Learning Activities

21 Active Learning Online

Alexandra Bitton-Bailey

What is Active Learning? | Does Active Learning Work? | How Does it Work in an Online Course? | Reinforce Learning: Remember and Understand | Collaborative Learning | 11 Quick Tips for Collaborative Learning | Helpful Resources | References

What is Active Learning?

Active learning is “anything that involves students in doing things and thinking about the things they are doing” (Bonwell & Eison, 1991, p. 2). Active and problem-based learning involves and engages students with the resources and activities by requiring them to participate in learning actively, instead of passively sitting and listening or watching.

Does Active Learning Work?

Overwhelming evidence confirms that students learn more effectively through active learning than in a traditional lecture, or “teacher telling” format. Freeman and colleagues conducted a meta-analysis of more than 225 studies on the impact and efficacy of active learning comparing “constructivist versus exposition-centered designs in STEM courses (Freeman et al., 2014; Prince, 2013) and the results showed that students in traditional lecture courses were 1.5 times more likely to fail than students in active learning courses.

How Does it Work in an Online Course?

In many cases, we can think of quick easy ways to implement short active learning components in a face to face course. But when thinking about an online course, especially a course that quickly transitioned to online, things can seem a little more challenging, daunting even. But it does not have to be. Take watching a video, for example. Pairing a video with guided notes is a simple way to incorporate an active learning strategy that can help students with the lower levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy such as “remember” and “understand.”

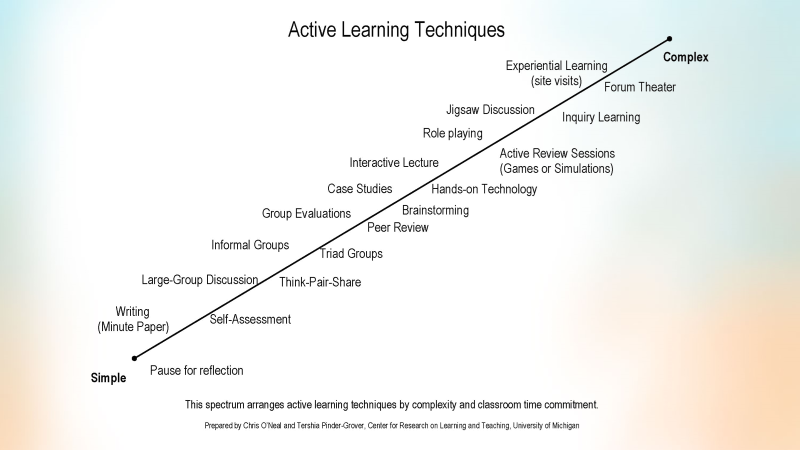

Active Learning Continuum

Let’s consider the active learning continuum. The complexity of active learning techniques fall along a continuum, so there are active learning strategies that can be used at every level of Bloom’s Taxonomy.

Reinforce Learning: Remember and Understand

Before students can apply, analyze, evaluate, and create artifacts to reflect their mastery of concepts, they must have a solid grasp of foundational knowledge. They must remember and understand the important vocabulary, problems, functions, or formulas important to the course content.

Simple active learning strategies can help reinforce their grasp of this information. Here are some ideas for reinforcing learning:

Key Points Worksheets

Key points worksheets work well as a preparation activity. A simple preparation activity before class could involve studying content, answering questions on the worksheet, and taking a short quiz. Preparation content could involve a video, assigned texts, or a podcast. Next, they answer key questions on the worksheet about the course content. The students can then use the key points worksheet as a reference during class activities or a short quiz.

Guided or Collaborative Notes

There are several ways to help students actively take notes and share important information they glean from the lectures and videos.

An advanced organizer is a tool that can be created in Google or Canvas prior to a lecture to help students structure and organize the information they are about to learn.

3-2-1 technique can be created in a shared document or discussion board. Students can share 3 things they learned, 2 things they found interesting, and 1 thing they still have questions about. Leave an extra column for students to respond to each other’s remaining questions or if done in a discussion board have students try to answer the questions posed by their fellow students.

Cued Notes provide students with a structure to take better notes during a lecture through a template that cues students to take notes on important aspects of the lecture. Then have students summarize the whole lecture or video. You can also have students create the cues themselves, this is the Cornell note-taking method.

Collaborative notes or note-taking in pairs allow students to take and share notes on lectures and videos. In a large class, divide students into smaller groups or pairs, create a note-taking template or table, and have all members of the groups share their notes, takeaways, and perspectives in the table. This method helps students gain a more complete understanding, correct misconceptions, and gain different perspectives.

Card Sort or Mind Maps

Card sorts and mind maps help students to connect concepts and ideas. A card sort or mind map could be used as a formative assessment or activity focused on the information students read before class or to summarize what they learned in a lecture. Student groups could work together to use visual diagrams to show the connection of ideas or sort concepts from the readings into categories. Whether done synchronously or asynchronously online, these feel a little bit like a game to the students and encourage socializing, teamwork, and discussion. They can easily be done in breakout rooms, and there are a multitude of free tools available to easily build mind/concept maps.

Here are a few free and easy to use:

- Google Drawing (card sorting example-click “Make a Copy” to view the document)

- Coggle

- MindMapMaker

- FreeMind

- More information on concept maps, listen to this podcast from the University of Illinois or visit Using Concept Maps from Carnegie Mellon University.

Learning Reflections

Active Reading Documents (ARD) give students the necessary incentive to engage with the text/readings. ARDs work specifically on four levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy: retrieval, comprehension, analysis, and knowledge utilization.

First, students create a visual representation of the organizational structure of the key information. Next, they describe their understanding of the key information in their own words.

Then, students explain 3 original logical connections of information among or across categories within the course materials and 2 original connections across or among categories in other units of the course. Lastly, students uncover connections to other classes, subjects, or their personal lives.

Apply and Analyze Learning

Apply activities get students up and moving so they use their existing skills to develop new knowledge and demonstrate an ability to use the new skills and information. Possible activities include:

- Peer discussion

- Solve a problem

- Predict the outcome if. . .

- What can go wrong?

- Role-play

- Elicit curiosity with a question

Example: In Canvas, divide students into groups and provide each group with a discussion prompt such as, “predict how members of other cultures make decisions for the care of elderly relatives.” Assign each group a specific culture or better yet give them options and allow them to choose which cultural perspective they want to take.

Analyze activities get students immersed in real-world data and problems that reflect work they might do in their respective fields. These activities can include:

- Using real-world data whenever possible

- Have students participate in data collection

- Use current and relevant data

- Show the connection and value of the data

- Giving students their choice of problem when possible

- Students appreciate being given some choice

- Create groups with shared interests

- Give limited options or ask students to explain their choice in an initial assignment (scaffold)

- Dividing a large problem into smaller pieces

- Choose a problem

- Submit resources and research

- Provide a proposal or prospectus

- Include peer review

- Using mobile devices for in-class research

Example: In Canvas, divide students into groups and provide each group with an analysis prompt such as “critique a subway poster from various cultural perspectives.” Assign each group a specific demographic and have groups analyze the possible interpretations.

Collaborative Learning

For the upper learning levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy, you might opt for collaborative learning techniques. Collaborative learning techniques (CoLTs) require students to work together to explore significant questions or meaningful work that results in completing a project. In contrast to active learning techniques where an individual student can complete an entire exercise alone, CoLTs require at least some peer-to-peer interaction. These techniques have many benefits especially in courses that need to quickly transition to online.

- Encourage interaction

- Foster teamwork and interdependence

- Require students to work collaboratively on a product

- Develop group processing skills

- Offer opportunities for peer review and feedback

You can find details on how to implement some of our favorite (and easiest) collaborative learning techniques in Collaborative Learning Techniques: A Handbook for College Faculty (Barkley, Cross, & Major, 2014).

- Jigsaw

- Fishbowl

- Three-step interviews

- Think-pair-share

- Team anthologies

Best of all, each of these techniques can be done online!

11 Quick Tips for Collaborative Learning

For more details visit the collaborative learning chapter of this guide. Facilitating collaborative learning can be challenging. Here are some quick tips on how to create successful collaborative activities.

- Adapt existing activities to make them collaborative

- Start small

- Base the activity on a stated learning outcome

- Chunk the activity into bite-size pieces

- Have the activity reflect the work students will do as professionals

- Provide clear directions or a script

- Orient the groups to each other and the activity

- Minimize synchronous activities

- Give groups choices on how they collaborate

- Know your students

- Be flexible

Peer Review and Collaborative Learning

Peer review is a key part of collaborative learning. Peer review gives students the opportunity to learn an important skill: giving helpful feedback. It also allows students to receive more helpful feedback than from the instructor team alone. Keep these tips in mind when you introduce peer review to your students:

- Frame peer review as “helping to make work better”

- Allow ample time for peer review

- Provide a rubric and examples

- Give students a chance to practice

- Require a response to the peer feedback

- Get instructional design help if needed

For more information about the peer review process, visit Implementing Peer Review in Your Course from The Ohio State University or Peer Review: Intentional Design for Any Course Context from Columbia University.

Helpful Resources

Check out the Collaborative Learning Techniques: A Handbook for College Faculty book, which is available in full PDF in the Smathers Library. If you are off-campus, you must sign in using your Gatorlink account to access it.

- K. Patricia Cross Academy offers some great easy to adopt active learning techniques.

- Small Changes in Teaching: The First 5 Minutes of Class. (Chronicle of Higher Education, 2016)

- Discover how the Google suite of tools can foster active learning. Watch G-suite? Sweet! (41:07)

References

- Barkley, E. F., Major, C. H., & Cross, K. P. (2014). Collaborative learning techniques: A handbook for college faculty. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Chickering, A. W., & Gamson, Z. F. (1989). Seven principles for good practice in undergraduate education. Biochemical Education, 17(3), 140-141. doi:10.1016/0307-4412(89)90094-0

- Freeman, S., Eddy, S.L., McDonough, M., Smith, M.K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., and Wenderoth, M.P. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 111, 8410-8415.

- Haak, D. C., Hillerislambers, J., Pitre, E., & Freeman, S. (2011). Increased Structure and Active Learning Reduce the Achievement Gap in Introductory Biology. Science, 332(6034), 1213-1216. doi:10.1126/science.1204820

- Hake, R. R. (1998). Interactive-engagement versus traditional methods: A six-thousand-student survey of mechanics test data for introductory physics courses. American Journal of Physics, 66(1), 64-74. doi:10.1119/1.1880

- Lang, J. M. (2016). Small teaching: Everyday lessons from the science of learning. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Prince, M. (2004). Does Active Learning Work? A Review of the Research. Journal of Engineering Education, 93(3), 223-231. doi:10.1002/j.2168-9830.2004.tb00809.x