M. Examining the relation between parental ignorance and youths’ cyberbullying perpetration. Psychol Pop Media Cult. 2018;7(4):547-560. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000139 ↵

- Mesch GS. Parental mediation, online activities, and cyberbullying. http://www.liebertpub.com/cpb. 2009;12(4):387-393. https://doi.org/10.1089/CPB.2009.0068 ↵

- Vale A, Pereira F, Gonçalves M, Matos M. Cyber-aggression in adolescence and internet parenting styles: A study with victims, perpetrators and victim-perpetrators. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2018;93:88-99. ↵

- Anderson M, Jiang J. Teens, Social Media & Technology 2018. Pew Research Center; 2018. https://search.informit.org/documentSummary ↵

- Helfrich EL, Doty JL, Su YW, Yourell JL, Gabrielli J. Parental views on preventing and minimizing negative effects of cyberbullying. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;118:105377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105377 ↵

- Meter DJ, Bauman S. Moral Disengagement About cyberbullying and parental monitoring: Effects on traditional bullying and victimization via cyberbullying involvement. J Early Adolesc. 2018;38(3):303-326. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431616670752 ↵

- Hessel H, He Y, Dworkin J. Paternal monitoring: The relationship between online and in-person solicitation and youth outcomes. J Youth Adolesc 2016 462. 2016;46(2):288-299. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10964-016-0490-6 ↵

- Wisniewski P, Carroll JM, Rosson MB. Grand challenges of researching adolescent online safety: A family systems approach. In: Association for Information Systems Conference Proceedings; 2013. ↵

- Padilla-Walker LM, Coyne SM, Collier KM. Longitudinal relations between parental media monitoring and adolescent aggression, prosocial behavior, and externalizing problems. J Adolesc. 2016;46:86-97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.11.002 ↵

- Helfrich EL, Doty JL, Su YW, Yourell JL, Gabrielli J. Parental views on preventing and minimizing negative effects of cyberbullying. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;118:105377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105377 ↵

- Cassidy W, Brown K, Jackson M. “Making kind cool”: Parents’ suggestions for preventing cyber bullying and fostering cyber kindness. J Educ Comput Res. 2012;46(4):415-436. ↵

- Erickson LB, Wisniewski P, Xu H, Carroll JM, Rosson MB, Perkins DF. The boundaries between: Parental involvement in a teen’s online world. J Assoc Inf Sci Technol. 2016;67(6):1384-1403. https://doi.org/10.1002/ASI.23450 ↵

- Erickson LB, Wisniewski P, Xu H, Carroll JM, Rosson MB, Perkins DF. The boundaries between: Parental involvement in a teen’s online world. J Assoc Inf Sci Technol. 2016;67(6):1384-1403. https://doi.org/10.1002/ASI.23450 ↵

- Padilla-Walker LM, Stockdale LA, Son D, Coyne SM, Stinnett SC. Associations between parental media monitoring style, information management, and prosocial and aggressive behaviors. J Soc Pers Relat. 2020;37(1):180-200. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407519859653 ↵

- Baumgartner SE, Valkenburg PM, Peter J. Assessing causality in the relationship between adolescents’ risky sexual online behavior and their perceptions of this behavior. J Youth Adolesc 2010 3910. 2010;39(10):1226-1239. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10964-010-9512-Y ↵

- Sasson H, Mesch G. Parental mediation, peer norms and risky online behavior among adolescents. Comput Human Behav. 2014;33:32-38. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CHB.2013.12.025 ↵

- Gabrielli J, Tanski SE. The A, B, Cs of youth technology access: Promoting effective media parenting. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2020;59(4-5):496-499. https://doi.org/10.1177/0009922819901008 ↵

- Wisniewski P, Carroll JM, Rosson MB. Grand challenges of researching adolescent online safety: A family systems approach. In: Association for Information Systems Conference Proceedings; 2013. ↵

- Helfrich EL, Doty JL, Su YW, Yourell JL, Gabrielli J. Parental views on preventing and minimizing negative effects of cyberbullying. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;118:105377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105377 ↵

- Cassidy W, Brown K, Jackson M. “Making kind cool”: Parents’ suggestions for preventing cyber bullying and fostering cyber kindness. J Educ Comput Res. 2012;46(4):415-436. ↵

- Rahayu NW, Haningsih S. Digital parenting competence of mother as informal educator is not inline with internet access. Int J Child-Computer Interact. 2021;29:100291. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJCCI.2021.100291 ↵

- Mehari KR, Doty JL, Sharma D, Wisniewski PJ, Moreno MA, Sharmafari N. Stability of Cyberbullying Rates among U.S. and Indian Adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal study. Under Review. ↵

- Navarro R. Gender issues and cyberbullying in children and adolescents: From gender differences to gender identity measures. Cyberbullying Across Globe Gender, Fam Ment Heal. Published online January 1, 2016:35-61. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-25552-1_2 ↵

- Doty J, Dworkin J, Review JC-FS, 2012 undefined. Examining digital differences: Parents’ online activities. scholar.archive.org. 2012;17(2). Accessed October 13, 2021. https://scholar.archive.org/work/yyqzyrtfybe3llhqmwmzylu36u/access/wayback/http://familyscienceassociation.org:80/sites/default/files/2- Doty_Dworkin_Connell.pdf ↵

- Elsaesser C, Russell B, Ohannessian CMC, Patton D. Parenting in a digital age: A review of parents’ role in preventing adolescent cyberbullying. Aggress Violent Behav. 2017;35:62-72. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AVB.2017.06.004 ↵

- Kang KI, Kang K, Kim C. Risk factors influencing cyberbullying perpetration among middle school students in Korea: Analysis using the zero-inflated negative binomial regression model. Int J Environ Res Public Heal 2021, Vol 18, Page 2224. 2021;18(5):2224. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052224 ↵

- Vazsonyi AT, Ksinan Jiskrova G, Özdemir Y, Bell MM. Bullying and cyberbullying in Turkish adolescents: Direct and indirect effects of parenting processes. J Cross Cult Psychol. 2017;48(8):1153-1171. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022116687853 ↵

- Vaterlaus JM, Beckert TE, Schmitt-Wilson S. Parent–child time together: The role of interactive technology with adolescent and young adult children: J. Fam Issues. 2019;40(15):2179-2202. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X19856644 ↵

- Cerna A, Machackova H, Dedkova L. Whom to trust: The role of mediation and perceived harm in support seeking by cyberbullying victims. Child Soc. 2016;30(4):265-277. https://doi.org/10.1111/CHSO.12136 ↵

- Dishion TJ, Stormshak EA, Kavanagh KA. Everyday Parenting: A Professional’s Guide to Building Family Management Skills. Research Press.; 2012. Accessed October 13, 2021. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2011-23787-000 ↵

- Milkie MA, Wray D, Boeckmann I. Creating versus negating togetherness: Perceptual and emotional differences in parent-teenager reported time. J Marriage Fam. 2021;83(4):1154-1175. https://doi.org/10.1111/JOMF.12764 ↵

- Newland LA, Coyl-Shepherd DD, Paquette D. Implications of mothering and fathering for children’s development. Early Child Dev Care. 2013;183(3-4):337-342. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2012.711586 ↵

- Newland LA, Lawler MJ, Giger JT, Roh S, Carr ER. Predictors of children’s subjective well-being in rural communities of the United States. Child Indic Res. 2015;8(1):177-198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-014-9287-x ↵

- Moreno MA, Kerr BR, Jenkins M, Lam E, Malik FS. Perspectives on smartphone ownership and use by early adolescents. J Adolesc Heal. 2019;64(4):437-442. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JADOHEALTH.2018.08.017 ↵

- Gabrielli J, Tanski SE. The A, B, Cs of youth technology access: Promoting effective media parenting. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2020;59(4-5):496-499. https://doi.org/10.1177/0009922819901008 ↵

- Breen G. Kindness Wins : A Simple, No Nonsense Guide to Teaching Our Kids How to Be Kind Online. Book Trope Editions. ↵

- Gabrielli J, Marsch L, Tanski S. TECH parenting to promote effective media management. Pediatrics. 2018;142(1):e20173718. ↵

- Gabrielli J, Marsch L, Tanski S. TECH parenting to promote effective media management. Pediatrics. 2018;142(1):e20173718. ↵

- Gabrielli J, Marsch L, Tanski S. TECH parenting to promote effective media management. Pediatrics. 2018;142(1):e20173718. ↵

- Gabrielli J, Tanski SE. The A, B, Cs of youth technology access: Promoting effective media parenting. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2020;59(4-5):496-499. https://doi.org/10.1177/0009922819901008 ↵

- Baxter LA, Bylund CL, Imes R, Routsong T. Parent-child perceptions of parental behavioral control through rule-setting for risky health choices during adolescence. J Fam Commun. 2009;9(4):251-271. https://doi.org/10.1080/15267430903255920 ↵

- Rodríguez-de-Dios I, van Oosten JMF, Igartua JJ. A study of the relationship between parental mediation and adolescents’ digital skills, online risks and online opportunities. Comput Human Behav. 2018;82:186-198. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CHB.2018.01.012 ↵

- Khurana A, Bleakley A, Jordan AB, Romer D. The protective effects of parental monitoring and internet restriction on adolescents’ risk of online harassment. J Youth Adolesc. 2015;44(5):1039-1047. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-014-0242-4 ↵

- Dishion TJ, Stormshak EA, Kavanagh KA. Everyday Parenting: A Professional’s Guide to Building Family Management Skills. Research Press.; 2012. Accessed October 13, 2021. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2011-23787-000 ↵

- Dishion TJ, Stormshak EA, Kavanagh KA. Everyday Parenting: A Professional’s Guide to Building Family Management Skills. Research Press.; 2012. Accessed October 13, 2021. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2011-23787-000 ↵

- Wisniewski P, Ghosh AK, Xu H, Rosson MB, Carroll JM. Parental control vs. teen self-regulation: Is there a middle ground for mobile online safety? Proc 2017 ACM Conf Comput Support Coop Work Soc Comput. Published online 2017. https://doi.org/10.1145/2998181 ↵

- Ttofi MM, Farrington DP. Effectiveness of school-based programs to reduce bullying: A systematic and meta-analytic review. J Exp Criminol. 2011;7(1):27-56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-010-9109-1 ↵

- Sondhi R. Parenting adolescents in India: A cultural perspective. In: Child and Adolescent Mental Health. InTech; 2017. https://doi.org/10.5772/66451 ↵

- Kang KI, Kang K, Kim C. Risk factors influencing cyberbullying perpetration among middle school students in Korea: Analysis using the zero-inflated negative binomial regression model. Int J Environ Res Public Heal 2021, Vol 18, Page 2224. 2021;18(5):2224. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052224 ↵

- Vazsonyi AT, Ksinan Jiskrova G, Özdemir Y, Bell MM. Bullying and cyberbullying in Turkish adolescents: Direct and indirect effects of parenting processes. J Cross Cult Psychol. 2017;48(8):1153-1171. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022116687853 ↵

- Sondhi R. Parenting adolescents in India: A cultural perspective. In: Child and Adolescent Mental Health. InTech; 2017. https://doi.org/10.5772/66451 ↵

- Wong TKY, Konishi C. The interplay of perceived parenting practices and bullying victimization among Hong Kong adolescents. J Soc Pers Relat. Published online November 10, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407520969907 ↵

- Meter DJ, Bauman S. Moral Disengagement About cyberbullying and parental monitoring: Effects on traditional bullying and victimization via cyberbullying involvement. J Early Adolesc. 2018;38(3):303-326. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431616670752 ↵

- Doty JL, Girón K, Mehari RK, et al. The dosage, context, and modality of interventions to prevent cyberbullying perpetration and victimization: A systematic review. Prev Sci. In press. ↵

- Moreno MA, Binger KS, Zhao Q, Eickhoff JC. Effect of a family media use plan on media rule engagement among adolescents: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(4):351-358. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMAPEDIATRICS.2020.5629 ↵

- Cassidy W, Brown K, Jackson M. “Making kind cool”: Parents’ suggestions for preventing cyber bullying and fostering cyber kindness. J Educ Comput Res. 2012;46(4):415-436. ↵