Module 4: The Case of the Spay-Neuter Skeptic

Trap-Neuter-Return Programs

Managing community cats by Trap-Neuter-Return (TNR) and Return-to-Field (RTF) are similar in that healthy cats that are thriving in their neighborhoods are captured, sterilized, vaccinated, and returned to the original location. The unique difference is that TNR is carried out in the community whereas RTF involves cats brought to the shelter.

Traditional Trap-Neuter-Return Programs

Traditional TNR programs, such as Operation Catnip at the University of Florida, encourage caregivers to trap community cats, which are then sterilized, vaccinated, ear-tipped, and returned to their outdoor homes. These programs are generally carried out without the need for shelter services.

Return–to–Field Programs

Building upon the success of traditional TNR programs, many shelters have implemented Return-to-Field (RTF) programs as well. RTF is similar to TNR, except that it is applied to free-roaming cats that have been admitted to the shelter. Good body condition of free-roaming is taken as evidence that the cats have an adequate source of food and are thriving in their neighborhoods. Many of these cats have one or more neighborhood feeders, but their identity may not be known to the shelter. In RTF, healthy unowned cats in good condition are sterilized, vaccinated, and returned to the location of origin as an alternative to euthanasia, even if their source of food is unknown.

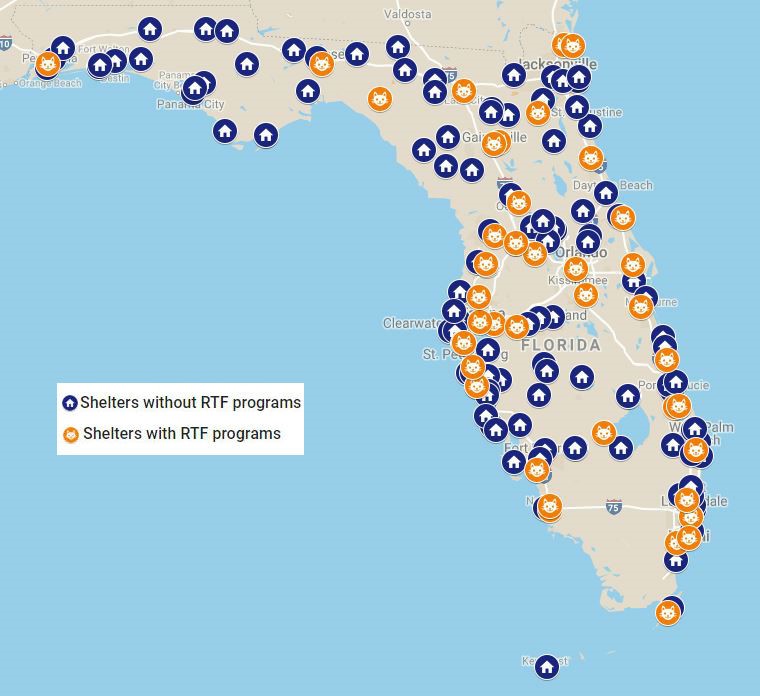

In addition to reducing the dependency on euthanasia for managing the number of cats in shelters, RTF facilitates the reunification of outdoor cats with their owners. Some free-roaming cats are outdoor pets who are mistakenly “rescued” and brought to the shelter by Good Samaritans. However, being taken to a shelter may actually reduce a pet cat’s chances of being reunited with its family. Less than 2% of cats brought to shelters are returned to their owners (compared to 20% or more of dogs). Most missing cats are found within a few blocks of their home, and “returning home on their own” is the most common way cats are reunited. In fact, lost cats are 13 times more likely to find their way home on their own than they are to be reunited with their owners through the shelter. That means that RTF not only saves community cats, but it saves lost pet cats as well. The successful track record of RTF programs has led to their rapid expansion across the country.

Trap-Neuter-Return Impact on Shelter Lifesaving and Community Cat Populations

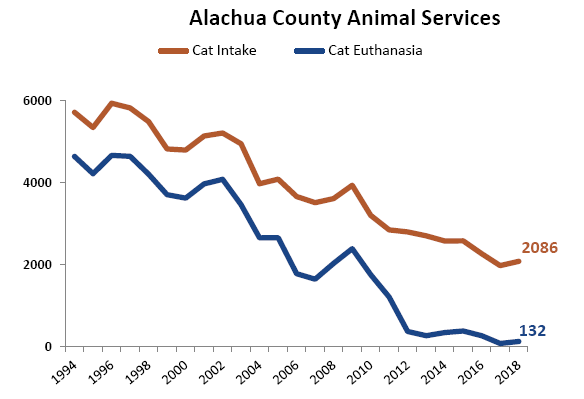

In Alachua County, Operation Catnip’s traditional TNR program contributed to a decrease in the euthanasia of cats at the local shelter from 81% to 42% in 13 years. When RTF was added to return stray shelter cats to their neighborhoods, the euthanasia rate fell even further, to 8% in 2018.

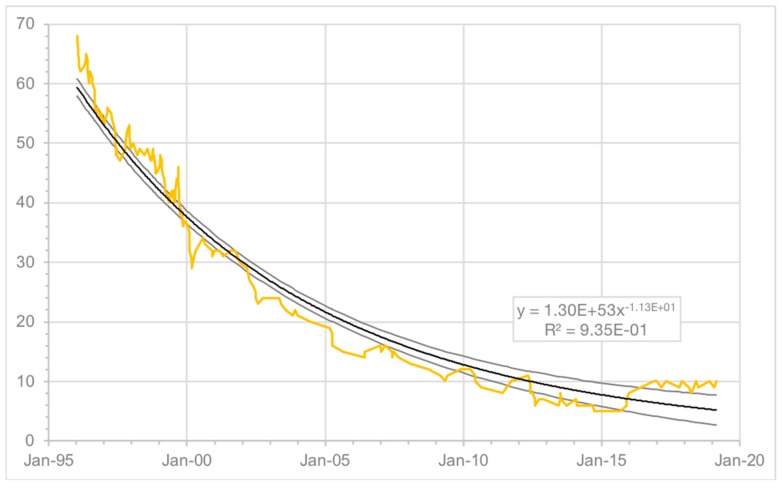

One of the most immediate impacts of TNR programs is a reduction in the number of kittens born in the field, a population that suffers 50%-75% mortality. As a result of the high feline reproductive capacity, kitten deaths usually comprise a large majority of overall mortalities that can be influenced by management actions or inactions. However, TNR must be performed in high enough numbers over the shortest amount of time to achieve the most benefit. With sufficient intensity, TNR offers significant advantages in terms of minimizing preventable deaths, while also substantially reducing population size. High-intensity TNR programs can be further improved by reducing abandonment, or by combining return-to-field for some cats with adoption for others. On the other hand, at lower sterilization intensities the longer-term lifesaving advantages of TNR become much less compelling because large numbers of kittens remain subjected to high mortality rates over time. But, comprehensive TNR programs are not just about saving cats and reducing shelter intake. They also improve neighborhoods, promote public health, and mitigate impacts on wildlife by reducing the number of cats in the environment over time.