OLD SECTIONS

28 Inclusive Teaching (Move)

Jeremy Waisome, Ph.D. and Alexandra Bitton-Bailey

What is an Inclusive Environment? | Humanizing Your Course | References

What is an Inclusive Environment?

- Freely express who they are, their opinions, and their point of view

- Fully participate in learning, teamwork, and all classroom activities

- Feel safe from abuse, harassment, or unfair criticism

- Feel valued and supported by their instructor and classmates

How can you create a friendly and welcoming learning environment that challenges and motivates students to learn and grow? Inclusive language paired with in-class actions that demonstrate your support and acceptance of diverse backgrounds and skills.

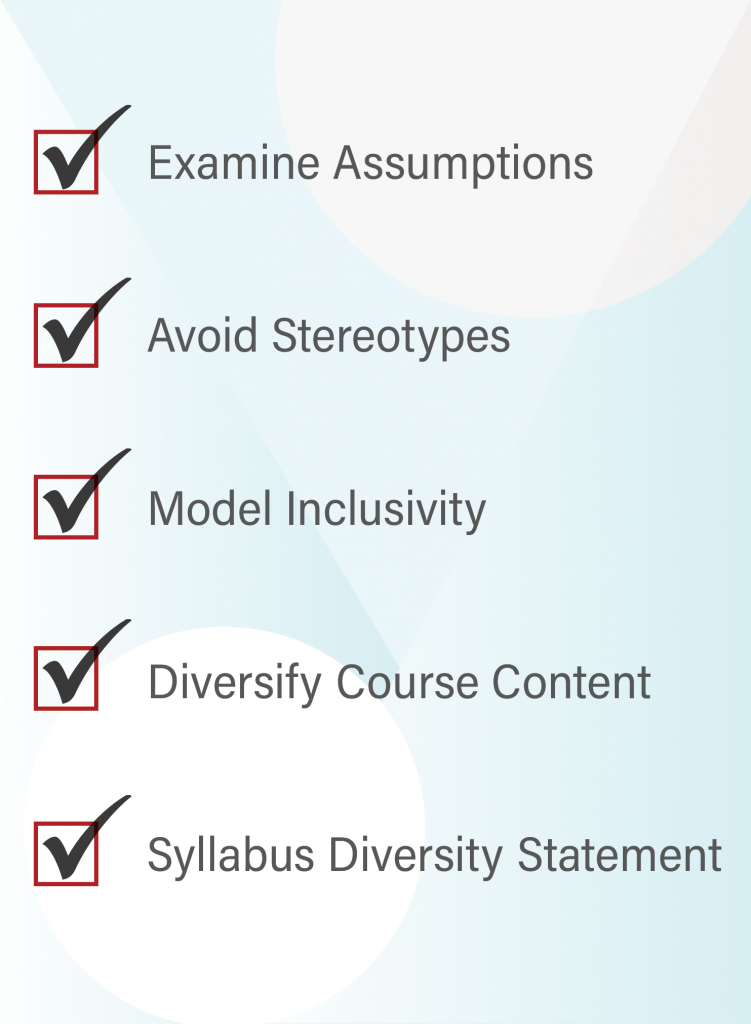

Examine Your Assumptions

- We all have biases!

- Become aware of your assumptions and work towards replacing them

- Not everyone attending your course has similar backgrounds

- Avoid assuming student performance is evidence of “natural” ability

Avoid Stereotypes

- Stereotypes are: an often unfair and untrue belief that many people have about all people or things with a particular characteristic

- You must learn to separate individuals from stereotypes

Model Inclusivity

- Use inclusive language

- Consider using preferred names/pronouns

- Try not to use terms like “guys”

- Model inclusive behavior

- Ask for multiple responses to a question posed in class

- Show that mistakes and missteps are valued as opportunities for learning

Diversify Course Content/Activities

- Use diverse examples

- Change the names, identities, or ability of the persons used in your examples/case studies

- Highlight contributions of scholars from underrepresented groups in your field

- Be mindful when selecting groups

Writing a Syllabus Diversity Statement

A diversity statement should express your core values of inclusion.

A good place to begin is by examining your assumptions. It is common for people to make assumptions, often subconsciously, that may lead to the marginalization of students in our classrooms. This is called implicit bias. Expectations that students share similar cultural backgrounds, economic circumstances, come from traditional families, have parents who attended college, or are heterosexual or cisgender, can make students feel marginalized. It is important to develop an awareness of these biases and to replace them with inclusive language and behavior.

Example Diversity Syllabus Statements were borrowed from the American Society for Engineering Educations Committee on Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion.

Example 1:

I consider this classroom to be a place where you will be treated with respect, and I welcome individuals of all ages, backgrounds, beliefs, ethnicities, genders, gender identities, gender expressions, national origins, religious affiliations, sexual orientations, ability – and other visible and nonvisible differences. All members of this class are expected to contribute to a respectful, welcoming and inclusive environment for every other member of the class.

Example 2:

I am committed to creating an inclusive environment in which all students are respected and valued. I will not tolerate disrespectful language or behavior on the basis of age, ability, color/ethnicity/race, gender identity/expression, marital/parental status, military/veteran’s status, national origin, political affiliation, religious/spiritual beliefs, sex, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status or other visible or non-visible differences.

Other Statements to Foster Inclusivity:

- Safe Zone Statement for LGBTQ+ Advocacy in STEM

- Preferred Name/Pronoun Statement

Additional Resources:

- Inside Higher Ed Article-Breaking Down Diversity Statements

- Inside Higher Ed Article-The Effective Diversity Statement

- Yale Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning-Diversity Statements

- Brown Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning-Diversity & Inclusion Syllabus Statements

Humanizing Your Course

What Does Humanizing Your Course Mean?

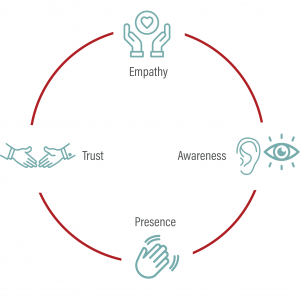

Humanizing is a student-centered mindset that involves recognizing and supporting the non-cognitive components of learning. Humanizing integrates elements of Culturally Responsive Teaching and Learning and Universal Design for Learning. In a humanized course, faculty intentionally cultivate an inclusive learning environment that fosters psychological safety and trust and forms connections that grow into relationships and a community. With an emphasis on presence, empathy, and awareness, faculty become warm demanders and students apply themselves at a higher level to not let down their learning partner.

Humanizing is a student-centered mindset that involves recognizing and supporting the non-cognitive components of learning. Humanizing integrates elements of Culturally Responsive Teaching and Learning and Universal Design for Learning. In a humanized course, faculty intentionally cultivate an inclusive learning environment that fosters psychological safety and trust and forms connections that grow into relationships and a community. With an emphasis on presence, empathy, and awareness, faculty become warm demanders and students apply themselves at a higher level to not let down their learning partner.

Why Do It?

Online courses increase access to higher education for students who have been traditionally left out. However, this increased access does not translate into success. Minority and first generation students are less likely to succeed in online courses, particularly courses that lack humanized elements. Adding the humanized touches to your course can increase both retention and success of all students.

Students and Faculty Benefit

Students benefit as it promotes trust in their instructor. In fact, studies show the most valued characteristics in instructors is not their expertise in their field but rather it is the ability to demonstrate caring for their students. Students also gain greater positive regard for faculty who practice Humanized courses. Instructors with humanized courses also see a marked increase in students’ perceptions of their ability to successfully complete courses. Humanized courses provide students with the ability to develop and practice soft skills and increase opportunities for professional and peer to per exchanges.

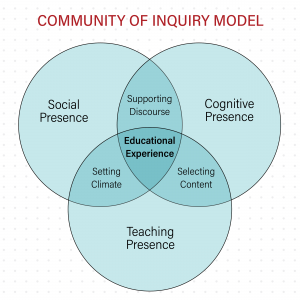

Community of Inquiry

Community of Inquiry Model

The Community of Inquiry (COI) model is an educational framework that was first developed by a team of Canadian Social Scientists in the late 90’s. According to this model, a “community” is formed by the students plus the instructor–and both roles are important for success of the learner. The authors of this theoretical framework identify three overlapping, essential aspects of an educational environment that, collectively, optimize learning. These are the cognitive presence, the teaching presence, and the social presence. When these aspects of a learning environment are attended to and balanced, the result can be a meaningful educational experience for everyone in the learning community.

Overlapping Elements of the COI Model

The cognitive presence in an educational setting reflects the degree to which community members can learn through constructive, productive discourse about the course content. In other words, the role of communication and engagement in developing deep understanding and applicable ideas. Certainly, this cannot be done well in isolation from other students or without guidance from an involved instructor. The social presence can be described as the ability of learners to bring their “true” selves to the learning environment.

When students are given the opportunity to express themselves within various aspects of a learning environment, they become more personally invested in the relationships they build with classmates and the instructor–and this facilitates a trusting community where students want to engage and learn. For this to work at its best, students must feel comfortable/safe to share their stories and instructors play a critical role in providing guidelines, structure, and feedback for this to occur. The teaching presence, then, is the role of the instructor in selecting excellent content and designing a course/learning environment (assignments, discussion boards, syllabus, assessments, etc.) that marries the cognitive and social presences so that learning outcomes are met.

While the cognitive and social elements play out during the course, the teaching presence is important before, during, and after the course (Fiok, 2020).

Humanized Teaching

Humanized online courses work to support the non-cognitive components of learning. They support the student as a whole and take into consideration the value and significance of emotion to deep learning. Humanized courses also create a culture of possibility for students. where many courses, whether they are weed-out courses or not, feel as though they are to students.

The paradigm shifts in humanized courses to “I think or I know I can do it” for students.

The general feel for students is that they do not think they can be successful. The paradigm shifts in humanized courses to “I think or I know I can do it” for students. Humanized courses also value the diverse talents and perspectives students bring to the class. Instructors in humanized courses find ways to help students share their story and knowledge and use them to create a richer community of learning. Humanized courses are characterized by a sense of community that frames the whole course. This community provides students with a sense of belonging that supports

Principles of Humanized Courses

Social Presence

“Social presence is the extent to which persons are perceived to be real and are able to be authentically known and connected to others in mediated communications” (Bentley, Secret, & Cummings, 2015).

At the core of social presence are interpersonal interactions between the instructor and students. The interpersonal interactions have a critical role to play in student learning. Quality interactions help to reduce transactional distance and strengthen students’ connection to the course. These interactions are what allow us as instructors to create social presence in our courses and to show our students that we care. Studies have shown that from the students perspective, the single most important factor determining the quality of an online course or instructor is the instructor’s presence and caring.

Relationship

Interpersonal interactions among students also contribute to student success and learning. In fact, relationships are key to supporting the success of more students. Relationships start with psychological safety and creating psychological safety requires us to take off our armor and be vulnerable. For students to feel comfortable building relations in the course, we as instructors have to create a learning community for students. Carefully crafted collaborative work “encourages critical thinking, problem solving, analysis, integration, and synthesis; provides cognitive supports to learners; and ultimately promotes a deeper understanding of the material” (Jaggars & Xu, 2016)

Empathy and Awareness

Integrate culturally responsive teaching and learning. The first step in culturally responsive teaching is looking within ourselves as instructors. We can take an inventory of the attitudes and beliefs that impact how we relate and interact with others, specifically with our students. Harvard University’s Project Implicit has an online test that can help us take a reflective look at our own implicit (unintentional and unconscious) biases.

Culturally responsive teaching also requires that we be aware of the sociopolitical context our students and schools are operating under. Helping students to understand the systems working around them is key. Giving context to the situation and being willing to tackle difficult conversations is invaluable. A great resource for this is the video Affirming Diversity by Sonia Nieto.

Exploring our teaching practice and setting goals for practicing inclusive culturally responsive teaching requires that we marry empathy, compassion to our high expectations for our students. Helping students become co-creators of their learning experience and learning environment gives students ownership and agency in their own learning. Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles also contribute to creating a class that is inclusive and humanized. UDL principles help us to take into consideration and diminish any barriers to learning that exist in our classes. To learn more about implementing UDL into your class, visit the CTE resource library.

Strategies

Be Approachable

Humanizing your course does not have to be overwhelming. Start small and make yourself approachable. Many students are intimidated by instructors and do not feel like they can come to office hours or send questions. This is particularly true for some international students. One easy way to make yourself approachable is to have students sign up for a 5-10 time slot during your office hours at the beginning of the semester. Use that time to get to know your students. Once your students have met with you at least once they will be more likely to come to office hours and ask their questions. Synchronous online office hours can help foster interpersonal relationships with and among students.

Tone and Personality

To start the semester on a positive note be sure to use a tone that reflects you and your personality. Set the tone by making friendly (and appropriate) jokes, using comedic salutations, including emoticons that can translate feelings and emotions to your short messages and soften the tone. Read over your syllabus, announcements, and assignments to check not only for accuracy but for tone and personality. Do your communications sound friendly and inviting? Keep it genuine and “authentically you” without trying to sound cool. Digital Postcards can help you establish a friendly and open tone to the class. Create a video postcard in place of a written weekly announcement. Use your phone to make an on-the-go video that shows students a little bit of your life. Check out a few great examples of video postcards.

Get to Know Your Students

Getting to know your students will allow you to also get a sense of when students need extra help. When individual students face challenging times you can reach out to them and connect them with university resources that might help them. There are times that are universally challenging such as national disasters, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the current social justice movement. In times such as these sending encouraging video messages to all students can make your presence a comfort to your students.

Communicate Their Way

It can be a little challenging and daunting to open up your email first thing in the morning and see a long list of student emails that need immediate answers. Many questions students ask might only require a very quick response of a few words. The accumulation of several dozen of these can cause mild panic. Students also prefer other means of communicating with each other and their instructors, methods that better reflect how they communicate with others in “real life.” Using a Google Voice number gives students the ability to text you without having your personal contact information. You can answer quick questions on the fly. You can also use other apps that help encourage a learning community to develop such as Group Me, Twitter, and Teams.

Build in Ground Rules and Flexibility

A class activity to establish ground rules can give students a sense of ownership of the course, help them remain accountable, and provide a sense of safety and inclusion (see Guidelines for Discussing Difficult or High Stakes Topics). Place students in small groups and have them develop a set of course ground rules. You can suggest topics they should think about such as good discussions and feedback, late assignments, difficult or controversial topics. Collect and synthesize as a whole class the rules into a small set that the entire class agrees on. Students will have greater buy in and help keep each other accountable throughout the course.

Build Community

1. Icebreakers

To get started on the right foot, plan an icebreaker activity that will give your students a chance to get to know each and begin building a sense of community and connection. This is especially important in online courses and courses that include collaborative or group work. Icebreakers can also help orient students to the class and syllabus. We have included a full list of icebreakers you can implement easily with directions for you to explore and choose from.

To get started on the right foot, plan an icebreaker activity that will give your students a chance to get to know each and begin building a sense of community and connection. This is especially important in online courses and courses that include collaborative or group work. Icebreakers can also help orient students to the class and syllabus. We have included a full list of icebreakers you can implement easily with directions for you to explore and choose from.

2. Isn’t that Cool

To encourage ongoing quality and scholarly interaction you can add an “Isn’t That Cool Discussion Board.” It can be a place where you allow students to post things they discover relating to the course in their everyday lives. Videos they watched, articles they read, pictures of things they saw that are cool and that they want to share with others. This helps to continue the conversational tone of the class throughout the semester.

To encourage ongoing quality and scholarly interaction you can add an “Isn’t That Cool Discussion Board.” It can be a place where you allow students to post things they discover relating to the course in their everyday lives. Videos they watched, articles they read, pictures of things they saw that are cool and that they want to share with others. This helps to continue the conversational tone of the class throughout the semester.

3. Sharing is Caring

Finally, for the benefit of all students you can add a “Sharing is Caring Discussion Board.” A discussion board where students are able to share notes they have taken during lectures and labs. This encourages great note taking and develops a rich resource for the whole class to share. An additional benefit is that it may help students who would normally need a note taking accommodation by meeting that need before students even have to make the request. Best of all it helps all students because we all miss something once in a while.

Finally, for the benefit of all students you can add a “Sharing is Caring Discussion Board.” A discussion board where students are able to share notes they have taken during lectures and labs. This encourages great note taking and develops a rich resource for the whole class to share. An additional benefit is that it may help students who would normally need a note taking accommodation by meeting that need before students even have to make the request. Best of all it helps all students because we all miss something once in a while.

4. Celebrate

In the business of the semester it is easy to forget to celebrate milestones and victories big and small. Celebrate regularly, make a big deal of exam successes, great papers, groups that went above and beyond. If you’re up for it add in some personal victories like birthdays, new jobs, awards and other life accomplishments. Celebrating accomplishments and sharing in these personal victories, especially in online courses helps to combat feelings of isolation and builds great connections and relationships.

In the business of the semester it is easy to forget to celebrate milestones and victories big and small. Celebrate regularly, make a big deal of exam successes, great papers, groups that went above and beyond. If you’re up for it add in some personal victories like birthdays, new jobs, awards and other life accomplishments. Celebrating accomplishments and sharing in these personal victories, especially in online courses helps to combat feelings of isolation and builds great connections and relationships.

Workshop Recordings

Humanized learning increases the relevance of content and improves students’ motivation. Students can see themselves as part of a larger community with instructors who foster connections. This workshop explores strategies to improve awareness, empathy, and presence while sharing specific techniques, activities, and course designs ideas that can help to humanize any course.

Alexandra Bitton-Bailey: Humanizing Your Course (1:47:51)

References

- Stephens, G. J., Silbert, L. J., Hasson, U. (2010). Speaker-listener neural coupling underlies successful communication. PNAS Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107(32), 14425-14430.

- Hammond, Z. L. (2014). Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain: Promoting Authentic Engagement and Rigor Among Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Students. Corwin Publishers.

- Estrada, M., Burnett, M., Campbell, A. G., Campbell, P. B., Denetclaw, W. F., Gutiérrez, C. G., … Zavala, M. (2016). Improving underrepresented minority student persistence in STEM. CBE Life Sciences Education, 15(3). doi:10.1187/cbe.16-01-0038

- Fiock, H. (2020). Designing a Community of Inquiry in Online Courses. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 21(1), 134-152. doi:10.19173/irrodl.v20i5.3985

- James, S., Swan, K., Daston, C. (2015). Retention, progression and the taking of online courses. Online Learning, 20(2). Retrieved from https://olj.onlinelearningconsortium.org/index.php/olj/article/view/780.

- Jaggars, S. S. & Xu, D. (2016) How do Online Course Design Features Influence Student Performance? Computers & Education, 95.

- (2015) The Centrality of Social Presence in Online Teaching and Learning in Social Work, Journal of Social Work Education, 51:3, 494-504, DOI: 10.1080/10437797.2015.1043199

- Rucker, N. (2019, December 10). Getting Started With Culturally Responsive Teaching. Retrieved July 31, 2020, from https://www.edutopia.org/article/getting-started-culturally-responsive-teaching